Norman Maclean and Me

Advice for living and drinking from the author of A River Runs Through It

When I was a teenager, I flew out to western Montana from South Carolina to spend the summer with my brother John and his family in Seeley Lake, a small town near the Mission Mountains. John was a forester with the U.S. Forest Service. Marilyn, my sister-in-law, was being treated for breast cancer. My job was to drive her to Missoula, 52 miles away, for radiation. I was also supposed to babysit my niece, Meg, who was two.

My second Saturday in Seeley Lake, we were going out to dinner with Professor Norman Maclean, a widower friend of John’s who taught English back East. In the Forest Service compound where we lived, everyone already knew our dinner plans. Norman was a summer person. Most year-round Montanans didn’t mix with the summer people, an affluent group that arrived in June and stayed until early fall, enjoying cabins built decades before on the federally owned lakefront. But my brother did. Part of his job was making sure all was well with these temporary residents, some of whom, like Norman, were lonely. He and John swapped stories about the early Forest Service, talked about alpine wildflowers, and bonded over their shared dislike of the “loud bastards” from Great Falls who took over the nearby campground, leaving the trashcans overflowing and the outhouses a mess.

We stood in the living room of John and Marilyn’s cabin, ready to drive to the Seven-Up Ranch restaurant in Lincoln, 54 miles away. Logging a hundred miles for a good meal was normal in Montana, where at the time there was a speed limit only at night. Norman arrived at my brother’s cabin promptly at six, driving a boxy Volvo sedan. It was the first Volvo that I, or probably anyone else in Seeley Lake, had ever seen.

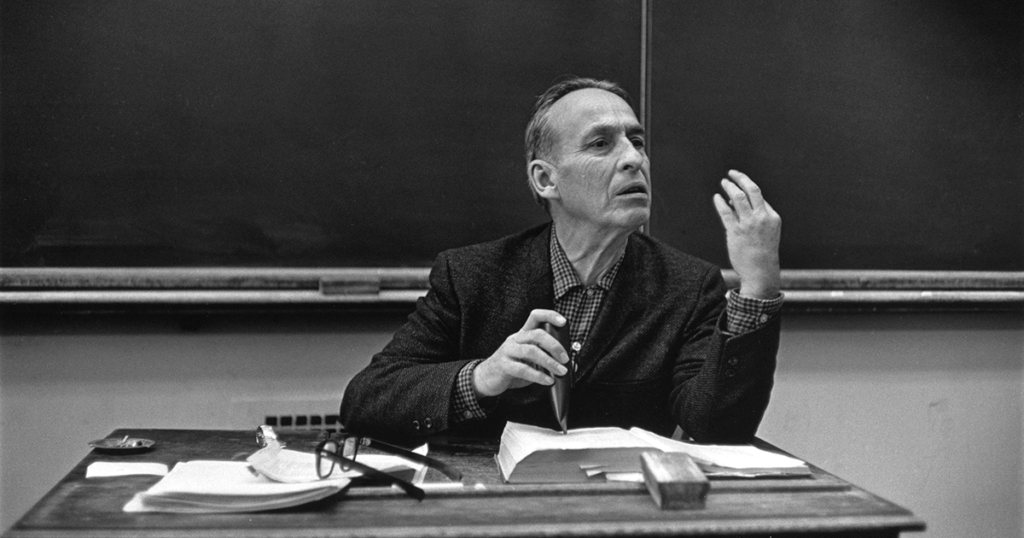

Holding my niece on my hip, I watched through the window as Norman got out of his car. He was a compact older man with high cheekbones and a slight scowl. He hiked up his pants and smoothed his dark hair as he looked around the yard at Meg’s upturned toys. He wore corduroy pants, a denim shirt, a plaid tie, and a windbreaker.

My brother opened the front door as Norman climbed the porch steps. He smiled up at John, who towered over him, and they shook hands. Norman kissed Marilyn on the cheek as he walked through the door. I stood behind her, jiggling Meg to quiet her. I smiled.

“Rebecca, darling, this is a great pleasure,” he said. He nodded at me, and I nodded back.

Norman suggested that we take his Volvo. John, Marilyn, and Meg could sit up front, Norman said, and he and I could sit together in the back seat and talk. As I climbed in the car, I wondered what we would talk about. Would he quiz me on 19th-century Romantic literature? Or Shakespeare?

We didn’t say anything until John turned onto the highway.

“What’s on your great mind, dear?” Norman began.

