Reborn in the City of Light

At a time when Paris was an incubator of modernism, a group of bold American women arrived to make art out of their lives

In 1935, Berenice Abbott was photographing scenes for her monumental collection Changing New York when a male bureaucrat at the Federal Art Project admonished her. “Nice girls” didn’t venture into rough neighborhoods like New York City’s Skid Row, he said.

“Buddy, I’m not a nice girl,” the 37-year-old Abbott snapped back. “I’m a photographer … I go anywhere.”

Abbott is among an extraordinary array of “not-nice girls” whose work is now on display at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., in an exhibition titled “Brilliant Exiles: American Women in Paris, 1900–1939.” The works suggest the dramatic differences among these expatriate American artists, writers, and performers who found their way to Paris from the turn of the century to the outbreak of World War II. Only some of these women—Black and white, straight and queer, wealthy and barely scraping along—knew one another, and each brought her own story to the city of art. But they had in common a fierce desire for freedom: from sexual repression, from racism, from the stifling social conventions they experienced to varying degrees at home. Abbott herself discovered her gift as a photographer making portraits of her contemporaries in Paris. “We were completely liberated,” she declared years later.

The artists range from African Americans like Loïs Mailou Jones and Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, who were free to exhibit in the Paris Salon but lived in straitened circumstances, to white heiresses like Natalie Barney and Romaine Brooks. The exhibition also shows the importance of formal groups: Barney’s salon on the rue Jacob, with its tucked-away garden and classical “temple of friendship,” attracted a glittering company of artists and intellectuals (not all of them women, though Barney’s writing and publicized love affairs made it clear that she had created a cult site for the celebration of lesbian love). The salon of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas on the rue de Fleurus set a more sober tone, as revealed in Man Ray’s photograph of the two women surrounded by their art collection; that cult was dedicated to the most exacting experiments in modern art: the paintings of Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Henri Matisse, and Juan Gris. “No American writer is taken more seriously than Miss Stein by the Paris modernists,” wrote Janet Flanner, who, under the pen name Genêt, became the recording angel of her peers’ artistic exploits in The New Yorker’s “Letters from Paris” from 1925 to 1975. Sylvia Beach’s visionary bookshop Shakespeare and Company provided yet another refuge where French and American writers could gather, becoming legendary when Beach published James Joyce’s Ulysses in 1922. Stein described the lure of Paris in her story “Miss Furr and Miss Skeene,” based on the artists Ethel Mars and Maud Hunt Squire: “They were in a way both gay there where there were many cultivating something”—one of the earliest uses of gay to suggest homosexuality. Paris gave all these women a space where they could reinvent themselves and “cultivate something.”

