Sometimes I feel that Peter Matthiessen is the most underappreciated of recent American writers. I am biased, because he was my uncle and my godfather, but I think he should be mentioned in the same breath as Saul Bellow, William Styron, Philip Roth. The 20th-century version of the cultivated 19th-century adventurer, he brought back elegant accounts of the wild parts of every continent, including Antarctica. He is the only author to have won the National Book Award in both nonfiction (The Snow Leopard in 1980) and fiction (Shadow Country, 2008). His novel At Play in the Fields of the Lord was a finalist for the award in 1966, and so too was a nonfiction work, The Tree Where Man Was Born, in 1973.

Not just ambidextrous, Matthiessen stretched both forms of writing. After reading Under the Mountain Wall, his 1962 account of life in a New Guinea tribe, Truman Capote credited him with inventing what would be called the nonfiction novel, whereby fictional techniques shape narrative facts. Matthiessen’s experimental novel Far Tortuga, about a doomed voyage of turtle hunters, was his favorite of his 30-odd books. Among other conceits, it eschewed the use of adverbs and adjectives. When Far Tortuga was published in 1975, the poet and novelist James Dickey told him he had changed American literature.

Not quite. When Matthiessen died in 2014, the obituaries were full of praise, but they didn’t say he had changed our literature. Since he was raised not to toot his own horn, Peter would not have complained. Still, he observed more than once that, in dividing his work between fiction and nonfiction, he had made the assessment of his literary achievement more difficult.

My uncle was a hard man to get a hold of, in more ways than one. Reserved and self- deprecating on the outside, he was jumpy and hotheaded on the inside. If you stood next to him, you could sense the unquenched embers of the young rebel. His politics were uncompromisingly left wing, another impediment, perhaps, to fully appreciating him. His ardent defenses of endangered species, endangered fishermen, Latino farmworkers, Native Americans, and others were modulated by an ironic, elegiac tone, which deepened as he grew older. Peter’s literary voice and also his speaking voice, magnetic and low in his chest, were resonant of Zen Buddhism, a practice he adopted in his early 40s. Although “mindfulness” seems to be on everyone’s lips today, a generation ago a picaresque writer who averred Buddhist restraint was a peculiar persona to understand.

He wouldn’t have liked my use of picaresque, but I’m thinking of the episode that—to his irritation and chagrin—he became most known for, having nothing to do with his writing. As a young man, Peter had worked for the CIA in Paris. His job at the newly founded Paris Review was his cover for the agency. He gave up the secret assignment after a short time, but the revelation of it, decades later, caused him a lot of trouble.

A few years before his death, Peter began to put together materials for a memoir. When he realized he would not be able to outpace his cancer, he relabeled the notes as sources for a potential biographer. A full-blown biographical treatment may or may not happen. As his admiring nephew and godson, and a writer myself, I asked Peter’s executors if I might have the first crack at the notes and sketches on his computer, not for producing a book but rather an essay about my uncle and the Matthiessen family.

Quickly I saw a way to proceed. Deeper than Zen and yet connected to it was Peter’s love for nature, unbridled nature, soothing him through his 86 years. The feeling had begun during his boyhood on Fishers Island, New York, where my grandparents spent their summers and falls. Fishers—he described it in the notes as a seven-mile ridge of hills and bluffs, deciduous woods and fresh-water ponds—lies just off the coast of Connecticut. This broken coast and offshore islets, with their many coves and tide pools, was where I was taught to swim and fish and handle small boats, and where a lifelong fascination with wild birds and marine life had its start.

Fishers Island, barely disguised, is the setting of Race Rock, Peter’s first novel, and is not far from his longtime home on the eastern tip of Long Island. Published in 1954, Race Rock is a tyro’s book, and touchingly autobiographical. The central character, George McConville, is an unhappy young man from a wealthy family who reunites with childhood companions at the family estate on the New England coast. While a hurricane slowly approaches, they drink, shoot ducks, and drink some more:

George felt unbearably oppressed. Yet he knew there was nothing unbearable in his life … and the guilty paradox of his existence angered him. He had money and friends and position. … the thick slow fuse of anger curled round and round like a tapeworm in his rebellious gut.

