Safer Than Childbirth

Abortion in the 19th century was widely accepted as a means of avoiding the risks of pregnancy

Listen to our interview with Tamara Dean about this essay on Smarty Pants.

At our rural county’s historical society, the past lives loosely in bulletins, news clippings, plat books, and handwritten index cards. It’s pieced together by pale, gray-haired women who sit at oak tables and pore over old photos. Western sun filters in, half-lighting the women as they name who’s pictured, who has passed on. Other volunteers gossip and cut obituaries from local newspapers.

I was sent here by hearsay. For years, my neighbor has claimed that the old cemetery in the low-lying field on my Wisconsin property contains more bodies than the scant number of tombstones indicates. The epic flood of 1978 washed away the markers of the nameless—Civil War soldiers, he says. I want to know who the dead were in life. After many walks through the cemetery, I’m familiar with the markers that remain. One narrow footstone reads simply, “MAS.” Three marble headstones rest at odd angles among the box elder trees. Stained, eroded, and lichen crusted, the stones belong to a boy and two baby girls who died in the 1850s and ’60s. On the boy’s is a relief of a weeping willow; on the sisters’ are rosebuds. Signs of young lives cut short.

I’m sitting at one of the oak tables when Carol, the historical society’s assistant curator, hands me a binder of cemetery records. A stranger has just sat beside me, her husband opposite us. I study the list of those buried on my land. I recognize the children’s names. I don’t see any men’s names. But there’s the name of a woman I’ve never heard of. I read it aloud: “Nancy Ann Harris.”

The stranger says, “She was married to Benjamin Franklin Harris, who’s my husband’s great-great-great uncle.” She nods to her husband, who nods in confirmation.

Astonished, I turn to face her. “How do you know that?”

“She died of an abortion,” the stranger adds. “Apparently, she’d had a lot of them.”

“How do you know that? ”

“Her death record.”

“Why would they put that in the public record?”

Carol, standing nearby, says, “It was a different time.”

I want to ask her what she means, but another woman, who has been eavesdropping, leans toward me and frowns. “That Nancy must have been something else,” she says.

I’m startled by her dismissive tone, her vague implication. I don’t think quickly enough to challenge her. Instead, the rest of us—Carol and I and the stranger and her husband, whose great-great-great aunt lies in my field—turn silent. I look down again at the five names of the buried. Long after I leave the table, I keep wishing I’d spoken up.

On my land in rural Wisconsin, the past exerts itself. It affects me. I slop through the channels left by long-dead farmers. I eat apples from trees planted by settlers and groundnuts cultivated by Native Americans. I laze in the shade of oaks left unlogged for that purpose and let a field that was burned intentionally for centuries burn its way back into prairie again. I’ve wondered about those who plowed, planted trees, and set fires. Now Nancy reaches forward and casts me to conjure her.

The life of her husband, Benjamin Franklin “Frank” Harris, is well documented. He was a Civil War soldier who belonged to a famous brigade. But my research yields no clues about Nancy’s origins or biography.

On another visit to the historical society, I ask Carol, “Do you have any files about abortion in history? Or women’s reproductive health in the 1800s?” No and no. In our rural county, women’s history is depicted in sepia-toned images of farm wives, teacher-training school graduates, and early suffragists. Private pains and joys remain private, lost to us.

Across town, I stop at the office of the Register of Deeds to see Nancy’s death record. The registrar, a cheerful, talkative woman, shows me just-snapped photos of her granddaughter on her smartphone. She asks me to sign in and state my purpose before she’ll allow me into the records room.

I hesitate.

“Genealogical research?” she prompts.

“Yes,” I say. Let Nancy Ann Harris be family to me.

