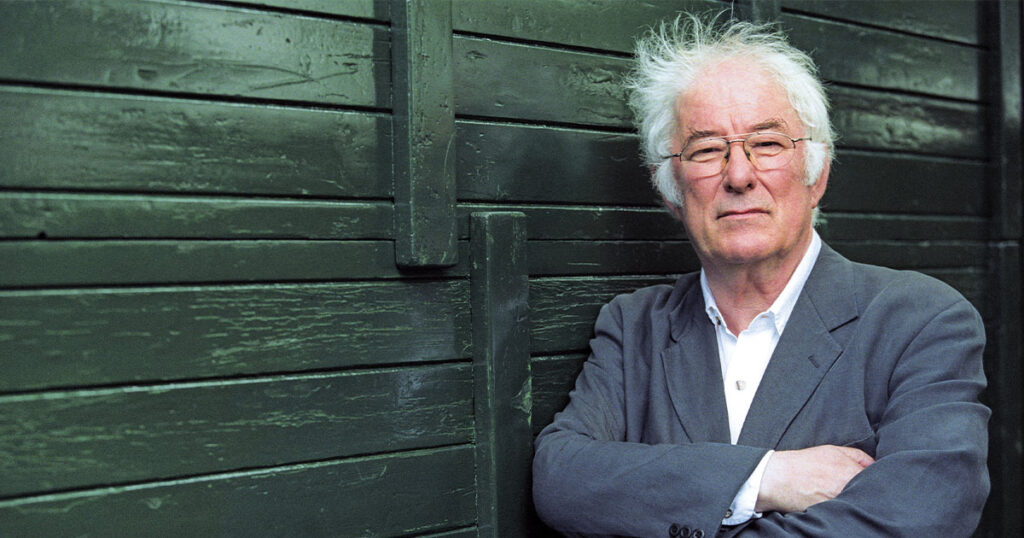

The Letters of Seamus Heaney selected and edited by Christopher Reid; Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 848 pp., $45

One St. Patrick’s Day in the early 1980s, I met Seamus Heaney for lunch at the Faculty Club at Harvard, where we were both teaching. The Boston area is one of the most proudly Irish places in America, and everybody was wearing green for the day. Everybody except Seamus Heaney, that is. Heaney was Irish to the core, but he had no patience for superficial symbolism. The challenge he faced was how to represent the essence of Irish culture to the world while brushing off the green-beer sentimentality we get a taste of every 17th of March.

Heaney would not have chosen to be a spokesman for Ireland, but he found himself thrust into that position by his fame. His newly published letters—800 pages of them, ably edited by Christopher Reid—are a study in how he tried to define himself while repeatedly contending with external pressures and a world that wanted to define him on its own terms. “You don’t have to make noises against the establishment if your name is Seamus,” he writes in an early letter discussing his politics, “it’s just taken for granted.” Heaney was not simply an Irish Catholic; he sprang from the Catholic minority in Northern Ireland, where the literary establishment greeted his work—and the emergence of a native Catholic, republican, rural voice—with hostility.

Michael Foley, co-editor of the Honest Ulsterman magazine, characterized Heaney’s verse as “everything that poetry should not be, a rejection of the urban world for pastoral nostalgia, a cautious upholding of all the Irish pieties (especially the Holy Trinity of nation, church and family).” Heaney’s wife, Marie, affectionately kidded him for being “the laureate of the root vegetable.” And having settled in the Republic of Ireland, he faced resentment from poets there who felt too much attention was being given to this interloper and to other Northern Irish writers such as the poet Derek Mahon and the playwright Brian Friel. After Bloody Sunday in 1972, when British soldiers shot 27 unarmed civilians during demonstrations in the Bogside neighborhood of Derry, Heaney became outspoken about the Troubles. His poem “The Other Side,” published the same year as Bloody Sunday, projects amicable coexistence between an Irish farming family and a Protestant neighbor. Heaney once told me that the poem was modeled after Robert Frost’s “Mending Wall.”

Self-assurance did not come naturally. When he published his first verses in the literary journal at Queen’s University, Belfast, he chose the pseudonym Incertus, Latin for “unsure of himself.” In one early letter, he jokingly calls himself a “cautious wee papist.” Yet on a deeper level, he had complete self-confidence, fortified by what he called “the Joycean/Yeatsian tradition in this country of regarding the word itself as somehow magical; turning the act of writing into an act of consecration where the bread and wine of daily life is consecrated into the host of language, the holy wafer of art.”

