Rutgers University professor of Africana Studies and Human Ecology Naa Oyo Kwate received a Smithsonian Institution Fellowship to research and write a scholarly history of the origins of fast food in urban African-American neighborhoods. The following is an excerpt from her book.

On June 14, 1968, McDonald’s published, at what must have been considerable expense, a full-page, text-only ad in The New York Times and The Washington Post:

PLEASE! All concerned Americans. We have worked together to help build a great and wonderful country. Let’s not allow anyone—no matter how misguided or misinformed—to tear it down and destroy it. Let’s stick together and keep America great.

What did McDonald’s believe was putting America at risk? Whatever the threat, the ad’s rhetoric resonates today, after the 2016 election. McDonald’s enigmatic ad positioned the brand as a salve for readers’ deepest anxieties about the country’s future.

Fast-food restaurants boomed in the 1960s, with new franchises selling everything from hamburgers and fried chicken to roast beef, ravioli, and ribs. Almost without exception, McDonald’s and other fast-food companies sought white consumers. A 1966 Kentucky Fried Chicken full-page ad featured a tidy white family unequivocally enjoying their chicken dinner. In 1963, McDonald’s opened three drive-ins in Coral Hills, Maryland, which Ray Kroc described as “a solid, substantial family community, the kind of city which seems almost made to order for a McDonald’s restaurant.” For Kroc, seeking family-oriented customers meant careful investment in “the right kind of community,” he told a Washington Post reporter. In siting their restaurants and marketing their products, most fast-food companies left black communities off the map.

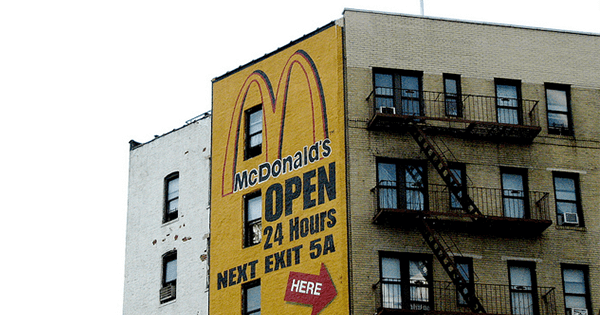

After studiously ignoring African-American communities in central cities for decades, fast-food chains began to see these spaces as great for business, crossing racial fault lines that fractured not only the restaurant industry, but the country as a whole. In recent years, public health research has found fast food to be disproportionately located in black urban neighborhoods. Today a concentration of fast-food restaurants signifies in common parlance a troubled neighborhood. Some cities, such as Los Angeles in 2008, have enacted legislation against fast-food chains, citing oversaturation and health risks. Fast food’s costs are often tabulated in obesity rates, but the risks extend beyond physical health. Much like stratification in housing, which shifted from market exclusion to market exploitation, fast food’s historical trajectory reveals a broader story about racial inequality in America.