What was on it? What mind? I was blank.

He drew some papers out of a pocket in his windbreaker. There was writing all over them. Most of the writing was mine. I felt nauseated when I realized that these were poems I had sent to Marilyn, the traitor in the front seat.

Norman laid the papers in his lap and began to talk to me about my poems, telling me things I had never noticed about their rhythm and language. While John and Marilyn entertained Meg with songs, Norman and I talked about poetry. The questions he asked were ones I could answer, the poems ones I had read. I had never had an adult take me so seriously.

At the Seven-Up Ranch, John, Marilyn, and Norman sipped Scotch before the meal. I asked for a Tom Collins. In those days, I believed a good drink was multicolored, sporting little umbrellas, orange slices, and cherries on swords, the more colors and weaponry, the better. Norman glanced at the tall glass, raised his eyebrows, and pursed his lips like he might whistle, but he didn’t say anything. I didn’t drink much of it, but I saved the little umbrella.

After we had eaten steak and potatoes, Norman leaned across the table toward Marilyn, who was sitting next to me. He frowned. “Are those bastards killing you to cure you, darling?”

Marilyn smiled. “No, Mac, they’re not. I’m just tired, that’s all.”

He raised his eyebrows and gestured with his head toward me. “Rely on your sister-in-law there. She’s young and tough, and she can help out.”

On the way home from the restaurant, Norman asked me about college. Where would I go? What did I want to study? I didn’t know where I wanted to go, I said, maybe to the university in Missoula. Marilyn and I had eaten lunch there before one of her radiation treatments, and it seemed like a comfortable place. He ignored this idea and suggested that I think about Chapel Hill, Duke, or the University of Chicago, where he had taught for decades. “Fuck it, Rebecca,” he said, and told me I should leave the South. I was glad it was dark outside, because I was blushing.

“Chicago’s the big leagues, darling, but I think you could handle it. You’re a strong, powerful woman.”

Until then, no one had ever referred to me as a woman, much less a strong, powerful one. I felt older just hearing it and decided I would think of myself as a strong, powerful woman from then on.

“You haven’t met her mother,” Marilyn said from up front. She held a sleeping Meg on her lap and leaned against my brother. “You’ll have to get past her.”

Late one afternoon a week or so later, John and I were riding around Seeley Lake when we turned down the narrow driveway to Norman’s cabin. John made a habit of checking on the older summer people, and today was Norman’s day.

The cabin was on a knoll overlooking the water. There were tamaracks all around it. As we approached the door, I could hear someone inside humming. Before John could knock, Norman opened the door, smiling, inviting us in. He stepped into the kitchen, took the lid off a Crock-Pot, and stirred whatever he was cooking, releasing a delicious, meaty aroma. He herded us onto the screened porch, then disappeared, humming as he walked. A few minutes later, he returned with two tumblers half full of something brown, handed one to John and one to me, then went back inside for his glass. He sat down in a chair near me and began to talk.

“Rebecca, this is Scotch on the rocks. Before dinner, you can drink Scotch or bourbon, with ice or water or club soda. With a twist of lemon in the Scotch if you like. Or you can have a glass of sherry.

“A Tom Collins, a gin and tonic, those are drinks for you and your boyfriend after a game of tennis. Not before a meal. With food, you can have wine. And after a meal, you can have another glass of Scotch or bourbon. Or a sherry. Or a cordial, maybe brandy. That’s it, darling, those are your choices.”

I looked at the Scotch in my glass. I was 16, and I had never had a real drink. The Scotch smelled and tasted like lighter fluid, but I managed to swallow a little without choking. It went straight up my nose, setting my nasal passages on fire. Norman was complaining to John about some clear-cutting bastard who needed his testicles removed. From my brother’s response, I realized that the bastard was the ranger who lived next door to us, who I had thought was a nice man. I looked around the porch. There were two beds against one wall and a few chairs and tables. I drank some more Scotch and closed my eyes, then opened them and gulped down the rest of the drink.

“Rebecca, darling, I’ll get that,” Norman said as he took my glass away. He soon returned with more Scotch. I made it about halfway through the second drink before getting up and lying down on one of the beds.

When I woke, I smelled wood burning. Far away I could hear John and Norman talking about those early days of the Forest Service. I shivered and tucked my legs under a blanket someone had draped over me. I opened my eyes and saw that dusk was dwindling into dark, so it must have been close to nine. Loons were calling. They sounded too hysterical to get their songs out. My mouth felt full of cotton, and my temples were pounding.

