Warhol by Blake Gopnik; Ecco, 976 pp., $45

One should approach this elephantine account of Andy Warhol’s life—perhaps modeled on one of his endless films, like Sleep (1963)—with caution. To begin with, there are no source notes—some 7,000 of them are available online but not on a page. For a work that plainly hopes to be termed “definitive,” this is a curious omission.

Then there is the staggering length, almost 1,000 pages, made all the more challenging by Blake Gopnik’s verbosity, which reveals a steely determination to tell you far more than you ever asked to know. Given the two schools of biography—telling a rollicking good story and details be damned versus a minute chronology and reader be damned—this author opts for the latter. Apart from the book’s tantalizing start, which is centered on the moment when radical feminist Valerie Solanas, gun at the ready, almost killed Warhol in June 1968, the narrative takes the predictable path.

So we have the familiar story of Andy, the son of poor immigrants, a slight, sensitive, pimply-faced misfit, and the book’s impetus slows to a halt. The author’s professional interest—he is an art critic—takes charge, and the narrative explores the meandering stages by which an unpromising child discovers his talent, which naturally interests Gopnik but not necessarily the general reader. There are numerous small exhibitions to be endured, confident predictions of greatness to come, and much description of temporary quarters, with or without cockroaches, before something interesting happens. When, oh when, will Warhol reach “the cutting edge”? A refrain Gopnik repeats at least six times in the book’s first 300 pages.

The pace picks up once he begins to describe an unsuspected resolve behind a seemingly aimless series of experiments on Warhol’s part, and the single-mindedness of the ambition and will to fame that it concealed. The hesitancy, the self-effacement, the self-hatred (he had plastic surgery to correct the supposed defects of his nose) all vanished where his creativity began. He had no reason to be so sure of himself, but he was, and almost at once.

One of his instructors said, “Warhol wasn’t the best at taking a problem and solving it,” but “[i]f he had been running a tailor shop and [you] went in for a pair of pants, you’d come out with a lovely coat.”

In 1948, Warhol discovered French director Jean Cocteau’s haunting cinematic retelling of Beauty and the Beast and became a fervent admirer. No doubt he knew one of Cocteau’s famous maxims, Ne t’attardes-pas avec l’avant garde (“Don’t lag behind the avant-garde”).

Warhol’s awareness of this vital necessity began in 1947, when he was enrolled as a student in Carnegie Tech. He took a course in avant-garde advertising techniques and began to experiment with the blotting and scumbling innovations that he would incorporate into his later, and justly famous, silkscreen prints.

By then, he had had practical experience in the art of marrying fine art with advertising. While still a student, he helped build window displays for the upscale Joseph Horne Company in downtown Pittsburgh. Warhol had little drawing talent, but Milton Glaser, a noted graphic artist, thought he had something more valuable: “an enormous sense of style, and he could bring that burnished style to a product.”

When I was a member of the creative team at Lazarus in Columbus, once the biggest and most innovative department store in Ohio, lunch conversation every day was fixated on “What’s next?” to the point of obsession. As the immediate proof of the store’s up-to-the-minute approach, the shop windows were something of a barometer as they tracked the fickle tastes of their customers.

In retrospect we can see how Warhol’s singular personality, his special gifts, his secret need to shock people, and most of all his perseverance were valuable assets once he, with his messy hair and eccentric appearance, caught the eye of magazine editors. From direct marketing to editorial content is a short step. The content may be the same; only the goal is less obvious.

Warhol made surprisingly rapid progress from merchandising to advertising to art gallery walls. By the time he was 25, he had arrived at the ultimate nose-thumbing—a Campbell’s soup can, tenderly depicted and ready to be hung in a museum. What was going on here? Was it all tongue-in-cheek? Gopnik is sure it was. It was Warhol’s way of lampooning “the old-fashioned mediocrity of postwar marketing, even once modern design was supposed to have taken hold,” he writes.

Warhol and his like-minded lampooners—sculptor Claes Oldenburg and painter Jasper Johns among them—certainly stirred up a storm. One forgets how bold, impudent, and even sinister a reaction such glorification of kitsch—soon dubbed Pop Art—had caused. What scandalized some enraptured others. A critic for The Washington Post wrote that “their thesis [of the Pop artists] is anti-thesis; their philosophy, anti-philosophy; their technique, anti-technique.” Others were ecstatic for more practical reasons.

