In the land of the free and the home of the brave, the degree to which fundamental concepts like “liberty,” “rights,” “free speech,” “defiance,” and “self-defense” have been historically racialized is arguably nowhere more visible than in the Black military experience. Traditional attitudes toward African Americans in uniform have implications for our understanding of the ongoing policing of Black bodies across the nation. The fear and animus stoking law-enforcement violence against Black Americans can also be discerned at the root of earlier longstanding policies prohibiting outright, or radically restricting, African-American military service dating back to the Revolution, when the British cannily offered enslaved men their freedom in exchange for defending the rights of the king.

Several thousand Black men, enslaved and free, ended up serving in the Continental Army, for the most part in integrated units, but once the crisis was over, Congress passed the 1792 Militia Act limiting enrollment to “white male” citizens. It would not be amended for another 70 years, when emergency again compelled the enlistment of “persons of African descent” for “military or naval service” in 1862. By the end of the Civil War, approximately 180,000 Black soldiers had served in the Union Army, about 10 percent of the total force.

The connection between full political participation and the bearing of arms to defend the republic dates to antiquity. In the United States, especially during the early national and antebellum eras, the citizen-soldier’s obedience—a thinking, willing obedience—was routinely defined against both the blind obedience of the European conscript and the cringing, compelled obedience associated with the slave. That is why the Confederate congress refused until the desperate end of the Civil War to consider arming the enslaved: that action would have affirmed chattel to be human beings.

As the white abolitionist Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who commanded a regiment of newly freed slaves in South Carolina, wrote, “Till the blacks were armed, there was no guarantee of their freedom. It was their demeanor under arms that shamed the nation into recognizing them as men.” Confederate policy regarded Black Union soldiers as not enemy combatants but fugitives to be re-enslaved or otherwise “dealt with” by state authorities, while their captured white officers, “deemed as inciting servile insurrection,” were to “be put to death or be otherwise punished.”

In practice, Black soldiers were often given no quarter; at best, their fate was wildly uncertain. The April 1864 massacre at Fort Pillow, Tennessee, which reminded one Confederate of a slaughterhouse awash in brains and blood, is only the most notorious example of the treatment received at enemy hands. Soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, the war’s most celebrated Black regiment, participated in the assault on Fort Wagner, South Carolina, in July 1863, knowing full well that, in the words of Captain Luis F. Emilio, their enemy regarded them as “outlaws.”

When the Confederates refused to include Black soldiers captured at Fort Wagner in the customary prisoner exchange, President Abraham Lincoln tried to protect them by issuing General Order 252: “It is, therefore, ordered that, for every soldier of the United States killed in violation of the laws of war, a rebel soldier shall be executed, and for every one enslaved by the enemy or sold into Slavery, a rebel soldier shall be placed at hard labor on the public works, and continued at such labor until the other shall be released and receive the treatment due to a prisoner of war.”

The ultimate dishonor the fort’s Confederate commander, Brigadier General Johnson Hagood, could imagine for the dead body of Robert Gould Shaw, the white colonel of the 54th, was to throw it into a ditch together with the bodies of his men, a gesture dramatized in Robert Lowell’s poem “For the Union Dead.” Despite outraged demands in the North for the return of the colonel’s body, Shaw’s father, refusing to legitimate Confederate logic, insisted the corpse remain in its noble company.

In the months before the attack on Fort Wagner, the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards participated in a wasteful Union assault on Port Hudson, Louisiana. In one of those strange paradoxes of antebellum Louisiana, the unit was first created by the Confederate state government in 1862, as a militia of free persons of color: it was an organization, the historian Stephen J. Ochs explains, “intended for show and not for combat.” Disbanded after the Union capture of New Orleans, the officers reformed a militia and volunteered for federal service. Relegated to manual labor, submitted to various indignities and abuses, the soldiers finally got the opportunity to fight in the late spring of 1863.