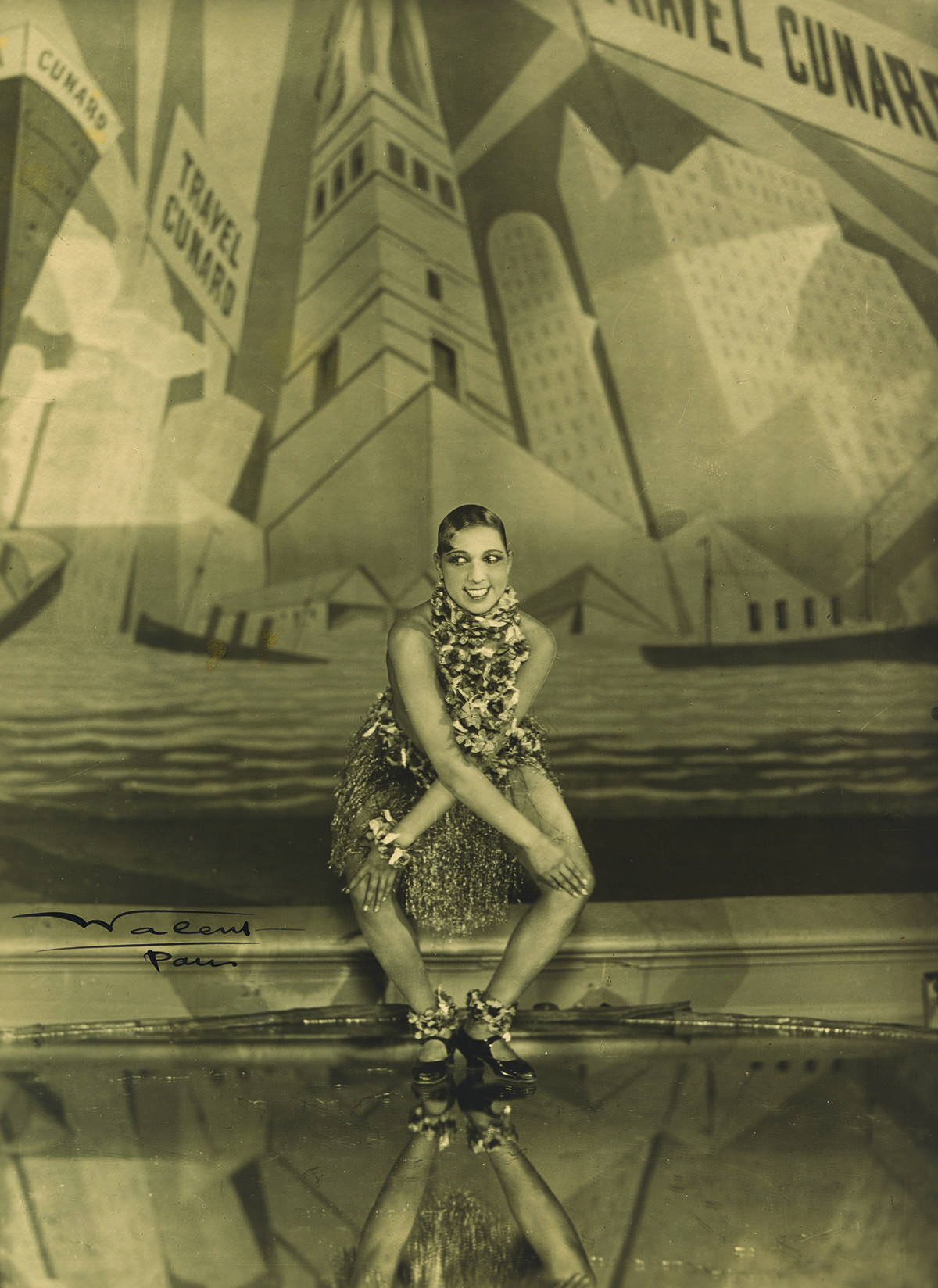

Josephine Baker, 1926. Stanislaw Julian Ignacy Ostroróg, known as Walery (1863–1929). Gelatin silver print, 8 ¾ × 6 ⅜ inches. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

The spectacularly elastic singer and dancer Josephine Baker brought her own electrifying revolution to Paris in 1925, when she was just 19 years old. When Flanner wrote about Baker in one of her first “Letters,” she hardly knew what to make of the performer. In 1972, Flanner did penance for this incomprehension in the introduction to her book Paris Was Yesterday:

[Baker] made her entry entirely nude except for a pink flamingo feather between her limbs; she was being carried upside down and doing the split on the shoulder of a black giant. Midstage he paused, and with his long fingers holding her basket-wise around the waist, swung her in a slow cartwheel to the stage floor, where she stood, like his magnificent discarded burden, in an instant of complete silence. She was an unforgettable female ebony statue. A scream of salutation spread through the theater.

Baker almost steals the exhibition, so striking is her presence in the portrait by Walery, the pochoir lithograph by Paul Colin, the watercolor by José María Escacena, and other lively photographs and posters. In Walery’s picture, she’s dancing the Charleston, crossing her arms over her legs in the “bee’s knees” maneuver, her body’s geometry echoed in the Art Deco backdrop of skyscrapers and ocean liners, her smile a delirious triangle. Baker’s remarkable life story extends beyond the bounds of the exhibition. She danced across Europe, spied for the French Resistance during World War II, addressed the crowd at the March on Washington in 1963, was awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Légion d’honneur, and was inducted into Le Panthéon in a symbolic coffin (her body remains buried in Monaco).

Flanner—Genêt—emerges as another dominant figure in the exhibition. She knew everyone in Paris and picked up all the scuttlebutt, her New Yorker letters documenting 50 years’ worth of the city’s gossip and scandals, politics and cultural goings-on. Like so many of these women, she was a lesbian, first living in Paris with the writer Solita Solano, eventually leading a complicated life with romantic attachments to three women at the same time: Solano, the singer Noel Haskins Murphy, and the Italian broadcaster and editor Natalia Danesi Murray. Flanner’s story, like Baker’s, stretches far beyond this show. She spent World War II in New York writing on European politics, but in November 1944 she returned to Europe and hurtled around the war-ravaged continent reporting on Buchenwald (new corpses were discovered on the day of her arrival), the Nuremberg trials, and the masses of displaced and traumatized people. In 1958, she documented the Algerian crisis that brought France to the brink of civil war.

