Strength and Conditioning

Whether teaching history in the segregated South or winning Super Bowls as an NFL coach, Johnny Parker has encouraged his charges to strive for a

One Friday evening in October 1975, I found myself standing on the sideline at a Mississippi high school football game alongside a former coach of mine named Johnny Parker. I was in my first year as a scholarship football player at Delta State University, Parker in his first season as the head coach at Tunica Academy. He had called me the day before and asked if I could drive up to Tunica, about 75 miles away, and “help out” during a pivotal game against North Sunflower Academy. Prior to kickoff, he led me into the locker room and introduced me to his team, telling the players that though I wasn’t born with a lot of natural ability, I had worked hard in the weight room, gotten stronger, developed good technique, and always played to the final whistle. As a result, he said, football had earned me a college education I otherwise might not have been able to afford.

At the time, Parker’s team had a record of four wins and three losses. The three losses, I suspected, must have all but killed him. A couple of years earlier, when he was serving as strength coach and defensive coordinator at Indianola Academy, where I was his starting left defensive tackle, we had won a championship at the end of an undefeated season. Over the two years that I played for him, our record was 20 wins and one loss. Parker once told us that the problem with baseball as a sport was that it required you to learn to live with defeat (even reasonably good hitters fail at their task 70 percent of the time), and losing was something Parker seemed to regard as worse even than death.

After we won that championship, the legendary University of Alabama coach Paul “Bear” Bryant offered Parker a position on his staff as a graduate assistant. But before he could pack up and head for Tuscaloosa, he received another offer, to run the strength and conditioning program for head football coach Paul Dietzel at the University of South Carolina. He accepted that job, but after only a few games, Dietzel announced his resignation, effective at the end of the season. Unwilling to work for the new head coach, and unable to immediately land another job at the university level, Parker returned to Mississippi.

That evening in Tunica, he handed me a clipboard and asked me to diagram the opponent’s blocking schemes after each offensive play. This would have been a difficult enough task if I’d been in the press box, with an aerial view of the action. From the sideline, it was impossible, leading me to suspect the real reason he wanted me there. He must have known that I had quickly fallen out of favor with the Delta State coaching staff and was serving as nothing more than scout-team fodder. He had always thought I might make a good coach myself and was probably trying to give me some on-the-job training. He did things like that. The previous spring, after the job at South Carolina played out, he’d insisted I meet him three afternoons a week at Indianola’s Legion Field so that he could conduct the personal conditioning program he had devised for me; he had heard rumors, unfortunately true, that I’d been enjoying too many senior parties and putting on the wrong kind of weight. He was staying at his mother’s home in Shaw, which meant he had to drive 20 miles each way for the unremunerated job of helping me overcome my worst impulses. The gate to the field was always locked, so we climbed over the fence and he ran me to the point of exhaustion. On one of those long afternoons, he told me that he couldn’t imagine what would become of me if I ever lost football. I couldn’t either.

My efforts in Tunica, along with his own and those of his assistant coaches, were not rewarded. North Sunflower won 27–0. Never one to hide his displeasure when players performed poorly, Parker did a lot of yelling as the game slipped away, and on the sideline one of his offensive linemen broke into tears. The bleachers were right behind the home team’s bench, and by the end of the contest, the coach was not the only one yelling. The fans seemed at least as unhappy with him as with the final score. One of them bellowed, “We’re gonna send you packing, Parker!” Driving back to my dorm after the rout, I felt awful for him. A short time before, he’d been on the way up. Now he was clearly headed in the opposite direction. Tunica went on to lose the remainder of its games, and when the season ended, Parker resigned.

Refusal to accept defeat, I have learned, is not always the sign of a sore loser. A little more than a decade after that dismal evening in Tunica, I sat in front of my television watching Johnny Parker—who was then the New York Giants’ strength and conditioning coach—celebrate on the sideline with other members of Coach Bill Parcells’s staff and All-Pro players Lawrence Taylor, Phil Simms, and Leonard Marshall. The Giants had just defeated John Elway and the Denver Broncos in Super Bowl XXI. In the weight room, Parker had laid the foundation for their success.

In the fall of 1971, when I showed up in Parker’s ninth-grade Mississippi history class, he was 24 and had been an instructor and assistant coach at Indianola Academy for two years. It is important to know that in the Mississippi of that era, and some other southern states too, the word academy was code for an all-white private school established by the Citizens’ Council (sometimes referred to as “the white-collar Klan”). The sole purpose of these schools was to maintain segregation in defiance of the landmark 1954 U.S. Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education, which ruled “separate but equal” school systems unconstitutional. The only Black people at our school were members of the janitorial staff. Some of our teachers spouted racial slurs in the classroom. Parker, though very much the product of a deeply racist society (just as I was), never did that himself. His saving grace might have been his father, a Methodist pastor in Shaw who, before embarking on his ministerial career, had earned a doctorate in history, with a concentration in the classical period.

