In 1999, writer Mark LaFlaur interviewed Jacques Barzun in connection with the publication the next year of Barzun’s book of history, From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Cultural Life, 1500 to the Present, which would become a best seller. The excerpts below from that interview are being published here for the first time. In our Spring 2019 issue, you can also read the lecture Barzun delivered half a century ago, “Present-Day Thoughts on the Quality of Life.”

The Effect of the First World War on Young Barzun’s Spirits

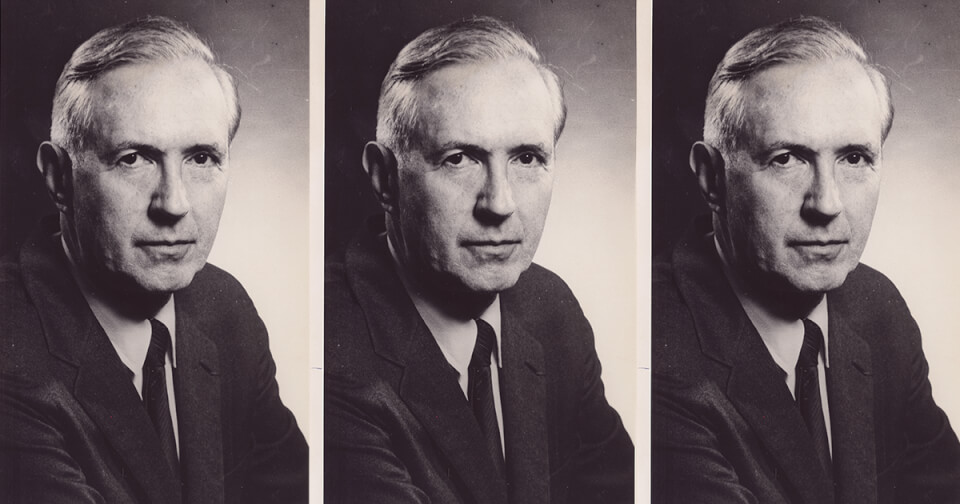

Barzun was born in France in 1907, moved to the United States for college in 1920, and lived out his long life in this country.

When I came to America I was rid of France, which had given me some very severe experiences. … The war really made me quite ill, physically and emotionally. I had to leave school and get a rest cure away from Paris, in Brittany, by the sea. … And the war ruined for good and all a childhood that had been very, very happy. I remember enjoying life as I never did afterwards. … Enjoying life in general, feeling bouncy and, like Erasmus, “what a joy it is to be living now,” or Wordsworth, “heaven to be alive.” That went in 1915. … Continual apprehensions of one kind or another, many of them artificial, but a child couldn’t know that. All this spy talk and having people accused of being spies, and slogans, and all kinds of nonsense. Too much official patriotism, women on the streets with a … receptacle for money, all the time, dressed in red, white, and blue. … And then at the school, we had part of the playground turned to a hospital, and crippled and amputated soldiers sitting in the sunshine in the spring—all sorts of horrid things for a child, and maybe for a grown-up too.

On His Education in the United States

Barzun’s father was a writer and government official who was sent briefly by Premier Clemenceau of France to the United States as a diplomat.

My father came over in 1917, during the war, on a mission … to explain the position of the Allies and the war aims and so forth. When I was ready for college, or nearly, he said that the French universities were not the place to go, for all the good people had been shot up and killed and so on. … He said, “And the postwar morale is and will be dreadful. Would you like to go to Oxford or Columbia?” …

And so my father arranged that in 1920 my mother and I would come here for my four years. … I thought I was going back to France to the diplomatic service, training for it. I decided to stay only when I was persuaded that I could not readily reinsert myself into my generation in France. I was 18, and by that time it’s too late to go into one of the great schools, as they’re called. A l’école supérieure or polytechnique, any of them, and it would have been foolish to try to catch up because the competition is such that you’ve got to be there pitching from the age of about 14. …

Then, when I came to like the life here, I thought I would go into the American diplomatic service, but in time I found out what the foreign service was like here, nothing like the French. Up to the time when I was making these decisions in the early 1920s, an ambassador in Europe was still a considerable person with great influence at home on public opinion and important in what happens to your country and other countries. …

I said, Well, I’ll go into the law in this country. I was persuaded out of it by two of my history teachers who said you really have a knack for narratives, description of events and people, and that is your real line. And so I was persuaded to go right on to graduate school.

On “Present-Day Thoughts on the Quality of Life”

Q: In this speech, you talked about how little has changed in the relation of people to people, and only superficial changes have come about since the 1870s.

A: The degree of change at any time has to be measured along different levels or layers of human life and activity. That is, you can notice a good deal of change, let’s say, in science. Or at certain times, like the present, a good deal of fairly rapid change between ordinary mail, email, and being entertained by movies which change every week at the local theater or the movies that change every hour on television, that sort of thing. Different rates, obviously. But then change in family life is much slower and it doesn’t change at the same rate all over.

Q: The speech ends on a generally positive note. You say that “the desire not just for life, mere life, but a special quality in life is planted deep …”

A: Oh, yes. It’s in the species, just as art is. You don’t have to have a school of arts for art to arise, since the cave drawings in southern France were not a product of the Beaux-Arts school in Paris. [laughs] … That’s why one doesn’t have to hang one’s head and say, “We’re decadent.”

On Decadence

Q: What meaning of decadence do you want readers to understand?

A: I want them first to believe what I say when I call it a falling off, which is a literal translation into English of the Latin derivative. Given that, the notion of what has fallen away must occur to the reader, and then, presumably, he has the material in this last chapter of the book and at various other points along the way. Loss of nerve, loss of intention, contradictory intention, that is, self-contradiction in the working of an institution, confusion, disarray, lack of originality, desperate means of looking “new” when actually very little is offered. Devotion to the words anti- and post- and so on—to somehow cover the facts that they feel need a new justification or rationalization. All these things must go under the idea of falling away from the path, or the efficiency, or the novelty. And as I say a couple of times, it ought to be looked on with calm and the knowledge that the worse it gets, the closer we are to renovation. …

Have you not noticed in the press, and I mean newspapers, many diverse references by many different people to what, now that we understand each other, would be called decadence in that particular realm or activity of modern life? … Morals, government, the press itself, which has been very self-critical lately, the several arts—so that one might say that putting all these testimonies together, we would have a collective statement that we’re in decadence.

A Sense of History

Q: What kind of sense of history, or appetite for history, would you like for readers to have, now and in years to come?

A: I think a good starting point for the ideal reader would be a lively interest in art and social thought, coupled with an interest in what is going on now in those two realms. So that with knowledge of past art and all the theories of government and society and philosophy and religion that such a person would have, curiosity would be aroused by the present situation in seeing how the past—other than what he knows—has led to the present state of affairs.

Q: You often use the word sympathy. Could you elaborate on that idea, about the sympathy that a historian must have?

A: You can’t understand anything unless you put yourself in the situation that you’re describing, or in the mind of the person who is prominent in the situation. That is, hostility gets you nowhere, because it only hits upon points of agreement or disagreement with your own system of ideas.