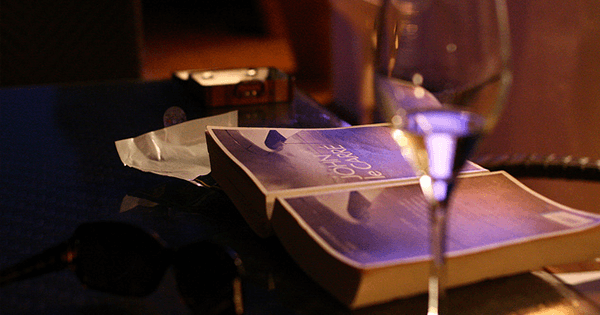

The Pigeon Tunnel: Stories From My Life by John le Carré; Viking, 320 pp., $28

One evening in the early 1960s, MI6 intelligence officer David Cornwell was killing time at a bar inside London City Airport before catching a flight back to his post in Bonn. A gruff-looking man appeared and asked the bartender for a whiskey. The stranger finished his drink quickly and walked off, concluding a brief and utterly forgettable encounter that nonetheless ignited Cornwell’s imagination. “There was a deadness in the face,” Cornwell later told The Paris Review. “It was the embodiment, suddenly, of somebody that I’d been looking for … I never spoke to him, but he was my guy, Alec Leamas, and I knew he was going to die at the Berlin Wall.”

The resulting 1963 novel, The Spy Who Came In From the Cold, catapulted John le Carré (Cornwell’s nom de plume) into the literary stratosphere, where he has remained ever since. Espionage is le Carré’s lodestar, but don’t mistake him for just another scribbler of airport paperbacks; his novels—23 so far—exemplify that most coveted of literary achievements: deeply serious, insightful, and deftly written works that also happen to be international bestsellers.

In the early pages of his latest offering, one of le Carré’s rare forays into nonfiction, we find him sitting at his writing desk in the mountaintop Swiss chalet he bought with the windfall from The Spy Who Came In From the Cold. Less a memoir than a disparate collection of reminiscences, The Pigeon Tunnel contains what le Carré calls “tiny bits of history caught in flagrante,” all of them borrowed from the lived experience of a novelist whose career has more closely resembled that of a war correspondent than a literary celebrity.

Le Carré left the intelligence business in 1964 to devote himself more fully to writing, but his life has been no less of an adventure for that. The Pigeon Tunnel reads like outtakes from a reporter’s notebook, which makes sense, given le Carré’s globetrotting creative process. Early in his career, he relied solely on his imagination for characters and settings. But after an outdated Hong Kong guidebook sabotaged the authenticity of a chase scene in his 1974 novel, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, le Carré resolved that he would never again write about a place he hadn’t visited. “The lesson I had learned wasn’t just about research,” he writes. “It told me that in midlife I was getting fat and lazy and living off a fund of past experience that was running out. It was time to take on unfamiliar worlds.”

And he did just that, trotting off to Cambodia and Vietnam with Washington Post correspondent David Greenway. Not more than a couple of weeks after the guidebook snafu, he writes, “I was lying scared stiff beside [Greenway] in a shallow foxhole, peering at Khmer Rouge sharpshooters embedded on the opposite bank of the Mekong River. Nobody had ever shot at me before.” Over the next 40 years, in the tradition of his friend and fellow MI6 alumnus Graham Greene, le Carré traveled the world in search of characters to populate his pages—to Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, Russia, Panama, Kenya, and eastern Congo.

Along the way, he was shot at, yes, but also feted and often, either on the strength of his books or on the incorrect assumption that he maintained ties to British intelligence, allowed access to some of the world’s wariest people. Heads of state, former spymasters, mobsters, arms traffickers, warlords, mercenaries, and terrorists—they crowd le Carré’s recollections just as they do his novels. In the early 1980s, for example, hoping to be assured of safe passage in Beirut to research The Little Drummer Girl (1983), le Carré met with Yasser Arafat at the Palestinian leader’s secret hideout. Convinced of the novelist’s good intentions, Arafat granted the request and sealed the deal with a ceremonial embrace and kiss. “The beard is not bristle, it’s silky fluff,” le Carré writes, remembering his amazement. “It smells of Johnson’s Baby Powder.” Such were the small yet crucial bits of intimate detail with which he constructed stories that were, as much as possible, true to life and that continue to stand head and shoulders above other works of genre fiction.

Spies are le Carré’s preferred subject, but through them he grapples with larger human truths that transcend the cloak-and-dagger underworld. Like his novels, The Pigeon Tunnel addresses questions of loyalty, love, and betrayal, the limits of suffering, and the inevitability of conflict. In this world, le Carré writes, “the harder you looked for absolutes, the less likely you were to find them.” But then, absolutes are boring, aren’t they? The same could never be said of le Carré’s novels—or as The Pigeon Tunnel demonstrates, of the man himself.