Maybe it’s the grass, or the royals, or the hallowed significance of Centre Court, but Wimbledon has been a cruel tennis mistress for more than a few players, a tear-evoking executioner of major dreams. Recall Jana Novotna crying on the shoulder of the Duchess of Kent after choking against Steff Graf in 1993, or Andy Murray sobbing after his 2012 loss to Roger Federer. Rare is the player who comes through without first enduring heartbreak. Even rarer is the player who, in hoisting the trophy, shakes up the sport’s hierarchy, reshapes its power dynamics. Think back to the 2008 men’s final, when Rafael Nadal defeated Federer 9-7 in the fifth set amid the encroaching dusk, effectively establishing himself as a bona fide rival to the previously untouchable Swiss.

Two Sundays ago, in one of those rare epoch-defining matches, a five-set, nearly five-hour smackdown of a Wimbledon final, Carlos Alcaraz defeated Novak Djokovic. For some time now, the recurring storyline in the men’s game has been the future—namely, when will the next generation finally challenge the Big Three? With the retirement of Federer last fall, and Nadal’s recent hip surgery, Djokovic, 36, has enjoyed a period of unchallenged supremacy: he won his record 23th major at the French Open in June. He has engineered his late-stage dominance by fashioning himself as the human equivalent of a backboard, albeit it a backboard with the elasticity of a rubber band, one that can chase down balls and turn matches into survivalist challenges, his opponents reduced to quivering shells of indecision. Arriving in England this year, he had hoisted four consecutive Wimbledon trophies and appeared to have a reasonable chance at the calendar Grand Slam, a feat last achieved on the men’s side by Rod Laver, in 1969. Picture a king dining at a royal banquet, no one else invited to the feast.

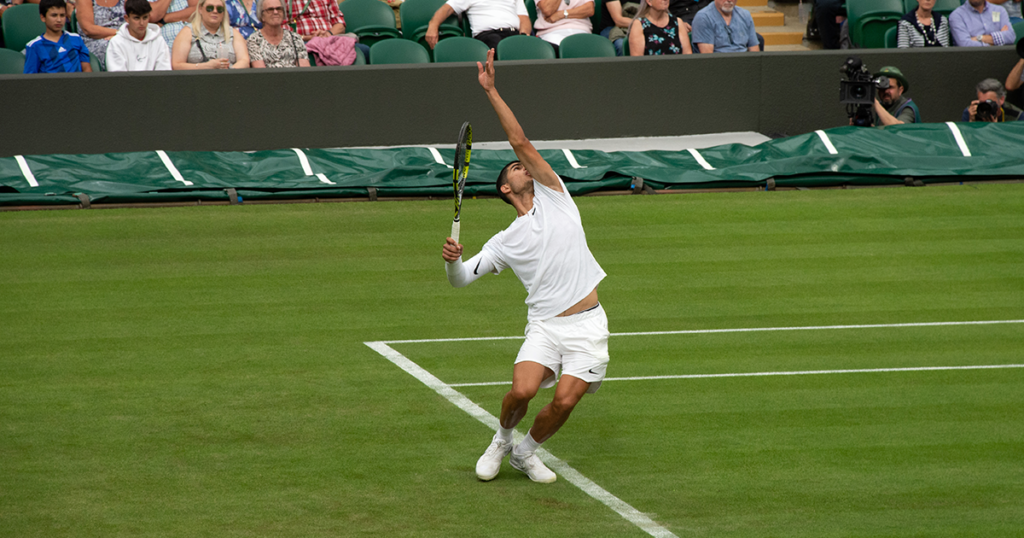

But with his stunning victory, Alcaraz, a 20-year-old Spaniard, confirmed what fans have long suspected: that he’s a transcendent, generational talent, one who can headline a new era in tennis. At the French, he had succumbed to Djokovic after cramping; at Wimbledon, his relative inexperience on grass made a breakthrough unlikely. A man of lesser mental fortitude—or tactical acumen—might have wavered after getting steamrolled 6-1 in the opening set, or after Djokovic earned a set point in the second set tiebreaker. Instead, it was Djokovic who got tight, dumping two backhands into the net, before Alcaraz leveled the match with a cinematic, backhand, return-of-serve winner. In the decisive fifth set, which is ordinarily Djokovic’s domain, one he lords over with knowing assurance, Alcaraz exhibited a warrior’s spirit, with a succession of drop shots, 100-mile-an-hour forehands, topspin lobs, and stretch volleys—to say nothing of his quick-footed defense—leaving Djokovic to slam his racquet into the wood net post in frustration. “This is everything any of us could possibly have hoped for,” enthused John McEnroe, who seemed equally awed by the Spaniard’s fearlessness, and delighted by his impending reign.

The fortnight featured no shortage of compelling storylines. Andy Murray, 36, playing with a metal implant after two hip surgeries, arrived hoping to fashion one more major run. In the second round, against fifth-seeded Stefanos Tsitsipas, Murray collapsed to the court holding his groin after an awkward slide at the end of the third set, his shriek so haunting that you wondered for a moment if the injury was career-ending. He walked it off, soldiered on, before losing a two-day affair in five sets; his remaining time on tour appears fleeting.