Nancy’s death on December 16, 1876, at age 35, is among the first to be recorded in the yellowed, leather-bound volumes. The cause, “puerperal peritonitis,” is annotated by a triple-dagger symbol that directs the reader to a line of script rising up the margin like a pointed finger: “Disease caused by abortion at 3 months this was perhaps the 10th abortion all except this followed by smart hemorrhagae.” It’s the longest description of a death in all of those volumes. Maybe Dr. R. H. Delap, who signed her death certificate, instructed the county clerk to copy his notes without omission. Or maybe the clerk felt he couldn’t abbreviate the doctor’s notes in this case. Only one other record mentions abortion.

But on every page of those early volumes, women aged 19 to 47 are listed as dying from puerperal peritonitis, puerperal fever, puerperal septicemia, “inflammation after confinement,” eclampsia, and “giving birth to a child.” I find more dead fertile women than old men.

In Nancy’s time, abortion was a common means of birth control, a way for women of every race and social class to limit family size, manage resources, and protect their health. The procedure was often a safer alternative to childbirth, which some women considered “pathological and frightening” and many others approached with foreboding, according to James Mohr’s 1978 book, Abortion in America. Every woman, including Nancy, would have known friends, sisters, or cousins who died or were debilitated while giving birth. They would have known those who took pains to avoid it.

In the 1700s and early 1800s, conception was considered a disturbance of a woman’s natural balance. Methods of “removing a blockage” or “restoring the menses” were sometimes necessary to reestablish the body’s balance, even if they induced a miscarriage. Abortions that occurred before quickening, which was understood as the time when a pregnant woman could feel the fetus move (usually around the fourth month), were both legally and morally acceptable. Quickening was an indicator based on women’s perceptions, not a medical diagnosis. But in the absence of a scientific pregnancy test, it was recognized as the threshold of human development. Before quickening, no one, not even the Catholic Church, believed that a human life existed, notes Leslie J. Reagan in her 1996 book, When Abortion Was a Crime, reissued earlier this year.

Abortion was so frequent, according to one doctor, that “it [was] rare to find a married woman who passes through the childbearing period, who has not had one or more.” Women spoke of it casually. They might decide to be “put straight,” “opened up,” or “fixed.” (They wouldn’t have said “abortion,” as that term belonged to the medical lexicon, not the vocabularies of ordinary people.) One physician reported that women “talk about such matters commonly and impart information unsparingly.” Although some doctors would perform the procedure, many women, especially in rural areas, induced abortions on their own using drugs or herbs and wisdom passed from one generation to another.

When Nancy was younger, she might have said to a favorite aunt or even Amanda Martin, who had already buried two daughters in my field, “I’ve missed twice and need to bring my course on.” The older women would have understood. After all, they had probably done the same. A 19th-century euphemism for missing a menstrual period was “taking the cold,” implying that pregnancy was a common ailment that came and went. Once asked, they would have helped Nancy.

Years later, she might have felt confident in “removing female irregularity” on her own. I picture her lanky, dark-haired, with deep-set eyes, my portrait patterned after photos of settlers who lived on tracts around mine and whose descendants are my neighbors. I picture her wise. Strong willed. If she found an hour’s respite from chores at her cabin less than a mile from my place, where a tavern now stands, she might have asked her older stepdaughters to take care of her three younger children. She might have left the cabin, walked north over marshy ground, and found what she needed in the hills behind my place: juniper, bloodroot, mayapple, Queen Anne’s lace seeds (in large quantities, taken early enough), or black cohosh, a plant Native American women relied on.

It’s also possible that Nancy sent away for a cure. In the 19th century, abortion became commercialized. Ingredients from herbal folk remedies (aloe, cotton root, tansy, black hellebore, ergot of rye, pennyroyal, motherwort, slippery elm, rue) were made into pills or tonics, which were mass-produced and advertised widely in popular newspapers and magazines. Women could buy them through the mail or from local druggists. Even in rural Wisconsin, Nancy would have seen them advertised. By 1840, sales of abortifacients had surged, and profiteers who publicly promoted services to induce miscarriages flourished. One doctor called it “a regularly-established moneymaking trade.”