By this time, following Union Army practice, most of the regiments’ original Black officers had been replaced by whites. Among the exceptions was Captain André Cailloux, commanding E Company, 1st Regiment, who, according to William Wells Brown, one of the earliest historians of the Black military experience in the Civil War, “prided himself on being the blackest man in the Crescent City.” Cailloux was killed alongside many of his men in the attack. Afterward, the enemy permitted Union burial details to collect only white bodies, so the corpse of Cailloux rotted together with those of his men in the summer heat until the besieged Confederates surrendered more than a month later. In the end, he could be identified only by a ring signifying his membership in one of New Orleans’ many Afro-Creole civic organizations.

Brown and many others celebrated Cailloux as a hero who was, as his ring attested, a citizen as well as a soldier. Another officer in the Louisiana Native Guards, P. B. S. Pinchback, would become lieutenant governor of Louisiana in the early 1870s and, for a month, Reconstruction’s lone Black governor. As the violent resistance to Reconstruction attested, African-American social and political power, even when peacefully exercised, proved as threatening to traditional white southern authority as did the prospect of armed insurrection.

Black men in uniform, the historian James M. McPherson observes, “carried disturbing implications” for white soldiers resistant to the notion of Black equality. A number of Civil War policies marked out Black soldiers as less than equal. At first, they were paid less than their white counterparts, while regiments of newly emancipated slaves received even less than troops from free states. Pinchback himself resigned from the Army over pay and other inequities. After Fort Wagner, members of the 54th Massachusetts refused to accept any pay until they were given the same monthly salary as their white comrades. “Are we Soldiers, or are we Labourers?” Corporal James Henry Gooding pointedly asked President Lincoln in 1863. The South Carolina regiments were also issued scarlet trousers rather than the regulation blue. Irregular uniforms rankled both Higginson and Frederick Douglass, one of the strongest proponents of African-American military service, who deemed them “a badge of degradation.”

Striking though they did, in Douglass’s words, “for manhood and freedom,” Black soldiers were repeatedly denied the opportunity to prove themselves on the battlefield because they were judged incapable of the kind of courage under fire supposedly attainable by white soldiers. Not for the last time, the Army preferred to use Black soldiers as teamsters, cooks, orderlies, or members of burial details. A white captain who fought at Milliken’s Bend in June 1863, in the midst of the Vicksburg Campaign, became infuriated by complaints that Black soldiers wouldn’t fight. “Come with me 100 yards from where I sit,” he wrote, “and I can show you the wounds that cover the bodies of 16 as brave, loyal, and patriotic soldiers as ever drew bead on a Rebel. … [T]hey fought and died defending the cause that we revere.”

One of several factors contributing to the disastrous failure of the Battle of the Crater, at Petersburg, Virginia, the following year, was General George G. Meade’s last-minute replacement of the division of Black troops rehearsed to lead the attack by unprepared white soldiers whose commander was allegedly drunk during the battle. Commanding general Ulysses S. Grant, far more well-disposed to African-American military service than most, bowed to the objections of his subordinate even though he thought the Black soldiers would have succeeded. Grant testified before the Committee on the Conduct of the War, “Meade said that if we put the colored troops in front … and it should prove a failure, it would then be said, and very properly, that we were shoving these people ahead to get killed because we did not care anything about them. But that could not be said if we put white troops in front.” Ordered to follow the white vanguard into the Crater (the hole made by a mine exploded under the Confederate works), many of the Black soldiers lucky enough to survive that hell were shot trying to surrender.

Douglass’s forceful articulation of the connection between wearing the uniform and acquiring citizenship serves as the epigraph to almost every history of the Black military experience: “Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters, U.S.,” Douglass wrote in 1863, “let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder, and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on earth … which can deny that he has earned the right of citizenship.” But after the Civil War, that citizenship, won by blood and secured by constitutional amendment, would be effectively rescinded again.

