In ordinary times, a 10-episode documentary series about Michael Jordan’s final championship season with the Chicago Bulls, now more than 20 years removed, might seem, well, excessive, even if the subject happens to be Michael Jordan. For a sports fan who came of age when he was at the height of his powers (as I did), Jordan represented a kind of hyper-charged distillation of athletic greatness, his obsession with winning borderline pathological, his dominance so unrelenting, so absolute, his reign seemed inevitable, preordained even. But since winning his sixth NBA title in 1998, not much has happened to alter Jordan’s legacy, even if his image has softened in retirement. What’s left to learn?

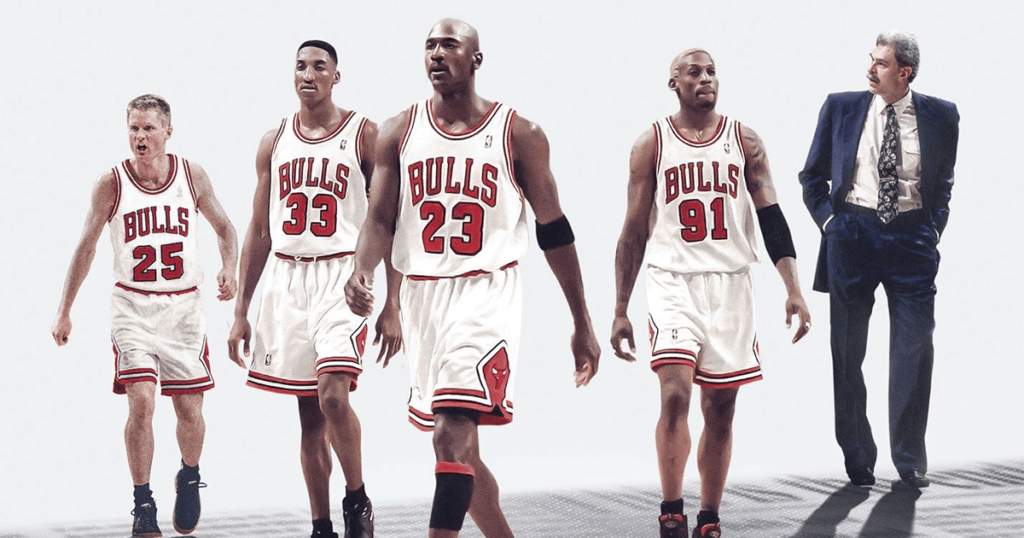

But these are not ordinary times. And so, taking a 10-hour plunge into the nostalgia-filled depths of the sporting archives is an invigorating if indulgent prospect. The first eight episodes of The Last Dance, which ESPN produced with Netflix Films, have now aired; the final two are slated for Sunday. There’s no real drama: from Jordan’s game-winning jumper for North Carolina in the 1982 NCAA national championship; to his early years with the Bulls, when he couldn’t win the big one; to the arrival of Zen-master coach Phil Jackson and the triangle offense, leading to “three-peat” number one; to the death of his father in a roadside robbery; to his notorious gambling issues, first retirement, and foray into baseball; to his return to the Bulls and his second three-peat, capped off with (what else?) another game-winning jumper against the Utah Jazz in the 1998 NBA finals—it’s all there. No real drama, that is, if you don’t count the feuds between aging superstars the series has reignited, the trail of ravaged souls Jordan left in his wake, or the Bulls’ internal politics, which might culminate with Jordan punching you in the eye (see Steve Kerr).

The effect is like opening a video time capsule from the recent past, the television graphics Atari-esque, the rap old school, the suits so baggy that a small child could go missing in them. Much of the action (off-court anyway) unfolds in locker rooms. A favored backdrop is the subterranean stadium passageway, when it’s not the team’s private plane or bus, or some nondescript hotel room during the midseason grind, where on one occasion we find Jordan puffing a cigar, relishing a few moments of relative solitude, and reflecting on how ready he is to leave all of celebrity’s attendant demands behind.

How many ways can you describe Jordan’s greatness, and how many talking heads can you get to do it? There are more than a few comparisons to god. The scope is staggering. We take brief detours into the lives of Jordan’s supporting cast, and just as we begin to get sucked in to the backstories of, say, Scottie Pippen, Jordan’s perennially undervalued sidekick, or Dennis Rodman, the flamboyant defender nicknamed the Worm, we zip back to the future with whiplash-inducing speed.

If I’m giving the impression that I haven’t much liked “The Last Dance,” let me assure you: I have been drawn to it like a Kardashian to a camera. The images flash by in a time warp of accumulating power. A young, lithe Jordan spending an inordinate amount of time levitating around the rim. Jordan, as part of the 1992 Olympic Dream team, announcing his supremacy by torching Magic Johnson’s side in a fabled intrasquad practice. Jordan gambling $20 with his security staff to see who could toss a quarter closest to a wall. Jordan mercilessly teasing general manager Jerry Krause about his height. A beret-clad Jordan exploring Paris during a 1997 exhibition tour. Jordan demonstrating, by way of some turnaround jumpers during the 1998 NBA All-Star Game, that the coronation of a 19-year-old Kobe Bryant as the next king would have to wait.

There was little expectation that the series would break much new ground, largely because Jordan had final say on the footage that aired. He was no Muhammad Ali when it came to leveraging his athletic prowess for some greater cause. He was a corporate brand with global reach, a direct precursor to Tiger Woods. “Republicans buy sneakers too,” is the line that endures—a quip that dates to 1990, when Jordan declined to endorse Harvey Gantt, the African-American former mayor of Charlotte, who was running for a U.S. Senate seat in North Carolina against Jesse Helms, a fierce opponent of the Civil Rights Act. There had always been some debate about whether Jordan actually uttered those words, but in episode five, he owns up to it—and expresses little remorse: “My mother asked to do a PSA for Harvey Gantt, and I said, ‘Look, Mom, I’m not speaking out of pocket about someone that I don’t know. But I will send a contribution to support him.’ Which is what I did … I never thought of myself as an activist. I thought of myself as an athlete.” Cut to Barack Obama, who in typical midseason form plays it right down the middle: “For somebody who was at that time preparing for a career in civil rights law and public life, and knowing what Jesse Helms stood for, you would have wanted to see Michael push harder on that. On the other hand, he was still trying to figure out, ‘How am I managing this image that has been created around me, and how do I live up to it?’”

What is revelatory about the series is how it has reminded me that Jordan’s greatness wasn’t inevitable. During his rookie season with the Bulls, we find him doing his laundry in his humble apartment, footage intended to humanize him that I found unexpectedly moving, in its portrayal of a young athlete with otherworldly promise, yes, but no knowledge yet of how things would play out. Even in the final championship season, things could have easily unraveled. Pippen wanted to be traded, Jackson was on his way out, and all the maneuvering by management led one reporter, the late Craig Sager, to ask Krause whether he was surprised the team was playing so well given all the backstabbing. (“There’s no backstabbing going on here, okay,” responds an irritated and flustered Krause, before calling the press conference to a premature close.) The series may be excessive in its scope, in its polishing of the image, but in the present moment it’s a welcome retreat, a chance to witness Jordan willing his teammates to champagne-soaked glory one last time, before exiting in a haze of cigar smoke, to a future that will struggle to measure up to the past.