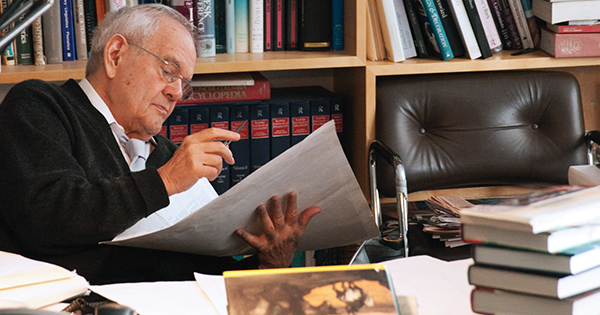

Remembering Bob Silvers

The legendary New York Review of Books editor knew everybody, had read everything, and oversaw every stage of what he published

Half the fun (at least) of being an editor of a literary review must be matching a book and its reviewer. What will that reveal about the book, and what about the reviewer, and what about their conjunction? Robert B. Silvers, who with Barbara Epstein (his co-editor for 43 years until her death in 2006) had that duopoly followed by his monopoly for all the life of the “paper,” as they called The New York Review of Books. Silvers, who died in March, wanted to get something new out of each matchup—his favorite term of praise for the result was that it said something “fresh.” But he did not think of the job as confined to just that one creative gamble. He personally oversaw every stage of the resulting review, suggesting further insights, sending ancillary books or articles, negotiating phraseology. One often got the feeling that this was a man who had met everybody and read everything. Yet how could he do that, chained as he was for most of every day, weekends and holidays included, to his editing desk?

Of course, he did not do it alone, or just with Barbara. He had an incredibly skilled staff—usually three principal assistants—in the office with him, across from his desk, getting the appropriate references, linking Bob by phone with the author when Bob or the reviewer was traveling, checking references. I learned how these anonymous workers were chosen when a very promising student of mine, about to graduate from Northwestern University, applied to be one of Bob’s assistants. Bob called me about the young man and asked the expected questions. Did he have wide interests, cultural and political? Had he more languages than English? Did he write well? I assured him he was well qualified on all those counts. And then he asked me an unexpected question: “Does he have a sense of humor?”

I told him I had not been given an occasion to observe that. With a disappointed air, he said, “No one can survive around here without a sense of humor.” I realized from that conversation what pressure these young talents were under to perform. But whenever I observed Bob and Barbara together, in the office, at a restaurant, or at the opera, I could tell that a perpetual chuckling at the odd world around them had to be life-sustaining under a crushing workload. My student was not hired; but I don’t know if that could be ascribed to his not evidencing a sense of humor. Bob had other tests when interviewing for the post—including a written analysis of an author or a piece in the Review.

I know of former assistants who certainly do have a sense of humor—especially Jon-Jon Goulian, the New York eccentric who worked as an assistant organizing Bob’s library. Others, after time in that pressure cooker, have become well known in the literary, academic, or film worlds—Nathaniel Rich, A. O. Scott, Mark Danner, Jean Strouse, Deborah Eisenberg. Everybody in the New York literary world knows about these fabled assistants. A tenure of two years or so gave them a prized résumé. They had been at the center of literary and intellectual traffic of the highest kind. They had watched Bob coax reviews from sometimes resisting authors. They had seen the great tact with which Bob suggested a change in copy. They had watched as publicists came with their seasonal book catalogs and tried to convince Bob or Barbara that some of their upcoming titles would be right for the Review. (The publicists had better know what the Review had already published on this subject or by that author.)

Bob’s customary way of soliciting a review was not to write or call with a request but to send a book (or a set of them) out of the blue with his handwritten note asking whether the writer could say something about this. Length and due date might be mentioned if Bob thought acceptance was probable, but he could be cagey about that if more negotiation was required. I was often surprised by the book(s) that came by courier (once to me in Rome). When Bob sent me Marilynne Robinson’s 2015 book of essays, The Givenness of Things, I told him on the phone that I had never read a book of hers—I just knew what President Obama had quoted from her in his eulogy for the murdered pastor and members of Mother Emanuel Church in Charleston. Bob was sure I would be the person to savor her if I just dipped into the book—and he was right. I read all of her novels to write what I thought worthy of her.

I could not tell whether he would assign a book to me if I requested it. Sometimes he had already assigned it (or he might have thought I could not do it as well as someone else he was considering). But if I was near an event of some interest, if I was in Italy where a major exhibit was being mounted—on Frederick II at the Palazzo Venezia in Rome, on Pope Sixtus V at the Scuderie del Quirinale, on Renaissance architectural models in the Palazzo Grassi in Venice, on a Pordenone exhibit in Empoli, on Tintoretto’s portraits in a converted church in Venice—he was glad to hear what I had to say about it. I told Bob the Tintoretto show would not open until three days after my wife and I had to leave Venice. He faxed the famous curator of the show with a request that she give me a private tour before the opening, and she did. Bob’s writ ran far.

Some of his commissions I would never have expected. He sent me to Minnesota to interview Gov. Jesse Ventura. (Ventura was a kind of proto-Trump, though we did not know it at the time.) Other assignments were more natural. Bob seemed to remember everything he had run in the Review. Many years before, I had quoted John Ruskin in a review of an unrelated book; recalling that, in 2014 he sent me to an exhibit of Ruskin’s delicate scientific watercolors in Toronto. Other ideas followed on his own favored subjects. He had a fondness for Chicago, where in 1947 he had graduated from the University of Chicago at the precocious age of 17. The university was still fizzy at the close of Robert Maynard Hutchins’s presidency. When I moved there, Bob started sending me books on the city—its history, its architecture, its theater. After I had reviewed a few of these books, he suggested I do more and turn them into a book on the city for the fledgling New York Review Press. I had to confess I was all Chicagoed-out. The same thing happened when I did some reviews on Catholic subjects. When he sent me another one, I told him I was all poped-out. (Francis would later reawaken that interest.)

Bob was in many ways traditional. He kept up with developments, but with a sense of their strangeness. In 2010, he called and asked me if I would write regularly for a blog the Review was starting. I told him I did not even know what a blog was. He chuckled his regular chuckle and said, “Neither do I. But I’m told it will be good for the paper.” And so it has been. Edited by Hugh Eakin along the same lines as the major venue, it has given writers the opportunity to respond to developments in a daily (not a biweekly) posting. It is now appropriately called NYR Daily.

Some people feared that Bob had not prepared a successor for the Review—but the blog is there ready to keep up the same standards. The proud connection of writers with what he has created will not simply disappear. I am sure all its writers felt as privileged as I have to appear on the same pages with heroes of mine—Murray Kempton, Joseph Kerman, Joan Didion, Elizabeth Hardwick, Edmund Morgan, and all the many others. That kind of company does not simply disappear. Bob built it to last.