Second and Long

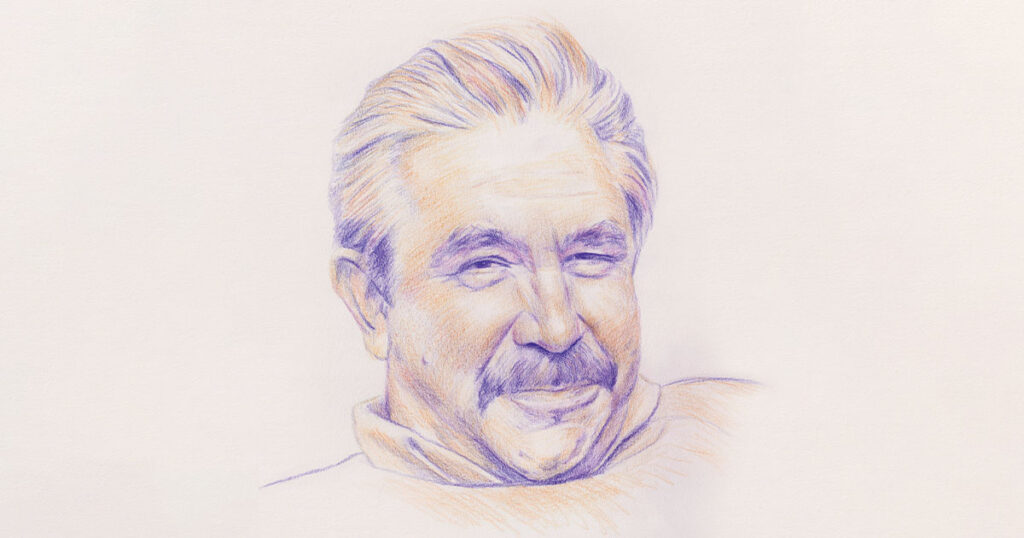

Why did James Whitehead—poet, fiction writer, and onetime college football player—fail to complete a successor to his celebrated first novel?

In 1971, Alfred A. Knopf published a debut novel by a young poet from Mississippi, who prior to becoming a writer had played offensive tackle on the Vanderbilt University football team. Eponymously titled Joiner, the book is narrated by Eugene “Sonny” Joiner, like its author a native of the Magnolia State, as well as a keen student of philosophy, religion, history, literature, and art. Joiner is himself a former college football star, good enough to have played a year in the NFL with the fictional Dallas Bulls. Though he tosses the n-word around at will, he is otherwise enlightened on the issue of civil rights and has, with a rifle, dispatched a murderous racist redneck to rid the world of such a scourge. He has killed one other man in self-defense using only his fist. When we meet him, he’s out of the NFL, teaching at the Unitarian Progressive School for boys, residing in a Fort Worth motel with his mistress, gorging himself on peanut butter and graham crackers, while planning a return to Mississippi to wreak havoc at the wedding of his ex-wife and an erstwhile high school teammate.

One of the novel’s two epigraphs is taken from Finnegans Wake—“Hit, hit, hit!”—and like that famously elusive novel, Joiner is all but impossible to summarize, since it lacks anything resembling a traditional plot. It ends where it begins, with Sonny Joiner in Fort Worth mulling mayhem. What compensates for the absence of a conventional story line is the gargantuan personality of the narrator, a man who, while nurturing many a grudge, practically bursts with lust for life. He seems to have read almost everything, which has led to his having an opinion about everything, and he peppers his observations with references to Greek mythology, Dante, and Faust. The novel’s authenticity comes not only from Sonny’s knowledge of football but also from the disparity between his intellectual pursuits and his comically accurate phonetic transcriptions of expressions familiar to any native Mississippian of a certain age: “WaChont?” (What do you want?), “wuffashit” (worth a shit), “mummernem” (momma and them).

Published in the heyday of postmodernism, the novel was widely, and often ecstatically, acclaimed. In The New York Times Book Review, R. V. Cassill found that the author had somehow managed “to sound the full range of the Deep South’s exultation and lament. … His tirade makes an awesome, fearful and glorious impact on the mind and ear.” Theodore Solotaroff, in Esquire, wrote that Joiner “is one terrific account of animal male nature at bay, and it is [the author’s] feeling for the creaturely pleasure and grace and wisdom of virility and of the abuse and perversion that are inflicted on it that makes his book so luminous and moving.” Time magazine called the book “a terrific creation.” It was the kind of novelistic debut most young writers can only dream of. Anticipation for its follow-up ran high.

