When I turned on the Tony Awards about a year ago, I thought I knew Fun Home. I had read the book on which the musical was based, cartoonist Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoir, and several friends had given detailed, glowing reports of its sold-out run at New York City’s Public Theater. The show had moved on to Broadway, but I felt no particular urgency to see it. For one thing, I couldn’t imagine how Bechdel’s book, depicting her coming of age as a lesbian and her tormented relationship with her father—using a combination of captions, speech bubbles, and drawings to convey multiple levels of information and meaning—would translate to the stage. But when the cast performed a scene during the Tony Awards broadcast, I realized with excitement what I had been missing.

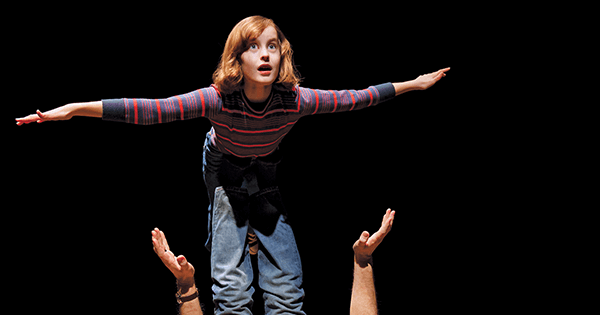

While Sydney Lucas (playing Bechdel as a young girl) and Michael Cerveris (as her father) carried on a tense conversation, Beth Malone, playing the adult Bechdel, offered a monologue from her drawing table, off to the side: “In this panel, me and my dad in a diner. Caption: My dad and I both grew up in the same small Pennsylvania town, and I didn’t know it, but both of us were gay. And we were exactly alike. And we were nothing alike. Which was it, Dad?” That question hung in the air as Lucas walked across the stage to sing “Ring of Keys,” the haunting confession of a nine-year-old girl suddenly galvanized to recognize her inchoate sexual orientation.

The music beautifully captured the character’s journey from ambivalence to confidence, the fractured musical phrases coalescing into a soaring melodic line as the exuberant chorus was reached. It was a magical few minutes, moving, full of drama, and this one number showed me that lyricist Lisa Kron and composer Jeanine Tesori were as ambitious as Rodgers and Hammerstein and Stephen Sondheim—artists who knew that no subject was off-limits in musical theater. Well before it received the Tony for best musical at the broadcast’s close, I knew I had to see Fun Home right away.

The production was a revelation, overwhelming me from the first word—“Daddy,” of course. My alcoholic father had been the same kind of angry, overbearing presence in my childhood home that Bechdel’s was in hers, and the concordances between the two began to resonate almost immediately. Early on, the family tidies up the Victorian house that Bruce Bechdel has meticulously restored, in preparation for a visit from the Allegheny Historical Society. While he dresses for the occasion, Alison’s mother, Helen, sings anxiously, “What are we missing? What have we left out? When he comes down here, what’s in store?” I remembered for the first time in years my own mother telling me, after she divorced my father, “I couldn’t cope anymore with never knowing what I was going to find when I opened the door.” Dialogue and songs continued to stir up unsettling memories throughout the wrenching, intermissionless 100 minutes. I was weeping when the lights came up for the curtain call.

My response to this universal family drama of mingled love and rage, guilt and regret, alienation and reconciliation was intensely personal, but not unusual. I’ve seen the musical twice now, and both times a good portion of the audience has been reduced to tears. I suspect it will be the same across the country after Fun Home begins a national tour in October.

In her book, Bechdel weaves together significant moments from her life in nonchronological fashion. To embody that interplay of recollection and reflection onstage, Lisa Kron divides Alison into three: Small Alison, Medium Alison (who enters the play as a freshman at Oberlin), and the adult Alison, who quietly observes the action, stepping forward to comment, offering a blunt exegesis of her life story.

“He was gay, and I was gay,” says the adult Alison, “and he killed himself, and I … became a lesbian cartoonist.” We have been forewarned. This is a memory play—not a play about what happened, but a play about trying to make sense of the past. Onstage, the characters move seamlessly among time frames. The 43-year-old cartoonist Alison steps away from her drawing table (which sinks into the stage floor) and walks to the edges of the Bechdels’ overdecorated parlor or Medium Alison’s dorm; the rooms’ furniture springs up in physical space as she conjures up their emotional contents. Trying to corral her memories into a book about her father, the adult Alison recaptures plenty of angst but also a surprising amount of laughter, the latter often at the expense of Medium Alison. Who isn’t amused and embarrassed by her teenage self?

Medium Alison is wincingly vulnerable and hilariously maladroit as she grapples with her sexuality: losing her nerve at the door of the gay student union, she pretends to be looking for the German club. After she falls into bed with a classmate, her happiness is infectious. “Changing My Major” is the show’s most charming song: exuberant, sexy, corny, yet witty; Cole Porter might have crafted some of the cleverer lines, if he’d been able to write this openly about same-sex attraction. For Alison, joy comes not only from finding someone but also from finding herself at the same time.