In the 1920s and ’30s, however, Genêt witnessed frivolity, not atrocity, and her early letters reflect this. Her rhythmic wit still stings. Describing how the demimondaine Liane de Pougy was “launched” at the Folies Bergères by the prince of Wales, Flanner wrote that the courtesan “sent a note saying, ‘Sire: Tonight I make my debut. Deign to appear and applaud me and I am made.’ He did and she was. Shortly after this, men began dying for her. She made suicide fashionable.”

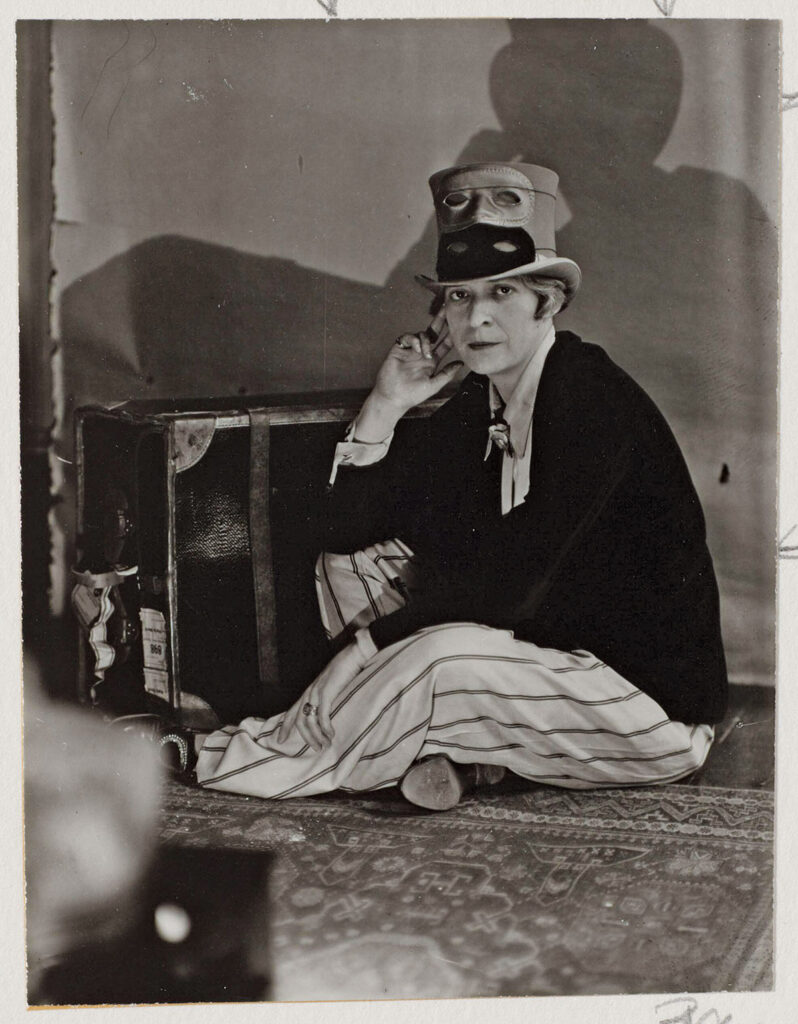

Flanner dressed as stylishly as she wrote. Abbott fixed the iconic image of the writer wearing a top hat decorated with two Mardi Gras masks (the hat belonged to her friend Nancy Cunard’s father). Beneath their empty eye sockets, Flanner stares directly at the camera with an amused look that is somehow both whimsical and serious. She expresses complete and unrepentant self-possession.