Douglass insisted that the “powerful Black hand” could redeem as no other the unfulfilled promise of the Declaration of Independence: “If any class of men in this war can claim the honor of fighting for principle … not from brutal malice,” he declared, “the colored soldier can make that claim preeminently.” (Douglass’ brief was not without its own troubling provocation in its juxtaposition of the Black soldier, who observed “the rules of honorable warfare,” with the Native American “savage,” who resorted to “tomahawk and scalping knife.”) But as the United States spiraled into Jim Crow at the end of Reconstruction, the image of the Black soldier as principled freedom fighter would be eclipsed in the American imagination by the radically different portrait showcased in Woodrow Wilson’s A History of the American People and sensationalized on the screen in D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, in which Black soldiers are characterized as violent, hypersexualized beasts inflicting a catalogue of horrors on white southerners until the KKK comes to the rescue.

One of the film’s most repulsive scenes, which depicts the first Reconstruction Congress in the South Carolina House of Representatives in 1871, filled with the crudest caricatures Griffith could muster, systematically repudiates the claim to citizenship won by Black soldiers. Griffith’s tableau, titled “The riot in the Master’s Hall,” dramatizes the passage of two pieces of legislation, one permitting interracial marriage, the other mandating that all whites salute Black officers in the street. Griffith devotes the rest of his film to destroying the menace of Black sexuality and violence embodied in the figure of Gus, a newly promoted captain whose attempted rape of the youngest daughter of Dr. Cameron (patriarch of the white family around which the plot revolves) precipitates the climactic confrontation between “the negro militia” and the victorious Klan.

Griffith turns the Black soldier into an uncontrollable agent of anarchy let loose on the land, while, as the film’s depiction of the Battle of Petersburg suggests, the field of honorable combat is restricted to whites. By contrast, the “irregular” guerrilla band that raids the Cameron home is Black. They are led by a “scalawag white captain” who encourages his half-dressed and frenzied soldiers to loot homes, shoot civilians, and burn the town. In Griffith’s source, Thomas Dixon’s 1905 novel The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan, the white commander of the occupying force issues a proclamation to the people of the county: “The military force in command of this district are not the servants of the people of South Carolina. WE ARE YOUR MASTERS.” Intensifying the threat of Black mastery, the federal military presence in Dixon and Griffith’s postwar South is, ahistorically, almost exclusively Black.

This postwar hysteria had its roots in the antebellum South, when the specter of the Black man in arms was the nightmare of slaveholders, who responded to the violent 1831 revolt led by Nat Turner—his hope was evidently to seize an armory—with a program of terror. This campaign would be repeatedly revived in the years to come, the zeal of its prosecutors long outlasting national will to enforce Reconstruction. Today, the image of a “powerful Black hand” raised in defiance—even in lawful protest—endures as a bugbear to broad swaths of white America.

The Army—national by definition yet, as the jurist and civil rights activist William H. Hastie noted in his capacity as civilian aide to the secretary of War during World War II, emphatically southern in “mores”—shared this discomfort. Even today, African-American underrepresentation (when compared to numbers in the Army as a whole), in the infantry, special-operations forces, and the other direct-action combat units from which the Army’s senior leadership is largely drawn, is a legacy of the organization’s historic practice of restricting Black soldiers to support roles.