The 35-year-old author’s name was James Whitehead. Though he lived and wrote for another 32 years, the second novel never appeared.

When I met Jim in August 1981, I was 24 years old, about to embark on what I dared to dream would be my own journey as a novelist. I was a first-year graduate student in the MFA program at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, where Jim had been teaching since 1965. I had been in town for three and a half days when the newly installed phone in my one-bedroom apartment rang for the first time. I assumed the call was from my parents, since I hadn’t given the number to anyone else and didn’t know a single person in the state of Arkansas.

“Is this Yarbrough?” a gruff voice asked. I admitted that it was. “How the hell long have you been here?” A couple of days, I responded, before asking whom I was speaking to. “It’s Whitehead,” the voice growled. “Were you intending to come over here and introduce yourself or not?” I assured him I’d love to come over—it seemed dangerous not to—so he gave me directions to his house and said he’d expect me in a few minutes.

Though I would learn that he was nearly always the first person to welcome the new poets and fiction writers, it turned out that he was especially eager to meet me. From looking at my application and letters of recommendation, he had gleaned that, like him, I’d grown up in Mississippi and gone to college on a football scholarship. He even knew that I played the same position he did. Also, we had each earned a B.A. in philosophy, then an M.A. in literature. I might as well have had Literary Son scrawled on my forehead. What I didn’t know then was that he and his wife, Gen, had four real sons, as well as three daughters, and that all of their children would go on to earn advanced degrees and forge careers in fields such as banking, medicine, and education. One of his colleagues would tell me about seeing him some years earlier in the aisle at Safeway, pulling one grocery cart and pushing another, both carts piled full. “He must have had three or four gallons of milk in those things,” his colleague said, “and just as many cartons of eggs.” Nothing, I would learn, came more naturally to Jim than being someone’s father.

When I parked at the curb in front of his house, he was sitting on the front steps. Football players become especially good at assessing one another’s bodies. My eye told me that the man who rose from those steps stood somewhere between six-four and six-five, weighed between 285 and 300, and had a pair of tree trunks for thighs. The man walking toward him stood a shade under six-two and weighed 210—far below my college playing weight of 235. In the years since I’d quit football, I’d retained my athlete’s appetite and ballooned to 275 before realizing I was eating myself to death. Over the previous six months, I’d lost weight the only way I knew how, by running it off. I regularly ran eight or 10 miles a day and had once run 14.

“I heard you played tackle,” Jim said, almost crushing my hand. “You look more like a free safety.” I told him I used to be a lot heavier. “You must have been,” he said, then led me inside.

I don’t know where we sat that day to talk, but my guess is the living room. Over the next three years, I would usually be in that room only when he and Gen would throw a party for a visiting writer and invite all the students. The room I would get to know best was the finished basement, where a couple of other grad students and I would frequently watch basketball and baseball with him. (Oddly, I don’t recall watching a football game with him in the three years I lived in Fayetteville; my guess is that he became so intense when watching football that he was reluctant to let anyone join him.) Another room I would get to know very well was his study, where he made me present myself for a one-on-one session after each formal workshop discussion of my manuscripts. The basement I would come to associate with beer, cheer, and camaraderie; the study, with anxiety, frustration, and bruised egos—generally my ego but sometimes, I suspect, his, too.

I don’t know if we drank anything that August day or not, though it seems like we would have, since we nearly always did. He talked to me about the MFA program, of which he was justifiably proud. Having recently celebrated its 15th anniversary, it had already nurtured a number of acclaimed writers, including Barry Hannah, Ellen Gilchrist, Frank Stanford, and C. D. Wright. He assured me I would receive lots of attention, just like all of them had, but he also cautioned that I should not “succumb to the fallacy” that I was primarily there to learn technique. I was there, he said, to learn how to live the writing life, to keep the written word central to my existence.