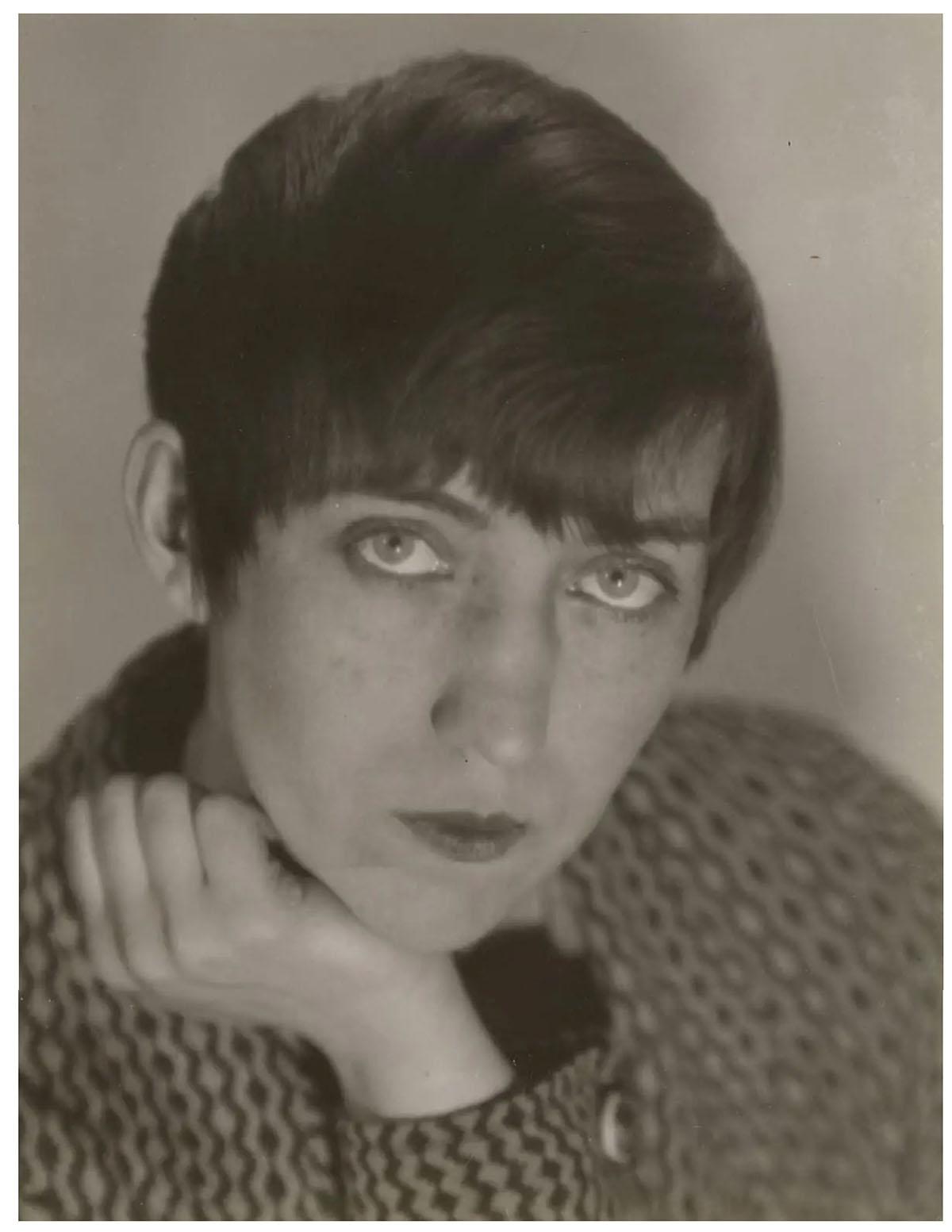

Self-Portrait, c. 1932. Berenice Abbott (1898–1991). Gelatin silver print, 5 9⁄16 × 4 5⁄16 inches. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Abbott watched the expatriate Parisian world as searchingly as Flanner did, and a great deal that we know about it, we know from her pictures. Like Flanner, she came from the Midwest. Her father, like Flanner’s, committed suicide. But where Flanner’s family was shakily middle-class, Abbott’s skidded almost to destitution. Impatient for a more challenging artistic life, she left Ohio State University without a degree, bobbed her hair, and followed friends to Greenwich Village, where she survived on odd jobs, started sculpting, and consorted with the radical intelligentsia. She arrived in Paris in 1921 with almost no money but a mad faith that things would work out. And they did: Man Ray, whom she had known in New York, eventually hired her as a darkroom assistant for his flourishing photography business. She taught herself to take and develop photos and thus discovered her life’s work. She also discovered that she loved women. She began to frequent lesbian bars and had a few brief romances (including one with the American artist Thelma Wood and one with the Russian-Polish model Tylia Perlmutter), though she seems to have reserved her main energies for art, not for love. A cranky, determined visionary, Abbott soon set up her own studio. Her first solo exhibition in Paris, in 1926, presented portraits of contemporaries Djuna Barnes, Jean Cocteau, André Gide, Marie Laurencin, and James Joyce, pictures that have become classics. One reviewer called her “the best portrait photographer in Paris, which is to say, in the world.”

