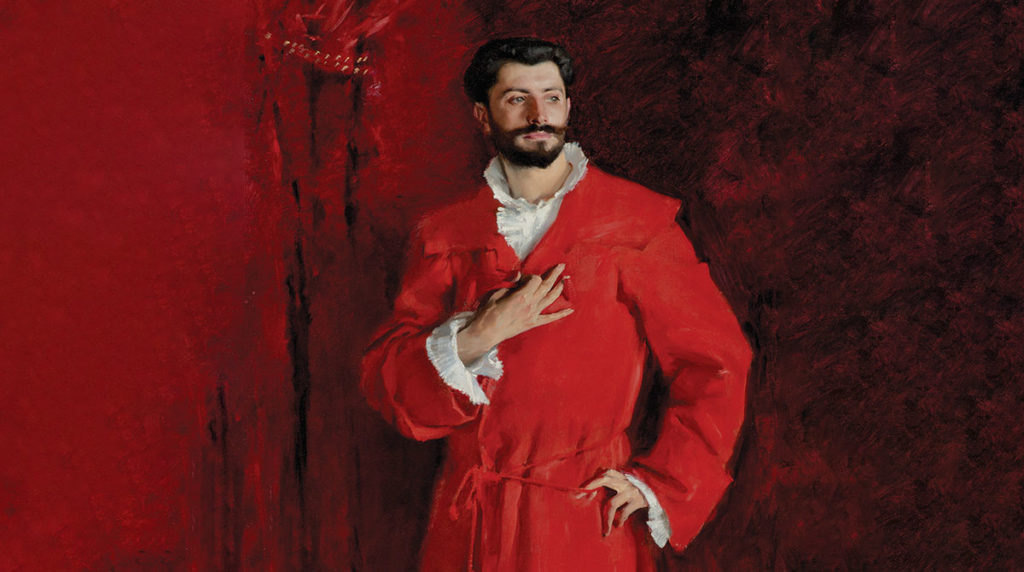

The Man in the Red Coat by Julian Barnes; Knopf, 288 pp., $26.95

The man in the red coat on the cover of Julian Barnes’s eponymous biography has neither a name nor a face—a fitting mystery, as Barnes had never heard of him until he happened on his “tremendous” portrait done by John Singer Sargent in 1881. A few pages in, the reader is told that the man clad in this sumptuous red coat was Samuel Pozzi and learns quickly that he was known as a remarkable gynecologist and an indefatigable lover. Sarah Bernhardt, who knew him in both guises, nicknamed him Docteur Dieu (Doctor God).

To be sure, Barnes does not take himself for a biographer god. “We cannot know,” he repeats over and over again. In his view, “biography is a collection of holes tied together with string and nowhere more so than with the sexual and amatory life.” He even admits that his story could begin in many different ways:

In June 1885, three Frenchmen arrived in London. One was a Prince, one was a Count, and the third was a commoner with an Italian surname … Or we could begin with a bullet, and the gun which fired it … [Or even] across the Atlantic, in Kentucky, back in 1809, when Ephraim McDowell … operated on Jane Crawford to remove an ovarian cyst containing fifteen liters of liquid.

He settled on the trip to England for the three gentlemen—Dr. Pozzi, Count Robert de Montesquiou, and Prince Edmond de Polignac—saving the other themes for later. At the end of the book, a whole cast will have emerged à la Proust “as in the game wherein the Japanese amuse themselves by filling a porcelain bowl with water and steeping in it little pieces of paper which … the moment they become wet, stretch and twist and take on color and distinctive shape, become flowers or houses or people, solid and recognizable.” The three men were emblematic of French society during the Belle Époque, which Barnes terms as “that time of peace between the catastrophic French defeat of 1870–71 and the catastrophic French victory of 1914–1918.”

Of the trio, Polignac was the “most invisible and unregistered. [He] was gentle, whimsical and rather hopeless.” He was also inept when it came to money: by the time he was 57 in 1892, all that he had left was his title. Montesquiou devised a solution that could have been dreamed up by Henry James or Edith Wharton. An American heiress, Winnaretta Singer, was on the market. The fact that Polignac was a discreet but known homosexual turned out to be his “unique selling point,” as Winnaretta was herself a discreet but declared lesbian. Their marriage was to be a resounding success.

Montesquiou was much more flamboyant. He fit the era’s stereotype of the ultimate homosexual dandy—vain, nasty, and elegant. We cannot know, as Barnes stresses, whether he indulged his urges. Whatever the case, the gossip endured. Montesquiou proved irresistible to many writers, and Barnes zigzags skillfully between fiction and fact. Was he the inspiration for Joris-Karl Huysmans’s character, the aesthete Jean Des Esseintes? Did Proust preserve him in the form of Baron de Charlus? Although Montesquiou joked, after the publication of Proust’s Sodom and Gomorrah, that he might now be known as Montesproust, he astutely pointed out to Proust that Charlus was more than anything else the heir of Balzac’s Vautrin. He may have felt that his own authenticity was threatened by all these literary shadows and envied Pozzi’s steadiness and invaluable work.

Pozzi was born to a Protestant family of Italian origin. He was thus something of an outsider in French society. But in those years of French acute nationalism, Pozzi was an exception. He was patriotic but convinced that “chauvinism is one of the forms of ignorance.” He learned from the pioneering surgeon Joseph Lister in Scotland, and from a visit to the Mayo Clinic, which had been founded by Englishman William Worrall Mayo in 1889 in Rochester, Minnesota. Pozzi’s bedside manner was so charming that his patients became his friends (in the case of ladies, sometimes more than friends). Montesquiou wrote with uncharacteristic simplicity that he had “never met a man as seductive as Pozzi … never saw him being anything other than his smiling, affable, incomparable self.” Everyone loved him, except perhaps his wife.

For all his worldly success, though, Pozzi was never able to escape the brutality of the period. And Barnes makes no effort to hide it. Readers should not be fooled by Barnes’s unconventional humor—Henry James’s praise, he writes, often seems “enshrouded, as it were, in what one might call bubblewrap”—or his comical and ironical take on a glittering, frothy society. Underneath it all lay the deadly violence of a nation obsessed by duels, ready to absolve murder, tolerating death threats. The 19th century was a time of amazing medical progress, yet a number of doctors were shot by irascible patients. Nothing was easier in the Paris of the day than to buy a revolver. But by the time the government decided to impose gun control measures, the First World War had erupted and “mass, rather than individual slaughter was of greater concern; and there was no problem with open carry in the trenches.”

In 1915, Pozzi inexplicably agreed to operate on the varicose veins in the scrotum of a tax collector named Maurice Machu. Why? We cannot know, but Barnes nevertheless speculates: “Perhaps the notion that, in the middle of mass European carnage, a man might worry about his scrotum appealed to his sense of the absurd. Or perhaps it was simpler: here, at least, is something I can fix.” The operation was a success, but three years later, the patient was still impotent. On June 13, 1918, Pozzi returned home from the military hospital where he operated to find Machu waiting for him. After entering Pozzi’s consulting room, Machu shot the doctor three times and then killed himself. Pozzi died a few hours later.

Julian Barnes wrote this book during the somber year that led to Britain’s vote for Brexit. In an afterword, he reveals that it was the figure of Samuel Pozzi, rational, enthusiastic, generous, “a sane man in a demented age,” who saved him from utter pessimism. It may be the best reason for us to read it now.