Searching for Amos Oz in Jerusalem

The acclaimed novelist, who died in 2018, translated Israeli reality

“Jerusalem seemed quiet and thoughtful that winter,” Amos Oz writes in his final novel, Judas (2016). “From time to time, church bells rang out. A westerly breeze stirred the tops of the cypresses.” It’s a lovely image, but Jerusalem wasn’t at all quiet and thoughtful when I visited this winter. It was noisy and bustling, even hectic. As a disgruntled American exclaimed in the baggage-claim hall of Ben-Gurion Airport, after the carousel broke and people climbed up to get their bags from the conveyor belt: “It’s chaos! There’s no law and order.” But you’d expect Jerusalem to feel more chaotic in the winter of 1959 and 1960, when Judas takes place, because back then the city was split by a hostile border. As Oz continues after the lines above, “Once in a while, a bored Jordanian sniper fired a stray shot toward the minefields and the wasteland that divided the Israeli from the Jordanian city.”

In 1949, when the War of Independence ended with a stunning Jewish victory, Jerusalem was divided in two; the new state of Israel got the western parts, and Jordan occupied everything else, including the Old City. Concrete walls, barbed wire, minefields, observation posts, and snipers separated the Israeli and Jordanian sections for nearly two decades. Then, after the Six-Day War of 1967, the entire city of Jerusalem came under Jewish control for the first time in more than 2,000 years—since the Maccabean revolt and subsequent Hasmonean period, a brief era of independence between 129 and 63 BCE. After the Hasmoneans, Jerusalem was ruled by the Romans, the Byzantines, the Arabs, crusaders, the Turks, and the British. And before the Romans, the Greeks controlled the city, and before them the Persians, and before them the Babylonians, and long ago, way before King David made Jerusalem the capital of a united Jewish kingdom around 1000 BCE, it was inhabited by the Jebusites, who built a small city on a ridge of Mount Moriah, where, according to legend, Abraham nearly sacrificed his son Isaac, and God created the world.

I thought about all this myth and history on a chilly Sabbath eve this January, as I walked from my hotel near the Downtown Triangle through the shuttered streets of West Jerusalem to the Jaffa Gate, into the labyrinthine Old City and to the Western Wall. And as I marveled at the boisterous celebration, I recalled how Oz casually sums it all up in his beloved memoir A Tale of Love and Darkness (2004): “The city has been destroyed, rebuilt, destroyed, and rebuilt again. Conqueror after conqueror has come, ruled for a while, left behind a few walls and towers, some cracks in the stone, a handful of potsherds and documents, and disappeared. Vanished like the morning mist down the hilly slopes.”

In the labyrinthine Old City of Jerusalem, Orthodox Jews hurry on David Street to a boisterous celebration of the Sabbath. (Randy Rosenthal)

Oz was born in Jerusalem in 1939, as Amos Klausner, and died in December 2018. His father, Yehuda Arieh, arrived in British-occupied Palestine in 1933, and his mother, Fania, in 1934. Yehuda Arieh was raised in Odessa before moving to Vilna, and Fania came from a wealthy family in Rovno (both Vilna and Rovno were then part of interwar Poland). In Jerusalem, Oz’s parents were frustrated intellectuals; Yehuda Arieh worked at the National Library on Mount Scopus, and Fania worked as a tutor. He could read 16 or 17 languages, and she could read about half as many. They spoke Russian or Polish when they didn’t want young Amos to understand, and taught him only Hebrew, which was still developing into a modern, living language—Oz’s great-uncle, the famous scholar Joseph Klausner, invented many new Hebrew words.

Raised in Kerem Avraham, a West Jerusalem neighborhood crammed with secular, petit bourgeois Russian Jews, Oz was brought up among poets, scholars, and books. In fact, when he was very young, his ambition was to grow up to be a book—not a writer, but a book. “People can be killed like ants,” he writes in A Tale of Love and Darkness. “Writers are not hard to kill either. But not books.”

Long before he began writing stories, Oz played a game with himself where he remade history, attempting to reverse the results of past wars. For instance, he “refought the great Jewish revolt against the Romans,” having Bar Kochba’s troops push Titus’s army all the way back to Rome, where they planted the Hebrew flag on top of the capitol. With the use of modern weapons, Oz “turned the doomed struggle of the defenders of Masada into a decisive Jewish victory with the aid of a single mortar and a few hand grenades.” As an adult, he felt this urge “to grant a second chance to something that could never have one” whenever he sat down to write a story.