I lived in Ireland for a number of years and saw Heaney fairly often. One evening after a long, convivial, and boozy gathering at his home on Strand Road in Dublin, it was determined that someone had better give me a lift back to Trinity College, where I was teaching at the time. When Heaney came around with the car, it turned out to be a Mercedes sedan. I thought nothing of it, but Heaney sounded a little apologetic about the extravagance of the vehicle. In my experience, Irish people never like to be seen as putting on airs—it’s like in the American South, where “Don’t get above your raisin’ ” is a byword. His tongue-in-cheek explanation invoked a fellow poet: “Miłosz bought one, so I reckoned it was all right.”

Modesty and caution, a strict sense of obligation and a wariness about how he was seen by others—these were essential parts of who Heaney, the son of an Irish farming family, remained throughout his life. This fidelity to the values of the plain people of Ireland is something that sets him apart from the nation’s other Nobel laureate in poetry, William Butler Yeats, a visionary whose work is informed by a sense of grandeur and nobility. No poem of Heaney’s illustrates his down-to-earth values better than “The Haw Lantern,” in which he imagines the red berry of the hawthorn as “a small light for small people, / wanting no more from them but that they keep / the wick of self-respect from dying out, / not having to blind them with illumination.” These homely virtues endear him to Irish readers, who know him as one of their own. At Harvard, Heaney lived at Adams House, one of the residential halls. He would sometimes eat in the dining hall among the staff, kitchen workers, and janitors, many of them Irish American or recent immigrants from the old country. He enjoyed the familiarity of people whose ways and accents he would have been familiar with. No doubt he was homesick. The story goes that many of them knew him simply as Seamus, thought he was a fellow worker, having no idea they were in the company of a famous poet.

And yet, he also led the life of a literary celebrity. After his bibliographer, Rand Brandes, criticized his lifestyle, albeit mildly, Heaney responded: “Surely you, of all people, know from the inside that what appears as ‘stardom’ and ‘globetrotting’ is often simply the result of a decent sense of obligation.” But the strain was tremendous. In 2000, he wrote to his friend Dennis O’Driscoll: “Maybe it can be survived, but I’m not sure. The lookalike who goes to the platforms and the camera-calls has been robbed of much of himself.” He writes in another letter of a childhood spot on the Moyola River as “one of the few places where I am not haunted or hounded by the ‘mask’ of S.H.”

His sense of duty was a burden as much as a virtue. In a 1985 letter written from Adams House, he reports to a close friend, the painter Barrie Cooke,

In the last two days I have written thirty-two letters—none of them a real letter, of course, but all of them a weight that was lying on my mind even as the accursed envelopes lay week by week on my desk. The trouble is, I have about thirty-two more to write: I could ignore them but if I do the sense of worthlessness and hauntedness grows in me.

He had a large network of friends all over the world, and it was always a great event during the holiday season to see the Heaney Christmas card show up in the mail. Christopher Reid comments,

The sending of cards constituted a significant part of the Heaney family’s Christmas ritual. Catherine Heaney recalls that every December her father ‘approached the task with the rigour and planning of a small military operation.’ The cards themselves carried poems, often newly written, or lines from his poems, and might be illustrated by a member of the family.

The demands on the family’s privacy must have taken an extended toll because Heaney’s wife and children did not allow any family letters to be printed in Reid’s collection; though their decision detracts from the book, it’s hard not to sympathize. Meanwhile, poems about marriage and family are scarce in Heaney’s oeuvre, but they are choice. “A Kite for Michael and Christopher,” written for his two sons, is among my favorites. The emotions it evokes are those that any parent can relate to. He writes about flying a kite his sons have made, “a tightened drumhead, an armful of blown chaff” climbing the sky “far up like a small black lark.” Subtly but surely, it becomes clear he is not talking just about flying a kite. It’s a poem about the legacy he will leave. The last stanza is poignant, fraught with meaning:

Before the kite plunges down into the wood

and this line goes useless

take in your two hands, boys, and feel

the strumming, rooted, long-tailed pull of grief.

You were born fit for it.

Stand in here in front of me

and take the strain.

