The Dawning Moon of the Mind: Unlocking the Pyramid Texts by Susan Brind Morrow; Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 291 pp. $28

Once during a class with the renowned classicist Wendell Clausen at Harvard, I exclaimed about Greek and Latin poetry’s hexameter lines (the basis of which is a long beat and two short ones, as in a classic western’s credit music), “Listen, it’s a horse galloping—” The professor cut me off. Imaginative but impossible, he said: epic verse predated the introduction of the domesticated horse to Europe. Yeah, well, that didn’t make my observation moot, since the Eurasians, who domesticated the horse on the steppes as early as 4000 B.C., brought both it and many elements of epic poetry to Europe proper around 2000 B.C.; galloping horses might well have been behind the hexameter.

But I didn’t know that at the time—and I didn’t think to check the facts on my own. I only shut up in shame and for years accepted my flaky failure and even felt the need to treat poetic, “feminine” observations as inapplicable to anything technical that I learned. This is why I have to admire Susan Brind Morrow, a scholar in Egyptology—a linguistic field many times more difficult than Classics. She apparently never took no for an answer concerning her own feeling and reasoning capacity or the breadth of context that might be worth considering.

Morrow, who began her study of hieroglyphs at Columbia at age 16, is an accomplished poet. Moreover, she not only joined archaeological expeditions in Egypt but also familiarized herself with the local culture and knows a great deal about the landscape and natural history. This background allows her to speculate convincingly about the meanings of particular shapes in the hieroglyphs, from those associated with characteristic implements to those representing indigenous birds. She also learned Egyptian Arabic, with its parallels in grammar and phonology to its remote ancestor.

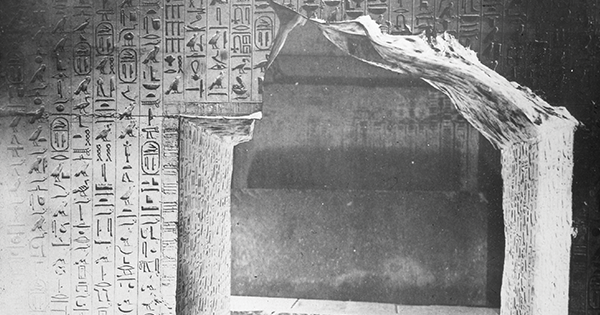

She is thus superbly qualified to give a both literary and practical account of the first extant “pyramid texts”—hieroglyphs inscribed on the interior of a tomb to aid or describe the dead person’s journey to the next world. Her new book explicates and translates the hieroglyphs in the pyramid of Unis, a pharaoh of the Fifth Dynasty who reigned around the middle of the 24th century B.C. Morrow negotiates between pictogram and phonetic marker, sorting out images, ideas, and sounds, as well as their linkages in puns and riddles, to come up with a set of meanings that, centrally, connect the astronomy around the annual flooding of the Nile to the posthumous ascent of life.

In her prologue, she gives a good tutorial on how hieroglyphs are physically arranged, some basic signifiers, and some handy tricks for reading. The tutorial is meant for the uninitiated reader, and I could follow it even though my only Semitic language is classical Hebrew, which has a sharply different writing system.

The major hiccups in the book are in the relationships among the otherwise wildly discursive prologue; the translation itself, which makes up the central portion of the book; the separate extensive commentary on individual verses; and the short but important section, “Egyptology: Settling a Dispute.” I would rather have read this last section first because it is clearest here why the translation is both necessary and well grounded. I also wish the commentary had been better integrated into the translation, either as introductory or concluding accounts of the text in the different parts of the tomb, or as footnotes.

This integration would not only have saved much flipping back and forth but might have—through constant reminders not to compete with the beautiful text itself—helped discourage the translator from attempting long explanations often reminiscent of New Age spirituality. For “Ma’at, the embodiment of truth, marked with a feather,” for example, a short account (or better, two or three alternative ones) of the image’s function would be plenty. This note should not have extended to more than a hundred words, concluding with, “The wind is the witness, even as the death rattle itself, the expiring of the person through the mouth, the voice of the truth of the life energy leaving the body.”

As especially evident in the prologue, Morrow takes the “feminine,” personally interpretive strain too far, embraces ancient Egyptian literature too tightly, and infuses it with romantic nostalgia—and this is the ultimate wrong field in which to do these things. Hieroglyphs are so hard because they were part of extravagant, sealed, secret offerings to autocrats who claimed an exclusive afterlife. For the hieroglyphs’ patrons, the intimate interest in the natural world had to do, self-evidently, with mastering that world and the populations dependent on it. (If you could exactly predict the annual Nile flood, for instance, you could more easily withhold and distribute water.) And this power was so great that it wasn’t supposed to end along with life.

The now-prevailing teachings to which god-kingship gave way, our real and solid intellectual and cultural life, insist on the opposite: death, as construed both inside and outside religion, does not prolong and heighten the privileges of material power but is a just equalizer. An acknowledgment of this immense difference (for one) must temper any defensible presentation of hieroglyphic poetry; Morrow’s presentation reminds me, instead, of fantasist views of the “spiritual,” “nature-loving” Druids (another elite, hermetic, almost self-erasing cult), the purported originators of all that is enlightened in ourselves.

The prologue and the Egyptology sections contain the most striking contrasts of the book’s virtues and excesses. Of course it was stupid for anyone in a past generation of scholars to see in the tomb’s baboon imagery not the Egyptian baboon, an integral and revered part of the natural world and hence of thinking about the afterlife, but our screeching, obscene pest. Still, the care she takes to see Egyptian thought in its context, to give it the benefit of the doubt, should not have been pushed into overidentification. T. S. Eliot, Whitman, Emerson, and St. Augustine don’t elucidate anything here. Neither do statements like “Plotinus and his Neoplatonism are found at the heart of Jewish and Christian and Islamic mysticism. This heart, his thinking, is the religious sensibility of Egypt.”

But it is not the explicit justification of a translation but the translation itself that has to persuade. Does it plausibly cohere? Would it arguably have appealed to the original writer’s peers? Is this what somebody of that time and place would have written? (Thucydides’s prescription for unknown and unknowable speeches: what people are likely to have said.) Morrow’s English version of the hieroglyphs does pass muster. Here is one of my favorite passages:

The horns of your life force come out upon you

The horns of your father come out upon you …

Go with your light. You are pure.

Your bones are the bones of little falcons

Of holy serpents in the sky.

You exist at the side of the holy.

Leave your house, all that concerns you, to your son.

You of the name of Unis are called to rise.

The earth has ordered him onto the path of the turning sky,

Where he has placed him.

You are pure as the stars are pure.

O you in bonds, break free.

On the shoulders of a falcon, in his name,

Inside your vehicle of light,

For you are one of the beings of light.

You are raised up among the indestructible stars,

The ancient ones, for you are from the place below,

As your father was from the place below, the earth.

Better than an unassailable reconstruction of the original—and how could that exist anyway?—Morrow’s translation is a new and exciting piece of literature.