In the Matter of the Commas

For the true literary stylist, this seemingly humble punctuation mark is a matter of precision, logic, individuality, and music

1.

At the Art Institute of Chicago, Joan Didion and her daughter, Quintana, were looking at a painting by Georgia O’Keeffe. The work, Sky Above Clouds IV, hung across a landing, so they had a gulf of air between themselves and the flat white shapes that span a long wall at the museum. It is a giant painting, practically a mural, as wide as the abstract Barnett Newman canvases that you can walk along and let fill the whole of your vision. But this work floats at a distance, celestially, and you just look out at it. There are 192 square feet of clouds. You are in an airplane. “Who drew it?” Quintana whispered to her mother. “I need to talk to her.” On which Didion reflected, in her 1979 essay collection The White Album:

My daughter was making, that day in Chicago, an entirely unconscious but quite basic assumption about people and the work they do. She was assuming … that the painting was the painter as the poem is the poet, that every choice one made alone—every word chosen or rejected, every brush stroke laid or not laid down—betrayed one’s character. Style is character.

Didion held on to that belief throughout her career. How you write or paint is who you are, she thought. Sometimes she went further. Style not only showed your character but, as she wrote in a late novel, might even reveal your politics, your ideas about the world—what you had come to think and believe.

In his review of The White Album for The London Review of Books, Martin Amis mocked the scene with Quintana at the Art Institute. Style had nothing to do with character, he wrote. It was a ridiculous notion. In Chicago, Didion showed “how quickly sentimentality proceeds to nonsense,” Amis wrote. “If style were character, everyone would write as self-revealingly as Miss Didion. Not everyone does.” Plenty of writers remain anonymous, or produce books that seemingly have little to do with their real lives. Didion had fallen in love with an idea that could not withstand scrutiny, according to Amis. “The extent to which style isn’t character,” he wrote, “can be gauged by (for example) reading a literary biography, or by trying to imagine a genuinely fruitful discussion between Georgia O’Keeffe and Miss Didion’s seven-year-old daughter.”

2.

