Freedom Tales

Long before the contentious school board fights of today, Lydia Maria Child tried to help America’s children understand their country’s racial transgressions

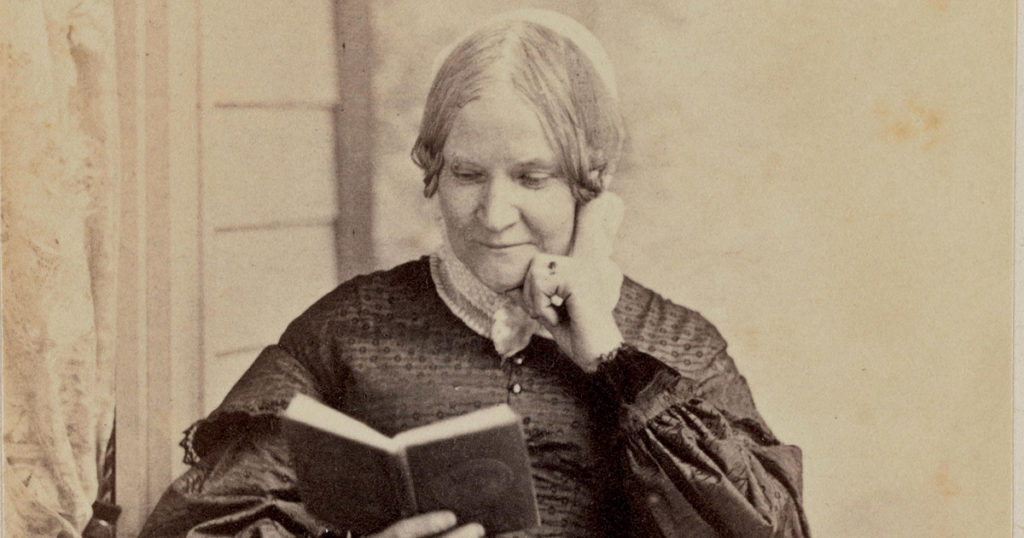

In 1825, Lydia Maria Francis was only 23 years old, but she had already written two novels that had made her a literary celebrity. She was fiercely proud of her country’s new history and bright promise, and her protagonists exhibited all the virtues Americans confidently claimed. They were principled, independent, and unbiased. They were also fair, just, and honest. Her first novel, Hobomok, caused a small sensation. “I should think more highly of the talent of the woman who could write ‘Hobomok,’ ” one admirer gushed, “than of any other American woman who has ever written.” The second, The Rebels, was set in Revolutionary War Boston and included an imagined speech by the American patriot James Otis that was so rousing that schoolchildren began memorizing it and attributing it to Otis himself. These early successes catapulted Francis from her working-class origins as a baker’s daughter into the glittering social circles of Boston’s literary elite.

Soon it became clear that Francis had talent as a children’s author as well. In 1824, she published Evenings in New England, a collection of stories, fables, and riddles for young readers. But Evenings was more than entertainment. It aimed to answer some critical questions. What kind of virtues did the new country need? What kind of stories should shape the character of its children? What, in short, should American children be like? Francis populated her book with both glorious heroes of the Revolution and simple, honest characters from Maine. Her stories guaranteed young readers that honesty, ingenuity, and integrity were their birthright, characteristic of every American from the local farmer to George Washington. The overall message was clear: American children should treasure the ideals of freedom and equality they had inherited and pass them on.

But if American children were to be schooled in basic lessons of fairness, honesty, and justice, some awkward facts needed explaining—namely, that Black humans were being enslaved and Native Americans were being removed. How to explain this to children who were also being told that their country was founded on freedom and equality? Maria Francis had always been direct and headstrong. By page three of Evenings in New England, she had named both issues. In subsequent chapters, she confronted them explicitly.

