Little Bowls of Colors

Writing in a foreign language can reveal secrets long buried in our mother tongue

Many languages use some form of the word mother to refer to a person’s first language—la lengua materna, la langue maternelle, Muttersprache—and rightly so. The first language we learn is generally the one our mothers speak. This may not be so obvious in monolingual families, in which both parents use the same language, but if each parent speaks a different one, the children in most cases will first speak the mother’s. The words mother tongue suggest that the relationship we have with the first language mirrors the mysterious alchemy of our maternal relationships. Just as the mother is our entry into the world and our first love, the person from whom we learn first meanings, the beacon and the guide, so is the language with which we first make sense of the world. There’s something almost supernatural in the way our mother tongue holds us in its grip. We’re usually unaware of its power unless we emigrate to another country. When that happens, we begin to miss its homey warmth and yearn for its recognizable rhythms and cadences.

We never know another language the way we know our mother tongue. We know it without knowing how we know it. With a foreign language, we have to see its skeleton, its hidden machinery, all those facets that most native speakers can ignore. It takes a long time before the letters or the sounds automatically conjure up the object the way they do in the native tongue. A mother tongue exists inside us with a completeness impossible to replicate in another language; it has its roots in our whole being. Canadian researchers have recently confirmed what previously was only intuitively grasped: people who leave the country of their birth in infancy and have no memories of the language they were born into retain the pathways of the first language in their brains. These findings prove how deeply ingrained in us the mother tongue is. The brain continues to remember what by other measures has been lost. The first language is also the one that Alzheimer’s sufferers lose last. A friend’s father, a professor of Romance languages, fluent in French, Italian, and Romanian, lost the ability to communicate in his acquired languages long before the disease began to rob him of Polish, his mother tongue.

Polish, my first language, was our daughters’ primary language, too, and they used it with each other and with me. In our home in California, my husband and I communicated in English, which they understood but spoke only when needed. But the typical scenario didn’t play itself out in their case. After they entered preschool, the public language of school and the outside world took over. Polish was gradually relegated to bedtime storytelling and reading, and to intimate and private moments between them and me. Today they treat it as their mother’s language while recognizing that English is their mother tongue. Our daughters never experienced linguistic displacement, so the shift from one language to the other happened painlessly and naturally. They still speak Polish, but with none of the ease, fluency, or versatility of their English. If they ever live in a foreign country, they will long only for English.

I started learning English in 1967, my freshman year of high school. I wonder if I would have developed a passion for it if it hadn’t been for my teacher, Mrs. B. She’d just earned an MA in English from the University of Warsaw and moved to our small town in the Mazurian Lake region. Young, attractive, well dressed, she stuck out among the older teachers. On the first day of school, she wore a pale green twinset, a pencil skirt, and high heels, the embodiment of elegance and poise. She had several other pastel-colored button-down sweaters, which we all thought must have come from England. Against the drab and gray background of communist Poland, she seemed like an exotic and colorful bird, bringing in a whiff of worldliness and culture. By the time we entered high school, we had already studied Russian for four years, but most of us hated it. With English, it was love at first sight. I immediately decided I would learn to speak it well. Before long, I discovered that it came to me relatively easily, and in no time I was Mrs. B’s best student.

I had no plans to major in English; I wanted to be a psychologist. But midway through my junior year in high school, I changed my mind. It may have been that I became more aware aesthetically and politically. Just as Mrs. B personified the grace and refinement I aspired to, English turned for me into a symbol of everything that was missing in Poland at the time. It promised an escape from the constraints of a provincial environment into the larger world that I knew existed. Once I decided to study English at the university, I bought a thick notebook in which I began to jot down words to memorize. When Jorge Luis Borges writes about studying a language, he makes a comment that sums up my own experience: “Each word stood out as though it had been carved, as though it were a talisman.” I learned each word separately, marveling at its alluring strangeness and hoping it would take root in my mind. Thanks to this approach, I was never confused by the idiosyncrasies of English spelling. But even though I’m a good speller, to this day I have a hard time writing down proper names someone else is spelling out loud for me. My brain just never made room for the sounding of the English alphabet.

I was admitted to the English department at the University of Wrocław after passing the entrance exams. All our classes were taught in English. We struggled to follow the lives of Pip and Rebecca Sharp or the complicated plot of The Importance of Being Earnest, but gradually novels, plays, and even poems rewarded our efforts. I remember traveling home for Christmas my freshman year and laughing out loud at some of the hilarious adventures of Mr. Pickwick, while other passengers in the compartment gave me funny looks. At that moment, I knew I was enjoying Charles Dickens the way I enjoyed books in Polish. Now and then, I had to use a dictionary, but that only slowed me down and didn’t detract from my delight.

