Who is the G.O.A.T., the greatest of all time? Tennis fans and pundits alike will consider that question anew now that Roger Federer has retired and Serena Williams has decided to “evolve” away from the sport. Chances are, if you’re a tennis fan, you already have strong opinions on the matter. Perhaps you believe that Federer, who elevated the game to a quasi-mystical level (David Foster Wallace famously likened watching him play to a religious experience), and Williams, who transformed the sport in her own way, are indeed the G.O.A.T.s.

Maybe you harbor strong opinions about the G.O.A.T.s in other sports, too: Michael or LeBron, Tiger or Jack, Marta or Mia Hamm, Brady or Montana, Taurasi or Swoopes. How would LeBron James have fared in Michael Jordan’s bare-knuckle NBA? Would Tiger have vanquished Nicklaus’s rivals—Gary Player, Tom Watson—golfers who didn’t fade into oblivion on the Sunday of a major? Did Lionel Messi, in delivering World Cup glory to Argentina, rise above Maradona and Pelé? These debates can make for a nostalgic trip into the sporting past, giving talking heads an excuse for ratings-driven histrionics. Witness the latest TV sparring over the newly retired Tom Brady.

But I’d contend that we’ve grown overly infatuated with bestowing G.O.A.T. status on our sporting heroes, and that this obsession has become a hollow sideshow, a lot of empty sound bites, signifying (almost) nothing. Forget that in its annual tongue-in-cheek Banished Word List, Lake Superior State University just called out “G.O.A.T.” as the most egregious for its “overuse, misuse, and uselessness.” The point is, there’s no way to compare players from different eras without resorting to wild speculation, and in most cases, a recency bias plagues these discussions—it’s almost always a player from this generation who wears the crown. When did we become so obsessed with this reductionist ritual, this anointing of the chosen one?

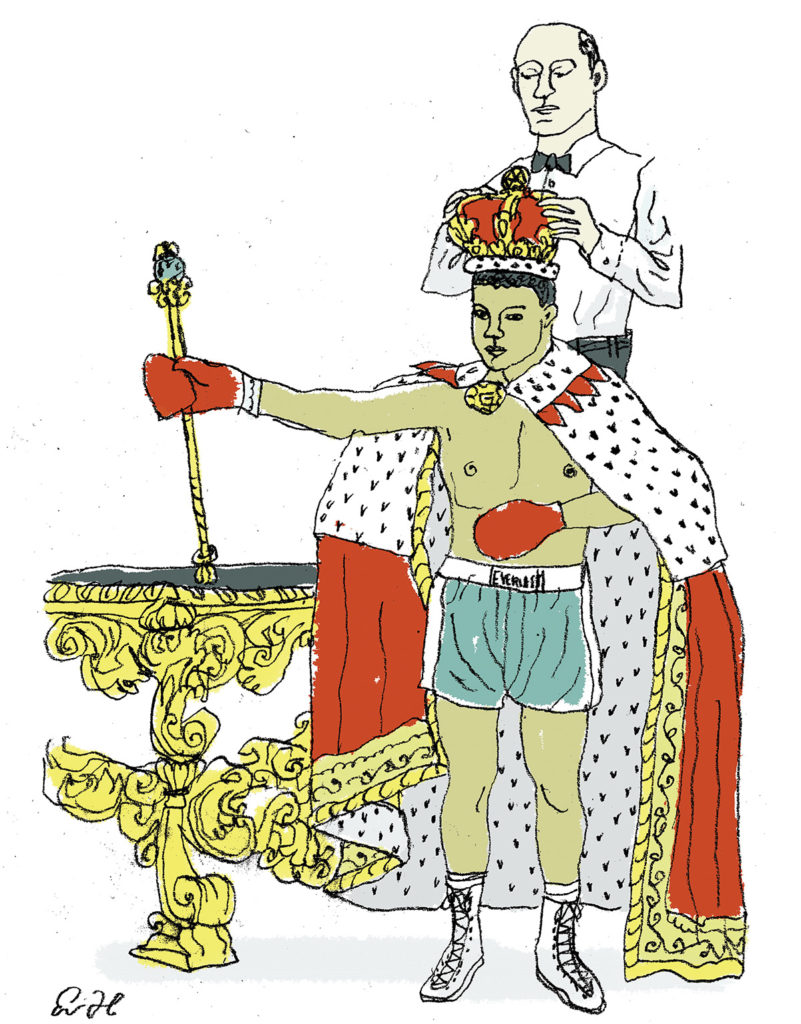

By nearly every account, we can trace things back to Muhammad Ali, who had no qualms about telling the world where he stood in boxing’s pantheon of champions. More specifically, according to Patricia O’Connor and Stewart Kellerman, authors of the Grammarphobia blog, we can pinpoint the debut of the acronym to September 1992, when Ali’s fourth wife, Lonnie, used the term “G.O.A.T. Inc.” to license her husband’s intellectual property. Rap and hip-hop circles were quick to catch on. “G.O.A.T.” appears in De La Soul’s 1993 track “Lovely How I Let My Mind Float,” and it arguably entered the mainstream in 2000, when L. L. Cool J dropped his album G.O.A.T.

On the sporting front, the first online use of G.O.A.T. occurred in 1996 on an Orlando Magic forum, as reported by Merriam-Webster, which added the term to the dictionary in 2018. “Penny [Hardaway] is the GOAT” is what history records. With all due respect to Hardaway, the former Magic point guard, this is but evidence that the moniker was meaningless from the beginning. G.O.A.T. mania spiked in February 2017, according to Google Trends, undoubtedly inspired by Tom Brady and the New England Patriots’ Super Bowl comeback against the Atlanta Falcons. It continues to infect nearly every corner of the sporting world: even Simone Biles donned a leotard with a bejeweled image of a goat on its sleeve. And after Serena Williams gave birth to her first child, her husband designed four billboards near Palm Springs advertising his wife as the G.M.O.A.T.: the greatest momma of all time.

