I once interviewed a cancer survivor named Betty for an essay on life-threatening illnesses. As a courtesy I gave Betty my most recent book, inscribed to her. The next day she called me at home. “I don’t usually ask interviewers to do this,” she said, “but would you read my quotes back to me for accuracy?

“I don’t usually do that,” I responded. “Why do you ask?”

“You know that book you gave me?”

“Yes.”

“You inscribed it to ‘Barbara.’ ”

I read Betty her quotes.

How could I have done it? The only explanation I could come up with is that Bettys, to me, are short and round (Betty Boop, Betty Crocker, Betty Friedan). Barbaras are long and lithe (Barbara Stanwyck, Barbara Eden, Barbara Kingsolver). This Betty was tall and slim, a Barbara if I ever saw one. But that’s not the point, is it? The point is that my brain’s wiring routinely shorts out during the power surge of book signing. What should be an occasion of high honor becomes one of low apprehension. How will I goof it up this time?

Signing books is not for the faint of heart. Opportunities for gaffes await any writer composing inscriptions. While signing copies of a novel she’d just published, the English author Monica Dickens inscribed one to “Emma Chisit.” That was the name murmured by a customer handing over her book in a Sydney, Australia, bookstore. Or so Dickens thought. It turned out that the prospective bookbuyer was asking, “How much is it?” in a thick Aussie accent.

One colleague after another has told me book-signing horror stories involving misspelled words, inane observations, and forgotten names. Fiction writer Robert Olen Butler said he feels the greatest signing pressure close to home, when inscribing books for people who think the Pulitzer Prize winner knows them better than he actually does. At times this results in what Butler calls “nominal aphasia,” occasions when he can’t even remember such a book buyer’s name. Butler’s not alone. During a book signing in California, poet and NPR commentator Andrei Codrescu looked up to see the woman who had been his first American girlfriend after he’d migrated from Romania three decades earlier. Codrescu remembered the woman’s face, and much about her, just not her name. She sensed his quandary, and refused to tell him. On another occasion Codrescu was called up short when an escort who’d spent the day driving him around Denver asked him to sign a book for her. He blanked on her name too. Finally Codrescu remembered and signed it to “Lisa.” He remembered wrong.

[adblock-left-01]

Presumably this was the same escort who returned a book to Denver’s Tattered Cover Book Store because a client had signed it for her with the wrong name. After giving this woman a fresh copy, the store’s events coordinator added the botched version to a stack of other mis-signed books in her office (including one by an author who had forgotten to write his own name).

The assumption that anyone who can write a book can sign a book is based on frail logic. Although both involve recording words on paper, signing bears only a superficial resemblance to actual writing. If book writing is like giving a well-prepared lecture, book signing more closely resembles improv. Unlike manuscript preparation, in which authors can deliberately compose their thoughts for readers who remain far away in time and space, signing published books requires them to write quickly, spontaneously, and—at signings—while a book buyer stands by expectantly, eager to assess the results.

Authors routinely wilt under this pressure. Inscriber’s block is commonplace. On the many occasions when she couldn’t think of anything to write while signing copies of Bimbos of the Death Sun, Sharyn McCrumb took to scribbling, “See p. 33.” On page 33 of her novel McCrumb depicted a blocked writer who couldn’t think of anything to write.

You might think that falling back on stock inscriptions would solve that problem, but think again. The risk in relying on a canned message is that those in the know will take umbrage. When Christopher Dickey got engaged, his father—the poet and novelist James Dickey—inscribed a collection of his poetry “at the beginning” for him and his fiancée. Knowing that his father used this inscription routinely, even for perfect strangers, Christopher ripped the book apart and threw its pages into the street.