In the story “Indian Tribes,” a young protagonist named Robert asks his Aunt Maria a simple question: Where have all the Indians gone? Aunt Maria gives a sober reply. These “numerous, brave, and generous people” have almost become extinct. “But what right had we to take away their lands?” Robert wants to know. We didn’t take them, his aunt replies: “In most instances” they sold their land willingly—although, she admits, “it is to be feared they are too often cruelly imposed upon.” Robert keeps up his interrogation. Why would America’s president allow such cruelty? Well, Aunt Maria suggests, the president means well, but sometimes his subordinates behave badly. This bad behavior, she regrets, often produces violent results: “Exasperated by these insults, the injured tribe will often go to war with our people, while we, ignorant of what they suffer, complain of them as a nation in whom we can put no trust.” It is true that Native warriors are sometimes called bloodthirsty, Aunt Maria concedes to her nephew, but they are, quite simply, fighting in self-defense. “How I do wish something could be done to make all the Indians as happy and prosperous as we are,” Robert concludes. “It is indeed desirable,” agrees Aunt Maria, but probably not worth much effort: “it is probable that in the course of a few hundred years, they will cease to exist as a distinct people.”

So much for those who were being forced to leave. As to those who had been forced to arrive, she addressed their situation in a story ominously called “The Little Master and His Little Slave.” Here again is Robert, this time venting his youthful fury on the South. “It seems to me,” he declares to his aunt, that “the people at the southward must be very cruel, or they would not keep slaves as they do.” This outburst earns him a stern rebuke. “Your opinion is very unjust, my child,” Aunt Maria begins. True, slavery is an “indelible stain” on the country. “But it is not right to conclude that our southern brethren have not as good feelings as ourselves”; in fact, she informs him, “no part of our country is more rich in overflowing kindness and genuine hospitality” than the South.

To illustrate her point, Aunt Maria recounts a story about little Ned, an incorrigibly unruly enslaved boy whose misbehavior, by the author’s telling, has finally earned him the whipping he deserves. But just as he is tied to a tree and the overseer raises his arm to strike the first blow, the master’s son Edward, frantic with sympathy, throws himself between the Black boy’s naked back and the whip. Edward’s father arrives, surveys this disorderly scene, and declares that Ned is a hopeless case and must be sold. Edward pleads to be allowed to keep and try to reform Ned. His wish is granted, the reformation succeeds, and a grateful Ned grows up to be Edward’s most trusted body servant.

Despite this touching denouement, Robert is unconvinced. “I cannot bear the idea of keeping slaves,” he confesses to Aunt Maria. “I am very glad you cannot,” she commends him. She admits that slavery is the “greatest evil that we have to complain of in this happy country.” But even great evils, she counsels, do not demand immediate solutions. “I have already told you, that it is dangerous to cure some kinds of sickness too suddenly,” she tells her nephew. “It is so with slavery.” It was better to wait and, in the meantime, never to forget “that our Southern brethren have an abundance of kind and generous feeling.” Surely, since there “is so much to admire and love in their characters,” they will soon emancipate all their slaves themselves.

Such comforting arguments could allow well-meaning white Americans to live their lives with clean consciences. Violence against Native Americans was regrettable, but they were destined for extinction anyway. Slavery was unfortunate, but the genteel sensibilities of southerners guaranteed that it, too, would soon fade away. As to any accounts of cruelty, they were probably exaggerated, and certainly unfair to the good and generous people in the South. Insofar as enslaved people were punished, the punishment was probably deserved. Most important was to avoid any radical agitating that would interrupt historical progress or upset the delicate political compromises that had kept North and South, so far, united.

Evenings in New England was so successful that a publisher prevailed on Francis to launch The Juvenile Miscellany, a periodical for children, in 1826. The first of its kind in the country, it, too, caused a sensation. “No child who read the Juvenile Miscellany … will ever forget the excitement that the appearance of each number caused,” one reader remembered decades later. By New Year’s Day 1827, it had a circulation of 850, with more subscriptions coming in every day.

The Juvenile Miscellany often included stories that encouraged sympathy for Native Americans. But about slavery the Miscellany was silent: there were no stories, no dialogues, no poems or essays to remind young readers of what life was like for enslaved children in the South. The only evidence that slavery existed was in an account of a northern traveler’s visit to Baltimore. “It cannot be too much regretted that such a thing as slavery exists,” the traveler admits after witnessing evidence of the institution, “but so far as concerns the actual situation of slaves at the South, I think New England prejudices have been violent and unreasonable.” The real problem was not slavery but agitators in the North who insisted on revealing ugly facts and whose prejudices against slavery were unreasonable. The Miscellany’s editor shared this conviction, so she passed it on to her young readers. But this calm counsel was about to be retracted as, in the next few years, the beloved Miss Lydia Maria Francis transitioned into the notorious Mrs. Lydia Maria Child.

