The Rise and Fall of Adam and Eve by Stephen Greenblatt; Norton, 432 pp., $27.95

Most parts of the Bible have a historical, rhetorical, or poetic cast—often all three at once; they seek to explain things to the reader in more or less congenial terms. Even narratives like the Binding of Isaac in Genesis, the Book of Job, and the Book of Revelation, which pre-sent God’s purposes bafflingly or disturbingly, at least have happy endings to quiet the mind of the devout and the doubt-prone alike.

The story of Adam and Eve’s fall into sin, suffering, and mortality is different. It was probably borrowed and adapted by Jewish scholars from a foreign creation myth or myths during the Babylonian Exile, and is an awkward graft onto indigenous (or at least closer-to-indigenous) Hebrew literary traditions about patriarchs, warriors, kings, sages, heroes, and prophets.

After two Genesis chapters about the creation (and the text is plainly amalgamated, since humankind is shown to have been created twice), the single chapter about the fall comprises mostly simple action, dialogue at sharp cross-purposes, and God’s curse on humankind in four long verses. Nothing explains to a blunt inquirer why the tree of the knowledge of good and evil is the only one from which the nude, childlike couple are forbidden to eat. A verse about the divine fear of human encroachment—now equipped with knowledge, God says, “the man has become like one of us” and will eat from the tree of life and become immortal—doesn’t accord with the human-divine relationship as described elsewhere in the Bible, except perhaps in the story of the Tower of Babel.

But God didn’t contrive that challenge to his power himself. Why did he put the gorgeous tree with its delicious fruit in front of his most susceptible creations and leave them alone to their temptation? How could a just and merciful deity expect the man and woman to avoid the sin of disobedience when they have no knowledge of good and evil? Where does the conniving snake come from, and why? Why does it work through the woman first?

For the New Historicism, which stresses context over text, the reception of this tale is the ultimate playground. The less exegetes understood, the more they added, and the more they revealed of their own surroundings and preoccupations. Stephen Greenblatt, a leading New Historicist, offers a compelling account of Adam and Eve’s cultural antecedents and afterlives—especially the latter.

Learned rabbis gave the couple encyclopedic treatment. By one account, the original human was a hermaphrodite. A post-Edenic biography includes a second successful temptation—again, Eve proves weak; but now she cannot deter Adam from standing in the River Jordan as penance, after she abandons her own penance in the Tigris.

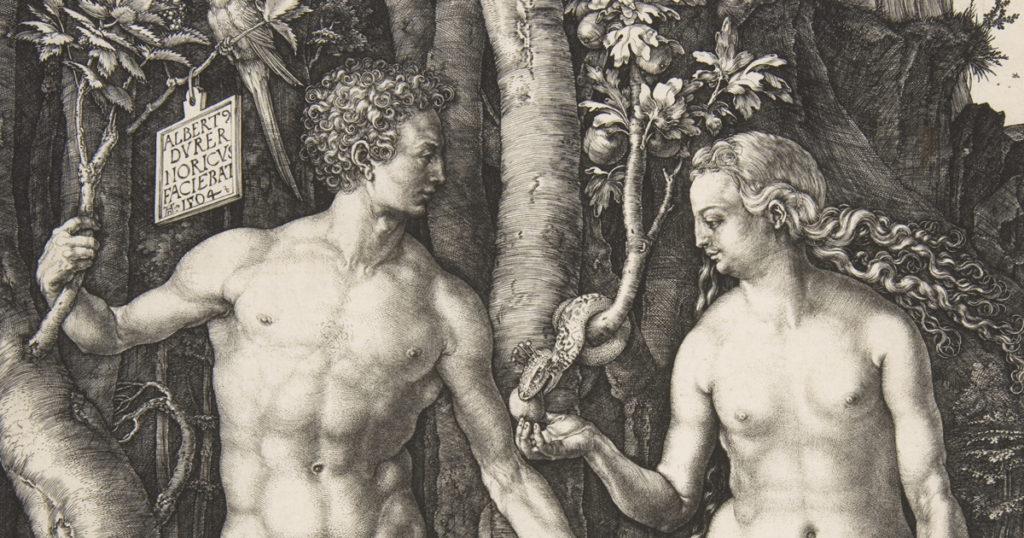

Greenblatt also explores the development of Christendom’s Adam and Eve imagery, from ghost-like signs of degradation and annihilation, to humanistic celebrations of physical beauty, and beyond. He shows how the story fed harrowing misogyny in the Church Fathers, medieval clerics, and early-modern witch hunters. The power of Genesis’s opening chapters in defining what humankind was and was for—purpose always inheres in an origin myth—pitted them directly against Darwin’s Descent of Man.

But one enormous personality, Augustine of Hippo (354–430), dominated interpretation for the longest period and so had a privileged effect on the way we in the West and in Western spheres of influence think of our species. His highly conflicted experiences of eroticism combined with his literary virtuosity to turn his personal reactions into pervasive theology and morality.

Augustine came up with the curious idea of “original sin”: Adam and Eve’s choice enslaved not only themselves but also all of their descendants, from the moment of their birth into death-ridden sin. And that sin was bound up with the curse of sexual desire, the unwilled drives of the human body that had tormented Augustine as a young man and trailed him into old age. Before the fall, the penis could be deployed for procreation as calmly and openly, and as obediently in God’s sight, as a hand could be extended for a good deed.

Such ideas about Eden, and the ideas’ implications, were not undermined significantly until Milton’s Paradise Lost—when a mirror-image life guided a reading of Genesis 3. Far from acceding to the early Christian cult of virginity after a “filthy” and “diseased” youth of sexual indulgence, Milton defied the louche Oxbridge mores of his time to remain chaste until a rather late marriage to a lively teenager. The marriage was an excruciating, scandalous failure at first but revived years later for pragmatic reasons to become at least sustainable and fertile. Milton was to have three wives in all, and enshrined marriage as hard work in a great poem: the erotic and companionable love of couples was fraught and permeated with tragedy, but it was a beautiful and inevitable part of God’s great purpose.

Greenblatt’s book spans millions of years, yet his analysis remains coherent. I read swiftly to the end, pushed along by a heady sense of discovery. (Disclosure: He draws upon my new translation of Augustine’s Confessions in his recent essay about Adam and Eve in The New Yorker, though not in his book.)

Greenblatt makes a trip to Africa to observe chimpanzee social behavior for clues about what the story of Eden means. He is shown, far out in the jungle, a polygamous community, with violent enforcement of norms underlying its idyllic leisure, and with characteristic “mate-guarding” by the dominant male. But later two members of the same troop, a female who had been under guard and a male recently deposed from leadership, brave the grounds of the research station itself in the hope of mating without interference. “Through violating the will of the supreme ruler and risking punishment,” Greenblatt writes, “they had become a couple.” Like Dürer’s iconic Adam and Eve etching, it is a riveting, instructive sight.