Starving

The feelings of yearning and loss, when faced with an empty nest, can manifest in striking ways

I’m always hungry these days. Not just mildly peckish (like, may I have a few more string beans, please?) but ravenous—I have a black hole of an appetite, and nothing seems to fill the gaping space. As a result, I watch myself closely so as not to gain too much weight—which leaves me hungrier still.

“Is it metabolic?” I ask my doctor during this year’s physical. “Maybe something to do with menopause?”

“Could be,” she says. “Hormones are tricky little monsters. But your blood work’s consistent, and your sugar’s terrific, so we can rule out diabetes. Overall, you look healthy to me.”

Oh. That’s good, right? Except for the hunger, which, let me tell you, is consuming, chewing me up from the inside out. It’s a high-pitched whine, a ceaseless I want! that reminds me of my daughter, Celia, as a toddler—the round face like a perfect ice-cream scoop, the stubby arms and legs—how she trotted from place to place, touching everything. How she flushed with astonishment at the world around her and wanted to own the entire thing.

I just want to eat the entire thing. I’m starting to wonder if it’s connected to my Stuff Problem.

The Problem is just that—the belongings I’ve amassed over the years, the ones I go on collecting. You might not know it to look at my house—I’m not at the hoarding stage (yet)—but as with food, I have to guard against this tendency.

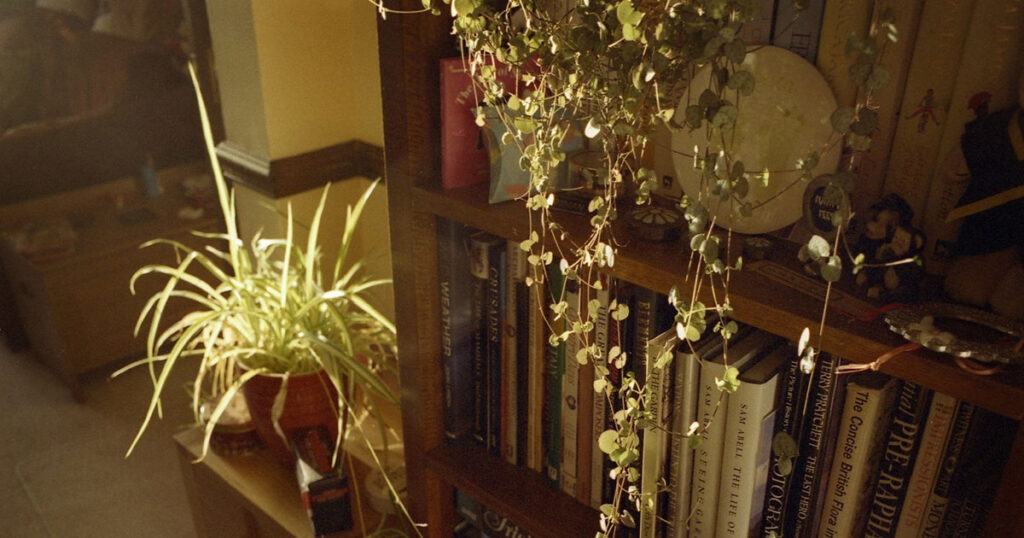

Despite recurrent purges, my house remains stuffed like the plushest of cushions. Ten thousand framed photos of my daughter, the books (so many, teetering-full bookcases in every room), the art covering my walls, the lumpy ceramic projects from my clay habit. There are Celia’s old toys and special outfits I can’t bear to lose—never mind that she’s finished college and left home, moved to a darling town an hour away where she’s working to overfill her own tiny apartment.

My husband, Steven, enables me, his pack-rat tendencies permitting my own to flourish like a field overflowing with wildflowers, which sounds lovely until the flowers grow sentient, then trip you and eat you while you’re flailing among the roots. To my punk and new wave and ’60s folk albums (because vinyl is king!), add Steven’s punk and classic rock and so on, until together we crowd an old wardrobe. There’re the hundred houseplants, all happy and verdant, so in winter when everyone lives inside, it’s tough to turn around without bumping into a fern or rubber tree, the dumb cane and monstera.

Our house looks lovely until you bump one ficus or frame out of place. Then it’s duck and cover, every woman for herself.

My friends can’t relate.

“I don’t want presents for my birthday. I mean it, not a crumb,” says Deborah, who’s lately been trying to pawn off her superfluous possessions on the neighbors, and who said she’ll never get a pet because she doesn’t want another thing to care for. My friend, with her husband out of work and her special needs son, has more than enough to manage. “And definitely no more adorable objects to dust or clean around,” she adds, so I take the pretty antique perfume bottle I’d planned to gift her and set it on a shelf in my bathroom.