When I got my MA, I could speak, read, and write in English at the level required for a teaching job. English belonged to my professional life and gave me private pleasure when I read. At that time, I had no inkling that several years later I would move to America and use this foreign language daily. In Poland, I was used to having names for everything, being able to find words in any situation, from small talk to conversations about ideas, expressing my thoughts naturally and easily. Suddenly language was no longer a reliable anchor. I wasn’t just troubled by the “paucity of domestic diction” for taking “the shortest road between warehouse and shop” that Vladimir Nabokov talks about. I had to redraft my conceptual map, relearn, and re-experience the world through and in my new language.

As I experienced important life events and crossed many watersheds here, I began to develop a voice in English. You can’t live in a foreign linguistic environment and not be affected by it. After some time, even those who try to resist the intrusion of the adopted language, for fear it might contaminate the purity of their native tongue, will discover that they haven’t remained outside its sphere of influence. Its tide begins to envelop you, its strains and patterns seeping into your conscious and unconscious mind. The Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert said in an interview that when he lived in a foreign country, inspiration came to him in that country’s language, and he subsequently had great difficulty writing in Polish. He didn’t know the new language well enough to try to write in it, but the possibility fascinated him. Engendering different perceptions and thought, another language can give us a powerful mental boost.

Writers who work in a language other than their mother tongue often feel the need to analyze their choice, dissecting it from many angles, mulling it over in private, and sometimes even offering public explanations. No matter what motivated them, geopolitics or personal history, they harbor misgivings—at least at first—about the artificiality of their decision. Writing, after all, arises out of our most intimate core. And what can be more intimate than our internal relationship to the language that exists in the deep parts of our psyche and is ours by birth? In his essay “To Please a Shadow,” Joseph Brodsky writes that when “a writer resorts to a language other than his mother tongue, he does so either out of necessity, like Conrad, or because of burning ambition, like Nabokov, or for the sake of greater estrangement, like Beckett.” Of the three reasons Brodsky gives, it’s the estrangement that I find most interesting. One may seek it intentionally the way Beckett did, but most often it arrives as an unexpected gift.

Some years ago at a translation seminar sponsored by Boston University, I heard the poet Rosanna Warren say that she urged the young writers in her classes to treat English as if it were a foreign language. She wanted to warn her students against the clichés that so readily spring to mind and hinder original thinking as well as to emphasize the importance of scrutinizing the linguistic boundaries within which native speakers function. Since English isn’t my first language, I have no choice but to follow that directive. Estrangement makes me more attentive and cautious, with none of the flippancy people often exhibit in their mother tongue. Joseph Conrad, the writer whose example is invariably quoted in such discussions, saw himself as “a coal miner in his pit, quarrying all [his] English sentences out of a black night.” I’m not saying that only foreigners have that experience—writing is demanding and grueling, and all serious writers treat language with awe and reverence—but foreigners don’t have to be reminded of that. Estrangement is part of their normal interaction with their new language. They’re acutely aware of its perplexities and never take it for granted. When I write in English, language moves to the forefront, the words coming from outside, as if they only were the source of meaning. I obsess about words, want to know their etymologies, pay attention to their strange provenances, and test where and how far I can go with them.

Another language may expose our linguistic inadequacies and vulnerabilities, but it can also serve as a protective screen. Dubravka Ugrešić, a Croatian novelist and essayist, is convinced that it’s easier to express pain in a language that isn’t ours. If while living in our native language we experience traumatic events, we are likely to relive the pain while writing about them in it. The nonnative language, on the other hand, will cause us less pain, create emotional distance, and allow for the indispensable aesthetic detachment. And when there’s no visceral, bodily connection to another language, we can become more daring and say what we would have never said in our mother tongue.

Something like that happened to me. English helped me open up. It’s true that American society has fewer taboos, but it’s the language that gave me the freedom I didn’t feel I had in my mother tongue. We may not think about it, but we live much more in a language than in a country. The Polish poet Ryszard Krynicki says in his poem “The Effect of Estrangement” that he prefers to read his own poems in a foreign language, since then he feels less the shamelessness of his confession. Broaching certain topics in Polish would have made me feel awkward if not ashamed; in English, it was similar to whispering my sins through a wooden lattice in the confessional. I knew the priest was there, but he didn’t see me and I couldn’t quite see him. My sense of privacy has changed, but not to the “tell all” extent. I simply began to feel that I could share things about myself and my life, and assume that my experience was worth talking or even writing about.

I grew up knowing you weren’t supposed to reveal information about your family to strangers. But this secretiveness wasn’t just related to political issues, something expected in a totalitarian state. Within our own family, people tended to sidestep fraught personal subjects. As a child, I was aware of things unsaid and of the silence that followed an inconvenient question. The message my family sent me overlapped with the message of society at large, where it was understood and accepted that family members’ misdemeanors—sexual transgressions, alcoholism—had to be covered up. Abuse was never discussed; neither was depression or cancer, as if silence would work its magic and make any problem go away. You weren’t supposed to dwell too much on yourself or mention your successes, because this was interpreted as bragging. If someone brought up some accomplishment of yours, the correct response was to play it down. By the time you finished elementary school, you had absorbed all the dos and don’ts, and knew better than to divulge your feelings. Talking about books, films, and ideas was fine because it could be done at arm’s length. And if your innate temperament tended toward introversion, as mine did, the general standards surrounding privacy could turn you into an even more reticent person whose articulateness could reveal itself only in certain subjects.

