An Artist of Our Social Age

Matthew Wong broke all the rules and flourished online, but he craved what the outsider typically eschews: commercial success

Man, I’m so far gone off the painting deep end. I register virtually everything I see outside in terms of a painterly effect. Now it is really scary. I have internalized it, so it is kinda normal to me and not panic inducing, but I can imagine if a stranger were to walk these shoes for like a block they’d be terrified of how they were experiencing the world.

These words, part of a message sent to a friend during the early part of Matthew Wong’s career, offer a glimpse into the mind of a painter now recognized as one of the most celebrated of his generation. Wong suffered from debilitating mental illness—he died by suicide in 2019, at the age of 35—but during his brief life, he worked with a relentless creative energy. Though he began as an abstract artist, his later paintings render highly patterned imaginary landscapes and domestic still lifes in poignant blues, dazzling yellows, and ochres. He made each of his paintings in a single session, so as not to lose the ephemeral feelings he hoped to capture. His studios were messy, reflective of his fast and physical labor. Sometimes he would lean a canvas-in-progress against a wall and use a paper towel as a palette. As a result, paint would drip on drop cloths, his shoes, and the floor. On many occasions, he completed several canvases in a single day; sometimes, when an ostensibly finished painting had dried, he would layer another image over it. Toward the end of his life, when he was living in Edmonton, Alberta, Wong said that he would have worked 16 hours a day but for the fact that he couldn’t drive and depended on his mother to transport him to and from his studio.

In one sense, Wong reminds me of Carlo Zinelli (1916–1974), a self-taught painter and sculptor who began making art while he was a patient in a Verona psychiatric hospital and painted eight hours each day for almost the next 20 years. The paintings of Zinelli and Wong share a vibrant color sense and a flattening of perspective. Both artists transfigured autobiography into dreamlike landscapes. Zinelli was championed by the French artist Jean Dubuffet, who coined the term art brut to describe self-taught artists outside the academic tradition. Dubuffet valued art created at the furthest remove from established culture; many of the artists he favored lived with mental illness (Zinelli suffered from schizophrenia) or were otherwise marginalized. Such figures, Dubuffet believed, were untouched by the corruption of bourgeois civilization. Only art brut could express something singular and new.

In 1972, the British art historian Roger Cardinal created the label “outsider art” for the title of a book on art brut. Cardinal’s scholarship brought a large number of talented outsider artists—among them, Adolf Wölfli, Henry Darger, Martín Ramírez, Oskar Voll, and Madge Gill—into the public consciousness, in many cases posthumously. In the 1990s, the Outsider Art Fair in New York introduced to the mainstream art market work by people who loosely fit the label. In this context, the often lurid biographies of artists were crucial to the perceived authenticity of the work. “People bought the story in addition to the object,” Sanford Smith, founder of the fair, said. Critics, meanwhile, saw this as exploitative. Over time, the legitimacy of the term outsider art has been challenged for being exclusionary and derogatory because it has been used most often to describe nonwhite artists and people with mental illnesses.

And yet, Jane Kallir, a New York art dealer and curator, suggests in her essay “At a Crossroads” that the cultural embrace of outsider artists was actually a move toward inclusivity that mirrored other progressive cultural changes in the 20th century. If dominant art-history narratives were crafted largely by and for white males, many self-taught artists were women or racial and cultural minorities. Kallir also argues that the self-taught artist fits into an American mythology that exalts the nonconformist, the outcast, or the renegade. The cultural imagination always needs rebels to shake things up.