I seldom ask colleagues to sign books for me. Spare them the agony, I figure. Perhaps if I did, I’d be more sympathetic to the hopes and dreams of inscription seekers. After harrowing hours of signing my own books at a book fair, I asked the author of a book about haunted houses to inscribe one for my son Scott. First I had to stand in line, however. And, like those before and behind me—like book buyers who had been approaching me all day long—I was keen for a warm, personal message from the author to my son. Something to make him feel special, and make me feel important. She wrote, “To Scott. Happy hauntings,” followed by her name. I felt let down by this stock inscription.

The problem in book-signing transactions is that the aspiration gap is so vast. The hopes of readers are usually too high, those of authors too low. Book buyers want an elegant, unique, even witty inscription that will flatter them and impress their friends. Authors want to get through the ordeal with as few gaffes as possible, then go for a drink. It’s a hard gulf to bridge.

Mystery writer Lawrence Block has observed that writing a book is the easy part. Far more demanding is signing copies of that book once it’s published. As best-selling author Peggy Anderson (Nurse) once told me, “People want you to say something special and intimate, spur-of-the-moment, in the 30 seconds you have for each one in a long line of people. My position is that it’s harder to autograph the book than to write it.”

At a signing in my hometown, the friend of a woman I’d dated in high school asked me to sign a book for her. My onetime date had gone through a divorce, her friend said, had health problems, and was depressed. Perhaps a reassuring message from the author would cheer her up. I can’t remember what I wrote, but I’m sure my words weren’t up to the challenge. They seldom are.

Publishers should offer authors a workshop on book signing, one with sessions such as “What to Do When Your Mind Goes Blank,” “Preventing Booksigner’s Wrist,” and “Which Page Should You Sign?” As novelist Gay Courter discovered early in her career, there is far from a consensus answer to this last question. At a book and author event in Alabama, she sat beside New York Times columnist-turned-novelist Tom Wicker. After Courter had signed a few copies of her fledgling novel The Midwife, Wicker observed that she was autographing the wrong page. According to Wicker, a book’s title page was the right one to sign. When he was an aspiring author, Wicker told Courter, a prominent colleague told him that “real” writers sign there because it adds more to a book’s value. After that, Courter began signing the title page of her books. When others asked why, she explained, “Because that’s the right page.”

Is it? That’s a controversial question among authors. The real traditionalists don’t just sign the title page but cross off their printed name before writing their signature, as if replacing the printed version with a written one. (One author stopped doing this after a relative asked him to please stop defacing his books.) Others simply sign the first possible page. In a compromise approach, Robert Olen Butler sometimes writes an inscription in the biggest white space available, and then repeats his signature beneath the printed one on the title page. William Zinsser thought that signing a book’s title page was a Victorian affectation, however. Zinsser, whose 19 books included the classic On Writing Well, signed the first blank page, “right where people look first.”

Book signing began as a defense against piracy. A 1745 edition of Hoyle’s book of rules for card games advised that unless it featured signatures by both its author and publisher, the book wasn’t genuine. In time that practice gave way to having “presentation copies” (those given by the author) and “inscription copies” (those inscribed at the customer’s request), signed by the author alone. Only in the past couple of centuries have inscriptions become “personalized.” Some noted authors have been less likely than others to sign their books. Arthur Conan Doyle did sign, but seldom personalized an inscription. A. E. Housman, William Faulkner, and Thomas Hardy were reluctant to sign at all. When Virginia Woolf had tea with Hardy, his wife suggested that he inscribe a book for their guest. And so he did, a copy of his short story collection Life’s Little Ironies, in which Hardy misspelled his guest’s last name “Wolff.”

Some months later Virginia Woolf herself sent her friend Vita Sackville-West a copy of her new novel To the Lighthouse. Inscribed on the flyleaf was, “Vita from Virginia (in my opinion the best novel I have ever written).” Sackville-West thought this was uncharacteristically boastful. Then she riffled through Woolf’s book and discovered that it was a bound dummy with blank pages.