Fishers Island represented “money and friends and position.” In fact, its beauty could not have been maintained without the rich. The island fostered and harbored the two main preoccupations of Peter’s life—the natural world and its creatures, whose graceful movements so gratified him, cheek by jowl with affluence and far-reaching economic power, which he began to see as enemies of nature. Since it was too late now to ask Peter about the importance of Fishers, my idea for the essay was to set his notes about his youth next to my own memories and to view the island stereoscopically, if that could be done.

Born in New York City on May 22, 1927, Peter was brought to Fishers for the first time when he was just two weeks old. From the notes:

Our house, airy white and driftwood gray, was designed for his new family by a young New York architect named Erard Matthiessen. At the time of my arrival, pamper fresh (so to speak) from the Leroy [Hospital], his family was comprised of a known beauty, his wife Betty, née Elizabeth Carey, and little Miss Mary Seymour M., age 18 months.

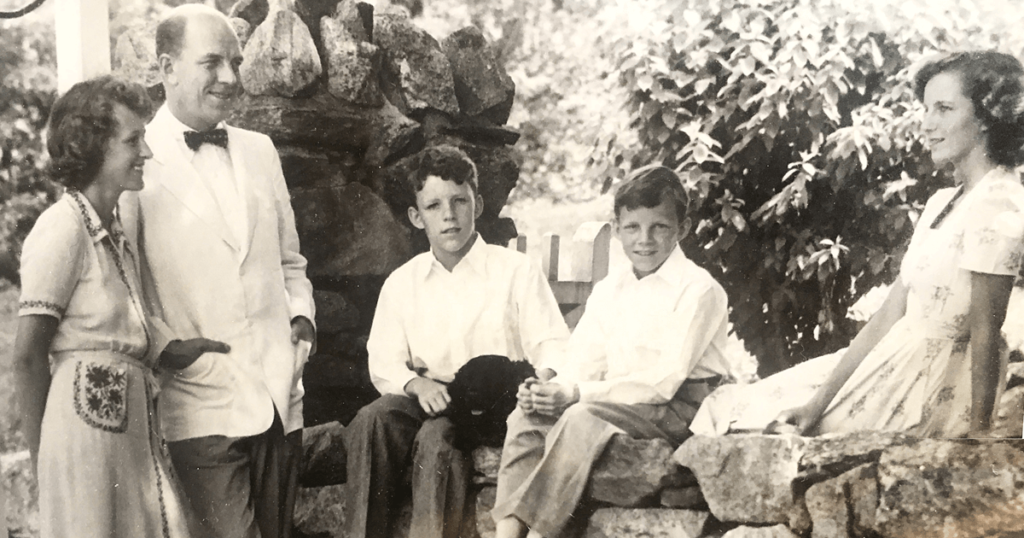

Mary is my mother. Throughout my uncle’s life, I could always calculate his age because my birth came 20 years after his almost to the day. A third and final Matthiessen child, George Carey, was born on Fishers Island 14 months after Peter. Although my mother stopped using Seymour and Carey never used George, Peter could be only Peter, since for some reason he had no middle name. As for my grandfather, Erard Adolph, he strongly disliked his two given names and went through life as Matty.

Of Nordic ancestry, the Matthiessens had migrated to the United States from Germany in the middle of the 19th century. Four brothers became rich industrialists in the Midwest; their primary businesses were zinc mining and processing, clock manufacture, and sugar refining. Matty’s father and mother were first cousins, so when they married, the family having gravitated to New York, two fortunes were consolidated. My grandfather went to The Hotchkiss School, Yale College, and Columbia School of Architecture knowing that he did not have to work. He practiced as an architect until easing into retirement around the age of 45.

By contrast, my grandmother came from a well-to-do Virginia family that had fallen on hard times. She had kept up all the Careys’ social graces, however, and Matty provided the means to clothe and exercise them. Moving with the seasons from Park Avenue to Fishers Island to Florida, Betty and Matty Matthiessen made an impressive pair: she demure, arch, and quietly humorous, he witty, outgoing, and outdoorsy.