“I’m sure you remember how, back in the ’50s and ’60s, Black people would step off the sidewalk into the street when white people walked toward them,” Parker recently said from his home in Florida, where he has lived since retiring at the end of the 2007 NFL season. (Over the years, we have kept in touch, often engaging in lively, hour-long phone calls.) “That always bothered my father. He knew it was wrong. He didn’t have the power to stop it, but what he started doing when that happened was to step off the sidewalk himself and walk even further into the street than they had.”

Like every other teacher in the state, whether employed at a segregation academy or a public school, Parker was required to use a textbook by the Mississippi State University history professor John K. Bettersworth. Here’s a representative passage from the 1959 edition dealing with the antebellum period:

Mississippians who had once talked of slavery as a necessary evil began to adopt the view that it was not necessarily a wrong. In part this changed attitude resulted from the ever more insistent attacks of the Abolitionists, who forced Mississippians to defend themselves in any way they could. As a result, the many good features of slavery were henceforth enlarged upon, and its bad features were played down.

The most overtly racist passages had been excised from the updated 1964 text that Parker used, but the book still presented a Mississippi in which Black people and white people got along in sweet accord, the only conflict fomented by outside agitators. The murders of NAACP leader Medgar Evers, in 1963, and voting rights activists James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, in 1964, are glossed over in a single sentence. The 1955 murder of Emmett Till, which had taken place about 30 miles from Indianola, is not mentioned in either edition of Bettersworth’s text. Parker, who surely knew about it, did not choose to enlighten us, and I did not learn about it until I entered graduate school. Not an auspicious beginning for a man who would coach in four Super Bowls, winning three of them, in a league in which, for much of his career, the majority of his players were Black. Not an auspicious beginning, either, for a novelist and college professor like me, whose entire career has been spent teaching in a multicultural environment.

Six-foot-three, 205 pounds, with blond hair, blue eyes, craggy facial features, and rippling biceps, Parker was an imposing figure, around whom a certain mythology had already sprung up by the time he arrived at Indianola Academy. He had been known to throw erasers at boys who drifted off during his lectures and kick over the trashcan after receiving several wrong answers in a row. According to another story, after finally losing patience with a student who sat in the back row—a girl who had a soft voice and always gave nearly inaudible answers when called upon—he strode to the back of the room, picked up her desk with her still in it, carried it to the front of the room, placed the desk—and her—atop his own desk and made her stay there for the rest of the period. Most of us were terrified of him.

The first day of class, with confidence bordering on arrogance, Parker told us that he was going to make sure we kept our eyes “on the big picture.” The big picture, he said, was the maximization of our own potential, which meant that every day we must devote ourselves wholeheartedly to the task at hand—in this case, the study of our state’s history. “I can’t be certain that anyone else will demand this of you,” I recall his saying, “so I’m taking on the responsibility.” He warned that in his class, he would subject us to extreme pressure and that our time with him would be much more pleasant if we made up our minds to give 100 percent effort every day.

By design, he administered frequent exams that no one could finish in the allotted hour. Many of my classmates came close to finishing. I, however, never did. I did the bare minimum in class, which was generally enough to get a C-minus. Parker always slapped my graded exam down on my desk, usually shaking his head in disgust. The great exception came the day we received our scores from an intelligence test that had been administered by two enlisted Air Force men. Parker walked down each row demanding to see our results. After gazing at mine, which had placed me near the top of the chart, he said, “Yarbrough, you stink.”

I liked football, and, because I was of decent size, I was finally getting to play a little bit on the junior high team, made up of kids from the seventh, eighth, and ninth grades. But the knowledge that Parker would be my coach if I kept playing in 10th grade made me queasy.

Nevertheless, the following semester, when ninth-graders who had survived a couple of months of his notoriously demanding strength and conditioning program would be eligible to try out for the varsity team, I presented myself in the weight room. This happened more than 50 years ago, and I would be lying if I said I recall exactly why I did it, what I hoped to accomplish. Certainly, I never expected to be a first-team player, let alone win an athletic scholarship to college. I had never been very good at anything except playing rhythm guitar in an amateur country band with two grown men, and by ninth grade I already had too much musical intelligence to think I could make any kind of life out of that. I had always loved to read and from time to time indulged myself by fantasizing about writing novels, but neither of my parents had even graduated from high school, so surely nothing so grand could happen for someone like me. My football-related dreams, whatever they were, could not have been large, because as I have told Parker many times, I seldom heard anything good about myself from my father or my other teachers and found it easy to give up. I probably went to the weight room because I just didn’t know what else to do with myself. What I can say for sure is that I never dared to imagine that Johnny Parker was about to change my life, though that is exactly what happened.