The first half of A Tale of Love and Darkness reminds us how deeply the history of modern Jerusalem is tied with the pre-Holocaust anti-Semitism endemic to Eastern Europe. By the time Oz’s parents left interwar Poland, anti-Semitism was so bad, so violent, so humiliating that Jews actually considered emigrating to Germany—in 1933. Despite Hitler’s rhetoric, they thought Germany at least had law and order. Oz’s Aunt Sonia told him there was “fear in every Jewish home” in Rovno, “the fear that we never talked about but that we were unintentionally injected with, like a poison, drop by drop … the chilling fear that perhaps we really were not clean enough, that we really were too noisy and pushy, too clever and money-grubbing.” Overall, Aunt Sonia explained to young Amos, “there was a terror that we might, heaven forbid, make a bad impression on the Gentiles, and then they would be angry and do things to us too dreadful to think about.”

The Nazis arrived in Rovno in 1941. Over the course of two days, they and their collaborators murdered the city’s 23,500 Jews. Everyone Oz’s mother knew in Rovno was killed. A decade later, in January 1952, Fania committed suicide. She had lived through persecution and pogroms, avoided the Holocaust, survived the Siege of Jerusalem and the War of Independence, only to take her only life. She was 38. And intelligent, and beautiful, like an Ashkenazi Rita Hayworth. But she was plagued with migraines and insomnia. Doctors could never determine what caused her illness, but Oz suspects it was from an overabundance of romantic melancholy.

He was 12 at the time. About a year later, his father remarried, and they moved from Kerem Avraham to the more upscale Rehavia. A year after that, Amos left Jerusalem, went to live on a kibbutz, and changed his last name. He and his father never spoke about his mother again. But her presence pervades his best work like beets through borscht.

In Hebrew, the word oz means “strength.”

A few years into living at Kibbutz Hulda, in central Israel, Oz came across a translation of Sherwood Anderson’s story collection Winesburg, Ohio, and it blew him away. He realized he could write about what he knew—the relationships in his village—and did not need to live in Paris or New York to be an author. So he wrote Where the Jackals Howl and then Elsewhere, Perhaps. But his first bestseller was My Michael, published in 1968, when Oz was 29. It’s set in 1950s Jerusalem, and nearly everyone I spoke with in Israel was familiar with it—even the El Al airline security agent who interrogated me for more than an hour told me his mother named him Michael because of Oz’s novel.

Interestingly, Oz’s literary fame began well before he published his first book. It’s a story that could have happened only in nascent Israel. Its first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, fancied himself an intellectual and wrote long theoretical reflections on philosophical questions, his columns regularly published in the newspaper Davar. In 1961, when Oz was 21 and a committed Labor Zionist, he wrote a response disagreeing with Ben-Gurion on the subject of socialist equality. The prime minister himself responded with a long letter, sealing Oz’s name in the index of his collected writings. Soon afterward, Ben-Gurion summoned Oz to his office in Tel Aviv. There, at 6:30 in the morning, the 74-year-old prime minister lectured an understandably intimidated Oz about Spinoza. Later, Oz reflected that Ben-Gurion was no intellectual. Rather, he was a “visionary peasant,” bringing to mind the likes of Rasputin or a Hassidic master. “There was something primeval about him,” Oz writes in A Tale of Love and Darkness, “something not of this day and age. His simplicity of mind was almost biblical; his willpower resembled a laser beam.”

Today, I doubt Benjamin Netanyahu would invite an unknown 21-year-old to his office to discuss philosophy. Indeed, Israel has changed. Oz’s old neighborhood of Kerem Avraham has been “haredized,” now crammed with the black hats and skirts of the ultra-Orthodox Haredim, like neighboring Mea Shearim and Geula (where Shtisel, a show on Netflix, is set). The apartment building on Amos Street where Oz grew up now has a tiny synagogue on the ground floor. But in general, outside the Haredi areas, West Jerusalem is much more modern and cosmopolitan than when I first visited 10 years ago. Strolling through the posh outdoor Mamilla Mall feels like being in Santa Barbara or Capri. American accents are everywhere. And perhaps most significant, a high-speed train now runs direct from Ben-Gurion Airport to Jerusalem in just 20 minutes, physically and symbolically connecting the city with the rest of the world.