“I like emptiness,” says Maureen of her nearly naked home. “I donated the last vases and candlesticks on the mantle the other day. It felt terrific, like I could think clearly again. Doug”—her husband—“misses them. But he’ll live.” Maureen’s son has grown and left home, and she’s all right with that. Recently she told me she cleared out his childhood room, lugged the last of his gear to the Salvation Army. Don’t get me wrong: she treasures her boy—man, now—but he’s moved in with his partner and she’s ready to return to her comfortable vacuum.

I don’t get it. How can anyone breathe in such nullity? As an infant thrives on human touch, I need my collections encroaching into my space. Without them grounding me, I fear I’d float into the echoing night sky.

I tell Maureen, “Add billowing white curtains to the windows of your house and that’s how I picture death. A vacant expanse with nothing to grip onto. No offense,” I tack on.

She waves her hand to tell me I can say what I like. “Yes,” she says aloud. “Doesn’t it sound perfect?”

Back when Celia lived at home, I rarely insisted she clean her bedroom. As a beloved only child and grandchild, she had a lot of stuff. I figured her space belonged to her. Sometimes I’d offer to help her organize, but she usually declined.

If she wanted to exist in chaos, that was her business. And chaos it was, with clothes and half-read books littering the floor, countless dolls or figurines (later, scrunchies and makeup and lotions) modeled in ever-changing tableaus. Each morning she emerged from her tangled nest of blankets and at night she scrabbled back into them like a small burrowing animal.

“I bought new plants and a few prints I framed and hung,” Celia, now 23, said the other day on the phone. “You should come see them, but I want to straighten up first.”

“It doesn’t matter to me.”

“I know. But David’s coming over later.”

David. The much-loved boyfriend who’s lasted months. He’s a decent guy who treats Celia well, a man my daughter seems serious about, so she needs me less than she used to (a mother can tell), which starts the hunger in my belly howling like a freight train.

“And the mess is annoying, my things scattered everywhere,” Celia goes on. “I don’t know how you managed when I was young. I would’ve tossed out half my things.”

“Really?”

Celia hesitates a beat too long. “No. That would’ve traumatized me.”

“There you go. And you turned out fine. You got good grades and worked hard. And you’re sort of neat now. Sometimes.”

“I guess.”

“Your dad and I should do another purge, though. A serious one. I don’t want you caught with our clutter one day.”

“No!” Celia is horrified. “I want your clutter. I’ll keep it forever, right next to mine. It’ll help me remember.”

Celia comes by her love of possessions honestly, since it runs in the family. My Bubby, a child of the Great Depression, saved buttons and soap bars and old linens, just in case. But other than that, she skimped on fripperies and rarely bought anything new for herself or her daughters. As a result, her descendants accumulate. My aunt’s enormous home is brimming with antiques and charming tchotchkes perched just so on her many surfaces. In her spare time, she runs a business that specializes in all things upscale and vintage, so she has an excuse to continue buying.

My mother stockpiles indiscriminately, her condo packed with purses she doesn’t carry, coats she doesn’t wear, interesting lamps that don’t work, and so on. She sells old jewelry and silverware on eBay. Like my aunt, my mother knows when to set a few items free.

As for my cousin, she collects designer clothes and accessories with desperate fervor, accumulating so much that she started a shop in her basement to unload the spillover. But when you try to buy something, she’s often loath to let it go. A pair of Coach boots, say, still in box. “Oh,” she’ll moan when you ask the cost. “I really liked those. I might wear them someday.”

“But they’re in your basement shop,” I remind her.

“Yes, but still.” She holds the box close in her arms like a small child.

I’m never getting those boots.

Then there’s me. When I cull—because I absolutely have to, because I’m flat out of room—it feels like an amputation, like I’m losing my hands. I love everything I own, even if it doesn’t satisfy me.

I want more. Gimme gimme. Because I’m not just hungry for food these days.

I wasn’t always like this. When Celia was a newborn, I didn’t know what to do with the squalling creature in my arms. It took months to treat my postpartum depression, which emptied me like a sieve, but when I beat it back (better living through chemistry!), when I got to know my daughter, everything changed. Even as I funneled my life force into Celia, her presence healed the chasm inside me like a long-lost friend come home.

Yes. Yes, it’s you. I missed you so much.

As she grew, she required more energy from me, and that was fine. I had plenty to spare. Never mind that I quit writing for a decade—because who had the time? It didn’t matter. I was replete and didn’t need another morsel.