He went a little further in discussing his colleagues than I would go when I became a professor myself. The novelist William Harrison, he told me, was “a practicing hard-ass”; whether that was a good thing or a bad thing he did not say, but he did observe that having played football might come in handy when dealing with Bill. He said that John Clellon Holmes, whose workshop I’d be taking in the fall, was a very sweet man, a “high school dropout who’s fiercely well-read”; he also said that Holmes had written a Beat novel before his friend Jack Kerouac had, that “John’s was better than Jack’s,” and that the publishing industry had “put Holmes on a shelf and tried to turn him into a goddamn relic.”

Knowing how little confidence I had then, how scared I was that I might not measure up to his and my other professors’ expectations, I imagine that I tried to leave before long, afraid I would be taking up too much of his precious time. If I did make such an effort, I know exactly what his response would have been because I would hear it so many times during the coming months and years: Sit back down, Yarbrough. We’re not finished yet. It was late afternoon when he finally led me through the dining room and kitchen and out a side door.

When we stepped into the driveway, he said, “I hope you didn’t think this was a command performance? I didn’t mean to drag you over here against your will.” At first, I thought he was joking. But his face suggested otherwise. He’d crossed his big forearms over his massive chest and was looking deadly serious. I was going to see that expression many times. Jim Whitehead was about nothing so much as revision—not just revision of sentences, paragraphs, or entire manuscripts but also of utterances and actions, of slights and omissions. His pursuit of perfection was relentless, and everything was subject to constant reevaluation. As hard as he could be on those around him, he was much harder, I have always believed, on himself.

I told him I was honored to be invited over, which was true, but that I didn’t want to be a bother, because I knew he had his own writing to do. His broad face relaxed. He smiled, almost knocked me down with a slap on the shoulder, warned me not to be a stranger, then stepped back inside and softly shut the door.

The list of 20th-century American writers who published a widely acclaimed first novel and never produced another is not long. But neither is it unimpressive. Among those it includes are Ralph Ellison (Invisible Man), J. D. Salinger (The Catcher in the Rye), and Leonard Gardner (Fat City). All those writers made significant contributions in at least one other genre: Ellison wrote two formidable books of essays; Salinger authored two collections of stories that are still being read; Gardner worked as a journalist and wrote numerous screenplays and teleplays, also producing several episodes of NYPD Blue.

A few years ago, after New York Review Books reissued Fat City, I agreed to moderate an event with Gardner at a Boston-area bookstore. A day or two prior to the event, my wife and I gave a party for him, at which most of the guests were writers two or three decades younger, who for the most part knew neither his 1969 novel nor the John Huston film based on the book. But one of the guests that night, who happened to be staying with us for a few days, was the Arkansas novelist Donald “Skip” Hays, with whom I’d gone to grad school. Toward the end of the evening, Hays placed himself next to Gardner on a couch and talked to him for more than an hour. Gardner, Hays told me later, seemed stunned that he knew the novel so well and had admired it for so long. Before the event at the bookstore, as we waited in the employee break room, Gardner asked me what questions I might be planning to pose. I’m ashamed to admit that I told him I planned to ask why, after such a memorable debut, he’d moved on to other pursuits rather than writing another novel. I am not going to relay his reaction. But suffice it to say I did not pose the question and neither, to my relief, did anyone in the audience.

Ralph Ellison, however, could not avoid that question. He began his much-anticipated second novel shortly after the National Book Award–winning Invisible Man appeared. According to John F. Callahan, his friend and literary executor and the coeditor of The Selected Letters of Ralph Ellison, he continued to work on the novel until his death in 1994. To put that in perspective, he started the book prior to the 1954 Supreme Court decision that ruled separate-but-equal public schools unconstitutional, and he was still working on it more than a year into Bill Clinton’s first term as president. In the Selected Letters, the earliest references to the novel-in-progress are full of enthusiasm and optimism. In a 1955 letter to the novelist Paul Engle, he says he expects to complete the novel in 1956. His spirits have flagged considerably by the time he writes to his close friend Albert Murray in April 1960, stating that “most of what’s being published shouldn’t be, and although I am damned disgusted with myself because of my failure to finish, I know nevertheless that it’s better to publish one fairly decent book than five pieces of junk.” Four years later, in a letter to the literary critic Joseph Frank, he hopes that “some miracle” might enable him to have “this novel put away by summer.” In a 1969 letter to the jazz musician John Lucas, he says that “the fact that I haven’t been publishing fiction doesn’t mean that I haven’t been writing,” then goes on to say that he lost “a good part” of the novel during a fire two years earlier. Perhaps the most revealing comments come in a 1983 letter to the literary theorist Kenneth Burke, with whom he had a friendship that lasted half a century. Ellison wrote about the difficulty of “just making a meaningful form out of my yarn. … There are all kinds of interesting incidents in it, but if they don’t add up it’ll fall as rain into the ocean of meaningless words.”

