One Man’s Trash

In the windswept California desert, Noah Purifoy sculpted a visionary monument from the detritus of everyday life

In the high desert around Joshua Tree, along a dirt road that cuts through the hardscrabble landscape like an arrow, is a museum of otherworldly beauty—a miniature 10-acre city constructed of toilets, used tires, antiquated computers, old stoves, scrap metal, and other bits of salvaged junk. During the last 15 years of his life, until his death in 2004 at the age of 86, Noah Purifoy lived in a trailer on the site and created these installations and sculptures. Purifoy was no eccentric recluse but rather, in the words of Los Angeles Times critic Christopher Knight, “the least well-known pivotal American artist of the last 50 years.” Knight was reviewing “Junk Dada,” a 2015 retrospective of Purifoy’s work at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). The show contributed to the artist’s rediscovery, and since then visitors have flocked to the desert to see the coda to his career—the Noah Purifoy Desert Art Museum of Assemblage Sculpture.

I’ve come late on a Saturday afternoon in June. The tours are self-guided, and the donation box, recently broken into, has been replaced by QR codes that can be used to donate to the Noah Purifoy Foundation, which manages the museum. An eerie quiet prevails. The only sounds I hear are the buzzing of a few flies and the popping of some scrap metal expanding in the soul-sucking heat. Then, others arrive: a mother with two children, a couple with a dog, a landscape architect from San Francisco who tells me that the site reminds him of something out of Italo Calvino’s novel Invisible Cities. “We have to stay here until dusk!” he implores.

In the open-sky desert, the collection contributes to a kind of sensory overload. A Quonset hut, its doors intricately decorated with pieces of scrap metal, calls to mind Lorenzo Ghiberti’s north doors of the Florence Baptistery. Ode to Frank Gehry is a massive model, mounted on stilts, of a building constructed from white shipping containers and wood, the various planes colliding with Gehry-esque abandon. Spanish Arches, a ruinous structure made from carved slabs of stone, looks like something from Pompeii. The installations, more than 30 in total, reveal themselves as if in some fever dream, their range and ambition astonishing.

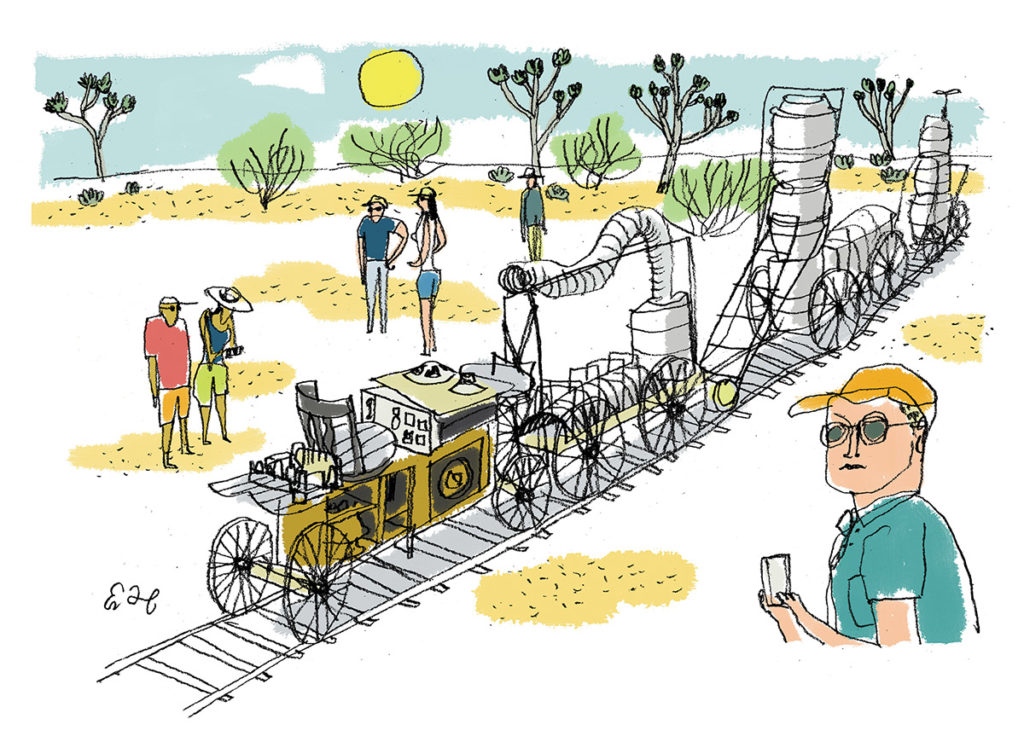

Some works come with a wink, a nod. The Kirby Express, a sprawling train made from bicycle wheels, broken vacuum cleaners, and keglike containers, occupies a track to nowhere. Others are more menacing, including the wooden Gallows, which pays homage to the bygone bravado of the Wild West. But it also seems of a piece with another work at the site, one that inspires no ambiguity: a small bus stop–style shelter containing a water fountain on one side and a toilet on the other, the sign above the fountain reading “WHITE,” the sign above the toilet reading “Colored.” Purifoy, a Black man who came of age in the Jim Crow South, disliked the label “Black artist” and insisted that his wasn’t an art of protest. Yet the message is as subtle as a hammer blow.