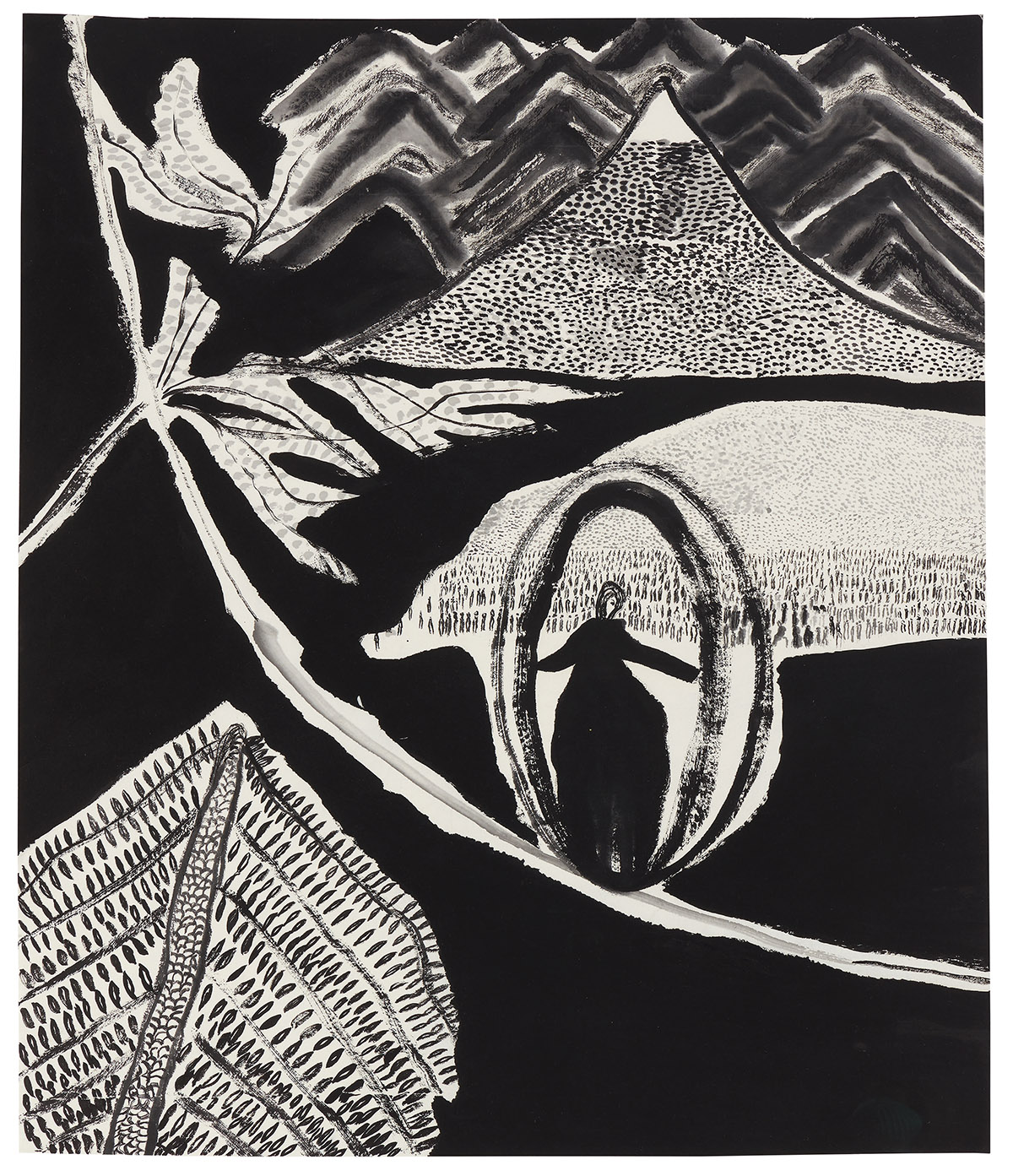

The Performance, 2017, ink on rice paper

Vivian Li, curator of a retrospective of Wong’s work opening in October at the Dallas Museum of Art, told me that the “outsider art” label doesn’t fit a painter who knew solitude intimately but who did not exist in isolation. “He had an artistic community—it was online,” Li said. In the Internet age, very few people are at the furthest remove from established culture in the sense that Dubuffet meant. Most people, regardless of circumstances, can consume whatever culture they want, which is marvelously democratic. But also, how strange that where and how we live don’t necessarily determine much about us anymore. Where was Wong from? The everywhere of the Internet, just like the rest of us. And yet, he was doing something singular and new.

The first time Li saw Wong’s painting The West was during the first months of Covid-19. She encountered it in the permanent collection of the Dallas Museum of Art (where she works) and was taken by this depiction of a single figure situated in a vast landscape of murky color, the figure facing away from the viewer. The piece reflected her lonely, uncertain mood, but it also brought her solace. Li’s colleagues at the museum responded to the work in much the same way.

Indeed, Wong’s effort to express what it felt like to be alive in his own mind resulted in paintings that make me feel lonely, but in a sublime, bittersweet way. In The West, the trees are spare, the road is empty, but the sky is awash with stars. Another work, an untitled gouache and watercolor on paper from 2019, shows the dark interior of a bedroom in shades of blue and, through a doorway, a brightly lit bathroom in yellow, the shower curtain rendered by four thick brushstrokes of baby blue. The image is intimate and evocative; it reminds me of what it felt like as a child to go to sleep with a night-light on, the unease of the dark tempered by the comfort of sharp, artificial light.

Wong was born in Toronto in 1984. His mother had moved from mainland China to Hong Kong just before the Cultural Revolution. She arrived in Canada in the 1970s, and the Wongs moved to and from Hong Kong several times. As a child, Wong was precocious and easily overwhelmed in social situations. As a young teenager, he was diagnosed with depression and Tourette’s syndrome, and his parents moved him back to Toronto, where they hoped he would benefit from the Canadian health care system.