My guess is that by the time I asked Jim Whitehead about his follow-up novel, he had been hearing the question for the better part of a decade. We were at his house, sitting in his study. I’d submitted a long story to his spring semester writing class. The previous semester in John Holmes’s workshop, the story had been critiqued by Ken Kesey, who’d been doing a week-long stint as guest writer. Kesey hadn’t been satisfied with the ending but had otherwise praised the story, so I’d made some minor tweaks and was pleased with it, especially since it had gone over well with the other students in Jim’s class. Jim himself said he had “a few reservations” but that we’d discuss those privately. I wasn’t worried. The other story I’d submitted to John’s class had already been accepted by a good literary magazine. I would soon be a published writer, and I intended to submit the revised story to The New Yorker.

The private conference in Jim’s study probably lasted around three hours. But those three hours felt like several lifetimes. The 35-page manuscript that he brandished at me was bleeding ink. He’d circled some words, drawn lines through others, posed questions in the margins of every page: top, bottom, left, and right. On the backs of some pages he’d written critical essays.

“What you need to understand, Yarbrough,” he said, “is that being a Mississippi writer’s like being an Irish writer. You’ve got to get everything, beginning with the landscape, right. Now, you set this narrative in central Jackson, which as you know is my hometown, on an August afternoon. You’ve got this 65-year-old man, who we already know has had at least one heart attack, leaving his house—which you tell us is ‘within a stone’s throw’—and that’s a cliché, and not a good one, there are no good clichés—‘of the zoo.’ Which means that—‘in a quarter of an hour’—he walks damn near the length of Capitol Street, a distance of three and a half miles, which you seem clueless about, to the porn store where he picks up his nasty magazines. Does he sweat along the way? No, of course not, though it’s bound to be about a hundred degrees. You say the porn store’s on”—he consulted my ink-stained manuscript— “ ‘the corner of a side street three blocks from the Old Capitol Museum.’ What side street, Steve? ‘Three blocks’ from the damn museum is West Street. Since he’s walking east and crosses the street, then takes a right, that means we’re at the southeast corner of South West Street.” With my story he slapped a meaty thigh. “You’ve replaced St. Andrew’s Episcopal Cathedral with a goddamn porn store? Give me a break!”

My main character might not have been sweating on an August afternoon in Jackson. But by the time Jim got through with me that February day, my shirt was soaked, though it was around 20 degrees in Fayetteville and snowing. I had never felt more forlorn.

My suspicion is that when he played football, Jim was the kind of lineman who’d smash into you, drive you 10 yards downfield, knock you down, and stand over you to make sure you didn’t get off the ground, while secretly hoping you might try to. But after the whistle blew, he’d offer you his hand, pull you up, and pat you on the butt in the time-honored gesture of a magnanimous victor toward a vanquished opponent. Which is essentially what he did to me that day. He told me to “buck up,” that I had a lot going for me, that my prose was vivid and energetic, that I wrote good dialogue and had a subversive sense of humor, and that anybody who’d run off 65 pounds in six months was not scared to work hard. “Sometimes,” he said, “you just have to go back to the first sentence and start over. That’s what this story calls for.”

Over the next week or two, I would see that some of the problems Jim identified could be easily solved. There was no reason to be specific about the home’s exact location in the city, or what month it was, or precisely where the porn store stood. But because he made me question every word in the story, I saw what he and Kesey and everyone else had failed to see—or if they had seen it, they didn’t mention it, possibly for fear of inflicting too much damage on a young writer: my main character was as flat and straight as a Delta dirt road. Ask not what he might do, or what he might want to do, or why he might want to do it. Ask instead what he would do, and you could safely bet the house that he would do it. The problem was that I didn’t really want to know the character. I only wanted to look down on him.