Previously, you had to take a meandering bus, and on my way there I wondered how the new train would make it up the western hills. But it didn’t go up them, it went through them, in an impressive series of long tunnels and high bridges, before settling into a station deep underground. “The station is actually a bunker,” Ari, a 30-something man in Orthodox garb, told me. He pointed out the thick, bank vault–like steel doors we passed as we made our way from the train to the city streets, several hundred feet above. “They say it’s the safest place in Israel,” he added. I told him I hoped it never had to be used as a bunker. Ari gave me a sober look and said, “Things are heating up.”

When I got to my hotel 30 minutes later, I learned that at the exact time I was talking with Ari, Iran had launched at least a dozen missiles at U.S. bases in Iraq, in retaliation for the assassination of the Iranian general Qasem Soleimani. Throughout the week I was in Jerusalem, the city was tense with expectation about how the situation would play out. As Adar, the young shakshuka-maker at Jahnun Bar, told me, “It’s like sleeping over a time bomb.”

Perhaps it wasn’t the best time to visit. Not just with the tumultuous political situation across the Middle East, but because on the night I arrived, Jerusalem was being lashed by a furious storm. Cold, dreary rain continued for days. “When it’s been raining Jerusalem makes one feel sad,” Oz writes in My Michael. “Actually,” he continues, “Jerusalem always makes one feel sad, but it’s a different sadness at every moment of the day and at every time of the year.”

It’s difficult to express the particular charge in Jerusalem’s atmosphere, but in her recent book The Passion of Jerusalem, Israeli author Michal Govrin pretty much nails it: “The Deep crouches in the bottom-most depth of Jerusalem, the navel of the universe and the eye of the storm.” Govrin is interested in the shifting mythology of the city, and Oz was too, though in a different, less biblical way. Rather, he was entranced by a mythic sophisticated Jerusalem he suspected existed just outside his neighborhood or in the era before he was born, that of internationally renowned scholars such as Martin Buber, Gershom Scholem, and S. Y. Agnon. Young Oz envisioned them socializing in the gardens of Rehavia, in cafés on Ben Yehuda Street, and in the lobby of the King David Hotel.

In another affluent part of Jerusalem, the German Colony, I met Dalia Cohen-Knohl for coffee. Cohen-Knohl has a PhD in literature from Haifa University and has published three novels and several plays in Hebrew. She attributes Oz’s status more to the time period in which he first published than the quality of the work itself. From the 1950s through the 1970s, she explained, Israel was suffused with a spirit of communal Zionism, where authors praised the new state ruled by the Labor Party. Then, after the 1967 war, when Israel occupied the Palestinian territories, and during which Oz served with a tank unit in Sinai, there was a break from this perspective. Young authors like Oz and A. B. Yehoshua started to express different views, opposing the Zionist socialist-collective mentality. My Michael came out in 1968, during this shift.

My Michael introduced “a new voice,” Cohen-Knohl told me, “speaking about the individual, which was innovative then.” Oz became “the leading author,” she continued.

She mentioned the Romanian intellectual Mircea Eliade’s idea of how everyone goes back to their mythical time. “For Oz,” she said, “that mythical era is Jerusalem before ’67.” That is, when Jerusalem was “very small, very naïve, separated from the West Bank and Old City.” In My Michael, in Judas, and in A Tale of Love and Darkness, Oz “writes with longing and nostalgia about this period.”

And yet, though she thinks Oz is “very talented; his Hebrew is so rich, so exquisite,” Cohen-Knohl also said that in some of his novels, Oz “doesn’t touch your heart” because “he walks beside the emotion,” a phrase I adored.

