Foursome: Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe, Paul Strand, Rebecca Salsbury by Carolyn Burke; Knopf, 432 pp., $30

This is the story of four talented people: Georgia O’Keeffe, Alfred Stieglitz, Paul Strand, and Rebecca Salsbury, who met by chance and remained involved with one another for the rest of their lives. Rather like partners in a quadrille, that 19th-century British craze and forerunner of the square dance, they bowed, circled, advanced, retreated, formed new patterns, and incidentally brought further perspectives to the often-told story of their lives. This latest attempt was made possible by newly available collections of letters, the raw material for Carolyn Burke, widely admired for her portraits of Mina Loy, Lee Miller, and Edith Piaf.

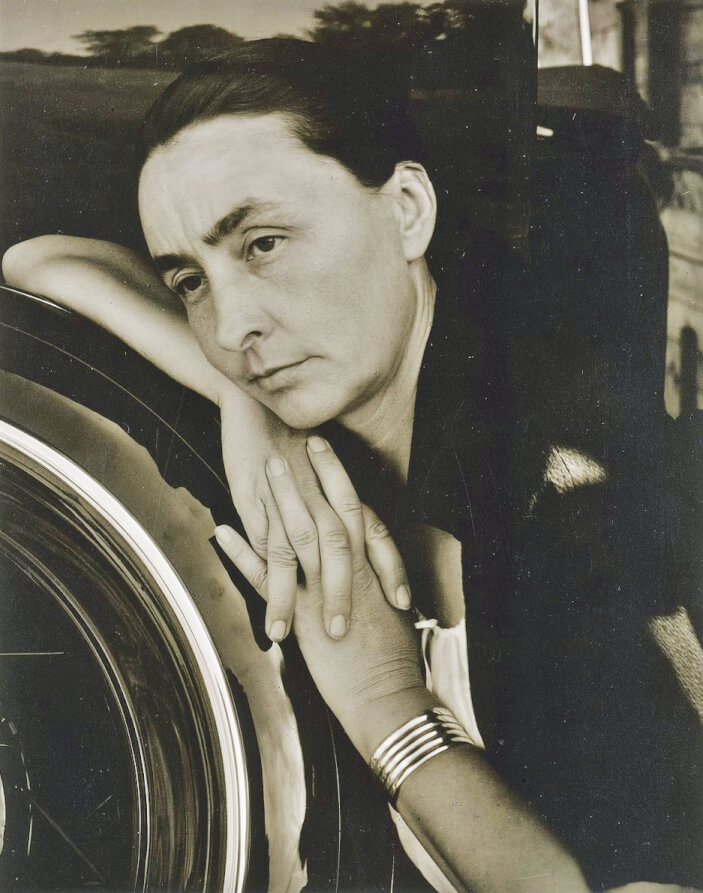

There is, of course, nothing new in the history of artists’ forming close relationships and influencing each other. Modigliani had Chaim Soutine and Ossip Zadkine. Gauguin had Van Gogh, and Mary Cassatt had a lifelong friend and mentor in Edgar Degas. What is unusual here is the durability of the friendships, which lasted despite major differences and geographic isolation. This tight little circle formed around a mentor, the photographer Alfred Stieglitz. Early in the 20th century, he was in the advance guard of artists who realized that America was far behind Europe in its ponderously academic approach to the arts.

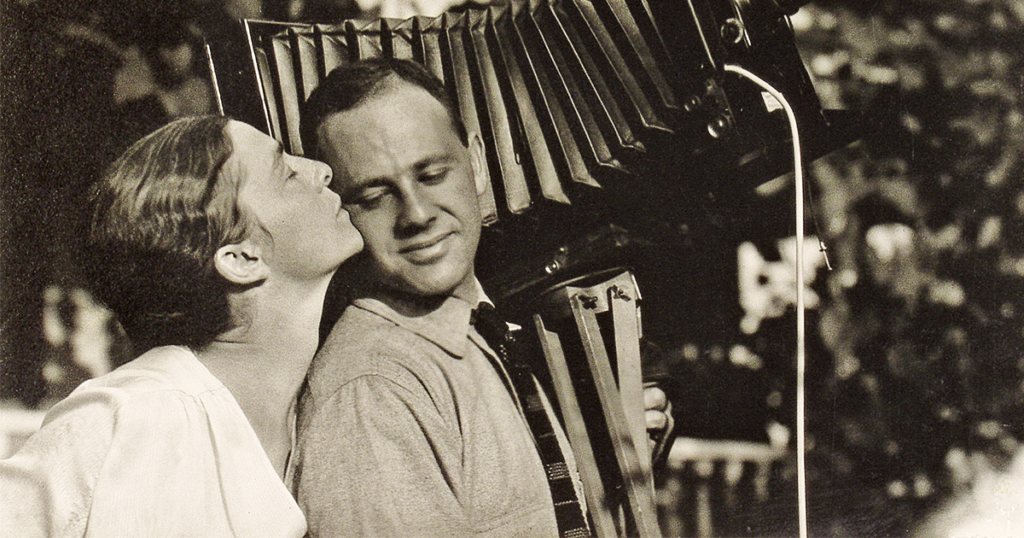

Georgia O’Keeffe, photographed by Alfred Stieglitz in 1933 (Wikimedia Commons)

Stieglitz, spurred to action, opened a tiny attic space in New York that developed into 291, the gallery that showed not only his own work but also that of the new modernists—John Sloan, George Luks, and Maurice Prendergast among them. Then Stieglitz joined the movement to bring the best Europeans to the United States, which resulted in the historic 1913 Armory Show in New York. Among the 1,000-plus paintings and sculptures on view were works by Léger, Redon, Seurat, Cézanne, Matisse, and Picasso. Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, with its multiple superimposed images, is often cited as the single most dramatic representation of the audacity of the new directions. The years 1910–1913, Meyer Schapiro wrote in Modern Art, were “heroic … in which the most astonishing innovations had occurred.” Stieglitz was right in the middle of what was happening.

