Sisters and Rebels: A Struggle for the Soul of America by Jacquelyn Dowd Hall; Norton, 690 pp., $39.95

Why should we care about three sisters who never achieved lasting fame? Elizabeth, Grace, and Katharine Du Pre Lumpkin are largely unknown today. None of them married a president. They weren’t heiresses of Gilded Age tycoons or stars of the silver screen. Although contemporaries of Amelia Earhart, they did not make headlines by flying off on daring adventures. Their stories were not even tragic in the classical sense—they did not die young.

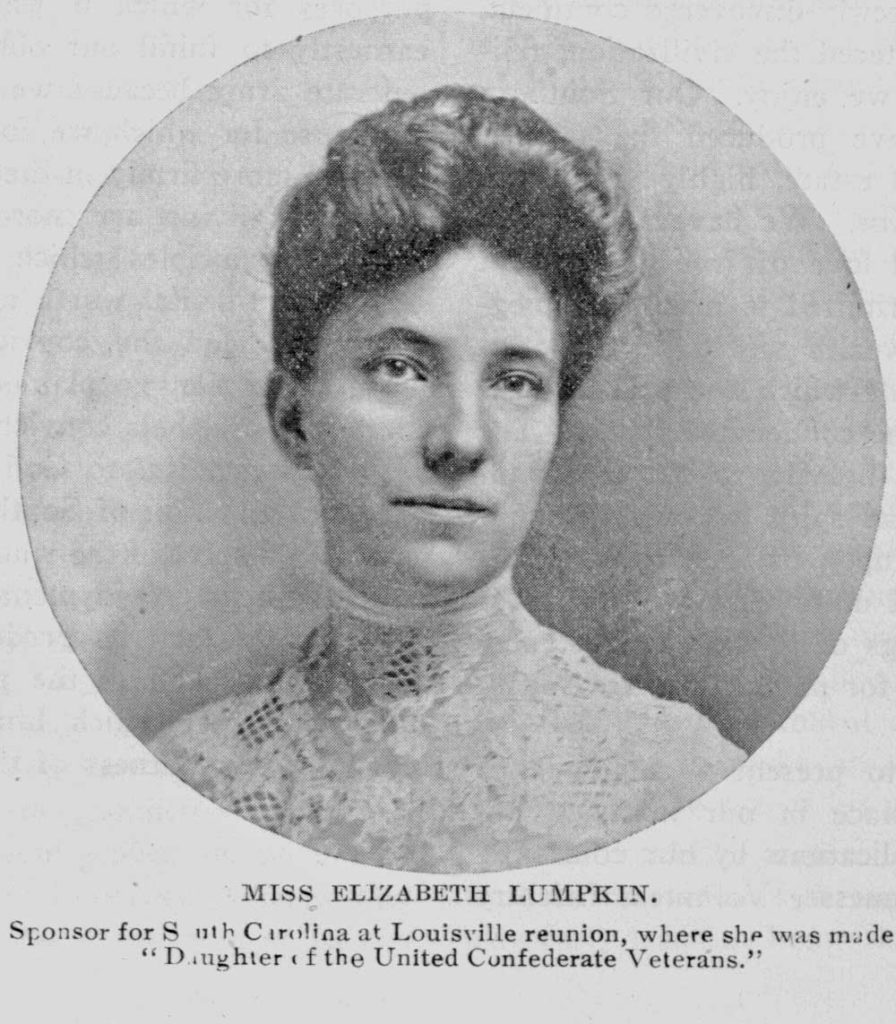

But the Lumpkin sisters do matter, because their lives tell a regional tale of southern female identity. Born in the New South during the late 19th century, they were raised in a highly literate family devoted to Lost Cause mythology, which celebrated the Confederacy as a noble defense of a way of life. Although the eldest, Elizabeth, became a recognizable southern matron, the two other sisters charted distinctly different paths: Grace made a name for herself as Communist labor activist and writer; Katharine pursued an academic career, becoming a pioneer in southern women’s history.

The real story here concerns the difficulty that these educated women had in breaking free from their troubled relationship to the South. The Lumpkins present an uncomfortable mixture of rebellion and acceptance: rebellion against southern racism and the requirement of female subordination; acceptance of the conservative notion that it’s a woman’s duty to protect her family’s honor. Though Grace and Katharine fled to the North and became outspoken political critics and sexual radicals (and even the more conservative Elizabeth craved the public stage as an orator and actor), none of them escaped the weight of the past. Family secrets haunted these women, no matter how far they ranged from their southern roots. Jacquelyn Dowd Hall’s triple biography conveys the tortured feeling of a southern novel, for one reason: the sisters never truly freed themselves from the powerful hold of the family’s patriarch, William Lumpkin.

Having lived through the Civil War and Reconstruction, William Lumpkin imbued his seven children with the lore of the family’s antebellum plantation grandeur. When the Lumpkins moved from Georgia to Columbia, South Carolina, in 1898, he aimed to find the ideal neighborhood and send his children to the right schools. He trained them to exploit their education, social connections, and especially their imaginations so as to stand out wherever they went. Two sons entered politics, another the Episcopal ministry. For their part, the daughters sought literary fame. Their individual reactions to their upbringing may have differed, but the common denominator was making a name for themselves as southerners.

