Southern Cassandra

Lillian Smith was a writer and a radical who called out her region’s lies about sex and race

Like all truly aggravating people, Lillian Smith refuses to go away. That is, the corporeal Lillian Smith may have died in 1966, but her words refuse to go away—words that described white privilege before that was a phrase, words that seem newly relevant in an era when cell-phone videos of police brutality perpetrated on black people are impossible to unsee.

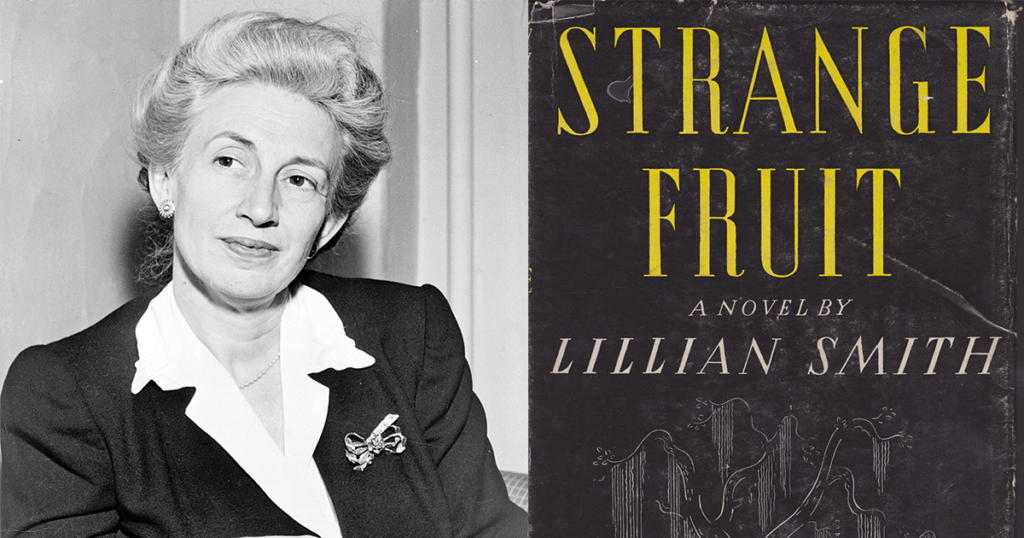

Who is Lillian Smith? Unless you’re an academic or a women’s studies major, you’ve probably never heard of her. It’s understandable; she’s ancient history. We are nearly three-quarters of a century past Strange Fruit, her 1944 novel about a doomed interracial love affair in a small south Georgia town. The book sold three million copies worldwide and was made into a major Broadway play. Even international fame, it seems, is ephemeral. So let us review.

Smith was a bomb thrower—a writer, an educator, a social activist, and a native southerner who came from “the best people”—a phrase she used a lot—but who betrayed every value of her social class. From 1925 to 1948, she ran a summer camp in Clayton, Georgia, for the daughters of the South’s white elites, where, in the course of evening “creative conversations” about growing up, she led her young ladies to understand that pretty much everything they’d been told about race and sex was a lie—quietly planting subversive seeds in the bosom of well-bred white southern families who thought they had sent baby sister off to some vaguely progressive place to learn archery and such.

The publication of Strange Fruit launched her career as an author and public intellectual. Yet while her reputation flourished outside the South, her fellow southerners treated her to a staggering amount of vitriol. Mississippi newspaper editor Hodding Carter, that journalistic icon of the civil rights era, called her “a sex-obsessed old maid”—and he was on her side, more or less. Former Georgia governor Eugene Talmadge called one of her books “a literary corncob.” Ralph McGill, the sainted Atlanta Constitution journalist, called her “a modern, feminine counterpart of the ancient Hebrew prophets”—an unflattering comparison to hairy guys with bad personal hygiene that was, I am convinced, a thinly veiled mockery of Smith’s lesbianism. Because she was that, too: a woman who loved another woman in an era when homosexual acts were a felony in all 50 states.