But these realizations lay ahead. That snowy afternoon, I thanked Jim and told him I would read all his comments carefully and try to solve the story’s many problems. Then, just to show I was as interested in his work as he was in mine, I asked him when his novel-in-progress, a sequel to Joiner tentatively titled Coldstream, would be published.

“The novel’s right over there,” he said, pointing at several stacks of legal pads, each about two feet high, resting on a table in the corner. “As to when it’ll be published, Yarbrough, that’ll happen when I know it’s ready. And not a goddamn minute before then.”

I need to acknowledge that I quickly came to love Jim Whitehead. A couple of times he saw me in the hallway at the university and deduced from a single look that I was dead broke. On at least three occasions that I recall, he reached into his pocket, pulled his wallet out, and handed me $20. He bought me beer after beer and meal after meal and offered sound advice about romantic entanglements. Once, when I went to his faculty office to complain about being denied a summer stipend that the department’s guidelines suggested I qualified for—and without which I couldn’t take a literature class that I badly needed—he said, “Sit right here while I go raise hell.” He returned in five minutes to say that I had been granted the stipend and that the department chair wanted to see me and offer his apology. Nearly every one of my friends in the program could tell similar stories. We were all members of Jim’s extended family.

Still, I often found him maddening. I took two fiction workshops from him and never once heard him pronounce my own work or anyone else’s “ready.” Everything, to hear him tell it, required extensive revision, and those revisions, if fully executed, would probably have turned numerous short stories—some of which were good and some of which weren’t—into massive novels that would never be finished.

In a particularly memorable instance, after Skip Hays’s MFA thesis novel The Dixie Association was accepted by Simon & Schuster with a tidy sum attached, Jim attempted to convince Hays that the book was nowhere near ready for publication. “Jim called me up,” Hays recently told me, “and said, ‘Yeah, Skip, the book’s okay. But it could be a hell of a lot better. You can’t just be satisfied because they say it’s good.’ ” He told Hays he’d be happy to read the manuscript as many times as needed and that he believed they could get it ready in a year or two. Hays politely declined, and the book went on to become a finalist for the 1985 PEN/Faulkner Award, losing to Tobias Wolff’s novella The Barracks Thief. Hays does credit Whitehead for having told him three years earlier to drop his original third-person approach and let the main character tell the story himself, a decision that he considers pivotal.

A cynic might wonder whether Whitehead’s reluctance to pronounce a fiction manuscript ready was an indication that he felt threatened by his charges’ potential successes. I’ve seen many manifestations of this during the 41 years I spent in academia and at writers conferences. But nobody who knew Jim Whitehead and witnessed the lavish attention he paid to his students’ welfare would suspect him of that. Something else was going on in his case, and it had to do with the very different attitudes he took toward fiction and poetry.

Like most novelists I know, I have started writing a number of books that, for one reason or another, I didn’t finish. I have no regrets about any of those decisions. In fact, I shudder to think that my name might have appeared on a couple of those I gave up on. But giving up was not in Jim’s nature. He wrote like he played football: to the final whistle.

In the fall of 2007, four years after Jim’s death, the Missouri State University literature professor and critic James S. Baumlin and the graduate students in his research methods class were granted access to some nine and a half cubic feet of material from Jim’s archives. Among those materials, Baumlin and his students found numerous drafts—some complete, some partial—of both Coldstream and Bergeron, the second and third novels of a projected trilogy. Jim, Baumlin found, “was an obsessive reviser, who would give a day’s worrying to a single word or rhythm.” While acknowledging that this process worked well for Jim when he wrote poetry, Baumlin says that when he turned to fiction, it “led to near-paralysis—to hundreds (literally) of drafts, most starting from scratch.” In a recent email exchange, Baumlin told me that he viewed Jim’s struggles with Coldstream as “tragic.”

That was also the view of Jim’s longtime friend and colleague William Harrison, who had been his classmate at Vanderbilt and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Bill was comparatively prolific, publishing nine novels, three collections of short stories, and a volume of essays; he also wrote numerous screenplays and teleplays, including the script for the James Caan movie Rollerball, among 1975’s highest-grossing films. One day in the fall of 1982, Bill called me into his office to tell me that the novel I had been working on was going nowhere and that I ought to focus for the time being on short stories. “Failure,” he said, “has consequences, Steve. Just look what’s happening to our friend Jim, who’s been writing that second novel since you were in fourth or fifth grade.”