In 1828, Francis married David Lee Child, a journalist, lawyer, and strong opponent of slavery. Enslavers were violating every core American principle, he argued in his Massachusetts Journal, and deserved whatever infamy they received. His new wife was skeptical, but she was listening. Shortly after their wedding, Andrew Jackson was elected president and began his campaign to eliminate Native Americans in the South who stood in the way of those determined to expand both cotton production and slavery. David covered the ensuing outrages in his newspaper. He also argued in print that Native Americans had a right to defend themselves, even calling for white Americans “to take arms to protect the Indians and to preserve public treaties inviolate.”

In the years after meeting and marrying her husband, the Miscellany’s editor began to shift her position. Between 1827 and 1829, the new Mrs. Child published five short stories with Native American themes that show a sharpening, if imperfect, sense that she had not done them justice in her earlier publications. And then, in 1829, she published a book called The First Settlers of New-England: Or, Conquest of the Pequods, Narragansets and Pokanokets: As Related by a Mother to Her Children. This time the topic was European settlers’ treatment of Native peoples, and Child, through an exacting history delivered by a fictional mother to her daughters, spares no detail of European cruelty and treachery. Like Robert, the little girls are aghast at the betrayals and atrocities. “Oh! mother,” little Caroline exclaims after one particularly horrific example of violence, “it appears impossible that human beings could have been so altogether lost to the feelings of humanity, or that they could have been so grossly deceived as to imagine themselves entitled to the name of Christians.” Unlike in Child’s earlier stories, the mother does not rebuke her daughters for doubting their fellow citizens’ sympathies or assure them of their president’s good intentions. She instead praises their indignation and confirms their worst suspicions.

At the end of the dialogue, the mother steers her daughters firmly from history to the present, showing in the process just how completely Child had reversed her position. “It is, in my opinion, decidedly wrong, to speak of the removal, or extinction of the Indians as inevitable,” she concluded, just as President Jackson was doing exactly that. “I devoutly trust, that our Government will not again pusillanimously compromise with the sordid avaricious Georgians,” she wrote of the southerners whose generosity she had only recently praised. “The crisis admits of no delay,” she urged. She also deplored the Jackson administration’s resolve to drive the Seminole out of Florida. “[I]f the Seminoles be not speedily relieved,” she predicted, “they must perish in the swamps to which they have been driven, in the presence of a civilized [C]hristian people, who have solemnly pledged themselves to be their guardians and protectors.”

Child published but did not promote The First Settlers. The book was clearly written in the heat of indignation by someone whose faith in her country had been badly shaken: perhaps its author was alarmed at her own outrage. The moral paranoia is palpable. If, contrary to what she had urged her small readers in Evenings in New England, American actions could not be excused by good intentions or redeemed by historical progress, what else might she have been wrong about? If she had been so blinded to the moral weight of atrocities against Native Americans, what else might she have missed?

The following year, Child met the fire-breathing abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and converted to abolitionism. To be an abolitionist in Boston in the 1830s was to be a radical. Politicians and religious leaders warned that such fanatics would destroy America’s unity, undermine its religion, and wreck its economy. But given her new skepticism and armed with new facts, Child was undeterred. She had already dedicated her life to the question of what it meant to be an American. Now she was sure. It meant pledging every resource you had to compelling the United States to live up to its founding assertion that all humans were equal. Patriotism demanded that all Americans sacrifice what they had to achieve this goal.

Child quickly settled on what she had to offer the movement: her reputation as a popular novelist and children’s author. Three years after her conversion to abolitionism, Child published a book assailing the evils of slavery. In her introduction to An Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans (1833), she anticipated her readers’ outrage: “Reader, I beseech you not to throw down this volume as soon as you have glanced at the title.” She was still, she reminded them, the trusted editor of The Juvenile Miscellany. “If I have the most trifling claims upon your good will, for an hour’s amusement to yourself, or benefit to your children,” she wrote, “read it for my sake.” She offered her readers one more enticement. “Read it,” she wrote, “from sheer curiosity to see what a woman (who had much better attend to her household concerns) will say upon such a subject.”