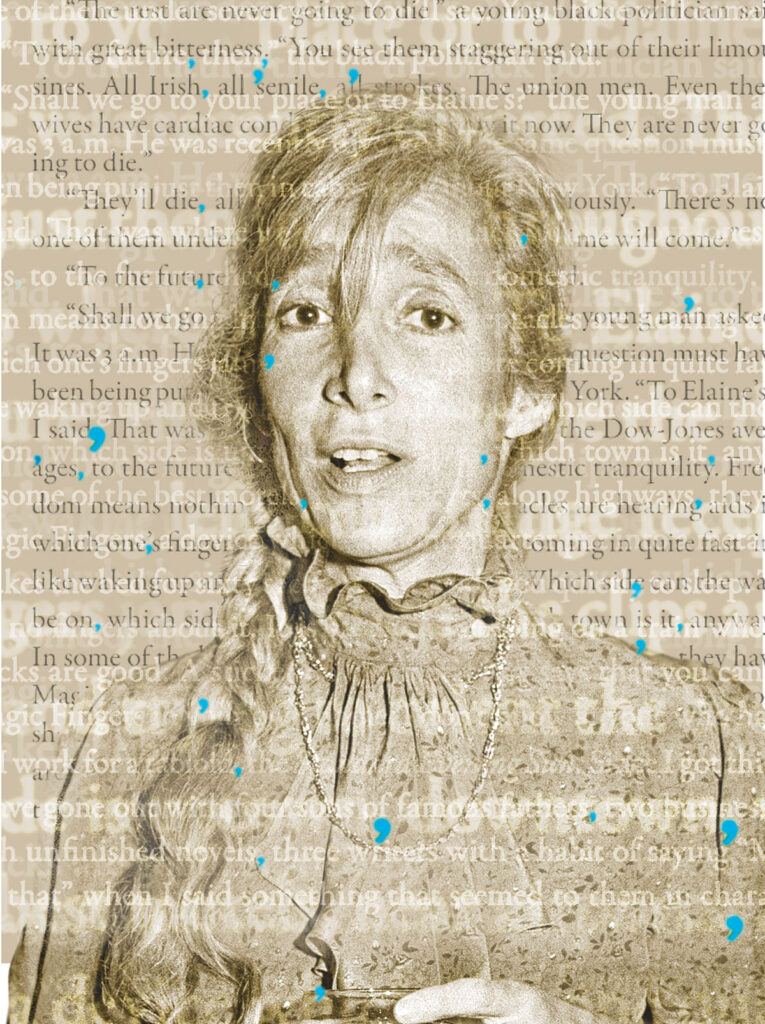

The most conspicuous mark of Renata Adler’s style is its abundance of commas. In her two novels, Speedboat (1976) and Pitch Dark (1983), there are a few sentences that edge on the absurd: “For some time, Leander had spoken, on the phone, of a woman, a painter, whom he had met, one afternoon, outside the gym, and whom he was trying to introduce, along with Simon, into his apartment and his life.” A critic tallied it up, counting “40 words and ten commas—Guinness Book of World Records?” Each of those commas had its grammatical defense, but Adler’s style did not comply with the usual standards of fluent prose. She cordoned off phrases, such as “on the phone,” that other writers would just run through. One reader, responding to a 1983 New York magazine profile of Adler, wrote in a letter to the editor, “If the examples of Renata Adler’s writing … are typical, Miss Adler will never make it to the road. The way is ‘jarringly, piece by piece, line by line, and without interruption’ blocked by commas.” The reader was quoting one of Adler’s own comma-laden critical phrases against her. The editors titled the letter “Comma Wealth.”

Adler’s comma usage differs from the balanced rhythms of 18th-century essayists, as well as from the breathless lines common among American writers after Hemingway. Her punctuation jars, and turns abruptly, like a skater’s blade stopping and sending up shards of ice. She likes to leave out conjunctions in chains of adjectives, as in her film review of “a leering, uncertain, embarrassing, protracted little comedy.” Certain lines of hers work almost entirely by carefully placed commas, which tighten the style, each one a rivet on the page: “But this I know, or think I know, that idle people are often bored and bored people, unless they sleep a lot, are cruel.” A hesitation, a stutter, and then a swing into the qualification (“unless they sleep a lot”). Interestingly, no comma in “bored and bored people”: grammar sacrificed for rhythm and speed.

Not everyone saw the elegant precision in how she pointed her sentences. After one of her books came out, a critic wrote that “virtually every sentence is peppered with enough commas to make the prose read like a series of hiccups.” Another letter writer complained of her “muddled syntax and wandering, endless sentences.”

But Adler’s style had its admirers, too. “Nobody in this country writes better prose than Renata Adler’s,” a critic wrote in a Harper’s review of her first novel. New Yorker staff writer Elif Batuman recently said that she could not think of a living stylist she admired more. But the most insightful comment might have come from a man splitting the difference. At The New York Times, where in 1968 Adler had become the daily film critic, editor Abe Rosenthal addressed a concerned colleague by first conceding that Adler was no great stylist, and then suggesting a metaphor: She’s olives. The readers will grow to like her.

3.

Writers quoting the phrase style is character like to attribute it to Didion. But in her essay on O’Keeffe, Didion italicized the line to indicate that the words were not her own. The substance of the idea goes back at least as far as the Comte de Buffon, a French naturalist and mathematician, who, in his 1753 “Discourse on Style,” wrote, le style est l’homme même, or “style is the man himself.” According to Buffon, the facts of a book are external, belonging to the world. The arrangement and phrasing, however, belong to the writer. Buffon saw a neat division between form and content: the world provided the content, and the writer provided the form. He did not mean to suggest, by his redolent phrase, that style was equivalent to character—only that style is the human side of a written work.

Some early editions of Buffon’s discourse included a slightly different articulation: “le style est de l’homme même,” or “style is from the man,” which more clearly expresses Buffon’s meaning. But the line in its better-known formulation—“style is the man himself”—prevailed, both in French and in translation. By the 19th century, the saying was well known in the world of English letters, merging in spirit with the phrase “style is character.” Writers continued to quote one line or the other well into the 20th century. Didion’s writing teacher at Berkeley alluded to Buffon in a critical essay on Hemingway. Norman Mailer, perhaps Didion’s favorite contemporary writer, imbued “style is character” with a moral edge. “A good style cannot come from a bad, undisciplined character,” he said.