Had Joiner represented James Whitehead’s only artistic achievement, I might see his inability to complete the second novel to his satisfaction in a tragic light as well. But like Ralph Ellison, J. D. Salinger, and Leonard Gardner, he found other forms for artistic expression, publishing three superb collections of poetry, each of which took more than a decade to write.

I know the novels of Robert Penn Warren better than I know his poetry. But I’ve read plenty of both, and they seem, not surprisingly, to emerge from the same aesthetic. I also feel that way about the poetry and novels of Sylvia Plath, Michael Ondaatje, Joyce Carol Oates, James Dickey, Jim Harrison, and Ron Rash. James Whitehead’s poems, however, seem to spring from a completely different aesthetic than the unruly one that produced Joiner. It’s an aesthetic rooted in reverence for traditional poetic forms, especially the sonnet. The poet and critic Angela Ball, a longtime champion of Jim’s poetry, told me that “form in Whitehead does more than shape language in order to preserve it—it’s a type of radical restraint, like schooling adolescent boys in ballroom dancing. Form holds back emotion the better to express it, the way a good actor convinces us of a limp by attempting to hide it.”

To my mind, the crown jewel in Jim’s oeuvre is his 1979 collection, Local Men. More than half of the 50 poems in the book are sonnets or variations on the sonnet. Although the subject matter in these poems is in many instances similar to that of Joiner—lost love, violence, country music, and race—the voice is as straightforward and matter-of-fact as Sonny Joiner’s is frenzied and baroque. It’s as if Jim had to put himself in a straitjacket to deliver his most powerful and deeply felt work.

I have long subscribed to the belief that many if not all short stories have more in common with a lyric poem than they do with a novel: chief among the properties they share is the need to employ suggestion and implication to great effect while working with the awareness that from the moment you write the opening line, your options are dwindling, the walls closing in. Based on my own experiences with Jim in his study, I suspect he was incapable of writing a short story, and as far as I know, there is no evidence to the contrary. But I also suspect it would please him to know that for the better part of 40 years, during the opening session of nearly every class I taught devoted to short fiction, I handed out a poem from Local Men.

Before giving it to my students, I’d tell them nothing except that it was written by a poet from Mississippi and that it was published during the 1970s. All but a small fraction of my teaching career occurred at schools in California and Massachusetts, where the students were not likely to have had any familiarity with the kinds of shotgun shacks that could be found in the Mississippi Delta until almost the end of the 20th century; nor, sadly, were they likely to know much more than cursory facts about the civil rights era. The other thing that they may not have known, depending on whether they’d read as much poetry as I wanted my fiction students to have read, is that any 14-line poem is likely to be related to the sonnet, a form long associated with love.

ABOUT A YEAR AFTER HE GOT MARRIED

HE WOULD SIT ALONE IN AN ABANDONED SHACK

IN A COTTON FIELD ENJOYING HIMSELFI’d sit inside the abandoned shack all morning

Being sensitive, a fair thing to do

At twenty-three, my first son born, and burning

To get my wife again. The world was new

And I was nervous and wonderfully depressed.The light on the cotton flowers and the child

Asleep at home was marvelous and blessed,

And the dust in the abandoned air was mild

As sentimental poverty. I’d scan

Or draw the ragged wall the morning long.Newspaper for wallpaper sang but didn’t mean.

Hard thoughts of justice were beyond my ken.

Lord, forgive young men their gentle pain,

Then bring them stones. Bring their play to ruin.

After they’d had around 10 minutes to study the poem, I’d ask them to tell me everything they knew, or thought they knew, about the speaker and the experience he is describing. I’d also ask them to tell me what puzzled them. One of my goals was to make them realize how much they “knew” without having to be explicitly told. The other was to make them aware of the gray but infinitely fertile ground between what they knew and what they’d considered.

Usually someone would say that the speaker sounded happy but also seemed to be feeling sorry for himself because he was no longer the main thing on his wife’s mind. Someone might have noted that the speaker mocks himself for “Being sensitive, a fair thing to do / At twenty-three,” during a time when he was both “nervous” and “wonderfully depressed.” Somebody nearly always cited the phrase “my first son born” as evidence that the speaker has subsequently fathered at least one other son and possibly more children after that. If I asked whether the speaker might be sitting there “all morning” because he’s unemployed, every student I’ve ever had said no. If I demanded evidence, they would invariably say that he just sounds too comfortable to be in economic distress.