When I met my American husband, I was stunned by how freely he talked about his family life, about his father’s manic-depressive episodes, his grandmother’s stinginess, and about himself—his feelings, disappointments, dreams. He seemed to have no secrets while I harbored many. With English giving me protective camouflage, I gradually ventured out into the open. For a while, it seemed that the person speaking wasn’t exactly me and that I was playing someone else’s part. In time, though, I became comfortable in this new persona. I could talk frankly about things that until then had been off limits: my grandfather’s alcoholism and sexual indiscretions, my mother’s emotional remoteness, my failed first marriage. I stopped bottling up my feelings, frustrations, anxieties. I’m not saying that I am no longer reserved, only that my second language has helped me overcome some of my past reticence. That change has also affected the way I communicate with others in my mother tongue. I now share with them what I kept out of view before and tell things my American friends already know about me.

But English helped me get unlocked in more ways than one. Though in high school I toyed with the idea of becoming a writer, I don’t believe I would have begun writing had I continued living in Poland. It’s as if dislocation combined with a new language had freed my creative muse. I began translating—at first into English—and a while later I tried my hand at writing. After the initial period, when I felt as though I were trying to play a four-hand piano piece with two hands, writing in English soon began to feel as natural to me as writing in Polish had been.

As much as I dislike the word reinvent—it smacks too much of self-help manuals—my second language did reinvent me. If the idea of personal transformation is very American, then in the process I have assimilated some of the cultural gospel of my adopted country. The change I underwent was prompted by the change in my external circumstances, but the outward conditions ultimately led me to who I may have been all along. By peeling off the inauthentic layers in myself, I may have reached the hidden core of my innate disposition.

English has also transformed my relationship with my mother tongue, which I have left but not abandoned or betrayed. Thanks to English, I’m more aware and appreciative of Polish. I can go into raptures about its flexibility, about its almost endless possibilities of creating diminutive and augmentative forms, and about the ease of coining new words. In my role as a translator, I avail myself of and rejoice in its resources—the prefixes, suffixes, declensions and conjugations, gender-marked endings, perfect and imperfect tenses, all of which allow for prodigious inventiveness and creativity.

If Facebook had a question about our relationship with languages, my answer could only be: it’s complicated. My two languages have forged a singular alliance. They live parallel and independent existences. For many years, I was in the habit of instantaneously translating from English into Polish in my head, or the other way round, often asking myself how I would say this or that in the other language. I stopped doing that when I realized that one language no longer needed to be bolstered by the other. Now I try to keep them in harmony, not let them clash and contend for position. To keep both happy, I alternate my reading: a book in Polish usually follows one in English. I’ve noticed, too, that my internal conversations are often bilingual, shifting from one language to the other for no apparent reason.

The Polish poet Czesław Miłosz lived in America for well over 30 years, yet with the exception of a few prose pieces, he consistently wrote in Polish. He believed that changing our language meant we had changed or wanted to change our identity, which to him equaled betrayal on two counts. After the political transformations in the former Eastern bloc countries, the word immigration has lost some of the meaning it had at the time Miłosz arrived here; I use it for lack of a better term but see it more broadly as the desire to cross borders, a desire often motivated by the longing for change. Ideally, this results in the expansion of consciousness, not the loss of identity and language. Although I left Poland, I haven’t really left, just as when I leave the United States, I’m still here. In the age of the Internet, this is the experience of many people who live at the intersection of two languages and cultures.

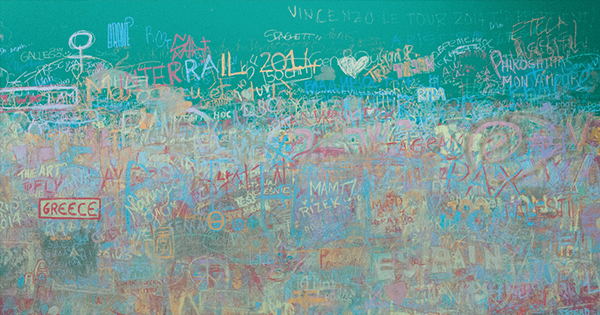

These days, each time I reread Miłosz’s “My Faithful Mother Tongue,” where he writes, “I will continue to set before you little bowls of colors / bright and pure if possible,” I’m reminded that I must prepare my own bowls of colors. But unlike the great poet, I set mine before my two languages: my mother tongue and another.