Style came to be understood as the personal expression of an artist. This marked another departure from Buffon’s thought. In saying that style was the “man himself,” Buffon did not mean that every writer should bring his style to an individual pitch of self-expression. “Style is simply the order and movement one gives to one’s thoughts,” he wrote, in an accepted definition of the time. But not all kinds of movement were good. The order should be a “continuous chain.” He dismissed writers “who at separate times write in detached fragments,” since they “cannot unite these save by forced transitions.” Style, as a universal matter, meant clarity, concision, rigor, and fluency.

The interpretation that came down to Didion—style as one’s personal mark—was forged largely in the 19th century. In 1888, Walter Pater invoked Buffon’s phrase to exalt style as an artist’s “individuality, his plenary sense of what he really has to say, his sense of the world.” Unlike Buffon, Pater was ecumenical: “Style in all its varieties, reserved or opulent, terse, abundant, musical, stimulant, academic, so long as each is really characteristic or expressive, finds thus its justification.”

4.

Adler sang of punctuation. In Pitch Dark, there is an associative run, typical of her novels, that reads: “And this matter of the commas. And this matter of the paragraphs. The true comma. The pause comma. The afterthought comma. The hesitation comma. The rhythm comma. The blues.” I wonder if everyone hears the music in that “riff,” as she calls it, with the rhythm of the short fragments and the satisfaction of the last monosyllable. There is also, within the musical list, a legitimate sorting of functions. The afterthought comma, Adler said, was when you wanted to add something, and there was no obvious way to do it. The true comma was the grammatical one, separating phrases or clauses. When spoken, it could function differently from other commas. To read out loud, “For some time, Leander had spoken, on the phone, of a woman …” you should not rest at each phrase. The true comma does not always require a pause.

Punctuation controls two things: logical separation and breath. In Adler’s words, “part of it is meaning, and part of it is cadence.” Writers weigh each role differently. Didion wrote that grammar was a piano she learned to play by ear, and she seems to have given priority to breath. Adler learned grammar in school, where she diagrammed sentences, and then at The New Yorker, which gave far more weight to logic. The magazine, where she began working at age 24, was alternately beloved and deplored for its commas. If a phrase was not essential to the sentence, the editors wanted it enveloped: thus “on the phone,” a wrapped-up appositive. (“May I offer you a comma?” the magazine’s editor, William Shawn, used to say to Adler in editing sessions.) Punctuation grew into a dogmatic inheritance, a passion, and a trademark of the magazine. E. B. White wrote that “commas in The New Yorker fall with the precision of knives in a circus act, outlining the victim.”

Knives are an apt metaphor. The first systematic survey of English punctuation, published in 1785, recorded that the Greek komma means “a segment, or a part cut off [from] a complete sentence.” The word comes from koptein, to cut. Precision, too, is a kind of cutting, a drawing of lines. It has a coincident etymology in Latin: praecidere means “to cut off.” Adding commas does not necessarily make your work precise, and you can write clearly without much punctuation. Precision might come, for example, in short declarative sentences. It relies on other things, too, such as diction, the mot juste. But the wish to separate accurately, to put different things into different cells, connects, at least in Adler’s case, to an actual grammatical usage. When she launches into one of her riffs, when she begins listing, or when she describes a phone call, her work suggests the old definition of thought as collecting and dividing: cutting between concepts as a good butcher slides his knife along the natural joints.

5.

In an American rhetoric manual published in 1883, minister Austin Phelps listed a set of clichés about style, with the purpose of refuting each one in turn. The last cliché reads,

“Style is character.” Buffon has it, “Style is the man himself.” But body and soul are that: are they style? This, again, is descriptive, not definitive. Sometimes it is not true. The chief thing which does not appear in some specimens of style is the person of the writer.