After attending a private high school in Toronto, Wong earned an undergraduate degree in cultural anthropology from the University of Michigan. Then he returned to Hong Kong, where he worked for a short time as a corporate headhunter and as an intern at PricewaterhouseCoopers. After realizing that he was not cut out for a corporate career, he began writing poems and reciting his work at open-mic sessions. In his poems, Wong said, he hoped to capture “just a faint glimpse of a gut feeling, something in the air.”

Wong was curious about duende, an aesthetic idea, popularized by Federico García Lorca, in which some pieces of art possess a transcendent force of heightened emotion and expression. Lorca situated duende as the opposite of style and artifice; it was often experienced in the body and could be communicated spontaneously without intellectualizing. Duende was earthy. It carried an intimation of mortality. “The arrival of the duende,” Lorca said in a 1933 lecture, “presupposes a radical change to all the old kinds of form, brings totally unknown and fresh sensations, with the qualities of a newly created rose, miraculous, generating an almost religious enthusiasm.” Wong read Lorca’s lecture, and he discussed it with a friend. He would now use his formidable intellect in pursuit of this feeling, which was at once ecstatic and full of longing.

He started to take photographs and, with the encouragement of his then-girlfriend, entered a master of fine arts program in creative media, with a focus on digital photography, at the City University of Hong Kong. When Wong was a docent for the Hong Kong pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2011, he saw a retrospective of the neoexpressionist Julian Schnabel as well as abstract paintings by Christopher Wool. Inspired to draw, Wong began making abstract charcoal and ink works on paper. His work was intentionally spontaneous, allowing a random mark or the flow of the ink to lead him toward an image. “At first I just bought a cheap sketch pad along with a bottle of ink and made a mess every day in my bathroom randomly pouring ink onto pages—smashing them together—hoping something interesting was going to come out of it,” he said. “Pretty soon that was the only activity that sustained me in my daily routine.”

When a romantic relationship ended, Wong poured his energy and sorrow into his work. In 2013, his mother set up a studio space for him in Zhongshan, China. He often visited the Hong Kong Central Library to read about art and art history. At this point in his self-education, he was interested in process-based abstraction. “Wong was fascinated by what he termed the messy ‘loose ends’ of Joan Mitchell, the ‘contradictory spaces’ of Willem de Kooning and Milton Resnick, the ‘voids’ of Paul Cézanne,” writes Li in The Realm of Appearances: The Abstract Reality of Matthew Wong, the catalog for the Dallas exhibition. Wong’s intake of art was omnivorous, and what he consumed would later be expressed in his paintings. Some of his early work resembles the 17th-century ink-brush paintings of Bada Shanren. His thickly layered repeated dots and patterning allude to Gustav Klimt and Yayoi Kusama. An untitled painting reinterprets Henri Matisse’s Landscape at Collioure, and several of his interiors evoke Vincent van Gogh’s Bedroom in Arles.

The Long Way Home, 2015, oil on canvas

One of Wong’s poems includes the lines,

Imagine reading a novel

Where instead of looking at the words

Your gaze was fixed on the spaces

Between them. When you get to the end,

What would you say of what you saw and felt?

Working abstractly with absence, paint that was scraped away, and even sections of unpainted canvas, Wong experimented and learned. If a painting didn’t feel right, he’d paint over it later. Wong told a friend that duende was never in his poems. But, he added, “I think it may have struck me one or two times in my paintings.”

Wong exhibited in Hong Kong, a new and robust art market—at the time, the third largest in the world. But Wong did not attract critical attention in Hong Kong or China. “Wong remained an outsider as a self-taught Hong Kong-Canadian,” Li writes.

In the early 2010s, he began communicating with other artists on Facebook. The online art community, Li told me, was “a sort of golden age. People asking questions, sharing their work, sharing their struggles, making connections.” Li says that the community included not only artists but also influential people in the art world. Through Facebook, Wong connected with gallerist John Cheim. The friendship led to another connection, this time with Matthew Higgs, who was curating a group show for Karma, a New York–based gallery. Higgs decided to include two of Wong’s paintings in the show, and eventually, Karma would represent the artist.

In 2016, Wong and his family moved to Edmonton. Wong had left many of his paintings in his Zhongshan studio, but that spring, humidity damaged much of this work. “This setback allowed him a reset,” Li writes, “and he completely immersed himself in figuration.”