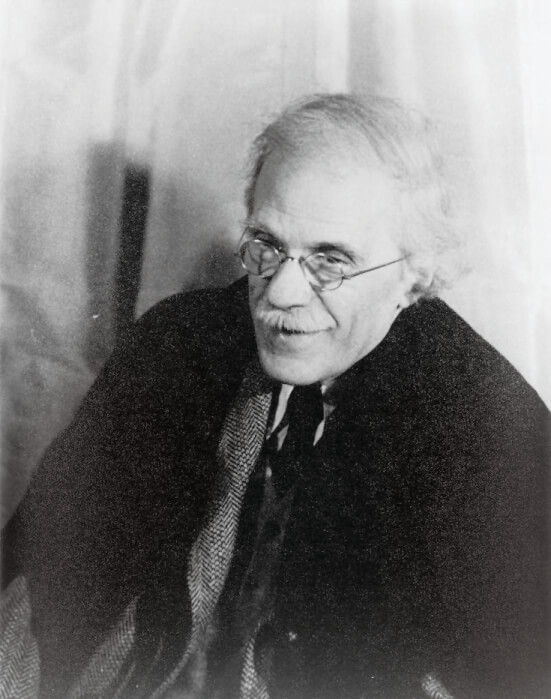

Paul Strand, who was getting his own start in photography, was the second to appear. He had also been influenced by the Armory Show and became a passionate follower of Stieglitz’s ideas, the first of which was to take his camera outside and capture life on New York’s streets. After showing his work to Stieglitz, Strand was accorded his first major exhibition at 291, and he became, for a time at least, Stieglitz’s most devoted admirer.

Any group heralding a radical departure from the norm will face entrenched resistance, and the new modernists were no exception. United in the revolution that took a long time coming, they eagerly concerned themselves with the idea of social progress, particularly the loosening of sexual mores. This was when Georgia O’Keeffe joined the group. At a moment when most women’s roles were limited to marriage and motherhood, O’Keeffe’s sense of herself was bound up in her goals as an artist.

Not that she turned her back on the opposite sex; quite the opposite. O’Keeffe quickly replaced her first boyfriend, named Arthur, with Strand—all of them were remarkably casual about things like that. Stieglitz was married at the time, but this did not prevent him from kissing the cook and anyone else who got too close. Naturally, he was entranced by the distinctive looks of the new arrival, not to mention her body, and she was perfectly ready to take her clothes off. Altogether, Stieglitz took some 250 photographs of O’Keeffe, those in the nude being particularly sensual and, for the day, shocking.

Alfred Stieglitz, photographed by Carl Van Vechten in 1935 (Library of Congress)

A young woman artist struggling to establish herself will not complain too much if her name is already known, even if for scandalous reasons. O’Keeffe was also immensely talented, as Stieglitz, who gave her her first show, was not the first to see. One imagines that he enjoyed his role of Pygmalion, sculpting, detail by detail, the outlines of his own Galatea. As for O’Keeffe, her letters to him are a mixture of deference, shy confession, and the blurting out of feelings, followed by admissions that she did not know who she was. Of course she was going to marry him—he had the ability to guide her talent and give it plenty of exhibitions, and she needed his support. So, in due course, she did.

The last person in the group, Rebecca Salsbury, arrived when she married Strand in 1922. The daughter of Nate Salsbury, who managed Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show for years, Rebecca, or “Beck,” as she came to be called, combined practical qualities with amused tolerance and was not particularly interested in being famous. While the others worked all the time, she liked nothing better than donning a pair of pants and throwing herself on a horse. She painted a bit and tried photography, but readily took on the role of a secretary, typing up the others’ manuscripts, and provided the light relief.

O’Keeffe began to move away from New York when, in 1929, Salsbury introduced her to Taos and O’Keeffe began spending part of her year in the Southwest. There she launched herself on the series of flower paintings that made her famous. She still joined Stieglitz in New York but, as fate would have it, was not there in 1946 when he suffered a cerebral thrombosis and died. As for Strand, his interests, like those of another teacher, Lewis Hine, moved into documentaries and photographs documenting social change around the world. O’Keeffe lived the longest, until her 98th year. True to form, she spent her later years learning how to make pots under the new tutelage of John Bruce Hamilton, called Juan, a handsome young potter who bore a strange resemblance to Stieglitz.

In later years, despite their travels, the four remained in warm contact. But the many subterranean ways in which they may have influenced each other, professionally and personally, remain elusive. Such things are unlikely to be found in caches of letters in any case, no matter their source, and these letters are no exception, despite the careful attention Burke gives them. In the end, only the people involved could ever really know.