In her self-portrait, Abbott gazes at us with mesmerizing eyes. The more I gaze back, the more radically seen I feel, as if she were reading my soul. She’s a snake charmer. Her sitters must have felt this way. “We cannot go on just looking at things on the surface—we must go deeper,” she said in a 1939 interview. With her pale, oval face, her dark bangs, her chin resting on her hand, she looks like a waif or a pixie. She had no family support, nothing to fall back on. She lived for and in her art. She was a purist, the seer par excellence of her era.

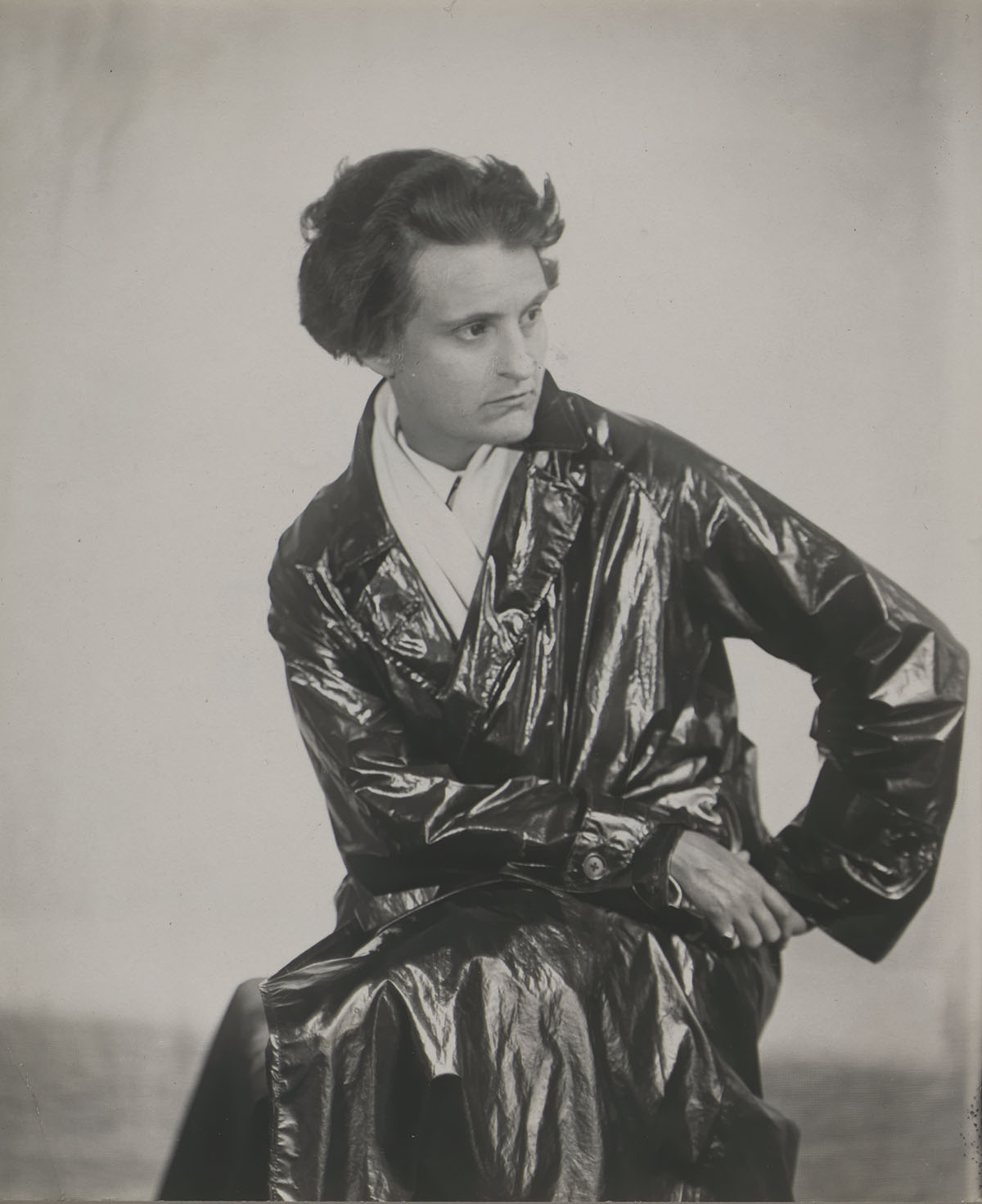

Sylvia Beach, 1928. Berenice Abbott (1898–1991). Gelatin silver print, 3 ¾ × 3 ⅛ inches. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