“Caption: I leapt out of the closet,” the adult Alison tells us. “And four months later my father killed himself by stepping in front of a truck.” In the scene that follows, we see Bruce once again forcing his young daughter to conform to the same narrow social conventions that have required him to masquerade as a heterosexual. Small Alison proudly shows her father a map she’s making for school “of all the places people in our family have been to.” It’s a sprawling proto-cartoon encompassing everything from a keystone (“because Pennsylvania is the Keystone State”) to the town in Germany where Bruce and Helen lived when they were first married. Bruce browbeats her into making a more orthodox picture just as he bullied her before to wear a party dress she despised. Small Alison once again submits. The adult Alison steps forward to take the drawing from her hand and sing “Maps.”

It’s her reckoning with the restricted geography of her father’s life, the boundaries she erased by telling the truth about herself.

Four miles from our door

I-80 ran from shore to shore

On its way from the Castro to Christopher Street

The road not taken, just four miles from our door

You were born on this farm

Here’s our house

Here’s the spot where you died

I can draw a circle

I can draw a circle

You lived your life inside.

Perhaps because it tells my straight father’s story too, I can see that “Maps” is not exclusively about Alison’s father as “a tragic victim of homophobia,” a narrative Bechdel explicitly rejects in her book. Bruce’s tragedy, and my father’s, was judging himself by other people’s standards. Both of them chose to live inside circles that had no room for who they really were. My father’s circle measured success by his income and by the prestige of his job. At least Bruce finds some fulfillment in the obsessive restoration of his museum-like home; his great final song, “Edges of the World,” shows him desperately taking on another old wreck of a house, hoping somehow to clean up his shame and frustrations along with its sagging roof and buckled walls. My father loved making furniture, but the moderately successful business he made of it after he drank himself out of a series of jobs in television could never compensate for the high-status, high-pressure positions he had hated yet felt he ought to want. I couldn’t bear hearing him talk about himself as a failure, but I was too young to know how to shut down his drunken confidences, just as Small Alison is too young to assert herself against her father’s insistence on conformity. I fled to college, relieved to leave my mother and siblings to deal with it all.

The adult Alison’s anguished confession, “I blocked out everything that was happening at home,” struck an uncomfortable chord. Even more discomfiting was Helen’s bitter song in reply to Medium Alison when, after learning about her father’s homosexual affairs, she asks how her mother stood it. “Days and Days” chronicles a hopeful, youthful marriage soured into the grim execution of wifely duties and reaches its shattering conclusion with the lines, “Don’t you come back here / I didn’t raise you / To give away your days / Like me.” My mother never said anything so direct, but I stayed away anyway. I was in love, and my future husband’s family seemed refreshingly normal. (Later I would learn—and why on earth was I surprised?—that they too had secrets and conflicts.) My guilt when I got a phone call at college alerting me to the first of my father’s several hospitalizations for alcoholism can’t possibly compare with what Bechdel must have felt when she heard of her father’s suicide, but it was devastating enough.

“I should have been paying attention,” wails the adult Alison. “I didn’t know, Dad. I had no way of knowing my beginning would be your end.” Few of us have to worry about whether we caused our father’s suicide, but children’s beginnings and parents’ ends are conjoined in every family. We all have to deal with growing up and leaving home. By the time I saw Fun Home, my son had started college, and I had experienced that separation from the other side. No matter how satisfying your work or marriage, watching your child begin a life apart from yours elicits mixed feelings. Only now do I better understand how my departure destabilized my family’s already shaky equilibrium. It wasn’t my fault, but I was implicated in my father’s unraveling and the disintegration of my parents’ marriage.

I was lucky. After my mother finally left him, my father miraculously quit drinking—he had been sober for nine years when he died. We lived just a few blocks apart, and I saw a lot of him, though he hadn’t become any easier to get along with. He remained angry and unhappy, given to self-pitying monologues about how badly his life had turned out. I slowly learned how to let him briefly vent, then firmly—okay, sometimes furiously—tell him to let it go. I had time to grow up enough so that I could love Dad for the man he was: smart, funny, difficult, screwed up. Bechdel had to get to that point in her father’s absence; their single, inconclusive conversation about their sexuality, during an agonizing car ride, is Fun Home’s saddest song.

Fun Home’s warm, rueful finale begins with the adult Alison abandoning her attempt to make sense of her father’s life. “This is what I have of you,” she says, holding a stack of individual drawings she has vainly tried to organize into a coherent narrative. Paging through them, she stumbles on the one that tells her what she’s really been looking for: “You … succumbing to a rare moment of physical contact with me.” Small Alison appears, then Medium Alison steps into the light, and we witness the adult Alison at last seeing her father whole and realizing that this is enough. “There you are, Dad,” she says, looking at one of her drawings. “There you are.” This moment of hard-won acceptance launches the show’s radiant closing song, “Flying Away.” All three Alisons sing together, affirming the connection to our past that can never be broken and the need to fly free that transforms us into adults. l