At this point, somebody would usually wonder who abandoned the shack, why it was abandoned, and why no one else had moved in. “Weren’t the people who used to live there probably Black? Maybe sharecroppers?” That question led inevitably to a discussion of why “the dust in the air was mild / As sentimental poverty.” The students would give the speaker credit for understanding that for the people who used to live there, poverty was real, not “sentimental,” but there was always a student or two who wondered whether the speaker knew that at the time or came to understand it later. That usually led somebody to observe that the two-line prayer at the end would suggest he didn’t know it until later but wishes he had and is mad at himself that he didn’t.

It’s the beginning of that final stanza, though, that was the most challenging and rewarding to discuss. My students were nearly always mystified by the opening line: “Newspaper for wallpaper sang but didn’t mean.” But sooner or later, somebody would suggest that the newspaper is “singing” about events that don’t mean anything to the speaker because he’s white and doing okay. If I was lucky, and more often than not I was, someone would suggest that since he’s in a shack, maybe the wood’s rotten, which the phrase “ragged wall” implies, so the people who used to live there stuffed newspaper into the holes in the wall to keep the cold out in winter, and the wind made the paper whistle or sing, but that doesn’t mean anything to the speaker because he can go home to a better place.

A single word—the noun at the end of the next line—always led to the finest moments in our discussions of the poem. Most students mistook ken for kin. But usually at least one would raise a hand to say, “Doesn’t ken mean something different, like your ability to understand a concept?” This would be the point at which I’d reveal a bit more about the poet, then tell them what he would surely have known about the homophone before electing to end the line with it. Ken, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, was first used as a causative verb, meaning to make known, declare, confess, acknowledge, during the Old English period. Its first use as a noun, indicating the range of one’s vision or the ability to grasp a concept, can be traced to Middle English. I’d tell them, too, that the word kin originally encompassed not only one’s immediate relatives but sometimes all the members of a particular clan. I’d conclude by suggesting that even for the students who were familiar with the meaning of ken, there was an instant echo of kin, and that once an echo occurs in the mind of the reader, a pack of bloodhounds can’t chase it away. In this case, ken is a rich word in a rich little poem that illustrates some of the many ways in which poems and stories accrue meaning.

Jim had much in common with another writer of both fiction and poetry whose work means a lot to me: Jim Harrison. They were born a little more than a year apart, and both grew up far from the literary capitals (Harrison spent his childhood in various parts of rural Michigan). Both became college instructors in the mid-’60s, but Harrison lasted only a short time in his position, whereas Whitehead remained a professor for more than 35 years. Their first books of poetry came out a few months apart, Harrison’s in 1965, Whitehead’s in 1966. Both published their first novels in the fall of 1971 and received appreciative New York Times reviews three weeks apart. But even when you adjust for the fact that Harrison lived 11 years longer, the difference in their outputs, as well as the fate of their work, could not be starker. Harrison published 12 novels, nine collections of novellas, 14 books of poetry, two essay collections, a memoir, and a work of children’s literature. It is no exaggeration to say that he was one of the most prolific and celebrated American writers of the past half century.

If one considers only output and reputation, it would be impossible not to label Harrison a huge success and Whitehead at best an underachiever or at worst a failure. But if I find myself succumbing to that kind of thinking—as I sometimes do when the 12 books with my own name on them begin to seem woefully inadequate, given how many years I’ve been alive—I come back around to Ralph Ellison’s statement that “it’s better to publish one fairly decent book than five pieces of junk.” Is there an element of bitterness in his argument? Unquestionably, and no small measure of envy either. Resignation, too. But I think there is also an element of wonder. Did I really do that? Was that me? How could something so marvelous have happened? I would be surprised if Jim Whitehead did not sometimes entertain those thoughts.

Last December, in the aftermath of Jimmy Carter’s death, a New York Times article by Carter biographer Douglas Brinkley noted how voracious a reader the 39th president had been. According to Brinkley, some of the authors Carter revered were Dylan Thomas, William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, and Alice Walker. Another was Ralph Ellison. Yet another—a poet who inspired Carter to try his own hand at verse—was James Whitehead.