One of the people she saw was Beach, whose bookstore became a sanctuary for Abbott, too shy and poor to hobnob with Natalie Barney’s crowd or to frequent the Stein and Toklas salon. Brought up partly in Paris because her father had served as associate pastor of the American Church there, Beach returned to Europe during World War I to work for the Red Cross. Inspired by her friend (and future lover) Adrienne Monnier, who ran the French bookstore La Maison des Amis des Livres, Beach opened her own store in November 1919, just as the armistice was signed. Beach, too, was a seer: she intuited which books would matter, supported authors financially, hosted readings in English and French. Shakespeare and Company became the Grand Central Terminal of international modernist writing.

Abbott’s photo captures Beach in an unusual pose and garb. With her dark hair cropped short and brushed back, a little wildly, from her wide forehead and firmly modeled face, Beach is seated, twisting to the left with her left elbow stuck out. She’s wearing a dramatic shiny black leather coat and a white scarf. She glistens with intellectual intensity. The woman who helped bring Ulysses into the world has no time for nonsense.

Spanning four decades, “Brilliant Exiles” charts rapidly changing conventions in art. Ethel Mars, one of the earliest of the “exiles,” arrived in Paris with her lifelong companion, Maud Hunt Squire, in late 1905 or early 1906. They were both professional illustrators who had been supporting themselves in New York. In Mars’s Woman with a Monkey, which she showed at the Paris Salon in 1908, she handles the postimpressionist idiom with aplomb. Probably a self-portrait, the painting presents a fashionably dressed young woman, seated, wearing an elaborate hat—a sculpture in and of itself, a dead bird hanging off one side. Mars toys with convention in this portrait as she did in life. The lady has a magazine-pretty face with symmetrical features and a pert nose. She holds a fan in her graceful hand, a nod to the popular Japonisme of the period and to Mars’s interest in Japanese prints. But the lady’s dark eyes smolder, she slightly bares her teeth, and both the bird on her hat and the monkey perched on a shelf just above her suggest an animal energy quite at odds with the sitter’s demure femininity. Mars, depicted in Stein’s story as “Miss Furr” (another animal touch), was both “regular” and “gay,” the two sly, playful words on which Stein built her portrait of Mars and Squire: “They did then learn many ways to be gay and they were then being gay being quite regular in being gay.” In her typically oblique way, Stein challenges her readers to think about conformity and nonconformity in queer life.

Woman with a Monkey, 1908. Ethel Mars (1876–1959),.Oil on canvas, 42 ½ × 31 ½ inches. Springfield Art Association of Edwards Place.

By the time Loïs Mailou Jones arrived in Paris in 1937, to study at the Académie Julian at the age of 32, modern painting had gone through the convulsions of Cubism and the postwar return to diverse forms of figuration. Jones had trained at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and the Designer’s Art School in Boston, and she had been teaching at Howard University. But she had been consistently hampered by racism and discrimination, finding limited opportunities to teach and exhibit her work outside historically Black colleges. In Paris, she said, she felt “shackle-free.” She painted with fervent energy; she became friends with French painters, especially Céline Tabary, with whom she shared expeditions in painting for years to come; her work was shown at the Société des Artistes Français and praised in the press. Her self-portrait, made on her return to Howard in 1940, is a far cry from Mars’s lady of 1908. Whereas Mars’s image declares elegance, sophistication, and a shade of fin-de-siècle naughtiness, Jones depicts force and determination. She has caught the spirit of Cézanne, simplifying planes and bending perspective. This woman stands boldly at her easel, her broad, powerful face glinting in bronze. Her cadmium-red blouse and loose blue jacket hold the foreground, and she grips a bunch of brushes in her right hand as if they were weapons. Behind her hangs a replica of her celebrated still life Les pommes vertes, which critics had admired in Paris, and in the lower left corner stand two African statuettes, the kind she had studied at the Musée de l’Homme. She holds her own. She has synthesized the style of the École de Paris with her African heritage and made a strikingly unified statement.

Jones’s work is preserved in major collections, including the Metropolitan Museum and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The sculpture of Nancy Elizabeth Prophet—who had Narragansett-Pequot as well as African-American ancestry—met a different fate. It is a tragedy that so little of it survives, since in her late years she was too poor to store it properly. She spent 12 years in Paris, arriving in 1922. She had graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design, training she paid for by working as a maid. In Paris, where many artists were poor, her poverty also stood out; she often didn’t have enough to eat, and she was frequently sick. She seems to have been an obsessed solitary, utterly committed to her art. Not completely alone, however; she corresponded with W. E. B. DuBois, who clearly admired her, and other artists in Paris were aware of her, though perhaps wary of approaching her.