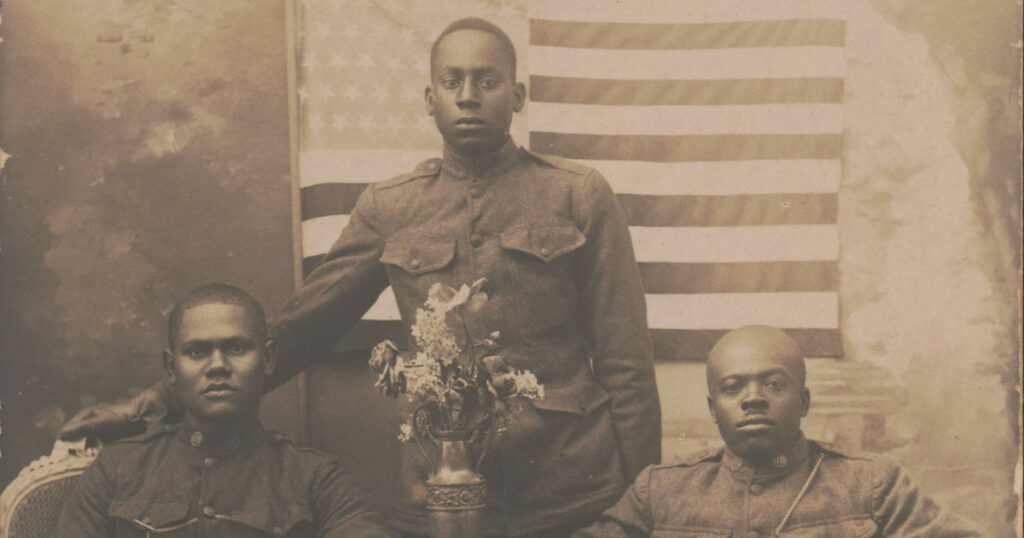

Black volunteers were turned away from recruiting offices on the eve of World War I until the Selective Service Act of 1917 mandated their enlistment, at which point they were drafted in disproportionate numbers, especially by southern draft boards. During the war, the officers of the 369th Infantry Regiment petitioned General Pershing himself to allow them to do the job they had been trained for. He farmed the 369th out to the French, who gave these soldiers—they fought valiantly alongside their new comrades—the apt nickname Les Enfants Perdus. During World War II, the reluctance to assign Black soldiers to combat roles persisted. African-American combat units such as the 92nd Infantry Division or the 332nd Fighter Group (Tuskegee Airmen) remained the exception. Most Black soldiers served in support roles, which entailed their own dangers. Assigned in significant numbers to the transportation corps, they drove trucks on the Red Ball Express, a perilous supply route across France. The 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion, formed initially “for the purpose of enhancing the morale and esprit de corps of the negro people,” and trained extensively at Fort Benning, Georgia, ended up fighting fires in the Pacific Northwest.

Conditions at Army posts North and South—segregation reached even to Fort Devens, Massachusetts—were such that James Baldwin suggested many families of African-American servicemembers “felt, mainly, a peculiar kind of relief when they knew that their boys were being shipped out of the south, to do battle overseas,” Baldwin added, “even if death should come it would come with honor and without the complicity of their countrymen.” Some northern and western states successfully resisted plans to build installations for units of Black soldiers, while southern politicians voiced their anxiety that military service would produce a political awakening among African Americans. In 1942, the Southern Governors Conference protested the assignment of large numbers of Black soldiers, many from the North, to southern posts for fear they would destabilize the status quo.

The Cold War in turn brought race prejudice and segregation to U.S. military posts in Europe. Tensions simmered there and in Vietnam before exploding after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968, which provoked cross burnings and prominent displays of the Confederate flag by American personnel in Vietnam. African-American soldiers came home from World War I, World War II, Korea, and Vietnam—come home today—to one of various posts, including some of the largest (Bragg, Hood), in states where the practice of segregation once found potent symbolic reinforcement in the presiding spirits of the Confederate generals for whom they were named, most during the Wilson administration and at the suggestion of local authorities.

These were, in a crucial sense, Jim Crow forts, their names elemental features of an architecture of racial domination, selected precisely to accommodate local affinities. Like the sculptures of Confederate soldiers standing sentinel in towns across the South, the names of the generals emblazoned on the welcome signs of Army posts formed part of a carefully curated iconography of social control. Today, Fort Bragg alone has approximately 54,000 troops and 14,000 civilian employees. According to the fort’s official website, Bragg is practically “a city in itself,” which “supports a population of roughly 260,000, including military Families, contractors, retirees and others.” More than 150 years after the end of the war that secured the emancipation of African Americans, the names of Bragg, Benning, Hood, and the rest are still broadcasting loud and clear, to civilians and soldiers alike, the signal of the masters.

To read more about the military service of African Americans during the Revolutionary War, please see Farah Peterson’s “The Patriot Slave.”