After meeting with Cohen-Knohl, I walked through Talbiya to see Oz’s second and last home in Jerusalem, on Ben Maimon Avenue in Rehavia. And in a bookstore across the street, I met Cassandra Gomes-Hochberg, a book critic and editor for The Jerusalem Post. Originally from Brazil, she wrote in a recent eulogy on the first anniversary of Oz’s death that, for her, Oz was “the translator of Israeli reality.” Oz’s books have been translated into 45 languages, more than any other Israeli writer, so it makes sense that many people abroad would get to know Israeli culture through his work. His wide appeal must also have had to do with the power of the writing itself; after all, he’s often referred to as a prophet. And as someone who meticulously studied the Hebrew Bible during an arduous process of converting to Judaism, Gomes-Hochberg believes that Oz is indeed like a prophet, speaking in the “same harsh and wise tones of Jeremiah, Isaiah, and Amos.”

Later, at a bar in Nahalat Shiva, a lively neighborhood of quaint pedestrian streets, Gomes-Hochberg clarified that Oz writes prophetically only in his political journalism. She spoke of his 2004 essay “How to Cure a Fanatic,” but it occurred to me that his most crucial essay could be “The Meaning of Homeland,” published in 1967 soon after the Six-Day War (and later collected in Under This Blazing Light), in which he bluntly expresses his pro-Zionist but anti-occupation position. During that critical time in modern Israeli culture, then, Oz published both My Michael and “The Meaning of Homeland,” two works with different approaches that launched him as Israel’s preeminent author and ultimately turned him into a liberal symbol more than an artist.

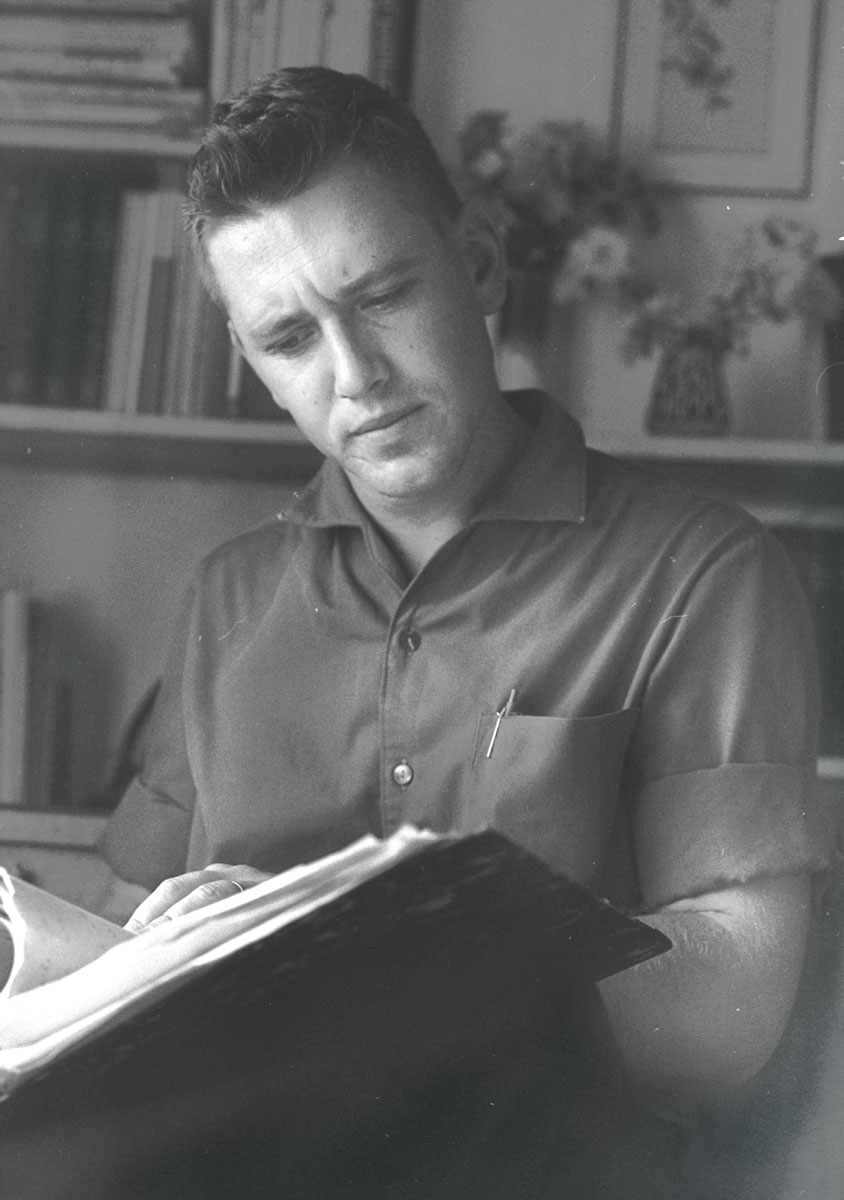

Oz wrote “with longing and nostalgia” about Jerusalem before the 1967 war, when the city was “very small, very naive, separated from the West Bank and Old City.” (Wikimedia Commons)