For scholars, books that are personally inscribed can be an invaluable aid when trying to discern an author’s sensibilities. Among the most famous inscriptions in literary history is T. S. Eliot’s mixed message to Ezra Pound in Pound’s copy of The Wasteland: “Il miglior fabbro.” (“The better craftsman,” a phrase he borrowed from Dante’s The Divine Comedy and in later editions turned into a dedication; Pound had extensively edited a sprawling draft of Eliot’s epic poem.)

Presumably, words written in its author’s hand would increase a book’s value. Except in works by the most celebrated writers, however, an author’s inscription doesn’t add value to a book unless it’s unusually clever or revealing or conveys the volume to someone else of note. In some cases, an author’s signature alone can make a book more valuable to collectors than a personalized inscription (perhaps because so many of those inscriptions are stock, inane, or annoying, raising questions about the ability of the author to write in the first place).

When it comes to writers of lesser renown—those euphemistically known as “midlist authors”—inscriptions and signatures not only don’t raise the value of their books, they may even reduce it. An autograph collector once told me about finding two copies of the same book in identical condition at a used bookstore. One was signed by its author, Nan Britton (Warren Harding’s mistress); the other was not. The unsigned copy cost three dollars more than the signed one. After purchasing both copies, the collector asked why the two books were priced differently. “Because someone scribbled in one,” responded the bookseller.

[adblock-right-01]

This lends credence to the speculation of author Laurence Leamer (The Price of Justice) that as signed books become ubiquitous, a day will come when a premium will be charged for books that aren’t signed. As it is, the craving for an author’s signature is so widespread that during an author’s event Leamer was once asked to sign a book he’d merely blurbed for someone else.

Early in his career, Philip Caputo was placed between Erma Bombeck and Dinah Shore at a signing in Nashville. A huge number of customers lined up at Bombeck’s table, and nearly as many stood before Shore’s, “like the line for the opening night of Gone With the Wind,” Caputo recalls. “Mine was like the line at a Bronx bus stop.” Finally a few customers dribbled up to his table, then several dozen. When he inquired about their interest, some told the novelist that they wanted a signed book but didn’t feel like waiting for Bombeck or Shore.

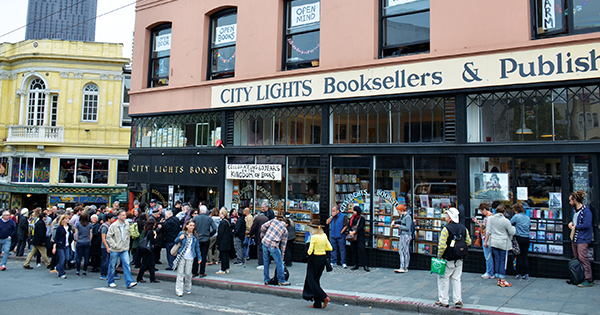

In a sense, the actual signing of books has become an almost incidental part of a signing, an excuse to assemble more than a reason. (In a time when nouns commonly become verbs, “signing” is a far less common example of a verb doubling as a noun. So is “reading,” as in, “I gave a reading.”) For those in the audience, readings and signings hold out the hope of literate company as well as personal contact with a demi-celebrity, if not a household name. As the most common setting for such events, bookstores have become the literary equivalent of churches for those seeking a bookish congregation. Human company is something that stores can offer but Amazon can’t. That’s why getting a book signed by its author can be more of an excuse than a reason for attending writer-reader events.

At one such gathering in Washington, D.C., an ebullient woman told me how much she loved my book, the one she’d picked up at a dollar store. Realizing her gaffe, she then tried to pivot by telling me what a great writer I was. When I asked which book of mine she was referring to, the woman mentioned a novel written by another author at the same gathering. I didn’t have the heart to tell her she was talking to the wrong author. When she later approached me with a copy of my colleague’s novel to sign, I had to break the bad news.