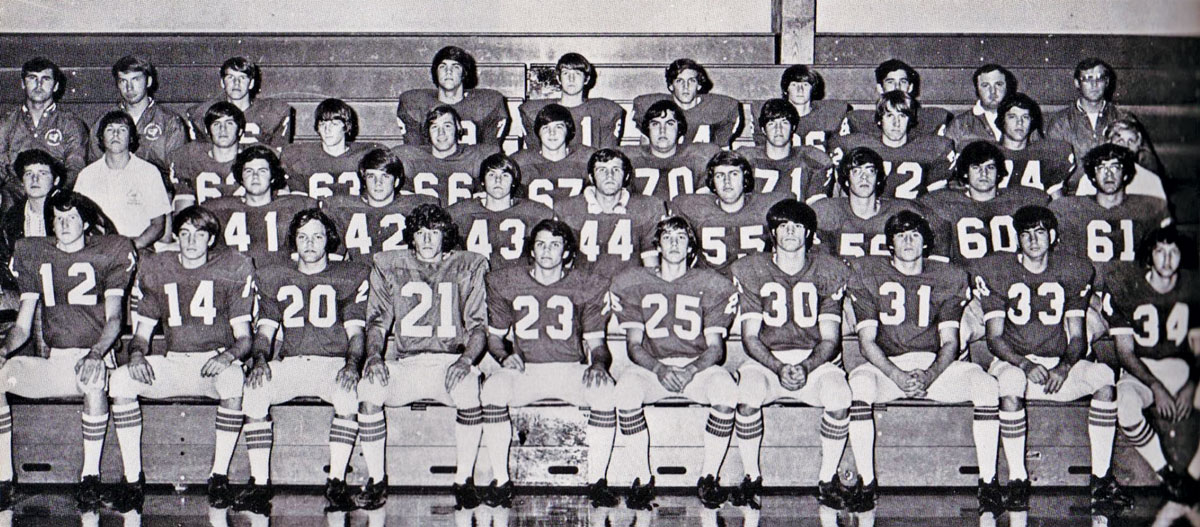

The Indianola Academy championship team from 1973. Johnny Parker is pictured in the back row, second from the left. The author, number 72, is the second player from the right, row three. (Courtesy of the author)

In a January 1987 interview with New York Times columnist Dave Anderson, conducted a couple of weeks before the Giants won Super Bowl XXI, Parker said that “when you lift weights, it’s so physically demanding, you need time between sets, you have time to visit. And then you have the unifying effect of having done tough things together that nobody saw, that nobody knows about.” The part of that quote that sticks out for me all these years later is the final line.

When spring practice started in March, I would be competing against my teammates. On the first day, I would line up opposite a rising senior named Bob Harper, in a drill aptly referred to as “the nutcracker.” In full pads and headgear, I took a three-point stance between two blocking dummies, which look similar to the heavy bags that prizefighters pummel, while Harper, who played linebacker but wasn’t even a starter, crouched before me, arms dangling, fists clenched. Behind me, a running back waited in his three-point stance while in front of him and a bit to his left, our quarterback, gripping the football he would be handing off to the running back, shouted, “Down … set … hut!” On the final sound, I launched myself at Harper, who threw his right forearm into my face, used his left arm to shuck me aside, then hit the running back head-on and drove him to the ground.

The fate of the running back did not overly trouble me. What troubled me was the blood spurting from my nose, the hot tears stinging my eyes, the head coach growling, “That looked horrible, Yarbrough!” and the shame rising inside me as I righted my helmet and slunk to the back of the line. All I wanted in that moment was to quit and go home. What prevented me was the experiences I’d had the previous two months in the weight room, where Johnny Parker and the guys I’d been cheering for on Friday nights the past couple of years—rising juniors and seniors who strutted around town in their letter jackets and got their pictures in the Enterprise-Tocsin and never acknowledged me in the hallway—were suddenly cheering for me the first time I bench-pressed more than I weighed. Before long, Parker had even coined a nickname for me—“Yarddog”—which I’ve been told had a lot more to do with my newfound tenacity than with the first syllable of my surname. To my complete amazement, for the first time in my life, I felt like I was becoming part of something special. In the weight room, the only person I had to compete against was Steve Yarbrough. And I felt sure I could conquer him. In that shabby little cinderblock space, with a multistation Universal Gym system that would be replaced a few months later by the free weights and squat rack that Parker favored, I was starting to understand that I’d been beating up on Steve Yarbrough for years. I hadn’t given the poor guy a chance.