Experienced women were savvy about controlling their reproduction. They had advocated for women’s education, made themselves literate, and sought out materials that described feminine organs and ailments, however sketchy that information sometimes was. It’s possible that Nancy tucked The Married Woman’s Private Medical Companion, published in 1847, under a tablecloth in the hutch. She might have noted the causes of abortion listed in the still-popular 18th-century text Domestic Medicine, or, a Treatise on the Prevention and Cure of Diseases, by Regimen and Simple Medicines, such as violent exercise, raising great weights, jumping from a great height, punching her belly, or bloodletting. Maybe, fearful and determined in her first attempt, she opted for violent exercise—perhaps sprinting up the same road I jog down—before trying something else.

According to Reagan, one woman in 1918, after her menses were restored, said to her nurse, “Thank the Lord, I have been relieved.” This is how I envision Nancy on the day after each of her 10 or so abortions—relieved, if tired, and hopeful about her future. Maybe she took a day to rest in bed, asked her son to stoke the fire and one of her stepdaughters to make supper. She might have initially held off her husband, Frank, but then drew him closer, confident that she could deal with any consequences.

Just when Nancy entered married life and was bearing children or choosing not to, the nation’s policies on abortion were changing. Mail-order pills and tinctures were unregulated and sometimes lethal. In the 1820s and ’30s, the risk of poisoning led to the first laws affecting abortion, which penalized those who supplied abortifacients rather than the women who purchased or used them, as long as the women did so before quickening. These restrictions didn’t stop women like Nancy from gathering herbs or sharing home remedies, nor did they eliminate quickening as a legal marker of a viable life.

Punishment for terminating a pregnancy at any stage would come only decades later. In 1857, the recently established American Medical Association (AMA) initiated a campaign, led by Dr. Horatio R. Storer, to end abortion. The organization’s reasons were many, but women’s health was not chief among them. Reagan writes that the AMA and its members were attempting to “win professional power, control medical practice, and restrict their competitors, particularly Homeopaths and midwives.”

Class, racial, and gender anxieties factored into the doctors’ fear of losing power. As immigrants poured into the United States, the birthrate for white, Protestant, middle-class married women plummeted to historic lows that couldn’t be attributed to miscarriage, celibacy, or barrenness. Improved contraception was part of the reason, but so was an increase in the abortion rate. Storer and his peers became preoccupied with the latter—and for reasons that had less to do with protecting the right to life than with maintaining the prevailing social hierarchy. As Reagan writes, “Antiabortion activists pointed out that immigrant families, many of them Catholic, were larger and would soon outpopulate native-born white Yankees and threaten their political power.”

At the close of the Civil War, as the nation was tallying its dead and claiming more land for European-American settlement, Storer wrote a book called Why Not? to persuade white, middle-class women to choose childbearing over abortion. He asked whether the regions west and south of New England should be “filled by our own children or by those of aliens?” He admonished his female readers that “upon their loins depends the future destiny of the nation.”

At the same time, Storer and his male colleagues were heralding medical professionalism, a quality that they felt set them apart from quacks. The AMA anointed men (and only men) who had medical education and practiced orthodox medicine as “regular” doctors, as opposed to “irregular” homeopaths and midwives. (The organization didn’t admit its first female physician until 1876, the year Nancy died.) Regular doctors took the Hippocratic Oath and vowed not to induce miscarriages. In the 1870s, when Nancy was dying of an abortion at three months, AMA-affiliated physicians, who often doubled as politicians, were zealously promoting and pushing new antiabortion legislation.

It’s likely that the doctor who signed Nancy’s death certificate considered himself a regular. Delap had taken medical courses and, for a time, led his county’s chapter of the Wisconsin Medical Society. Like many regular doctors, he also served in the state legislature. Maybe, along with his peers, he lamented how common abortion was. How churches and the press refused to take a stand against it despite being pressured to do so. How women’s education and increasingly public information about abortion had caused a sharp decline in the nation’s birthrate. And how women of his station weren’t reproducing as quickly as immigrant Catholic women.