As for the pundits now elevating Serena and Roger to G.O.A.T.-dom, how many of them saw Steffi Graf or Martina Navratilova play on Wimbledon’s Centre Court, let alone Rod Laver or Björn Borg? Pull up old YouTube footage of Wimbledon and watch Laver serve and volley with his wood racquet, his game predicated on touch and angles and placement, and be reminded that he was practically playing a different sport: no polyester strings, no outrageous topspin or bulging biceps, no access to contemporary training methods or nutrition, nothing resembling the intense physicality of today’s game. Rather, his matches have a garden-party feel to them, as if a couple of club pros were battling for bragging rights, before retiring to the pub for a pint.

Laver dominated his era, winning two Grand Slams and 11 majors. This, even though he effectively lost five years of his career because, after turning professional, he was shut out from the majors, which permitted only amateur players until 1968. How can one compare eras, draw meaningful conclusions about how, say, a time-traveling Laver—his physique newly buff, his racquet graphite—would fare against Federer at Wimbledon? The truth, of course, is that each successive tennis generation built on the accomplishments of the previous one, a kind of evolutionary cycle that continues, to this day, to reveal unimagined levels of the game—witness the recent arrival of a 19-year-old Spaniard named Carlos Alcaraz, who, having become the youngest world number one in ATP history, embodies the future of the sport. After Laver came Borg’s reign of dominance, which forced John McEnroe to dig deep to break through; and then McEnroe inspired Ivan Lendl to get superhumanly fit and usher in the modern power game, a magical era in which baseliners and serve-and-volleyers still coexisted: Pete Sampras and Boris Becker and Stefan Edberg pushing forward at Wimbledon, Andre Agassi and Jim Courier and Mats Wilander hanging back.

One finds a similar progression in the women’s game: Navratilova elevating the sport with her powerful athleticism at net, the intensity of her rivalry with Chris Evert foreshadowing the one between Monica Seles and Graf. Never mind Graf’s forehand; it was the German’s mental fortitude, says Serena, that inspired her as she reshaped the game into what we know today. In remembering the players of eras past who had a profound and transformative effect on the sport, who helped remake it in their image, an abiding fact emerges: none of them won majors much past their early 30s. Borg retired at 26 with 11 slams; Laver and Sampras won their last at 31; Graf was 29, Navratilova 33. Compare that with the current era. Serena won her final major at 35, Federer at 36. Novak Djokovic (at 35) and Rafael Nadal (at 36) seem poised to add to their total. Much of the apparent statistical dominance exhibited by players today, therefore, is based on their longevity, which in turn is based on the advances made in fitness and nutrition—yet another reminder that it’s all but impossible to compare generations without resorting to fuzzy math and biases born of recency (or nostalgia).

Before the arrival of the acronym, “greatest of all time” was, according to a search of historical newspapers, applied to all manner of athletes in the prewar era, but unfailingly with an extra word thrown in: among the greatest of all time. A caveat. A qualifier. Which may offend someone with the sensibilities of baseball’s Ted Williams, who was never coy about his desire to be the greatest hitter who ever lived, but which otherwise seems to be enough of a rarefied designation to make the need for further classification seem, well, a bit Type A American. As for Muhammad Ali, much of his “greatest of all time” banter was shtick—part personal motivation, part psychological warfare, part business strategy: “I like to be the villain,” he once told the Irish journalist Cathal O’Shannon. The allure of G.O.A.T. is the pleasing clarity, the idea that one player is the undisputed best, the finest manifestation of sporting greatness, with a certain tribalism infecting the debates—you’re either team Federer or team Nadal, for instance. But of course, as in life, there’s no real clarity, no reassurance that your best years are still to come, or aren’t already behind you.

If you remain intent on ranking athletes, I will grant you this: the rubric should be framed around not who is the greatest of all time, but who is the greatest of a particular generation, which doesn’t much lend itself to the acronymic tidiness of G.O.A.T.—or the title of a rap album. But it’s a more reasonable lens through which to view the current debate over, say, Roger, Rafa, and Novak. Does Rafa’s claim hinge too much on his dominance on clay (14 French Opens)? Will Novak’s Covid vaccine stance, which caused him to miss two majors last year (but didn’t prevent him from winning this year’s Australian Open), hurt his numerical case? Did Roger get tight and choke away a couple finals, undermining his claim? Have at it.

But also remember that even this debate doesn’t adequately explain why the recent golden era of tennis mattered so much—not only to the fans but also to the players themselves. Here’s Federer, back in 2012, after winning Wimbledon, on the possibility that Nadal might one day surpass his slam total: “If he does beat my record, it almost doesn’t matter. Because I did things he can never do. He did things that I can never do. It’s the moments that live and the memories that are with me that are most important.”

In his final match, at the Laver Cup last fall, Federer lobbied to play not singles but doubles with Nadal, a symbolic gesture that emphasized how their rivalry, one that had pushed them both to extremes on the court they could never have achieved alone, had also created a lasting friendship. They held a match point before losing to Jack Sock and Francis Tiafoe, but the result in the end mattered little. In classic Federer style, he had orchestrated a celebration of the game itself. On hand were Rod Laver, John McEnroe, Stefan Edberg, Jim Courier, and Novak Djokovic. Nadal, meanwhile, appeared to shed as many tears as Federer himself when it was all over. Never mind our G.O.A.T. infatuation: this spectacle was a reminder of how each generation has built on the previous one, and how in this most individual of games, it is your opponent across the net who makes everything possible. Federer stepped into the spotlight one last time, and then retired into the shade, to wait for the next generation to assume the crown.