Like Martin Amis a century later, Phelps contended that if style were character, then anonymous authorship would be practically impossible. He doubted that there was any telling relationship between a book and its writer. Even when the author signs his name, Phelps wrote, “are we not obliged to confess, in reading a book, that we cannot become acquainted with the man who wrote it? He remains at the end as much a stranger as the reader is to him.”

I believed I knew Adler from the words she chose. Having read her two novels, her essay collections, her book on libel law, and her reporting, I could not say that we were still strangers. (Even more curious: I was certain that she, in a sense, knew me.) Henry James spoke of finding an author between the lines, and I thought I had done as much with Adler. She seemed to be present even in her simplest prose—in emails, for example. I had been preparing an academic study of her career as a journalist and was interviewing her by phone. When we were finally able to meet each other, in 2022, she emailed me directions to her house in Connecticut. The address would not be easy to find, she warned. Driving through the woods, I was to look for the house with a “weathered cedar stockade fence.”

I had never used the word stockade in my life. I was not completely sure how to distinguish cedar, at a distance, from any other wood. Approaching Adler’s house, I saw what I would describe as a fence, maybe an old fence. As it turned out, the fence had a whole story—it had led to a legal battle with her neighbor—but I do not need to go that far in the direction of biography. The phrase alone, “cedar stockade fence,” casts doubt on whether there can be such a thing as anonymous authorship, as Phelps believed. Even the plainest lines betray us: The cat is on the mat. Who might write the gray cat, or the tabby cat? Who would use the word kitty to avoid the internal rhyme? Who would shun the copulative verb “to be” in favor of sit or stand or prowl? Even the “neutral” cat is on the mat is a choice the author made. It reflects who he is, perhaps what he does, certainly what he sees or knows. At the very least, one self-evident claim holds true: style betrays how you would speak, in a certain situation, given a certain role.

But Phelps’s objections cannot be defeated just by disproving the idea of anonymous authorship. He had another, subtler point about the error of seeing style as character. Followers of Buffon, he wrote, offered an incomplete definition. Character is just one part of style. In his lectures, Phelps enumerated seven virtues in writing: purity, precision, individuality, perspicuity, energy, elegance, and naturalness. A confusion had arisen, he implied, because people mistook individuality for the whole of style. Individuality is what “Buffon had in mind,” he wrote, and “which others have meant by saying ‘style is character.’ ” Individuality is the only virtue to which Phelps dedicates no further space in his lectures. Its pursuit would be fruitless. “The more sedulously a speaker studies and strives to gain it,” Phelps wrote, “the less he will have of it.” Individuality would come, if it came at all, “unbidden.”

Many of us write without individuality. Our style is generic enough that nobody could identify us from our prose. But that does not mean that our prose is disconnected from who we are. Our plain sentences are still signed by us. They reflect that we have not developed any special perception. Pierre de Marivaux, a contemporary of Buffon, and in some ways a dissenter from Buffon’s more classical views on rhetoric, set a challenge: “Find me one author who has deeply studied the human heart and does not have a rather singular style.” I suppose that is what I saw, reasonably or not, in Adler’s commas, and in the weathered cedar stockade fence.

6.

In a book talk, Adler said about a particular line in Speedboat:

I looked back for a sentence that went something like, ‘At the age of 26, Kate, though not promiscuous, had slept with most of the decent men in public life.’ … On the one hand, if you’re reading very fast, you can’t just read over that sentence and say, ‘Ah, yes, so she slept with—,’ and go on to the next sentence. You have to pause for a minute. But if you pause too long, if you stop them too long, then it’s just a smart-ass thing to say, which I didn’t want either. So there’s this business of tuning sentences, which is such an intriguing part of writing. … I don’t have plots. I don’t have other stuff. So all I can do is that tinkering.

Back in the 1960s, as a doctoral student in comparative literature at Harvard, Adler published an essay on Rainer Maria Rilke, in which she described his 1910 novel, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, as an “almost purely stylistic achievement.” Like music, she wrote, the book could not be translated. Rilke toyed with language, and “in opaque tinkering lies the artistic merit of the journal.”