“John?”

He appeared at the bedside and handed me a glass of water. I drank and felt better. He said it was time for supper, that we were staying and eating with Norman. We wouldn’t be home for dinner because I’d had an accident.

“What accident?”

“You ran into a wall after drinking too much Scotch.”

I could feel myself blushing, but my brother ignored it. He helped me sit up and led me to the table where Norman was sitting. There was stew on each of the three plates and glass tumblers at two. Smaller plates held pears and cherries. A fire was burning in the fireplace. Norman looked up at me.

“Your big brother here has promised to warn me of your next visit so I can have enough Scotch on hand.” Norman grinned and shook his head. “God, woman, I tell you the proper way to drink, and you drink. I’m just glad I didn’t tell you about rock climbing or grizzly hunting.”

I was sure strong, powerful women could drink Scotch without feeling woozy.

“Sit down, dear, and eat.” He pointed to the place with no glass. “We have stew and some wonderful Bing cherries for dessert. But I’m not giving you any wine.”

Everything seemed to slow down with Norman. Maybe he and John had continued drinking Scotch after I had gone to sleep, and were a little tiddly. Maybe he always ate bite by bite. Whatever the reason, we were at that table for two hours, listening to Norman tell stories about a book he was writing about his brother and about his own decision to go east to college.

Norman had grown up in Montana and graduated from Missoula County High School. At his mother’s kitchen table, he said, he had completed written exams from different colleges. He mailed them all back. Weeks passed. Several schools, including Harvard and Yale, accepted him. He eventually chose Dartmouth. When it came time to go, he said, he cleaned his best shotgun, packed his clothes, and got on the train in Missoula, heading to New England.

At Dartmouth, he had edited a humor magazine, boxed, and been friends with Ted Geisel, the creator of the Dr. Seuss books and “the craziest guy I ever met, darling.” Norman had also taken money from “a lot of rich bastards” at the poker table. He smiled from ear to ear at the memory.

“But the East isn’t the place for you, Rebecca. The Ivy League is filled with rich men’s sons and daughters. Old money. Secret societies. Joe College. Bastards.”

He shook his head and hissed, “Sssstttt.” The sound was a cross between a punctured tire and an angry rattlesnake. “No, Chicago’s the place for you, darling. A strong, powerful woman like yourself, a poet, they would love you.”

The part about the school blew right over me. What I heard was that Norman considered me a poet. When an adult names you, before the wax is completely dry, the name becomes part of who you are.

“I don’t know what our mother will say about my baby sister going to Chicago, Mac,” John said, repeating Marilyn’s warning. He leaned back in his chair. “Could be a hard sell.”

“You can handle her, John. I have confidence in you. You don’t want any small-town provincialism wrecking Rebecca’s chances just as she’s starting out. And neither do I.” Norman drained his glass and poured some more wine.

“You can’t stay here, Rebecca.” He turned to look at me. “You would end up married to some piss-fir willie with too many children and no time for poetry. I decided to leave Montana by asking myself, ‘Who would you talk to if you stayed here? And what would you talk about? Fishing?’ I would have died. I needed to live in the world of ideas, and so do you.”

Although today I don’t have much time for pondering, as a teenager I did. I pondered his words during the rest of the summer at Seeley Lake. I took them with me when I went back to South Carolina for my last year of high school, and pondered them again when Norman’s letters started to arrive. Expert fly-fisherman that he was, Norman had hooked me at Seeley Lake. He spent months, in letters and phone calls, landing me. Ultimately, I decided that he was right. The next fall, I headed north to the University of Chicago for college—after my mother agreed. She did so, I knew, only because Norman had promised to take care of me. Despite her charm and beauty, my mother really was a tough customer.

In getting to know Norman, I got to know myself, at least a little. What he hoped to do for me and for all the young people he taught, he said, was to “help bring forth the best that’s within you,” whatever those gifts might be. He had spent more than 30 years figuring out how to talk about his brother’s death before writing A River Runs Through It, the book that would make him famous. At least a part of his early life in Montana was settled. But now, in his 70s and newly retired, Norman was still struggling to understand himself. “I want to know just who the hell I am, darling,” he would say to me, and that was comforting to hear. If someone as wise and wonderful as Norman questioned his identity, wouldn’t it stand to reason that I, a 17-year-old, would wrestle with similar problems? And that the process of knowing myself would unfold over a lifetime?