“Where one living child is born into the world,” states an 1879 report by the Wisconsin Medical Society, “two are done away with by means of criminal abortion.” This was probably an exaggeration. Surveys from around the nation suggested that about one-third of pregnancies during this period were terminated intentionally. But if women kept it to themselves, who knew for sure? After all, abortion was a way to limit fertility privately. It was, writes Mohr in Abortion in America, “a uniquely female practice, which men could neither control nor prevent.” Some men called it “aggressively self-indulgent.”

As women sought to advance their status, regular doctors and politicians attacked abortion as “immoral, unwomanly, and unpatriotic,” writes Reagan. They typically refused to provide information about it or other birth control methods. For regular physicians and legislators, denying women’s rights to continue practicing reproductive autonomy was an existential battle. If they couldn’t control white, Protestant, middle-class women, they would be outnumbered in the New World.

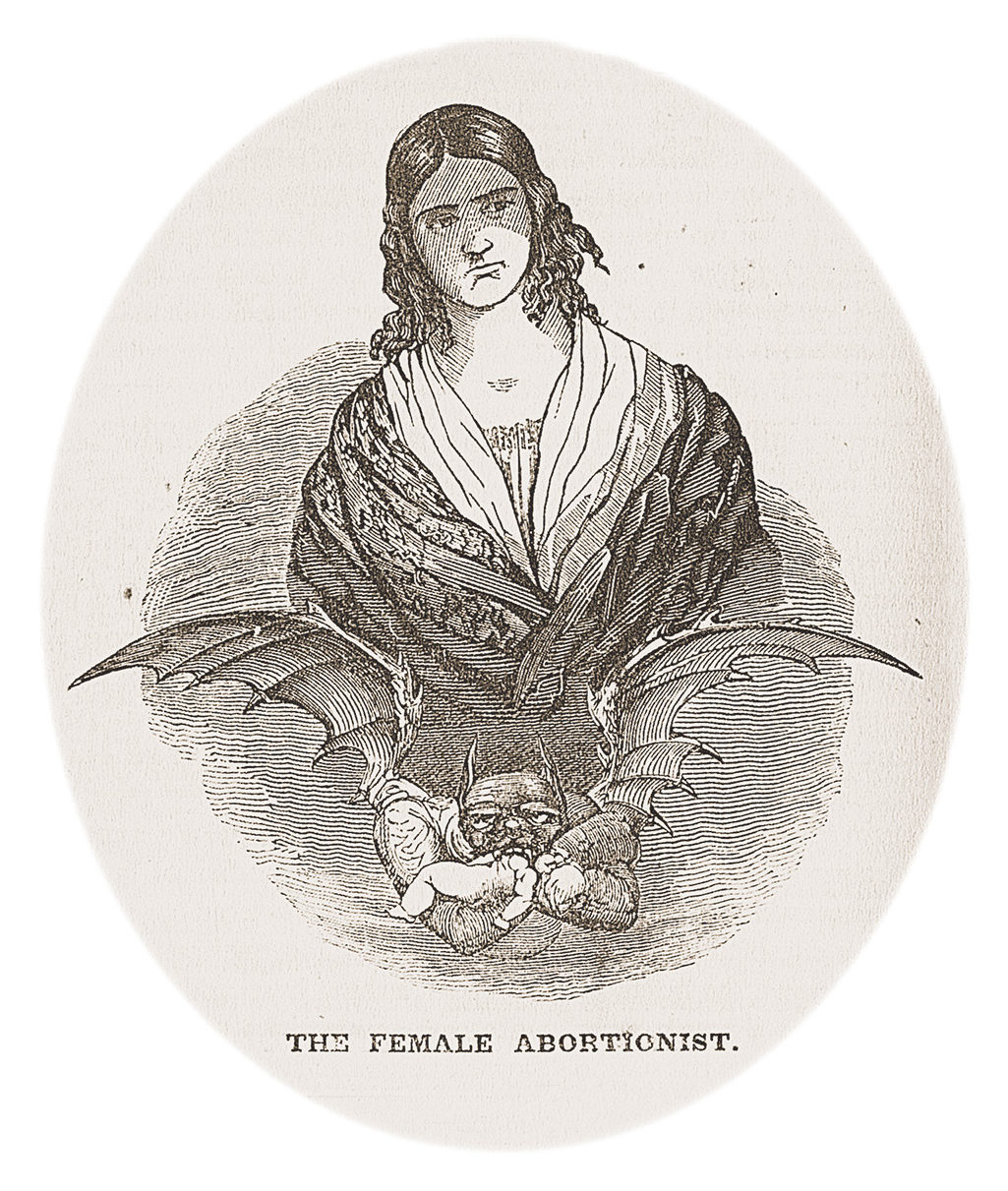

An 1847 caricature of an abortion provider. More often the practice was cloaked in euphemism. (Wikimedia Commons)

Nancy Ann Harris died on the 10th anniversary of her marriage to Frank. I’d like to think Frank was out of his mind with grief. When Delap arrived from the village three miles east to record Nancy’s death, the men probably said little. Yet I wonder how Delap knew of Nancy’s previous abortions. Maybe she didn’t conceal them from Frank, and in his grief and confusion, he told Delap.

Then again, it’s possible that Delap was the sort of country doctor who would, at the behest of favored clients, induce miscarriages. One regular from Milwaukee reported on such a rural colleague in a letter to the Wisconsin Medical Journal. The country doctor had confided that “we all do that kind of work when it is in a nice family and a girl has to be protected.” It wasn’t unusual for regular doctors to decry contraception and abortion to the public even as they provided the services covertly, at their discretion. If Delap had helped Nancy, maybe he felt compelled to represent the AMA’s stance in the footnote to her death.