Understand, I’m not some innate earth mother. I don’t care about other people’s kids. I don’t brighten when a rosy-cheeked infant coos like a lovebird or a toddler wobbles in a charming manner. They’re all fine, I suppose. But they’re not Celia.

From babyhood through her teen years, Celia became my plus-one, poor Steven often relegated to also-ran. Even when my girl went to college (agony!), our connection didn’t fade because she still needed me—for when she had mono or Covid and I delivered meals and medicine. For when I soothed her on the phone. For those heartbreak-times. I mattered.

But that was before David.

It’s a new year. The big spending holidays have passed, though they felt shorter than usual and bittersweet this time around.

Way back when, my Bubby died on a Christmas day. After that, I didn’t have a good December until Celia arrived well over a decade later. For our girl, Steven and I observed everything in a wild frenzy—Budquanzahannukahmas, Steven called it in a single breath. But mostly we celebrated our own dumb luck at having found each other, at being exactly the family we were. We brought out Hannukah lights, a Santa hat for the large ceramic Buddha, wreaths and snow globes and multiple menorahs. We dragged the put-upon Norfolk Island pine from its sunny spot by the window and decorated it to an inch of its life. The largess of it all was embarrassing, but, oh well.

During these festivities I felt especially sated. I rarely overate, nor was I desperate to fill the rooms of my house with more stuff. Despite the excess all around—the too-many gifts, the gold-wrapped chocolate coins cramming our stockings, the floor littered in a Technicolor snowstorm of wrappings—despite it all, I had achieved balance. I was complete, a jigsaw puzzle made whole.

I thought it would last forever.

Dream on.

This past year, Celia spent the run-up to the holidays with David, part of it in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, with his family, so I didn’t bother with much decorating. The missing luster in our front rooms echoed the hollow inside me, and even as I write this, I’m imagining the treats hidden in our kitchen cupboard (though I’m out of luck because I don’t buy those anymore. Steven might enjoy some more goodies, but he’ll deal with it).

Celia still came home, and for the days she gave us, I felt full again, suffused with gratitude, if only for a little while. Then she packed up and returned to her busy schedule. It’s what she’s meant to do. It means I did all right as a mother. I brought her into the world, then I let her create her own.

And really, I’m (mostly) okay with that.

Who knows what’s coming in the years ahead because David has asked Celia to move with him to New Orleans after she finishes nursing school. She’s torn, being so close with her father and me, but she’s considering it.

Louisiana. Hours from by plane from our home in Detroit. A land without seasons, drenched with sweat and palm-size palmetto bugs that roost in trees like birds. I know New Orleans is said to be charming beyond compare, a place where a bad meal doesn’t exist, but I can’t fathom the distance—Celia so far from us, unable to swing home on a whim, to spend the night bundled in her childhood bed, the two of us sharing chocolate and secrets. The thought of her going away makes the perpetual whine in my belly shriek like a horror film heroine. I fear it might be me.

When she told me the news, I didn’t groan aloud or fold up like an old metal chair. I didn’t tear my clothes and beg her, Please, please don’t leave me, because that’s not what good mothers are supposed to do. But I wanted to.

“Are you breathing?” asks Tanya, my therapist-cheerleader when I come to her to process this debacle.

I shake my head, suck in a gasp of air, and whimper. Tanya smiles like I’ve just accomplished something marvelous.

“Just don’t get ahead of yourself, all right?” she says.

In other words, don’t succumb to the terror-fueled appetite clawing me down the middle (and good luck with that). “Try not to panic before anything’s settled,” Tanya continues. “And worst-case scenario, even if Celia leaves, there’s nothing to stop her from returning in a few years. Don’t underestimate the bond your daughter has with you.”

Years? I go on fretting (and whimpering).

It’s only later when the realization comes to me, bringing with it the smallest measure of consolation. I’m at the kitchen counter making a sandwich (low-carb bread, hummus, and lettuce) when the insight slashes fast across my brain—that my Celia can leave, that she’s capable of doing so, both in body and spirit. Despite my dismay at losing her, it’s what I always hoped for my girl. That she be competent and brave, able to give and accept love, to move softly through the world without clutching my hand every step of the way—

But I liked it when she held my hand—

Isn’t this what all parents, even the terribly hungry ones, dream for their adult children? It’s a blessing, really (I’ll repeat it till I believe it).

I grasp the thought in my mental arms. I cradle it tight to my chest and remind myself that if my girl leaves, my breathing won’t shudder and quit forever. I won’t wither like a dying rose or fly off the edge of the planet—a lost moon drifting aimless around a too-crowded earth.

My heart will go on beating, even as it does so from far—far too far—away.