Being asked to sign a colleague’s book is among the many hazards of participation in what Margaret Atwood has called “the dreaded group signing.” At these fusions of flea market and literary joust, authors can relive their high school days by engaging in competitive book inscription. The probable winner of the Most Books Signed event is James Ellroy, who autographed the entire first printing of his memoir My Dark Places, all 65,000 copies. (The last few hundred signatures were barely legible.) Other categories in this competition include Best Writing Instrument, Most Books Signed Per Hour, and Fastest Signer. Perhaps because writing is not his primary occupation, Gen. Colin Powell saved time with military precision when signing his autobiography: six seconds per copy. Despite the handicap of his 14-character last name, Arnold Schwarzenegger was able to sign 400 copies an hour of his autobiography by reducing that name to one S, a line, and two g’s. Athlete-authors seem to excel at marathon signing events. On the same night that he spent three hours and 46 minutes playing in his 2,368th consecutive baseball game, Baltimore third baseman Cal Ripken Jr. wore out 16 felt-tip pens signing 2,000 copies of his autobiography, from midnight to 3 a.m. at a bookstore in Towson, Maryland.

Writing too many words in too many books puts a writer at risk for signing-related injuries, of course. This is a little-appreciated occupational hazard of being a contemporary writer, particularly one who’s successful. Elbow pain that resulted from signing books during a publicity tour of 20 cities forced Robert Stone to postpone an Alaska canoeing trip. Stone’s orthopedist gave this advice to him and fellow authors: keep books you are signing at a uniform height. Hillary Clinton went further, protecting her health by taking a leaf from the world of politics and having some copies of It Takes a Village signed by a machine that reproduced her signature. Not content to limit this type of perk to politician-authors, Atwood spent years developing a device called LongPen that allows writers to sign books from the comfort of their own homes with a robotic pen as they chat with book buyers by remote video. Unfortunately, LongPen hasn’t caught on.

Some authors think it’s prudent to sign as many books as possible on the theory that booksellers are less likely to return such books, and book buyers to lend them. Perhaps not lend, but resell? It’s a rare author who hasn’t encountered an inscribed copy of one of his or her books for sale at a store, or worse yet, at a garage sale, or at Goodwill. Robert Olen Butler once spotted a novel of his on the closeout shelf of two-for-a-dollar hardbacks at a used-book store. To make matters worse, the book’s dedication page had been cut out, leaving only the recognizable swirl of Butler’s R for his first name. In a similar experience, when Eric Lax was asked to give an impromptu speech on Woody Allen while visiting the University of Colorado, Lax said he’d be glad to, but would do a better job if he had a copy of his biography of Allen to consult. No problem, the biographer was told; the university library had a copy. And so they did: one he’d inscribed to a friend.

Essayist (and former Scholar editor) Anne Fadiman calls this experience “a memorial to a betrayed friendship.” It’s all too common. When former Defense Secretary William Cohen saw a copy of his 1991 novel One-Eyed Kings inscribed to his friend Christopher Buckley for sale on the Internet, he called this to Buckley’s attention. “You got me,” was the humorist’s response.

The Internet provides many new opportunities to be embarrassed by old inscriptions. Now one needn’t even enter a bookstore to find inscribed books for sale. All it takes is a computer or a smartphone. When Googling their own name, authors are commonly dismayed to find how routinely online sellers of used books note inscriptions in their wares. While doing just this, I once came across a copy of a book I’d given to a former professor. As the online bookseller noted, my book’s inscription had this man’s name followed by the words “who taught me.”

The other night I dreamed I’d taken a job in Panama that required me to spend eight hours a day filling the front pages of books with inscriptions and drawings. I awoke in a cold sweat. Soon afterward I dreamed that no one showed up at a book signing arranged for me at the local library. To add insult to injury, a group of friends walked right by me, oblivious to my anguish. They were on their way to another author’s signing. Leaving my author’s table, I got in step with them, relieved to leave the ranks of signers, happy to become a fellow signee.