Nancy’s death record is also stored in the state historical society’s digital archives, but she doesn’t appear in a search for “abortion.” Only 12 hits are returned for that term. Most link to photographs from prochoice marches in the 1970s and 1990s. None mention Dr. William H. Brisbane, a scowling, heavy-browed Baptist preacher who migrated north from South Carolina and founded a village 60 miles east of where Nancy is buried. Like Frank and Delap, Brisbane was a Civil War veteran and is lauded elsewhere in the state archives for his outspoken opposition to slavery. He was also a doctor, politician, and antiabortion crusader. Years before Nancy married Frank, Brisbane wrote and lobbied for a bill to make abortion a crime in Wisconsin.

In 1859, Wisconsin passed Brisbane’s bill and became the third state to criminalize abortion before quickening. The sentence for a woman who underwent an abortion was up to three months in jail and a $300 fine (about $10,000 today). For an abortionist, it was second-degree manslaughter. Neither the public nor the legislature had asked for the bill.

Brisbane acknowledged that his law was unlikely to be enforced—and for a while, it wasn’t. Still, as he wrote to an AMA colleague, even if making abortion a crime didn’t result in convictions, it would surely “have a moral influence to prevent it to some extent.” But it didn’t. Virtually no one outside the medical establishment—certainly not Nancy, her sisters, cousins, or friends—thought of abortion as a crime. No 19th-century American woman went to jail for having one. After all, the only way authorities could be certain that a woman had had an abortion was if she died as a result.