Self-Portrait, 1940. Loïs Mailou Jones (1905–1998). Casein on board, 17 ½ × 14 ½ inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Bequest of the artist.

The two carved wood heads by Prophet in the catalog (though not in the exhibition) are works of majestic discipline. They can stand next to anything by Constantin Brâncuși. Both the narrow, androgynous Untitled (Head ) and Congolais, the head of a Maasai warrior suggesting Prophet’s mixture of Central and East African styles, achieve a radical simplification of form while at the same time honoring an essential realism. In this delicate balance they resemble ancient Egyptian sculpture. In the exhibition, the mysterious sculptor is more present in images of her, rather than by her; a photograph from 1924 shows her in profile, wearing a loose patterned blouse and a string of beads, head slightly bowed as if in reverence to art. In another, she’s dramatically costumed in a pilgrim hat, high-collared coat, and the same heavy beads. Prophet’s work did win recognition in Paris; she exhibited regularly at the Salon d’automne and in 1929 at the Paris Salon, where a critic called her “one of the most expressive sculptors of her country and her time.”

Natalie with Violin, date unknown. Alice Pike Barney (1857–1931). Oil on canvas, 78 ⅜ × 44 ⅛ inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of Laura Dreyfus Barney and Natalie Clifford Barney in memory of their mother, Alice Pike Barney.

It wrenches the mind to turn from Prophet’s severe concentration to the extravagance of Natalie Barney’s salon. Bilingual, partly brought up in France, Barney created her dazzling center honoring lesbian love using the fortune she had inherited. It would have been impossible to launch a mission on this scale in the puritanical United States. Barney’s physical beauty was also extravagant, as was her erotic appetite: her long string of love affairs with famous and titled women makes for exhausting reading. Barney’s mother, the painter Alice Pike Barney, depicted her daughter in an astonishing manner—a full-length portrait exuding sensuality. The young woman sits enthroned, her famous Venetian gold tresses flowing over her shoulders and an almost papal, floor-length red velvet robe revealing, in radical décolleté, a Rubenesque bust. This model is not a sex object but a sex subject, fully aware of her powers. Her large, heavily lidded eyes look invitingly sleepy, her full lips invitingly soft. Perhaps Maman was imagining Natalie as Sappho, or a muse: she holds a violin in her right hand and a musical score on her lap.

