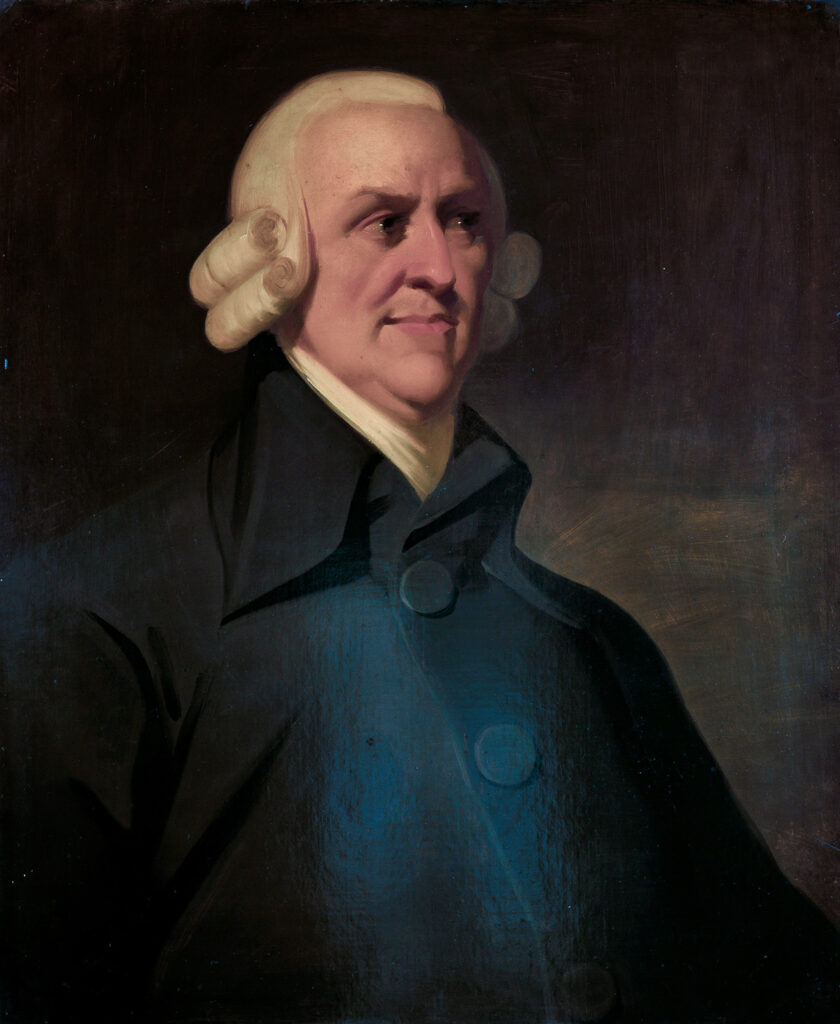

Today probably marks the 300th birthday of Adam Smith. We don’t know exactly when the Scottish philosopher was born, but records indicate that he was baptized on June 5, 1723, in the town of Kirkcaldy, a town just north of Edinburgh. While many of us know Smith as the author of The Wealth of Nations (1776), fewer are familiar with his earlier work, The Theory of Moral Sentiments. And even fewer know what Smith knew: that this book, published in 1759, is “a much superior work” to the later one that brought him fame.

Imagine that. No, seriously, imagine that. This is what Smith, after all, invites us to do in the book. The faculty of imagination is to Theory of Moral Sentiments as gravity is to Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica. For Smith, imagination is the activity that governs our social world no less surely than gravitation governs the physical one.

And so, let’s take a moment to celebrate Smith’s birthday by trying to imagine why he thought The Theory of Moral Sentiments to be the better book. Whereas he begins the work, in the provocative fashion that endeared him to his students, with a description of a man being tortured on a rack, we can instead begin with a man attending a club in Edinburgh. Not the sort of club given to drinking, though that certainly took place, but instead a club given to thinking.

Crucially, these clubs helped rebrand 18th-century Edinburgh. Long known as Auld Reekie—thanks to the stifling shroud of coal soot that rose from its forest of chimneys—the city became known as the Athens of the North. This was not a hollow claim. Though it boasted scarcely 40,000 residents, Edinburgh also boasted that it was, in the words of an observer, “crouded with men of genius” (Though as a walled city with tottering tenements packed together on wynds, or narrow streets, Edinburgh could hardly be anything but crouded.)

These men of genius, when not lecturing at universities like Smith, writing in their studies like David Hume, sermonizing from pulpits like Hugh Blair, or overseeing their estates like Lord Kames, met in clubs and societies to debate the great notions of that enlightened age. Between sips of claret and gulps of oysters (usually at the Oyster Club), they fearlessly prodded and poked one another (especially at the Poker Club) on the questions of human progress and the nature of being human. They weighed the gains and losses of technological, industrial, and commercial advances; they sought the sources of moral action and why we tend to be good when we could quite easily be bad.

