Who would have guessed that Shakespeare included a crowdsourcing campaign in A Midsummer Night’s Dream?

In the play, after all, it takes the collective memory of four lovers, a king, and his betrothed to piece together exactly what happened the night before. As King Theseus puts it, “The lunatic, the lover, and the poet are of imagination all compact.” In the same team spirit this winter, in preparation for the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., has started its own crowdsourcing operation, Shakespeare’s World, which allows volunteers to transcribe English Renaissance manuscripts into a digital archive.

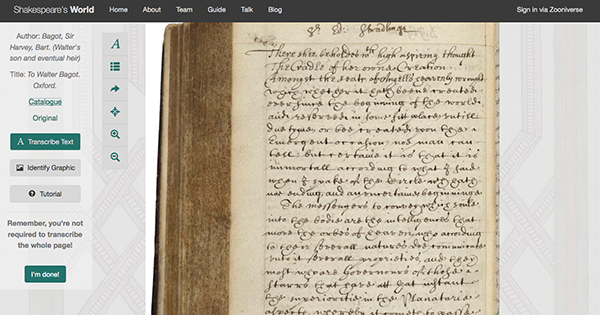

The Folger partnered with the popular citizen-science platform Zooniverse to create Shakespeare’s World. Since the website launched last December, nearly 15,000 volunteers have digitally recorded about 25,000 documents—mostly letters and recipes—written by Shakespeare’s contemporaries. The website is open to anyone who wants to learn more about what the general public was up to in the 16th and 17th centuries, especially women and the working classes. “The potential is endless,” says Heather Wolfe, the Folger’s curator of manuscripts and principal investigator of its Early Modern Manuscripts Online (EMMO) program. “We are hoping that the corpus will be used by scholars, teachers, students, and anyone who is interested in Renaissance England.”

Volunteers might also uncover previously undocumented words. At least that’s the hope of the publishers of the Oxford English Dictionary, another partner. Case in point: in mid-December, the first word discovery was recorded—Taffytie, which is thought to be an early modern English variant of taffeta.

Using an online forum, five volunteers collaborated to document the new word variant. “Working on paleography in a group setting is quite effective,” says Paul Dingman, EMMO project manager. Old handwriting can be cryptic, so volunteers help each other via the chat forum. Most of the manuscripts contain abbreviations and are rife with letter crossovers like u for v and i for j. Also, there were no universal spellings—just guidelines, really—and vestiges of Old English remained in the mix. Thorns, for example, can entangle the reader: the letter that looks like a y but sounds like th, as in ye olde shoppe.

Interested in volunteering? The project will run for at least three years. To invoke Queen Hippolyta, with “all their minds transfigured so together,” the transcription project could “grow to something of great constancy.”