It was a delight to go to the pub with Seamus, to share a meal, to smoke a cigar with him. He was wonderful company. So it’s a shame that so many of the letters reprinted here trace the development of a literary career rather than offering glimpses of the man himself. One turns with pleasure to letters such as the one written to David Hammond, the singer and broadcaster from Belfast: “I did nothing all day yesterday but sit about the McCabes’ flat, doze, go out and drink soft pints of bitter, fart, daydream, eat an Indian meal, fart again and sleep for eight hours again last night. Now the birds are singing in the garden, it’s nine in the morning and it’s all clear.”

Chief among his close poet friends were Michael Longley, Czesław Miłosz, and Ted Hughes. Longley was a compadre from his early days in Belfast. As for Miłosz, in 1987 Heaney wrote the great Polish poet a sort of fan letter, using a metaphor drawn from his childhood on the farm:

The tone and substance of your poetry ploughs a deep furrow in me. During the last eight or nine years, the register of your music as much as the level, wide, unfooled gaze of your vision has been like a sanctuary for me: reliable, confirming but not too comforting.

Hughes was exactly the model Heaney needed when trying to create poetry out of the world he knew, a body of work deeply rooted in country life, straightforward and urgent, striking to the core of existence as he understood it. Just as Hughes’s poetry emerged from his vision of life in the English countryside, Heaney gave an indelible voice to Irish rural traditions. In 1994, Heaney wrote Hughes a long, sympathetic letter in response to the English poet’s marvelous late critical book, Winter Pollen:

More and more when I think of you, I think of the immense complexity of your sorrows and constraints, of the stove-hot labyrinth you’ve been caught in; what one took for granted—the abundance and ecology of your whole work—seemed a marvellous feat of total integration, intelligence, total vocation, sacrifice of the social self to the imagined dimensions of the calling.

When Hughes died of cancer in 1998, Heaney spoke at the funeral service in Westminster Abbey, where Britain’s most eminent writers were assembled, a choir delivering Thomas Tallis’s Spem in alium full-out into the abbey’s echoing vastness.

Afterward he wrote to Hughes’s widow, Carol, commenting, “Strange how we were all there, heavy in the big glittering net Ted had woven out of his poetry and personal beauty.” He wished, moreover, that he could have dedicated the translation of Beowulf he was then working on to his departed friend while he was alive to appreciate it—“not only because he fostered me as a poet, but because he was like the minstrel who sings in Heorot Hall, ‘telling with mastery of man’s beginnings, / how the Almighty had made the earth / a gleaming plain, girdled with waters’. And so on. It belongs to him.”

It makes perfect sense for him to cast his admiration for Hughes within the context of the Old English epic. Heaney, Miłosz, and Hughes created their poetry within a living continuum that encompassed the earliest literary traditions, understanding these traditions to be the common property of all. As the ghost of James Joyce reminds him in Heaney’s masterpiece, the Station Island sequence, “The English language / belongs to us.” His friend Derek Walcott wrote Omeros, a Caribbean version of Homer’s epics, just as Joyce had done an Irish take in Ulysses. Like Miłosz, Heaney grappled with the political conflicts of the contemporary world from a perspective deeply aware and respectful of tradition. Station Island, though set within the framework of the Catholic pilgrimage to St. Patrick’s Purgatory in Lough Derg, County Donegal, reads like a modern-day reprise of Dante’s Inferno, where the poet, accompanied by an older guide, encounters the spirits of the dead. At the same time, as a part of Heaney’s ongoing story of self-discovery and poetic self-fulfillment, Station Island fits into the tradition of Wordsworth’s The Prelude, which is subtitled “Growth of a Poet’s Mind.”

Heaney’s last years were clouded by poor health. First a stroke, then heart trouble, finally a fall that proved fatal. But he kept his chin up, stayed strong for those who counted on him, and his sense of humor did not desert him. Reporting on having a pacemaker implanted, he wrote, “The surgeon was in his togs when I was wheeled into the theatre, everybody masked up, me on my back on the gurney, so he asks, as he strops the knife—‘Have you any questions?’ Me: ‘Do you come here often?’ He: ‘Only when I’ve a couple of drinks on me.’ I knew he was the man for the job.”

In our age of digital communications, it’s fitting that this collection of letters ends with a text message. On the day of his death, he texted to his wife in Latin: Noli timere, “Don’t be afraid.” As Reid comments, the message has acquired proverbial status. I’ve seen it painted in large letters on the side of a building in Dublin. In these troubled and troubling times, it’s a good message for all of us.