In the sketches of his youth, Peter focuses predominantly on his father. He introduces him as admirers saw Matty, a man’s man, handy with boats, power tools, and shotguns, as deft on the dance floor as he was on the golf course. My grandfather was only 23 when he designed and built his house on Fishers Island. Although already a summer resort, Fishers in the 1920s was frequented only at its western end. E. A. Matthiessen was one of about five dozen partners in the development of the bulk of the island. The properties were large, many with their own ponds and beachfronts. According to Pierce Rafferty, the island historian, “Even today, more than 85 years later, there are only about 200 houses in the private East End section.”

Fishers hardly changed between my uncle’s summers during the 1930s—in the darkest days of the great Depression, our well-insulated family maintained a summer house on Fishers Island—and my own childhood visits a generation later. What would the place be like today? Last October, I boarded the early ferry from New London, Connecticut, for the 40-minute ride across Fishers Island Sound. The sparkling air was cold. On the ocean, terns and laughing gulls fluttered and flashed at the baitfish that bigger fish were, no doubt, chasing to the surface. I went inside to the warmth of the cabin. Prior ferry trips, which had dwindled to 10 and 15 years apart, had made me uncomfortable, as if I were channeling Peter, put off by the prospect of perky women in Swiss- patterned sweaters and their blond, lantern-jawed husbands in lime-green pants.

Peter would have approved of the incongruous scene this morning. Wearing hoodies, black and brown high school students from the city of New London commuted to the magnet school on the island. It was an unusual arrangement between school districts in Connecticut and New York, I was told, and probably would not have been sanctioned in the old days. The ferry, preceded by a blast of its horn, sidled up to the weathered pilings of the dock. According to Rafferty, the year-round residents of the island, who still cluster about the west end, number some 230 people. The additional summer population is more than 2,000 and no longer includes any Matthiessens.

My grandfather used to berth his boats in a cove nearby. Matty did not go in for sailboats. I remember zippy Boston whalers for near-shore fishing and yachts with throbbing engines shouldering the swells aside. His large, sun-mottled hand rested easily on the helm near a gleaming can of Schlitz or Miller. But my fishing adventures with “Pa” were minor compared with Peter’s:

I was not yet ten when he first took me deep sea fishing … miles across Block Island Sound to Montauk Light at the tip of the South Fork, then southwestward on the open ocean trolling for yellowfin tuna and ever in hopes that we might harpoon a swordfish, which in those days still lived long enough to become enormous and appear within a few miles of that coast.

I’d arranged to hire a boat to take me out to Race Rock, a real place. The Race is a shallow ledge whose menace to ships was defanged by a lighthouse built upon it in the 1870s. Ever since the light keeper left, yielding to automation, the empty rooms are said to be haunted, and cormorants squat rudely on the solar panels of the steeply gabled, corrugated roof. At this hour, the water around the lighthouse was merely ruffled, but there was an odd look to the ruffle, the whitecaps jostling and breaking along a line of smooth water that indicated treacherous currents. The Race—that jagged meeting ground of current and broken tide—is where the water in Long Island Sound spills from its glacier-carved basin into the depths of the Atlantic, and where it rushes back hours later on the returning tide.

Peter first saw the Race with his father: I observed with dread the relentless shifting of dark muscled waters. … The sheer might of this current … had such a grip on my imagination that I named my first novel after the Race Rock lighthouse for no better reason than its evocation of the fathomless power of existence. The Race was also a good place to cast for bluefish in my youth. The bluefish prey on small menhaden, which are caught in the rips, confused. The Race was forever in a state of change, and its faces were gray and blue and black, and red with torn menhaden when the bluefish ran, and scarred with white.