Yet like most writers I spoke with in Jerusalem, Gomes-Hochberg also admitted that Oz’s prophetic style of political writing grated on her. (In fact, many Israelis expressed purely negative feelings about Oz’s work, though they did not want to say so publicly—Israeli literary culture is small.) After all, nobody likes a prophet, and a prophet is never welcome at home. So, in Israel itself, Oz is often perceived as arrogant, acting as if he alone possessed the truth, specifically the truth about how to resolve the Israel-Palestine conflict. He consistently advocated for a two-state solution, ceding the West Bank to Palestine in what he termed a “divorce.” And in “The Meaning of Homeland,” he wrote prophetically:

As I see it, the confrontation between the Jews returning to Zion and the Arab inhabitants of the country is not like a western or an epic, but more like a Greek tragedy. It is a clash between right and right (although one must not seek a simplistic symmetry in it). And, as in all tragedies, there is no hope of a happy reconciliation based on a clever magical formula. The choice is between a bloodbath and a disappointing compromise, more like enforced acceptance than a sudden breakthrough of mutual understanding.

Israelis on the right loathe Oz for this position of pragmatic compromise. It’s been this way since the 1970s, especially after the conservative Likud Party came to power and, in response, Oz helped found the organization Peace Now. His 1983 book In the Land of Israel, in which he reported from the West Bank settlements, made him even more unpopular with the right. And now that Israeli politics has swung even further right, he’s despised by ideologues on both sides. Because Israel, like the United States, is now a place of ideological extremism, where anyone who presents a nuanced perspective, one that captures the complexities of reality, is suspect. The far left resents Oz for his unapologetic Zionism and clear-eyed support of the military—as he writes through a character in Judas:

Am I saying that we do not need military might? Heaven forbid! Such a foolish thought would never enter my head. I know as well as you that it is power, military power, that stands, at any given moment, even at this very moment while you and I are arguing here,

between us and extinction.

And yet the far right reviles Oz for his opposition to the West Bank settlements and his support of a Palestinian state, for which he’s seen as a traitor. A Judas.

Oz lived at Kibbutz Hulda until 1986, then moved to Arad, in the Negev Desert, and spent the final years of his life in Tel Aviv. But in his last novel, he returned to the Jerusalem of his youth. That nostalgic city of Judas no longer exists. Today’s Jerusalem hardly resembles the city of that first generation of Israelis to be born there, when the only concern was survival and when expansion, much less occupation, was unthinkable. And yet Jerusalem is so old that it can’t really change. Because outside the new Jewish areas there is still what Oz calls, in A Tale of Love and Darkness, “the other Jerusalem”:

a city of old cypress trees that were more black than green, streets of stone walls, interlaced grilles, cornices, and dark walls, the alien,

silent, aloof, shrouded Jerusalem, the Abyssinian, Muslim, pilgrim, Ottoman city, the strange, missionary city of crusaders and Templars, the Greek, Armenian, Italian, brooding, Anglican, Greek Orthodox city, the monastic, Coptic, Catholic, Lutheran, Scottish, Sunni, Shi’ite, Sufi, Alawite city, swept by the sounds of bells and the wail of the muezzin, thick with pine trees, frightening yet alluring, with all its concealed enchantments, its warrens of narrow streets that were forbidden to us and threatened us from the darkness, a secretive, malign city pregnant with disaster.

Yes, Jerusalem is still like that.

And sometimes, just sometimes, when dusk is falling, and the cypress trees become silhouettes against an indigo sky, and the street lamps cast weak yellow light on the white stone walls, and all you hear is the trilling of blackbirds, or the pealing of church bells or the hypnotic call to prayer, Jerusalem still does seem quiet and thoughtful.