This business of tuning sentences. This tinkering. I have the image of a woman working on a car in her garage, or a composer seated at his piano, making small adjustments to a score. Adler spent a great deal of time rearranging the fragments she had written, putting things in, cutting things out. At The New Yorker, Shawn once moved around the parts of a story she had drafted. “Maybe everything does go anywhere,” she thought, reading his version. But she did not really believe it.

In Writing Degree Zero, Roland Barthes described the “loneliness of style.” It is “the writer’s ‘thing,’ ” he wrote, “his glory and his prison, it is his solitude.” Adler is meticulous about her style. During her time as a film critic, she lost days to dealing with New York Times editors, who kept changing her prose, making edits that she had already thought of and decided against (“there was rarely the conception that in doing sentences a writer chooses among options,” she wrote about the experience). Her pieces for the Times sometimes appeared without her having seen the final version. She was happier at The New Yorker, where, though they might propose significant changes, the magazine’s editors made sure “not to attribute to the writer a single word, or a single cut, or a single mark of punctuation, which the writer had not seen and, in some sense, approved.” She has always cared about those things. For without the grand plot of a detective novel, without the large, vivid characters of Austen or Dickens, what Adler has is style. It is her solitude, her glory, her thing.

7.

The biographical fallacy lures us with its easy connections, even in the matter of the commas. A famous classicist wrote, for example, that “the random quizzical ethos of Laurence Sterne, and even his rather frail health, are reflected in his punctuation.” Ignoring the question of what a “quizzical ethos” might be, the idea remains specious. The opposite could as well hold true: a random, frantic style might come from an abundance of energy rather than frailness.

Still, I am tempted by the apparent connections to Adler’s life. Consider the hesitation comma: Could you hear in that, not just in her use of it, but in her naming of it, something of Adler’s self-described shyness? She inserted, in so many sentences, a small “I think” or “I believe,” as if she did not want to offend someone by making too strident a claim. The afterthought comma: Adler’s obsessiveness, the way she frets over an incident for days, and her sense that the words come only later, after they are needed. “I’m a person who can never think what I want to say until it’s too late,” she said in an interview with the Kunhardt Film Foundation, when asked to define herself. “That’s about it. It might occur to me when I get home. That’s it.” Or maybe the afterthought comma reflected her tentativeness, the way she qualifies her speech, offering a sentence or a word and then rescinding it, doubting it, a few seconds later. As in, “It made such a mystique, a word I just realized I don’t care for at all, attach to the question of whether one was published in The New Yorker.” You could hear, in the self-revision, a wish to say something beautiful and true, under the timed pressure of conversation.

But all this speculation is gainsaid by her essays, which show little hesitation at all. “Unless you’re going to be fairly definite,” she said once about nonfiction, “what’s the point of writing?” That alone suggests a different character. It introduces a counterpoint to her shyness.

There is another species of biographical connection that does not require a one-to-one mapping of literary features to specific personal traits. It is a different kind of knowing, of a more intimate, less definable sort. It involves attending to style, but not trying to conclude too much. To merely think: she is the type of person who says things in this way. She is a person for whom words come out like this. This is how she holds her pen, her stylus: such an angle against the page, such pressure on the ballpoint. And to go no further than that.

Look, for instance, at a famous line from Speedboat: “I think sanity, however, is the most profound moral option of our time.” Many people would edit that sentence. Cut “I think.” Cut “however.” Leave out the hesitation, the pause. When Adler’s friend Daniel Patrick Moynihan quoted the line in a campaign speech, he flattened it just like that: “Sanity is the most profound moral option of our time.” It says something about Moynihan, and perhaps about political speech, that he quoted Adler in this way. He practiced a version of what Montaigne described: giving a phrase “a particular twist with my hand, so as to make it less purely another man’s property.” Montaigne, who culled lines from hundreds of sources, wanted to leave an imprint on what he borrowed. Moynihan left his mark, too.

“A phrase is born into the world both good and bad at the same time,” Isaac Babel wrote. “The secret lies in a slight, an almost invisible twist.”