A border water, a no man’s land, the Race lay between Fishers Island and the unruly wider world. Longing for adventure, the boy would need courage to get across that line. Later, visiting from his home on eastern Long Island, Peter would cross the Race in his own boat. He would try to scoot through on a slack tide, though all bets were off in foul weather or wind. On one of these trips, a loose cable gave way and his brother, Carey, fell overboard, smashing his head as he fell. Peter recalled the accident in anguished detail. Oh my God. Please, Carey, wait! In the cold silent water swathed in fog, there was no sign of him. I peered and shouted. When Carey bobbed up at last, Peter hauled him violently aboard. His best friend in the world had nearly died in the Race.

Fishers is at most a mile wide, and in many parts narrower, like a corkscrewing marine worm. All that bright fall day, whenever I turned toward the sun, the sea would explode with reflection, white particles bursting on blue, as if a pointillist were attempting to blind me. I drove past the Hay Harbor golf course toward the heart of the island, the guard on the one road waving me through on the assurance of my old connections. For years my grandfather and uncles owned the large, brackish Island Pond, where Carey, a marine biologist, cultured juvenile oysters for commercial growers. Protruding into the pond is a lovely eight-acre peninsula. The Matthiessens donated it for a nature sanctuary in the name of my grandmother after her death in 1977. Matty’s project in old age was to cut circuitous, interlocking trails through the beeches and scrubby oaks overlain by Virginia creeper.

As I strolled within this mini-wilderness, I felt for the first time the almost comical smallness of Fishers. Yet my grandfather must have felt secure and happy on this tidy island, protected by its moat of ocean. For, truth to tell, the Matty inside the charming man’s man had endured a lonely childhood supervised by chilly Germanic parents who disliked each other deeply. Inheritance aside, Matty was not much equipped for the rough and tumble of the world, and he communicated his anxiety about competing in life’s bigger race to his restless son. In short, he undercut Peter. Subtly, Matty disapproved of Peter’s ambition to win a place for himself in American letters. That’s not stated in the notes. I know this from observing the two, and because my grandfather, I think with good intentions—maybe it was just prudence—doubted plans of mine, too.

Paternal approval, when and where it came, was an elixir. For example, in the family hobby of birding. Although my grandparents were always interested in birds and nature, Peter wondered, looking back, whether his father had become an expert birder and a champion of conservation in part because of his son’s blooming obsession. Peter kept pigeons at their winter residence in Connecticut, and one summer he trained a “genius gull” on Fishers. The boy drew up lists of wildlife sightings of all kinds. When I saw my first swallow-tailed kite hawking back and forth over the Tamiami Trail [a highway in Florida], I almost caused a car wreck. I jumped out, I couldn’t stop yelling; they couldn’t get me back into the car! He doesn’t mention Matty’s enthusiasm, but I remember being about the same age in Florida when, with heavy, borrowed field glasses, I spotted a black-necked stilt in a line of ordinary shorebirds. My grandfather, swiveling his binoculars upon this uncommon find, doused me with praise. I drank it up. I felt like a million dollars.

Nobody’s childhood is perfect, not my grandfather’s, not my uncle’s. The most important variable is one’s inborn nature, which is like a wild card drawn from a genetic deck. Life launches a unique biological and behavioral package, after which parents, let’s say Betty and Matty Matthiessen, conduct a nature-nurture experiment. As in a proper experiment, the three sun-baked children, Mary, Peter, and Carey, at the beach and tennis court, are treated just the same. But do they become the same? No, their different natures take control.

Thus Mary was forthright, glittering, and sociable, and Carey genial, athletic, and popular, both well within the family program, while Peter was—I switch to his own telling—temperamental, too sensitive, scrawny, a dreamer, embarrassed to need glasses, ashamed of having to wear aluminum mitts at night because he sucked his thumb. Threw up from nerves during assembly at Greenwich Country Day School. Afraid of being taken for a sissy. Churlish as a boarding student at Hotchkiss. During teenage summers, a spoiled carouser. Really, just impossible. My mother says Peter exaggerates, but allows he was “the difficult one,” and sometimes she’ll add “the tortured one.”