In the months that followed, Wong began preparing for a solo show in New York. In 2017, he was diagnosed with autism. The same year, he also deleted his Facebook account. The images he’d shared, his contributions to threads, his private correspondence—all of it was erased. He created an Instagram account, but he most often posted images of other artists’ work rather than his own. He was no longer painting for the Internet; he was working toward his own place in the traditional art world. Here, then, is one meaningful way in which Wong diverges from Zinelli and his ilk. Dubuffet had described art brut as being by people who didn’t aspire to high art or didn’t want to sell their work in that context, people who had no need for “competition, acclaim, and social promotion.” For Wong, these things did matter.

“I’m technically an outsider artist,” Wong once wrote to Peter Shear, a friend and fellow painter. “Are you?”

Shear wrote back, “I never got my test results.”

“Just not very brut. lol,” Wong responded.

When Wong’s show opened at Karma in 2018, it was hailed as a huge success, with critic Jerry Saltz calling it “one of the most impressive solo New York debuts I’ve seen in a while.” Wong’s work was included in other shows, and some of it began to sell. It was around this time that the Dallas Museum of Art acquired The West.

See You on the Other Side, 2019, oil on canvas

In the weeks before his death in October 2019, Wong posted hundreds of screenshots on Instagram that, according to Li, represented a visual archive of how Wong’s mind worked—his intuitive approach to finding connections between images regardless of medium or time period. “Each screenshot,” Li writes,

presented two or more stacked Safari tabs that displayed an image from a Google search, which Wong excitedly called ‘a breakthrough’ and which reflected his own improvisational and fast-style approach to fashioning relationships and juxtapositions in his art. In some, the formal comparisons are obvious, such as a male model sporting a colorful floral jacket from the image search ‘louis vuitton spring summer 2019 runway’ with Matisse’s Joy of Life (1905) of a similar cheerful palette and with sinuous figures pulled up from a search for ‘matisse bonheur.’

Then Wong deleted his Instagram account. He left only his paintings.

After Wong’s death, his works were collected by MOMA, the Met, and other museums. The Art Gallery of Ontario held a major exhibition of his later works. Monita Wong, the artist’s mother, is chair of a foundation hoping to house Wong’s works in a new building in Edmonton that will also contain his studio—untouched since his death.

Jane Kallir writes that “the absorption of self-taught artists into the contemporary art scene also raises issues regarding appropriate standards of assessment.” Outsider artists esteemed authenticity of emotion and experience more than aesthetic value. “A lot of outsider art,” Roger Cardinal once said, “rotates around issues of personality, of asking who I am, which means going deep into the inner self of an individual.” For this reason, he suggested, scholarly consideration of outsider art could be “dangerous, provocative and damaging.” The old rubrics, moreover, benefited white men to such an extent that for Kallir, “the very notion of quality [had] become suspect.”

Kallir argues that the price of a work of art, rather than the assessment of an academic connoisseur, now determines its quality. “Savvy retailing on the part of the big auction houses and the global rise of the one percent have pumped up the value of certain artworks, turning them into branded status symbols and putative investment vehicles,” she writes.

In 2020, a small watercolor by Wong that was included in his 2018 Karma show sold at auction for $62,500. The same year, his painting The Realm of Appearances sold for $1.8 million, Shangri-La for $4.47 million. In 2022, The Night Watcher sold for almost $6 million.

The high prices have brought much-deserved attention to Wong’s work. But when I tell my husband about the spectacular price tags, he says, “Almost like NFTs,” which bothers me because the non-fungible tokens I have seen possess only speculative, and not aesthetic, value.

I can only hope that Wong, who shared so much of his art for free to anyone willing to scroll through it, would be pleased that it is now being sold at auction and hanging on museum walls. His work has arrived; it has made it to the inner sanctum of the art world.

“I do believe there is an inherent loneliness or melancholy to much of contemporary life,” Wong said in a 2018 interview, “and on a broader level, I feel my work speaks to this quality in addition to being a reflection of my thoughts, fascinations and impulses.” The art Wong made breaks rules and pushes boundaries. To his artistic process, he brought the whole of himself, but particularly his bright, humane, neurodivergent, achingly beautiful mind. Wong’s paintings were made in the pursuit of a pure creative experience—duende or something like it—even if he also wanted commercial success. Those who spend some time with his paintings, even just online, might sense a prickle on the back of the neck or a flutter of breath—fleeting experiences that Wong himself felt and then transmitted to us. We get to walk in his shoes, “register virtually everything … in terms of a painterly effect,” which allows us to feel our common humanity, no matter how different we are from one another. And if that isn’t the best way to value art, I don’t know what is.

The exhibit Matthew Wong: The Realm of Appearances will be on display at the Dallas Museum of Art from October 16, 2022, through February 19, 2023.