What followed was a methodical denunciation of the history, politics, economics, and moral justification of slavery. Child carefully took apart the arguments she herself had once used to defend the institution while providing harrowing accounts of torture and mutilation—enslaved men trying to escape who were torn apart by dogs, enslaved mothers driven to insanity as their children were sold away. She laid responsibility for slavery at the feet of northerners whose prejudices and willingness to compromise with the South made them complicit in this wickedness. Where in all this, Child demanded to know, were the virtues Americans claimed as their birthright? Where was America’s vaunted honesty if it shrouded its barbaric practices in patriotic platitudes? Where was its integrity if it egregiously betrayed its ideals? What kinds of citizens would the children of such a country, steeped in willful ignorance and self-serving dishonesty, become? The result, Child promised her readers, would be nothing less than the failure of democracy and the triumph of tyranny.

The backlash that followed was swift and brutal. Ministers warned against her, predicting “evil and ruin to our country, if the women generally should follow Mrs. Child’s bad example, and neglect their domestic duties to attend to the affairs of the state.” Other rebukes were more personal. Some friends publicly denounced her; others quietly avoided her. One Bostonian threw the book out the window with a pair of tongs.

Child’s readers shunned not just the Appeal but her other writings as well. Southern bookstores sent her publications back. She went from being “almost at the head of journalism,” as the Springfield Republican put it, to being “assailed opprobriously and treated derisively.” One of the writers she had recruited to write for The Juvenile Miscellany furiously criticized the Appeal’s author as “wasting her soul’s wealth” in radicalism and “doing incalculable injury to humanity.” Parents canceled their subscriptions to the Miscellany in droves. There had already been some trouble here: in the previous year, Child had published stories with antislavery themes that may well have displeased some parents. “Writers are respectfully requested to send no more contributions for the Miscellany, as it is about to be discontinued, for want of sufficient patronage,” read a notice in spring 1834. “After conducting the Miscellany for eight years, I am now compelled to bid a reluctant and most affectionate farewell to my little readers,” read a notice in the next issue. “I part from you with less pain,” Child bravely wrote, “because I hope that God will enable me to be a medium of use to you, in some other form than the Miscellany.”

The parents had spoken: an author who exposed the truth about America’s atrocities against Native Americans and its barbaric enslavement of Africans was not to be trusted with their children. Better to have young Americans believe that the country was good and its leaders benevolent than for them to confront the wrenching hypocrisy at America’s core.

Child resigned herself to a life of activism, ostracism, and poverty. Sometimes she claimed not to mind this; sometimes it hurt her very much. A decade later, as the abolitionist movement ebbed, weakened by enemies without and schisms within, she returned to writing children’s fiction and channeled enough childhood memories to write “Over the River and Through the Wood.” The irony that she is now known not for her incisive critiques of American racism but for one of the era’s most saccharine poems would not have been lost on her.

Often, as emancipation seemed a distant dream, she concluded that her life had been a failure. But sometimes there was evidence to the contrary. “I well remember,” a middle-aged woman who had been an early reader of The Juvenile Miscellany wrote to Child, “the zeal with which it was circulated, by a little group of schoolgirl abolitionists, of which I had the honor to be one. … Your influence over me,” the writer continued, “has always been ennobling, & purifying, & elevating, & stimulating to benevolence & charity.” How many other children had grown into more honest Americans because of this beloved children’s-author-turned-radical?

Child’s efforts to educate children had, indeed, had an effect. It was often immeasurable, but it was real. Today, as we struggle with so many of these same issues—how to reckon with our racial past in the curricula of our schools, how to fight against the historical distortions that continue to undermine the virtues necessary for democracy—the long reach of what we teach our children should motivate us to teach them well.

Adapted with permission from Lydia Maria Child: A Radical American Life by Lydia Moland, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2022 by Lydia Moland. All rights reserved.