For several months in 1972, I kept a diary of sorts, the only time in my life I have done that. It tells me that on the first day of weight training, I was 179 pounds. A little more than two months later, on the first day of spring practice, when Bob Harper temporarily turned me into his personal ragdoll, I weighed 184. On the first day of fall practice, after a summer in the weight room and a daily dose of protein powder, I weighed 195. I began the season playing on special teams and serving as the backup at left defensive tackle. By the sixth game, I weighed 198 pounds and had become a starter. By the seventh game, when I made a tackle at the goal line in the final minute to preserve a one-point win and keep us unbeaten, I was designated Player of the Week, getting my picture in the paper and a $10 gift certificate to a local men’s shop. Grown men and women who’d never spoken to me before said hello downtown.

Was everything else in my life suddenly right? Well, no. My father was still susceptible to wild mood swings and, if anything, seemed angrier at me than usual, possibly because he always had to work on Friday nights and couldn’t even come watch me play and hear the name “Yarbrough” over the stadium PA. I was still a C-minus student, I was still poorly dressed, I still had no girlfriend. Also, Parker and the other coaches criticized me mercilessly during our Monday film sessions for every missed tackle and for every time I lined up in the wrong place or jumped offside. But they criticized everyone else for their mistakes, too. At least I was one of the guys. Parker did frequently use me as an example in the weight room, pointing out how much bigger and stronger I’d become. He also went out of his way to compliment me when I made a good play.

“The thing is,” he told me not long ago, “I didn’t coach weights, and I didn’t coach defense. I coached people. Back then, I didn’t know all the things about you that I’ve learned in later years. I coached you hard—I coached everybody hard. But at a certain point, I sensed you didn’t have a real high opinion of yourself. Sometimes you needed to hear what was unique about you.”

I asked him—not unreasonably, it seemed to me—how his approach to coaching changed as he progressed from one level to another, during a career that took him from Tunica Academy to jobs at Indiana University, LSU, and Ole Miss and NFL stints with the Giants, Patriots, Buccaneers, and 49ers.

Over the phone, I heard an ominous silence. “I don’t like that word you just used,” he finally said, as if I’d dropped an F-bomb on the only coach I’ve ever known who never once swore. “There’s no such thing as levels. What’s the big picture?”

I was sitting in my living room a few miles north of Boston, a 67-year-old writer with 12 books to his credit, staring across the street at his neighbor’s maple, which looked, that crisp autumn morning, as if it might have been painted by Renoir. A telltale warmth had announced itself in my cheeks, just as it used to in the film room while one of my mistakes was replayed onscreen four or five times, prompting Parker or the head coach to dissect my failure frame by sad frame. “The big picture,” I said, “is maximization of the individual’s potential.”

His voice softened. “So who was more important to me? You or Phil Simms?”

“We were equally important.”

“You’re batting a thousand today.”

A few hours later, I recounted that conversation to Bill Parcells, the Hall of Fame coach having agreed to discuss Parker’s influence on those Giants’ Super Bowl teams. What had he seen in Parker, I asked, that persuaded him to hire a man with no NFL experience, who’d last played football himself at Shaw High School? How did he know that Parker could coach Lawrence Taylor or Phil Simms the same way he’d coached 16- and 17-year-old kids like me?

Parcells said that the Indiana basketball coach Bob Knight—whose players Parker had worked with even though his primary responsibility during his time in Bloomington was football—had called and urged him to hire Parker. Parcells had been friends with Knight for years and trusted the Indiana coach’s evaluation. Still, he remained a little leery until he interviewed Parker. “When you consider hiring somebody from Mississippi to come up and coach in New Jersey,” Parcells said, “you better make sure they can handle it. People up there tend to be pretty direct. I immediately sensed John was the man for the job. He had a lot of enthusiasm but a businesslike attitude. He believed in free weights just like I do. I’d lifted weights myself, but he knew a lot more about weight training than I did.”