When Peter learned what the Social Register was, he demanded that his parents remove his name from this snooty catalog of moneyed New York families. Volunteering one summer at an inner-city camp, he was appalled and angry that children about his own age could be so hungry. On their first day at the camp, the kids had sat down to a welcoming meal and gorged themselves until they got sick. When Peter related this story later to interviewers, he did not credit my fairly liberal grandparents for at least exposing him to the other side. Everything came to a head after his prep school graduation in 1945, which he’d refused to attend. My grandmother was beside herself. Matty told Peter to leave the house, a punishment that he felt he more than deserved. Not just anger, mean tongue, sullen nature but insolence, disobedience, drinking, speeding tickets, hound dog dirty attitude to go with it.

The evil climate of World War II had a lot to do with his difficulties. In the summer of 1944, just 17, he had joined the Coast Guard without telling his parents. Matty found out where he was and sent him back to Hotchkiss. In 1945, he joined the Navy but too late for combat. He was back in New York, on his own, in late 1946. Brooding, lonely, angry, aching for faraway destinations with romantic longings for unfettered “real life,” I had developed a small drinking problem and an obdurate depression. Briefly he saw a psychologist. It was probably his lowest point. In 1947, he resumed his education at Yale, which surely steadied him, and also resumed his partying, which probably didn’t. A professor scolded him that he should have won the top literary prize. He got a concussion barreling down a ski slope. He became an uncle and godfather for the first time.

Peter’s first cousin once removed was F. O. Matthiessen, the prominent literary critic at Harvard. F. O. and Matty had been friends since their time in New Haven together. F. O.’s father, Frederick William Jr, known in the family as “Wild Bill,” was my grandmother’s scapegrace brother, as well as the survivor of every sort of moving accident and was still pursued by angry husbands up and down the land. F. O.’s relationship with his hypermasculine father was like a bad caricature of the tension between Peter and Matty. Wild Bill rejected his cultured son, who was gay. That sissy, he called him. Told that his son was the great authority on the Jameses, Wild Bill thought it must be Jesse and Frank James, not Henry and William. In 1950, F. O. Matthiessen set his Skull and Bones key on a window ledge and jumped out of a 12-story hotel room in Boston. It was the second family suicide to rattle Peter. His maternal grandfather, sweet-natured “Pop” Carey, had killed himself before the war.

It’s hard for me to square the agitated figure I was too young to know with the Zen-tinctured literary star of my grown-up years. Peter’s biographical notes offer little more than bullet points or mnemonic phrases about his life and career after the 1950s. More interested in his youth, he composes scenes in a mordant minor key that resolves unexpectedly into major chords, as when he reconsiders Fishers:

Because altogether, my childhood was not bad at all. I have the content feeling of many sun-filled summers, romantic gold-brown autumns, impressions, memories. The sounds and odors and queer lights at evening are baked in, the sea wrack on white sand, and the cold ocean swimming from the island’s south beaches, body-surfing small waves coming fresh from the Atlantic through the broad reach between Block Island and Montauk Point … and in years to come, surf-casting from rock points for striped bass and autumn gunning for wild pheasants, walking them up [jump shooting] or over [pointing] springer spaniels, not infrequently interrupted by a passion, everywhere and increasingly, for intensive birding.

My grandparents’ house is on a bluff on the north side of the island, facing Connecticut and Rhode Island. The present owners, who were not at home during my visit, permitted me to go down to our little cove and beach, the place most “baked in” with Matthiessen memories. Here twin downhill paths enclosing half-buried lichened glacial boulders and blackberry and myrtle thicket ended in stone steps descending to a shallow crescent of white sandy beach. Although boulders and thickets have given way to smooth lawn, the beach itself is the same. I sat on a driftwood log for a long time. Here Peter and his siblings, and I and my siblings, would dig down through the sand until we got to clay. We would scoop it out and fashion all sorts of objects, and the sun, like a family servant, would cure them without being asked. Here, when his castle’s moat would not fill with water—just the opposite—little Peter discovered the motion of tides. I saw my elegant grandmother once again put on her white bathing cap, the kind embossed with a floral pattern, and take her morning swim, once more her light, practiced strokes moving straight away from me into the lambent Fishers Island Sound. And here too I investigated an acquired memory, the main reason I come back. I wanted to revisit the scene of the “green-blue water” incident, the seminal incident, my uncle says, of his childhood.