Smith’s crime was forthrightly linking the subjects of race and sex in an era when nice people didn’t publicly talk about either. Her critics said she had a prurient interest in linking those two subjects; she argued there was no way you could unlink them: the whole rationale for Jim Crow was the supposed need to protect the “purity” of white women. She suggested that lynching a black man was the kind of thing that could give a white man an erection. She described a culture that turned its sons into mama’s boys and taught its daughters to sublimate their own sexual hunger with coconut cakes and banana puddings. Guilt, she said, was the South’s biggest crop—flourishing like mildew in the region’s “combination of a warm moist evangelism and racial segregation.” She looked at the white South of her generation and saw a society that had fallen in love with its own soul rot.

She said what everybody knew but nobody wanted to say: “Even its children knew that the South was in trouble,” she wrote in her 1949 memoir and meditation on race, Killers of the Dream. She outlined the nexus of race, sex, and economic and political oppression long before Ferguson, Missouri, erupted into flames or #BlackLivesMatter started trending on Twitter:

I know now that the bitterness, the cruel sensual lips, the quick tears in hard eyes, the sashaying buttocks of brown girls, the thin childish voices of white women, had a great deal to do with high interest at the bank and low wages in the mills and gullied fields and lynchings and Ku Klux Klan and segregation and sacred womanhood and revivals, and Prohibition.

She condemned the silence of white churches when it came to racial oppression 14 years before Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” (“The decade before [my generation was] born, a thousand Negroes were lynched. … And in church, not a word”), and she pinpointed the parallel obsession with so-called sins of the flesh, sex in particular: “Their religion was too narcistic [sic] to be concerned with anything but a man’s body and a man’s soul. … [T]hey plunged into our unconscious and brought up sins we had long ago forgotten.”

And in an era of Eugene Talmadge and Strom Thurmond, she called the South’s political leadership what it was: “hotheaded, uninformed, defensive, greedy men, unwilling to accept criticism.” Sound familiar?

Not surprising, then, that in Smith’s day the people who most needed to hear her words found them enraging, or that she regularly fielded obscene phone calls and bomb threats, or that in 1955 a a fire during a burglary at her house destroyed decades of writing and correspondence. People who advance our moral evolution are never popular. Think of contemporary activists like Alicia Garza or DeRay Mckesson. Or Nelson Mandela, or Mahatma Gandhi. Think about Cassandra.

In the ancient Greek story, Cassandra is the daughter of King Priam of Troy, blessed by Apollo with the gift of prophecy. She is a priestess in his temple, and beautiful, the story goes, and one day Apollo puts the moves on her. When she turns him down, he gets mad and curses her: she will have the gift of prophecy, but nobody will ever believe her.

Cassandra tells her fellow Trojans that kidnapping the beauteous Helen from her native Sparta and bringing her back to Troy will lead to a ruinous war. Nobody listens. She tells them that Greek warriors are hiding inside that huge wooden horse outside the city walls. She’s nuts, they say, and drag it in anyway. In some versions of the story, she goes insane; in others, she is raped, or sold off to the victorious Greeks as a concubine. She bears two children, who are murdered, and then she is murdered. I wonder: Did she ever get to say, I told you so? And then I think: I bet they really hated her.

Smith was the daughter of a king, too—or its functional equivalent in the small northern Florida town of Jasper, where she was born in 1897. Her father owned a turpentine mill and traded in lumber. Though not rich by Gilded Age standards, the Smiths sat atop the social heap. It was a conventionally religious family, and Smith’s parents considered themselves enlightened on racial matters for their time: they would shake hands with black people they knew and disdained the use of the N word in favor of the polite term, colored people.

The outbreak of World War I caused the collapse of the turpentine and lumber empire Smith’s father had built, and the family descended into genteel poverty. Selling the family home in Jasper, the Smiths downsized to their summer home in north Georgia, re-outfitted several rustic cottages, and turned the enterprise into a hotel. Lillian studied at the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore with the idea of becoming a concert pianist, but soon realized she lacked the talent to make music her career. Instead, she spent her 20s helping her parents run their hotel, which morphed over the years into a girls’ camp, and working in various secretarial and teaching jobs, including three years of teaching music at a Methodist school in China. In 1925, with her parents in poor health, she reluctantly agreed to run the girls’ camp. In her absence, her father had hired Paula Snelling in the athletics department. Laurel Falls Camp for Girls became Smith’s lifelong home, and Snelling became her life partner.