Even so, AMA physicians and politicians kept pushing. At the federal level, the 1873 Comstock Act prohibited, among other things, advertisements for abortion services and abortifacients. This resulted in an embargo on publicly printed information related to abortion and a growing perception of the practice as immoral. By 1880, every state had passed laws to prohibit terminating a pregnancy intentionally at any stage. Nonetheless, women kept seeking abortions in large numbers. In Woman’s Body, Woman’s Right (1976), Linda Gordon cites a judge’s estimate that in the state of New York alone, 100,000 abortions were performed annually throughout the 1890s. Soon after the turn of the century, other contraceptive practices became more widely publicized and available, with birth-control clinics opening in the 1920s and ’30s. America’s birthrate continued to drop until after World War II, when a resurgence in nationalism and a return to traditional gender roles produced a short-lived domestic revival and a baby boom.

On the Sunday morning after Nancy’s death, Frank would have left the tasks of bathing and dressing her to a female relative or friend. But he probably lifted her body into the coffin himself. Say the day was sunny, the ground lightly covered in snow when he hitched the horses. His two little girls rode with him in the wagon while his older daughters and son walked behind. They ferried the casket to the cemetery by the same route that Nancy might have taken to collect herbs. A bonfire had softened the newly frozen ground. A hole had been dug. A headstone was waiting. I would like to believe that Frank spent $5 he couldn’t really spare to purchase the headstone and have it engraved with Nancy’s name, birth and death dates, plus a tree of many branches to symbolize the reach of her life through eternity.

Soon after Nancy’s death, Frank, who had moved to Wisconsin from Ohio, moved farther west, to Nebraska. Abandoning the home that he and Nancy had made together might have been a measure of his sorrow. He, the Civil War veteran, didn’t die in my township. If any tombstones from my cemetery washed downstream in the flood of 1978, one was more likely Nancy’s than a soldier’s.

On the day I read aloud “Nancy Ann Harris” at our local historical society, I also learned of the fifth person listed as buried in the cemetery in my field: Florence Palmer. Nancy lived just south of my property; Florence lived just north. “Palmer” was Nancy’s maiden name. When Nancy died, Florence was 10—the right age to be Nancy’s niece by marriage. I wonder what the adults told her about Nancy’s death.

By the time Florence died in 1892, at age 26, the antiabortion laws that had swept the nation were finally being enforced. Midwives and irregular doctors who induced miscarriages were prosecuted. Inquests following women’s deaths from abortion were exposing them. Women’s conversations went deeper underground. Churches had joined the antiabortion movement. Prominent feminists joined it, too, because they believed that those who sought abortions had been victimized by men, and they felt women shouldn’t be forced into sex with its dangerous consequences. Nancy’s generation would have known far more about abortion than women in the three generations that followed. Perhaps they talked about it even more freely than women do today.

Florence’s death record lists the same cause as Nancy’s: puerperal peritonitis. But no triple-daggered footnote indicates the circumstance. Given that Florence already had four children and three stepchildren, it wouldn’t surprise me if she died from abortion-related complications. In rural Wisconsin in 1892, access to reliable information about “restoring the menses” was scarce. Regular doctors wouldn’t provide it, obscenity laws prevented its public dissemination, and the experienced women of the community who might have counseled Florence had taken their wisdom to the grave.

As I walk through the cemetery in summer, my boots make impressions in the soil. The ground is lumpy, damp, and thick with daylilies that never bloom because of the shade. I wonder how many bones are buried beneath me. I wonder where Nancy lies. And I wonder what she’d think of my portrayal of her, this marker I’ve created in place of a headstone.

I remember the eavesdropping woman’s comment: “That Nancy must have been something else.” If we crossed paths at the historical society now, after all I’ve learned, I wouldn’t hesitate to speak up. I’d point out that her judgment is rooted in misapprehensions of the 21st century. Nancy’s family and neighbors must have found her death tragic. The women who stood by as her casket was lowered might have thought, Poor dear. Maybe even, It could have been any of us. But they wouldn’t have thought the reason for her death shameful, any more than modern women would disparage a friend for being on the pill. Nancy Ann Harris wasn’t “something else.” Not for her time. Although the doctor’s footnote to her death was exceptional, she was simply an ordinary woman, if perhaps more forthcoming than the other women whose deaths he’d attended.