The most select of these clubs was, inevitably, the Select Society. Conceived in 1754 by the portrait painter Allan Ramsay, it brought together the city’s best and brightest. Along with Hume and Kames, there was Blair, the Protestant minister who could “stop the hounds with his eloquenc”; Lord Monboddo, who wrote on the evolution of languages when not hearing cases as a judge; and that young “noddle-head,” as Hume called James Boswell. (“Bozzy” was admitted to the august society long before he published his biography of Samuel Johnson, who happened to think little of Scots and less of the Select Society).

Another founding member, also yet to become famous, was Smith. A professor of moral philosophy at the University of Glasgow—he commuted on the daily coach to Edinburgh for these sessions—Smith was decidedly the most remarkable figure in this group of remarkable men. He never spoke—at least to others. “The most absent man in Company that I ever saw,” recalled his friend Alexander Carlyle Smith was always “Moving his Lips and talking to himself, and Smiling, in the midst of large Company’s.” Indeed, he was often incapable of taking part in everyday conversation, Stewart noted, a man “habitually inattentive to familiar objects, and to common occurrences.”

It’s not that he was inattentive to the men in his midst. What Smith understood, perhaps better than most of his colleagues at the club, was how futile it is to gain access to the minds of those we meet. We are all strangers to one another not just in the night, but in the day as well. As Smith remarks, “we have no immediate experience of what other men feel.” This is both an undeniable and unsettling observation. Yet it is resolved, Smith contends, by two capacities we all share: sympathy for another person’s pain or happiness (expressed in the form of pity or joy) and imagination. To Smith, imagination picks up where fellow feeling leaves off. As Smith declares at the start of the book, we can form no idea of how another person feels “but by conceiving what we ourselves should feel in the like situation.”

Suddenly, imagination is no longer something we associate with children at play, but instead a faculty that all of use at every moment of our waking lives. In every encounter with a fellow human being, we call upon our imagination to try to know what they are feeling at a given moment. What we now call intersubjectivity is little more than the exercise of imagination with a dollop of fellow feeling. And perhaps another swig of claret.

But Smith has only begun to reveal how we become ourselves. His own remarkable imagination now careens in an unexpected direction: to the discovery that we employ our imagination not just to conceive of another’s feelings, but also to calibrate our appropriate response. When I encounter a fellow human being, my response to the individual’s conduct reflexively expresses my degree of approval or disapproval. In effect, I—or you, dear reader—weigh what Smith calls the “propriety” of the other’s behavior. As he writes, “I judge of your sight by my sight, of your ear by my ear, of your reason by my reason, of your resentment by my resentment, of your love by my love. I neither have, nor can have, any other way of judging about them.”

Of course, the person I am judging is at the same time busy judging me. Like me, the other will recoil if I show inconsolable grief; like the other, I will rejoice if that person displays an inspiring goodness. For Smith, morality rhymes with reciprocity: we gauge our behavior by “tuning up” and “tuning down” our emotions to achieve what Smith called the “pitch of moderation.” Here lies the mother vein of ethics: the degree of another’s compassion and caring is tied to my degree of the “awful virtues” like selflessness and restraint.

But what if the mirror offered by my fellow men and women is warped by instances of prejudice or ignorance? Do I then find myself abandoned with neither moral compass nor guide for my own actions? Not at all, Smith replies. When I cannot look to others, I can look to myself—or, more precisely, to what Smith calls the imaginary “man within the breast.” This “impartial spectator”—the compounding stock of my lived experiences with my fellow women and men—allows me to find a place, free of partiality, to properly gauge my actions. In a passage added near the end of his own life, Smith announces that “man naturally desires not only to be loved, but to be lovely; or to be that thing which is the natural and proper object of love. He naturally dreads, not only to be hated, but to be hateful; or to be that thing which is the natural and proper object of hatred.”

In a book chock-full of beautiful phrases, this is one of the most beautiful. But is it as convincing as it is inspiring? Three hundred years after Smith’s birth, we can only wonder. It is all too clear that our virtual world of information silos and social platforms threatens the credibility of an impartial spectator in the breast of each and every one. It is equally clear that ambitious individuals not only seek to instigate hatred, but also to invite it, and thrive not by exercising the awful virtues, but by acting in awful ways.

Yet, as Nobel Prize laureate Amartya Sen argues, Smith nevertheless offers us an invaluable standard. In an age of intensifying global warming and increasing disparities in material well-being, Smith’s ethical framework reminds us of the “relevance of other people’s interests—far away from as well as near a given society.” No less important, it insists on the “pertinence of other people’s perspectives” to prevent us from considering our own as the only perspective worth having. More prosaically, Smith’s model of social harmony might help us the next time we encounter a fellow human being talking to themselves in a tavern or a train. This alone is reason enough to send Adam Smith our best wishes—or, perhaps, our deepest sympathies—on his birthday.