A Columbia University graduate with a master’s degree in psychology and a minor in English literature, Snelling partnered with Smith in 1936 to found a literary magazine called Pseudopodia, one of several publications that marked the Southern Renaissance of the 1920s and ’30s. By then, Smith’s interest had turned from music to literature. Not all of her early efforts survive, and only one was submitted to publishers until Strange Fruit. (Smith borrowed the title from the song Billie Holiday made famous, though she always maintained that in her hands it referred not to lynching, as the song does, but to the people produced by the South’s racist culture.)

With its violence, interracial sex, graphic language, and even the hint of a lesbian love affair, Strange Fruit promised to be an instant best seller, and it was. Outside the South, critics were mostly kind: W. E. B. Du Bois, who reviewed it for The New York Times, admired its complex and poetic portrayal of how money, race, class, and sex intertwined in a small southern town—“caught in a skein … that only evolution can untangle or revolution break.” Diana Trilling, writing in The Nation, saw its larger message. The book, she wrote, “is so wide in its human understanding that its Negro tragedy becomes the tragedy of anyone who lives in a world in which minorities suffer.” Black and white reviewers alike, though, found its black characters one-dimensional or uncomfortably stereotyped. (Today, you can see pretty much the same praise, and the same criticisms, on the book’s Amazon page.)

As Smith’s literary reputation grew, so did her civil rights activism. She was a confidante of King’s, a frequent correspondent with the major civil rights leaders of that era, and a regular contributor to the mass-media platforms of her day: Time, Life, Look, The New York Times, Reader’s Digest, The Saturday Evening Post. When Strange Fruit was banned from the mail for being obscene (it contains the word fuck), her personal friend Eleanor Roosevelt quietly saw to it that the ban was rescinded.

Like a lot of deeply moral people, Smith could come across as naïve. “She expected people to do the right thing, even when it was totally contrary to their perceived best interest,” says Atlanta actress Brenda Bynum.

Bynum has thought a lot about Smith: she portrays her in a one-act show she has taken to colleges, book clubs, and literary festivals around the South. Like many southerners of her generation, Bynum had grown up with a vague impression of Smith “as some wicked thing we weren’t supposed to talk about.” But she’s always been interested in “notional” southern ladies—inconvenient women who challenged the status quo of their day. (Southern history seems to have had more than its share—Mary Chesnut, Ida B. Wells, Fannie Lou Hamer, Rosa Parks.) So when Bynum was asked by Nancy Smith Fichter, Smith’s niece, to develop a presentation on her aunt for a literary festival a few years ago, she quickly realized that she had found a sister of her soul.

I saw Bynum’s show in 2014. At 63, I am a few years younger than she. My vague impression of Smith had nothing to do with faint rumors of sexual depravity; I thought of her as some do-gooder white liberal from the 1960s who had pretty much had her day. Aren’t we past this? I thought.

And then Bynum walked onstage, and over the next hour she revised my thinking. Actually, one moment did it. It came when Bynum—in a conservative pantsuit and pearls, a Buckhead matron c. 1964—read a review of Killers of the Dream by Atlanta Constitution publisher Jack Tarver.

“Lillian Smith has written a new book, and brother, is it a stinker,” Tarver starts off with breezy disdain. He proceeds to ignore Smith’s ideas in favor of trashing her intelligence. “Don’t get me wrong: Miss Smith is entitled to her racial views, a trillion light years to the left of center though they may be”—which tells you right there how far to the right southern liberals of the day really were. The book didn’t have chapters, he wrote, but “orgasms.” He even made sure to warn those who might be tempted to buy the book out of salacious interest: it would be a disappointment to “connoisseurs of the pornographic … as well as to those of Miss Smith’s following who have labored under the delusion that somewhere in her fervor-packed being there was room for a trace of talent.”