Gopnik makes clear how short a distance actually exists between today’s grubby, scrawling graffiti on a subway train and the upscale gallery dealer for whom making money from art has to trump aesthetic considerations of style. In 1982, as I was visiting one of Leo Castelli’s New York art galleries in New York, I noticed some graffiti on the wall next to the front door:

Art’$

What

$ellS

The soup can, as we all know, opened tempting vistas of high prices for Warhol and his lucky art dealers. The Campbell’s soup can was soon followed by Coca-Cola bottles, Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, the widowed Jacqueline Kennedy, and other high priests and priestesses of popular imagination, printed up in identical images like sheets of postage stamps. Even Warhol’s own image, eventually. He was famous, too.

True to form, Warhol opened up a salesroom of his own in Midtown Manhattan, called the Factory, one that also served as a studio and meeting place for a random coterie of friends and hangers-on. His theme was silver (speaking of money), and newcomers were treated to the sight of silver balloons floating lazily overhead and bumping against the high ceilings. It became an impromptu chrysalis for the idea of the moment, whether a new film, a new magazine, or more artwork. There was a resident rock band and a nightclub. At the height of Warhol’s almost mythical fame, his casual friends became famous themselves.

One of them was Edie Sedgwick, a rich girl with enormous eyes and a prepubescent figure. Edie’s traumatic childhood would lead to her death when she was only 28. But when she appeared at the Factory one day, something about her waiflike charm took hold of Warhol as it later did of George Plimpton, who edited a best-selling oral history about Sedgwick, compiled from hundreds of interviews with people who knew her. For Warhol, she was a twin being. They even began to adopt identical outfits. She would arrive with him on TV shows and provide his answers, tongue in cheek.

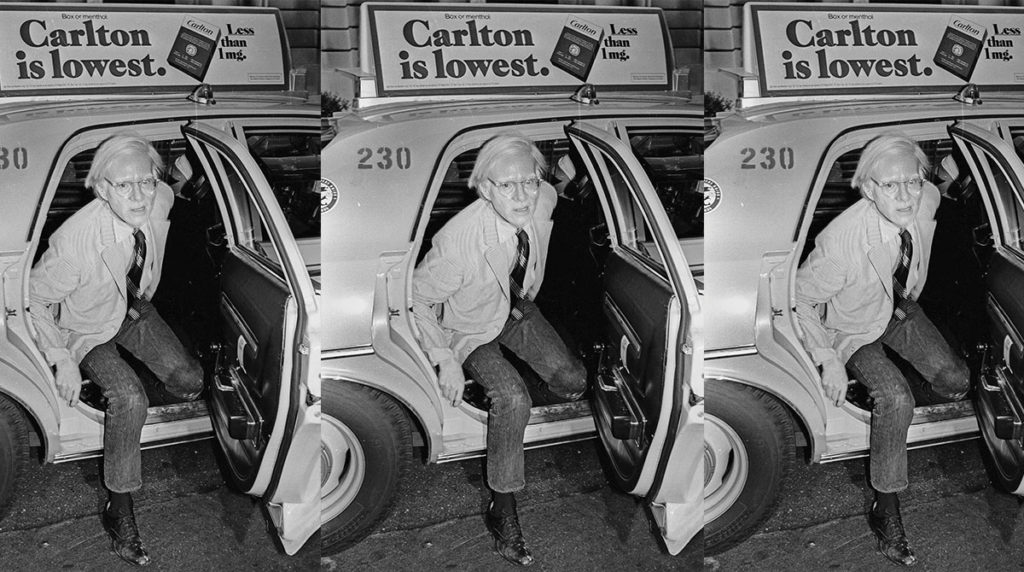

In June 1969, on assignment for The Washington Post, photographer Ken Feil and I went to the Factory to interview Warhol. I remember his unnerving silences and the feeling that he was transfixed at the angry center of a psychodrama that was constantly being written by others around him. It was not a very satisfactory interview, but one of the photographs Ken took, now lost, was quite otherwise. Ken positioned Warhol on a chair in front of a set of three-way mirrors, the kind used in department stores to show off views of the front and sides of an outfit. Then Ken angled his shot so that the image was cut and broken up into tiny slits multiplying into the distance, a Warhol infinitely reflected. How poignant. How appropriate. It should have been his epitaph.