Katharine (1897–1988) wrote an autobiography, The Making of a Southerner (1946), which initially drew author Hall to her biographical project. But it is what Katharine neglected to address in her book that stands out. She may have had a sexual relationship with the brother who became a minister, and she ignores her father’s dark past as a member of the Ku Klux Klan. Her autobiography is less a truthful account of her own life than an attempt to tame the past and make it usable for southern women hoping to escape the tired script of Gone With the Wind.

But the reticent nature of the book, and the veil of secrecy that enshrouds all three sisters, puts off Hall at first; having interviewed Grace and Katharine in the 1970s and 1980s, she waited until now to finish the book. Her need to return to the unfinished project made her approach the subject as a family story. Hall acknowledges that the truth remains elusive, calling the sisters “the most intimate of strangers,” as she probes hidden corners of their past, revealing secrets they wished to forget. And she faced roadblocks. Katharine, for example, burned many of her personal papers and attempted to destroy a diary of Grace’s. She likewise sought to erase the personal record of her long relationship with her lover Dorothy Douglas, an academic at Mount Holyoke and an outspoken international economist of a communist bent later targeted during the Red Scare.

As girls, the Lumpkin sisters lived the southern fantasy of white supremacy. The eldest, Elizabeth, was a popular orator at Confederate veteran rallies, perpetuating myths of the Lost Cause drummed in by her father. The entire family joined the ranks of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, United Confederate Veterans, and children’s auxiliaries. As a member of the Klan, William defended the use of violence to promote white supremacy during Reconstruction and its aftermath.

Elizabeth (1881–1963) played the southern belle at her “Confederate wedding,” another grand stage on which her father’s wounded ego could shine. She married a wealthy but less refined southerner, Eugene Glenn, a physician who became a chronic alcoholic. Her darkest secret was disappearing to a Richmond clinic, far from her North Carolina home, for what appears to have been a mental breakdown while her husband lay dying. After recovery, she took up the life of a productive widow with four children, became the business manager of her husband’s hospital, and earned a law degree. She pursued a passion for acting in local theater and wrote a massive novel that was never published.

The most adventurous sister was Grace (1891–1980). After moving to New York City in 1924, she was swept up in the radicalism of socialism, the Communist Party, and the labor movement. She lived as a bohemian in Greenwich Village, married a working-class activist named Michael Intrator, 12 years her junior, and befriended the infamous Whittaker Chambers. Grace and Michael shared a house with Chambers and Esther Schemitz (her former roommate), who became Chambers’s wife. Rumors spread of Chambers’s homosexual exploits, suggesting he was sleeping with Grace’s husband.

Grace wrote potboilers and proletarian novels. In her first short story for The New Masses, her narrator was, Hall writes, a “déclassé planter’s daughter very much like herself.” Although her fiction was always riddled with self-references, her most famous novel, To Make My Bread (1932), was loosely based on the martyred labor activist and balladeer Ella May Wiggins, who led a 1929 mill strike in Gastonia, North Carolina. Wiggins was nothing like Grace: no formal education, nine children, and pregnant when murdered. Though Grace killed off her female heroines, her well-received novel made her into a “left-wing literary star.”

Grace was clearly troubled. At the time of her marriage, she lied about her age, 41, shaving off seven years. She trusted Chambers, the most untrustworthy of men. Her writing relied on mastering formulas she knew would please her audience. As her marriage collapsed and the Cold War set in, the once-Marxist radical became a religious reactionary and informer for the FBI, to which she secretly provided information on her sister Katharine.

Katharine, a labor scholar, began as an activist in the YWCA and enjoyed a respectable academic career. She earned an MA at Columbia and a PhD in sociology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. She later taught at Mount Holyoke and then spent two decades as director of research at Smith College’s Council of Industrial Studies and the Institute of Labor Studies until her life was turned upside down by the Cold War crackdown on suspected Communist sympathizers.

Katharine was the most bookish and private of the sisters and the willing gatekeeper of family secrets. Her last book, a biography of Angelina Grimké, was probably more therapeutic for her than her memoir. Grimké, born into a wealthy family in South Carolina, went north (like Katharine) to become a famous antebellum antislavery lecturer. Lumpkin’s biography focused on the years of isolation after her subject achieved fame, plus her tortured relationships with a controlling older sister and husband. It was as if Katharine had transferred her own psychic pain to Grimké.

Hall’s book raises a dilemma. Does biography normalize three women who were anything but “normal”? Uncovering what they really thought and felt means navigating a maze of family secrets and self-deceptions. Grace is a shapeshifter: she reinvents herself several times and spends her final days in less-than-genteel poverty back in Columbia. Katharine prefers scholarly objectivity, distancing herself from emotional wounds. She, too, returned to the South, spending her retirement years in Charlottesville, Virginia, before dying of cancer. There are no happy endings.

Hall’s skillfully drawn biography of the Lumpkin sisters is dramatically told, and all three women are worth knowing. But a feeling lingers that much of what made them tick remains hidden. Was it family shame, festering resentments, faded dreams, or something else that caused them to repress or rewrite the past? Their deepest secrets may well have died with them.