“A writer’s biography,” Joseph Brodsky wrote, “is in his twists of language.”

8.

Interviewer at Vice: “I was always drawn in your books, in your novels, to all the run-ons and commas. That style has always made sense to me, but some people can’t stand it … What do you think the purpose of writing in this way is? What purpose does it serve for you?”

Adler: “Are you a great fan of Evelyn Waugh?”

The interviewer had not read any Waugh, but no matter. Adler could recount the scene she wanted to discuss and even knew a few lines by heart. (“It’s almost the only thing I care about,” she said to me. “Lines are what I listen for and what come to life for me. Even overheard, not interesting lines.”) In the interview, she described a climactic moment in Waugh’s 1934 novel, A Handful of Dust. A woman is having an affair, and she finds out that her son has been killed. Her lover and her son happen to share a name. When the woman gets a phone call about the death, she thinks her lover has died. But the information does not add up, and in the middle of the sentence, she realizes it is not her lover but her son: “She frowned, not at once taking in what he was saying. ‘John … John Andrew … I … Oh thank God …’ Then she burst into tears.” Adler repeated that line to me, almost verbatim, down to the final words: “Then she burst into tears.” A whole drama unfolded in Waugh’s ellipses. “The guy was so funny and sharp to be able to do that in the middle of the sentence,” she said in the Vice interview. “It’s a very different use of language. For example, take Hemingway. Hemingway is also very controlled, but he isn’t drilled for precision. Hemingway has just been careful not to go off the rails.”

There are Waugh writers and Hemingway writers, in Adler’s taxonomy. She and Didion, often placed together as striking, intellectual, neurotic American women who wrote novels in the 1970s, fall on different sides of the line. “It was my least favorite part of Joan’s writing—the Hemingway part,” Adler told me. “Very different from a Waugh kind of writer.” Both women liked both men’s writing, but they proceeded, in a sense, from one or the other. Adler, who admired Didion, still resisted what she called “the Hemingway and.” (“It was a hot day and the sky was very bright and blue and the road was white and dusty.”) Didion used that and a lot. Adler preferred sharp turns, abrupt stops, a different rhythm entirely.

The author of a 1984 essay in Commentary that compared Didion and Adler with something less than intellectual rigor (“I think of them as the Sunshine Girls, largely because in their work the sun is never shining”) contended that readers could not tell their sentences apart. The writer listed a few examples, which, he claimed, could be exchanged between novels “without, I suspect, anyone noticing.” On the phone, I read these sentences out to Adler. “I am less and less convinced that the word ‘unstable’ has any useful meaning,” was one. “That must be Joan,” Adler said. “I can’t imagine using the word ‘unstable.’ ” I read another: “What an odd notion it was that fiction was just a matter of getting facts completely, implausibly wrong.” That was hers. Adler knew from how the sentence landed on the last monosyllable. You could also tell, I thought, from the juxtaposed adverbs. Finally: “I guess I’m just neurotic.” “That’s me,” Adler said. “That’s me for sure, because that’s me quoting myself talking to David Selznick.”

Speaking with Adler about grammar, I paraphrased a line from Didion’s essay on Hemingway: some writers care about punctuation, and others don’t. Those who do, I added, are the better sort.

“Well, sometimes not,” Adler said.

Her answer surprised me. But sometime later, while reading Middlemarch, I found a quotation describing how Dr. Casaubon had semicolons in his blood.

9.

Martin Amis came around in the end. Having once mocked Didion, he took back his words in a late memoir. “Style, of course, is not something grappled on to regular prose,” he wrote. “It is intrinsic to perception. … And style is morality. Style judges.” It becomes hard to argue, once you have conceded that style is perception, morality, and judgment, that it is not also, in a sense, character. Amis had traveled through one of the most famous rebuttals in literary history: from Samuel Johnson, who held that language was the dress of thought, to Wordsworth, who said it was the incarnation.

At the start of Pitch Dark, Adler asks, “Do I need to stylize it, then, or can I tell it as it was?”

By the end of the novel, she will say to us, “But I believe, you know, I actually, naturally think, in long, sad, singing lines.”