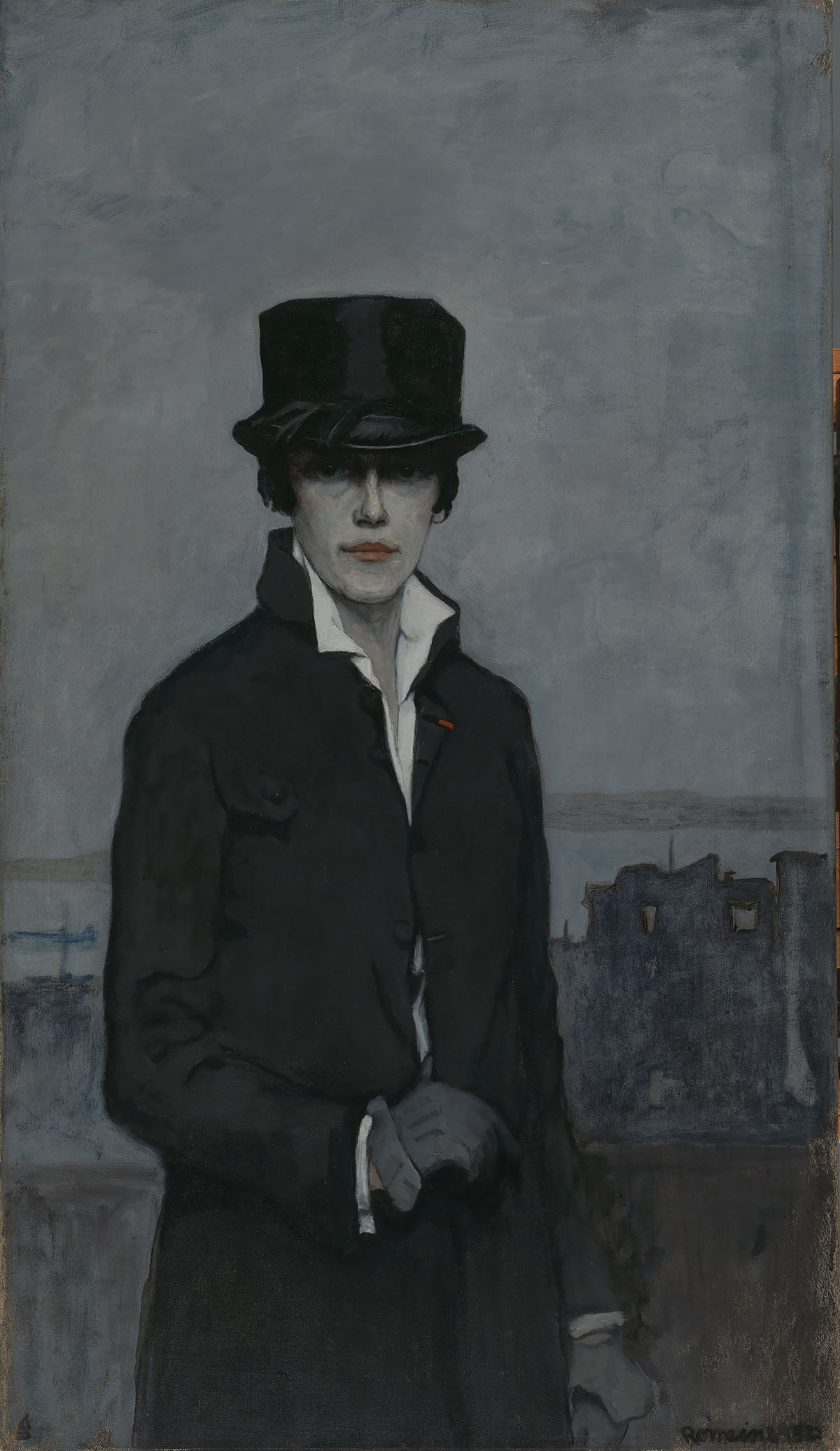

The younger Barney wrote and published a number of books, mainly collections of poetry in English (and sometimes in French), verse of stultifying preciosity. “Ethereal vibrations / And soulful pulsations / Of song …” reads the poem entitled “Singing.” But her true works of art were herself and her salon. It’s a different story with the painter Romaine Brooks, Barney’s romantic partner of 50 years (along with her other “steady,” the Duchesse Élisabeth de Gramont). Abandoned by her parents and raised in poverty, Brooks inherited a fortune after her mother’s death in 1902. She knew early on that she was attracted to women and that she would be a serious artist. She established herself in Paris in the early years of the century, painting fashionable portraits that created a stir at her first solo show, at the Durand-Ruel gallery in 1910. She adopted impeccable gentlemanly dress, as seen in her self-portrait from 1923. She’s the artist as dandy—slender, vertical, wearing a tightly fitted dark suit with the red ribbon of the Légion d’honneur in the lapel, and a dark, androgynous hat that shadows her eyes. She has a long, narrow face; only her red lips suggest a feminine touch. Her hands are protected by gray gloves. The whole painting is keyed to tones of gray; she stands against a claustrophobic sky and a ghostly seaport.

Self-Portrait, 1923. Romaine Brooks (1874–1970). Oil on canvas, 46 ¼ × 26 ⅞ inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of the artist.

The American women who reimagined their lives in Paris from 1900 to 1939 were fortunate in their timing. They came just as Paris was incubating modern art for the world. As foreigners, they weren’t subject to the conventions of French bourgeois society, while escaping similar constraints at home. Some of them experienced the shock of the Great War, more or less indirectly, but they nearly all took part in the heyday of Les Années folles that followed. They not only made themselves, they also helped make modern culture.

“Brilliant Exiles” concludes with a second great shock, Hitler’s invasion of Poland and the outbreak of World War II. Civilization takes centuries, and immense effort, to create. As we keep learning, over and over, it can be destroyed in the blink of an eye. This is the note in Janet Flanner’s letter from September 3, 1939. She called the war that had just been declared “a commonplace war” (little did she know!) but, she concluded, it “is only because of its potential size that it may, alas, prove to be civilization’s ruin.” Civilization, albeit forever changed, survived that war, as this radiant, defiant exhibition proves. Yet the show also warns us to cherish the freedoms that peace allows, and never to take peace for granted.