Bynum finished reading. Then she let silence collect in the room while her audience absorbed the full measure of Tarver’s casual contempt and while she, as Lillian, let the psychic hurt sink in, in the way that shocking pain can take a while to register.

That was when I got it—what it must have been like to be an original thinker born female in the Deep South of the early 20th century. For any woman of my generation who has ever been mansplained, who has known the sudden silence that falls on a group of men when she ventures to express a sharp opinion, who has been generously offered a raise by men who forgot to mention they underpaid her in the first place, who has heard her own ideas repeated back to her as if they were somebody else’s, who has ever lain awake wondering how much her own lack of self-confidence has sabotaged her ambitions—how much worse was it then?

Dear Lord, I thought. What she suffered.

“She was a true believer,” Bynum told me later. “People like that rub almost everybody the wrong way sooner or later.”

And here is where I have to make a confession: Lillian Smith rubs me the wrong way.

Some of my complaints are minor. She could be intellectually arrogant (an occupational hazard among writers). “Now, the SNCC kids as a whole are OK—I mothered them through their first three years and I know,” she wrote in one letter, and goes on to say that King “isn’t too bright as a politician.” In another letter, she describes Julian Bond as “such a fine boy.” (Well, he was fine, but not in the way she meant.) It is interesting to speculate what those two men privately thought of her political skills. What we do know is that when King was jailed in Albany, Georgia, in 1962, Smith wrote to one of her former campers in that city, attempting to exert some behind-the-scenes influence. King “is one of my friends and a most wonderful guy,” she wrote. “Couldn’t you and Bob and your friends do something to make officials in Albany see that this can be worked up into a world scandal and poor old Albany will pay for it for years. … Atlanta has eased its hot spots by a few upperclass people like you, quietly talking to the right officials.”

We’ll never know how much difference that letter made, though it’s worth noting that three days into King’s 45-day jail sentence, somebody quietly paid his fine for disturbing the peace—an outcome that King, for strategic purposes of his own at the time, had not even wanted.

She could be downright grandiose. “In my own opinion, some day I rather think Strange Fruit and Killers of the Dream plus my other writings will give me the Nobel Prize,” she wrote to a Hollywood film agent seeking to buy the rights to the novel in 1961—a deal that was never made because Smith thought the amount offered was insultingly little. “I know my worth; I know my historical value to this country,” she wrote.

I’m sorry, but no. Strange Fruit does have its moments—its lyrical descriptions of the southern landscape, its deadly accurate portrayal of the suffocating oppressiveness of small-town southern evangelical religion when it is wed to parental expectations—but those are outweighed by its embarrassing failures: black characters who speak like they stepped out of a minstrel show, and a plot that would have us believe that a black woman, a graduate of Spelman College, had no higher ambition than to be one particular white man’s lover and the mother of his child.

Still, arrogance and grandiosity I can forgive. A less-than-great novel I can forgive. What I find hard to forgive is that, as keenly aware of injustice as she was, Smith was oblivious to her own elitism. She saw her role as a member of the South’s upper crust as bringing the gospel of racial equality to the other “best people” of the South, who would then go forth and quietly instruct the rednecks on how to behave. As the daughter of six generations of southern rednecks, as a white southerner from the south side of Atlanta whose schools were integrated while the “best people” on the other side of town sent their kids to expensive private schools, whose neighborhood pool closed rather than integrate while country club pools elsewhere remained open and lily-white, I find that patronizing. I’m not the only one: literary critic Malcolm Cowley, one of several prominent reviewers who gave Strange Fruit middling marks as a literary accomplishment, noted in 1944 that Smith seemed to think “that the ‘best people’ in the South could take steps toward solving the racial problem, if only the poor whites wouldn’t interfere.”