At least Murray showed up. The Australian Nick Kyrgios withdrew from the tournament thanks to a wrist injury and has seemed in no rush to return to the tour following knee surgery earlier this year. “I don’t miss the sport at all,” Kyrgios said in a recent interview. “I was almost dreading coming back a little bit.” One of the all-time enigmas in tennis history, Kyrgios, 28, made the Wimbledon finals last year, when he appeared on the verge of posting some results commensurate with his preternatural talent. But now his future appears much in doubt, his legacy—a complicated one at that—likely to be colored by a dubious (and debatable) distinction: most gifted player never to have won a major.

Contrast that with the emergence of Christopher Eubanks, the 27-year-old American who played his college tennis at Georgia Tech. At the beginning of the year, Eubanks had never cracked the top 100; he called grass the “stupidest” surface after losing in a Wimbledon warm up event. And yet he proved to be the revelation of the tournament, managing to ride his outsize forehand and net play to the quarterfinals, before falling to the Russian Daniil Medvedev in five sets—a match featuring two of the lankiest big men on tour: Medvedev stands 6’6, Eubanks 6’7. With his stork-like wingspan and dynamic personality, Eubanks appears poised for a stadium-shaking run at the U.S. Open later this summer.

On the women’s side, the final marked less of a generational shift than a reminder of how cruel Wimbledon can be. Ons Jabeur, the 28-year-old Tunisian, recorded runner-up finishes at the All England Club and the U.S. Open last year. Her rise and undeniable charm—she is Tunisia’s unofficial Minster of Happiness—have inspired women throughout the Arab world. Her goal during the tournament glowed on her iPhone home screen: a picture of the Venus Rosewater dish, awarded each year to the champion. Jabeur dispatched third-seeded Elena Rybakina in the quarters, second-seeded Aryna Sabalenka in the semis, and entered the final as the heavy betting favorite. Her opponent: Markéta Vondroušová, the 24-year-old Czech player with the thin-lined tattoos of a minimalist painter. A French Open finalist in 2019, Vondroušová was unranked, having been sidelined by recent injuries, her wrist in a cast last summer following surgery. Surely this was Jabeur’s moment. She took an early 4-2 lead in the first set. Then, disaster: Vondroušová reeled off five straight games. As the match slipped away, Jabeur appeared uncharacteristically flat, both physically and emotionally, her fighting spirit hardly in evidence. It was a bizarre turn, and in the post-match ceremony, the gravity of the moment finally registered. Like so many before her, tears flowed. “The most painful loss of my career,” Jabeur called it.

All of which sets up some epic storylines for this year’s U.S. Open. Can Jabeur finally hoist major hardware? Or will Iga Świątek, the Polish number one, reassert her recent dominance and win her second slam of the year? On the men’s side, how will Djokovic respond to his Wimbledon defeat? In recent years, his has been a divisive legacy on tour, in part because of his refusal to get the Covid vaccine—a decision that probably cost him at least one slam—and his political stances, which detractors have equated with Serbian nationalist propaganda. Early in his career, he played the role of jokester, mastering a series of impressions of his fellow tennis stars that he cycled through in on-court interviews. He yearned to be liked then, or it seemed. But during this most recent Wimbledon fortnight, he embraced the role of bad-boy villain, drawing inspiration from the haters. In his semifinal match against Jannik Sinner, with the crowd buzzing with support for the 21-year-old Italian, Djokovic pantomimed the wiping away of fake tears after saving a couple break points and holding serve: a metaphorical middle finger to those in the stands. Then there was his methodical ball bouncing before service (the pock-pock-pock like the rapid ticking of a clock), which earned him a couple of time delay warnings during the tournament—at best it is an annoying tic, at worst a ploy to gain a competitive advantage.

Is Djokovic the G.O.A.T, the greatest of all time? I find the question reductive, for reasons I recently outlined. But the Serb now has a chance to add to his considerable legacy, if he can find some way to reassert his supremacy in the face of Alcaraz’s newfound level. In defeat, Djokovic was all class, praising the Spaniard as the embodiment of the best qualities of the Big Three: “I’ve never faced a player like [him].”

As for Alcaraz, fans should bow before the altar of the tennis gods, light a few candles, and offer up pleading invocations that he remains injury-free. While they’re at it, they can implore his talented contemporaries to seize on his victory as evidence that they, too, can achieve a major breakthrough. One thinks especially of Sinner, the young Italian with the unruly mop of red hair (some of his fans dress up as carrots), and the tempestuous Holger Rune, the 20-year-old Dane, both of whom have the appearance of a champion. But for the moment, it is Alcaraz’s world. Watching him at Wimbledon was like witnessing the future in real time—an intoxicating sensation that leaves one thirsting for more.