Born in 1917, in a small town outside Selma, Alabama, Purifoy served in the Navy during World War II and became a social worker before deciding to pursue art. He was the first full-time Black student to enroll at the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles, earning his degree in 1956. “I was the worst student in the whole school,” he once said. “I refused to draw, because I felt I had something and that if I learned to draw I’d be dead, because I’d end up making oil paintings, which wasn’t what I was after. I wanted to find my own way in art.”

In 1965, during the Watts riots in L.A., he found his own way. He recalled watching the burning and looting with the artist Judson Powell: “And while the debris was still smoldering, we ventured into the rubble like other junkers of the community, digging and searching, but unlike others, obsessed without quite knowing why.” He and Powell collected three tons of burned material, including the melted, jewel-like remains of neon signs from various storefronts, and joined with an interracial group of artists to produce 66 sculptures. The resulting exhibition, “66 Signs of Neon,” traveled the country, earning its share of critical acclaim.

The experience transformed Purifoy, according to Yael Lipschutz, one of the curators of the 2015 LACMA exhibition: he got “rid of his suits—[got] rid of all his excess material belongings—and imposed upon himself a life of poverty.” Purifoy was influenced by Marcel Duchamp and the Dadaists, the philosophers Martin Heidegger and Edmund Husserl, Simon Rodia (the Italian laborer who constructed the Watts Towers out of scrap metal and other found objects between 1921 and 1954), and Black folk art and African sculptural traditions. He embraced the socially charged possibilities of junk art, exhibiting his work at LACMA, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Brockman Gallery in Los Angeles, among other places. But he increasingly bristled at the way the art world catered to a privileged and moneyed elite and began experimenting with ways to use art to effect social change. In 1976, Governor Jerry Brown appointed him to a new agency, the California Arts Council. Purifoy took art programs to prisons, hospitals, schools, and senior centers, foreshadowing the community work by present-day artists such as Theaster Gates and Andrea Zittel.

A decade-plus later, newly retired and motivated by the idea of doing land art—but priced out of the L.A. market—Purifoy accepted an invitation from the artist Debby Brewer to set up shop on a plot she owned in Joshua Tree. He wasn’t particularly enamored with the desert—it spoke to him of “desolation and sheer poverty”—but he soon embraced the idea of leaving everything behind and spending his final years in service of all the work he had left in him.

He once spoke about his “beefs” with the art world: the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, he said, “is inclined to show Edward Kienholz. I’ve been equal to Kienholz ever since I started out, but they never decided to show my stuff. … [H]e’s white and I’m Black. That’s the difference.” But, he also said, “I’m not angry about anything anymore.”

That the museum survives today is no small achievement, in part because Purifoy himself was agnostic about its fate: “I don’t do maintenance. I do artwork,” he once said. “If it wants to deteriorate, I find some kind of gratification in watching nature participate in the creative process.” In 2001, local officials red-tagged the site as an eyesore and a potential safety hazard, according to Joseph Lewis, the long-standing president of the Noah Purifoy Foundation and a professor at the Claire Trevor School of the Arts at the University of California, Irvine. The foundation worked with the local land-use commissioner to clean up the trash and resolve code issues, leading to the site’s preservation.

As the visitors have come, so too has the surrounding development, with a pandemic-inspired real estate boom in Joshua Tree attracting Angelenos and other urbanites and displacing some local residents. The most prominent addition, just north of the site, is a red flying saucer–like structure called the Area 55 Futuro House, an off-the-grid “glamping experience” available for $292 a night on Airbnb. More than ever, Purifoy’s creation stands like some defiant outpost against gentrification and the encroachment of the market-driven art world he left behind in L.A. Shelter, which he constructed using salvaged wood from a neighbor’s burned house and outfitted with a ramshackle cot and an old television, evokes the housing crisis, both past and present. “If you remember Reagan as governor of California, he threw all the crazy people out into the streets,” Purifoy said in a 2002 interview. “I was a social worker at the time, and it struck me very seriously. So this is a political statement. … No, it’s a social statement.”

Purifoy never ascribed an environmental motivation to his art—“there’s no ecological message behind my use of recycled materials”—but standing there in the desert, I can’t help but think that Shelter, with its apocalyptic aesthetic, and Carousel, its collection of old computers and fax machines suggesting a place suddenly abandoned, are a clarion call to the threat posed by climate change. It’s hard to look at these works in their setting and not ponder our fate as drought and rising seas and unchecked capitalism conspire to make more and more of our planet uninhabitable. Combine that with the foundation’s ongoing attempts to preserve Purifoy’s decaying work, and there’s a feeling of urgency here, of standing on the verge of losing something precious.

But it’s the haunting beauty that carries through the whole of the site, the unexpected juxtapositions of everyday items that stir the imagination and all but command you to revisit your relationship to art and the castoffs among us. Here is the sweeping artistic vision of a man who spent his final years in a windblown and hostile landscape, creating a singular world that was the culmination of his outsize creative ambition. After his uneasy dalliance with an art world that had contributed to his share of disappointment, he gained a measure of salvation here.

“I should never have imagined a city like this could exist,” Marco Polo tells Kublai Khan in Calvino’s Invisible Cities. And I should never have imagined a museum like this could exist. I find a spot in the shade, my body alive with emotion, and wait for dusk.