This elitism was more than just an intellectual failing on Smith’s part. It fits neatly into a narrative of the South that you can still find given unquestioning acceptance in the pages of The New York Times and a million lazy stereotypes—and it’s one that southerners like me find deeply offensive. It’s the view that white southerners come in three flavors: the educated elite (a tiny minority), the antidemocratic aristocracy, and the brutish poor. It is given expression in news stories that equate “southern” with “white”—as if black people cannot claim the South as their own by virtue of sweat equity alone—and it ignores great swaths of southern history: the contributions of its white yeoman farmer class and a significant, if largely ignored, history of political dissenters and progressive social movements. It’s a simplistic view of the South that is to the immensely complicated real thing what Hee Haw is to the collected works of Johnny Cash. I can’t lay the blame for this entirely at Lillian Smith’s feet, of course, but it’s fair to say that her writing did nothing to dispel any stereotypes.

But flawed as she was, struggling as she did to arrive at an accurate assessment of her strengths and limitations, she was clear about one thing. “When Strange Fruit was published things were terrible racially; not one person but me in the South had ever spoken up publicly against segregation; now, all decent people do,” she wrote in 1961. She rightly took credit for shattering the code of silence and denial among white southerners of her generation when it came to race. “I didn’t do it all; but I did the symbolic creative job that had to be done by some white artist.”

Toward the end of her life, she could sense the clouds of obscurity already gathering. “When writers about ‘race’ are discussed,” she wrote, “I am never mentioned; when southern writers are discussed, I am not among them; when women writers are mentioned, I am not among them; when best-sellers are discussed, Strange Fruit … is never mentioned. … Whom, among the mighty, have I so greatly offended!”

It tells you a lot that she had to ask. Like all prophets, she never really grasped how deeply unpopular Cassandras are to the people they live with, how far many people will go to keep on living an imaginary life instead of the complicated reality they have inherited. Four centuries ago, it was easier to pretend that slavery was the inevitable result of having darker skin; today, it’s easier for white people to pretend that their granddaddy’s college education or their parents’ VA home loan or the nice neighborhood where they bought a house had nothing to do with their lighter skin.

Academia never forgot her, though. There was a 1986 biography of Smith by LSU historian Anne Loveland, and in 1993 University of Alabama historian and women’s studies professor Margaret Rose Gladney edited a collection of Smith’s letters. The books were seeds that sprouted with a new generation of feminists and women’s studies scholars. Today, literary festivals are held in her honor; book awards are named after her. Craig Amason, director of the Lillian E. Smith Center at Piedmont College, Smith’s alma mater, says that 36 dissertations have been written about her since her death, with the number increasing every year. To today’s women’s studies majors, she’s a symbol—a talented writer right more often than she was wrong, catapulted to fame and then banished for speaking the truth. Nevertheless, she persisted.

And she was prescient. “There is always a dark underside to every age: a festering ill-smelling slum where man’s enemies and errors breed,” she said in a speech given at Atlanta University. For American democracy, the greatest danger is “the demagogue: the man who deliberately betrays the people; the man who scares them, calling fire, when there is no fire; who tells the people they are free to break the law, free to trample other people’s rights, free to slough off their conscience and their reason and behave like mad men when they want to.”

That was the tragedy of the South Lillian Smith knew: the majority “gave [its] support, every time, to the cheap, foul-mouthed demagogue who appealed not to our reason and conscience but to our anxiety, who begged us to return with him to the past, a past that never actually existed.” The rest, she said, “either [did] nothing or something totally irrelevant to the situation. And in a crisis that is a dangerous kind of behavior.”

Then she added this: “But it is not too late.” Resistance matters, she told them. Individual voices matter. Find good leaders, she advised, and build them up; support them with your money and time and labor. We can pick the winners, she said, and “the winner names the age.”

That was in 1957. Nine years later, she was dead. Today, I imagine her in some kind of literary afterlife, reunited with her sister Cassandra. They sit together, those two aggravating, inconvenient women, slipped free of the temporal stream and finally able to see past, present, and future happening simultaneously. I imagine them with arms entwined, watching as Troy burns and the Selma marchers are clubbed and Philando Castile is shot for no reason—and then ahead, to see the future winner who names our present age. Maybe if they were here, they’d tell us how it all turns out. But they’re not, and the suspense is excruciating.