Peter reviewed the incident at least half a dozen times before his death, altering details here and there, as he made the story darker and richer. A confrontation with Matty took place just beyond the rocky enclosure of the cove:

Beyond, clear water six to ten feet deep over white sand—the “green water”—extends perhaps forty yards offshore to where clear sand gives way to dark rocky bottom and the “blue water” of Fishers Island Sound. That border filled me with dread—not the deep water but those shadowy indistinct boulders, dark amorphous shapes shrouded by algaes, scarcely visible below the boat, yet discernible enough to persuade child or fool that those big shapes were shifting, changing places, slowly moving, and that those strange fronds straining toward the surface—toward defenseless children, in effect—might well conceal gigantic crabs and savage moray eels and monsters heretofore unknown to science.

Peter seems uncertain of his own age, whether he’s six or eight or nine. Matty has brought him, Carey, and my mother out in the boat to see how well they can swim. The kids have been taking swimming lessons this summer. Matty tells them to jump in—Mary and Carey do so eagerly, and paddle around. Eyeing the green-blue discontinuity by the anchor line, Peter refuses to go, though he’s a capable swimmer and diver. I already knew my phobia was unreasonable and felt humiliated because I had not outgrown it. My sister, vexed by the delay, pronounced me silly and my little brother looked away, made anxious by the confrontation.

Matty loses patience and picks up Peter and throws him over. The frightened boy grabs his father’s shirt, and as a result bangs his arm hard on the side of the boat. Coming gasping to the surface, he shoots a curse at his father, either bastard or son-of-a-bitch, neither believed to have been in his vocabulary and verboten at any age. The four Matthiessens go home in shocked silence. Peter is sent to his room, his arm throbbing. The worst part is that his mother, instead of comforting him, as he imagines she will do when she hears what happened, sticks her head in and says, We are so dreadfully ashamed of you. She closes the door. Peter writes that his alienation from his parents began then and never recovered fully. Even decades afterward, his arm would start to throb during moments of stress.

His notes make my grandparents look bad, but he makes himself seem worse, the viper child in full agreement with Matty that day on the boat when he cast me from his sight. Why did he feel that way? Was Peter’s reportorial daring in Africa, the Amazon, or the Himalayas, expedition after expedition, about nothing more than measuring up to his father?

My uncle and I never spent much time together, and for that and other reasons we were not particularly close. But there was one time we were. It was 1969, and I was just out of college, hanging around San Francisco while I fenced with my draft board back home. He was 42 and was putting the final touches on Sal Si Puedes, his book about the farmworker leader Cesar Chavez. Peter invited me to visit him at the motel where he was staying in Fresno. We had dinner, smoked some pot. (My siblings and I still refer to him as Pete Pot, our hip uncle.) He told me that the thing he had learned about fear was to face it—and not just to face it but to go directly into its maw. In hindsight, I think it was the lesson he’d drawn from the green-blue water incident. The next morning, he gave me directions to a field and said goodbye. Alone, I drove over there and saw many farmworkers breaking their backs in the hot sun. Peter had urged me to think about them, and I have. Peter thought that Chavez, a man of the earth, was the most admirable man he had ever known.

Living across the country, I rarely saw Peter in later years. My grandfather’s burial on Fishers, in 2000, marks the last time I was alone with him. He and I were walking together, from nowhere far to somewhere near. The way was wooded, lightly wooded. As he was talking, I heard a bird insistently call. Its rolling, almost metallic song seemed too powerful for Fishers Island. Its song could hardly be contained.

Since it is fine in our family to interrupt anyone on account of a bird, and since in fact I was rusty on my eastern species, I broke in.

“Peter, what’s that bird?” He stopped, and we listened together. I wanted him to be proud of me.

“It’s a Carolina wren,” he said.