Addressing the second part of my question, Parcells told me that he’d won his players’ trust ever since he’d served as the Giants’ defensive coordinator and linebackers coach, before his elevation to head coach in 1983. That he had faith in Parker predisposed them to get onboard. “The thing about professional football players,” Parcells said, “is that they need to be successful to stick around and keep doing what they do for their livelihood. If you show them you can help them achieve that goal, most of them will fall in line. The ones who won’t are a very small minority.”

One of those who didn’t fall in line, I knew, was none other than Lawrence Taylor, the fearsome linebacker whom many consider the greatest defensive player in NFL history. Prior to Super Bowl XXI, in an interview with Chris Dufresne of the Los Angeles Times, Parker mused about his mostly unsuccessful efforts to lure Taylor into the weight room. “He says ‘Oh, yeah, Johnny. I’ll lift some but you know I never know what I’m going to be doing.’ It’s hard to pin him down.” Parker went on to observe that the rest of the NFL was lucky that Taylor had so far skipped out on his program. “Imagine if the sun got one percent hotter,” he said. “It would burn up the earth. Lawrence is the sun.”

I was not the sun in the early 1970s, when I fell under Parker’s sway, and I am not the sun today. I didn’t necessarily need to succeed at football, but I longed to succeed at something, and I am convinced that if I had not met him when I did, the rest of my life would have taken a very different course. I am not the only one who feels that way.

Of the 33 players from our 1973 high school championship team, 18 received offers to play in college. The best of us was a running back named R. V. Poindexter, who went on to play for Mississippi State. Between the ages of nine and 14, Poindexter suffered a series of setbacks. First, his appendix ruptured, almost costing him his life. A few months later, his father died. Two months after that, he broke his leg, ankle, and foot, forcing him to spend half a year in a cast to his hip. Then he lost his mother to cancer. When we played together on that team, I didn’t know anything about him except that he was living with his older brother near the town of Inverness, a few miles south of Indianola. If I ever wondered why he didn’t live with his parents, I don’t recall it. Though one of our three captains, he was not loquacious. He let his performance speak for him, and since he gained nearly 1,400 yards rushing and scored 31 touchdowns, that was more than enough.

Poindexter still lives in the Delta and has had a successful career as an agricultural marketing specialist and commodities trader. When I reached him recently by phone, he told me that when he met Parker, he was mad at the world because of all that had gone wrong in his life, especially the loss of his parents. He said that some indefinable quality Parker projected convinced him to buy into his strenuous off-season training program. “Somehow,” Poindexter said, “he made me want to be part of something bigger than myself, and he persuaded me I could do it. Whenever I felt like I had nothing left to give, I could always find just a little more. That’s served me well at every stage of my life. You know how it was, Yarddog. He gave us so much of himself that we couldn’t stand the thought of disappointing him.”

Football is an undeniably militaristic endeavor. It’s about taking and defending ground. It’s also about winning and its inevitable corollary, losing. Nobody’s goal is to play for a tie. Armistices are never declared. To extend the metaphor further, the ground troops are nearly always young men, their commanders nearly always much older (though the age gap seems to be diminishing in today’s NFL). Just as few soldiers escape war unscathed, most people who play football long enough will pay a price for the rest of their lives.

Though I last donned helmet and shoulder pads in the fall of 1976—at which point I relinquished my athletic scholarship, went to work in a grocery store, and made enough money to transfer to the University of Mississippi, where I paid my own tuition and set about turning myself into a novelist with the same determination I’d discovered in the weight room—I, too, have paid that price. I first experienced the blinding pain of a prolapsed disc in my late 20s. Though I have learned to control degenerative disc disease through a combination of exercise, ice, and ibuprofen, I am always at high risk when I travel. In a couple of instances, both times while in a foreign country, I temporarily lost the ability to walk. In the final game of the 1972 season, I suffered an ankle injury that plagued me for more than four decades and eventually resulted in a ruptured Achilles, which had to be surgically repaired in 2019; the surgery led to a life-threatening blood clot. Both of my shoulders have required surgery, too, most recently last June. For a long time, the quickest way to make my wife, Ewa, apoplectic was to declare that if I had my young years to live over, I would submit to Parker’s tutelage again. Once, after one of my hour-long phone conversations with my former coach, she became exasperated enough to tell me, “I hate that man’s influence on you.”

Ewa’s attitude underwent a sea change in the spring of 2018, when she found herself face to face with Johnny Parker in a Tampa hotel. Ewa is a writer and was in Tampa to sign copies of her newly released essay collection. Initially, she’d been resistant to meeting Parker, but I’d flown to Florida specifically to see him someplace other than on a TV screen for the first time in almost 40 years, and she finally agreed to come down to the lobby with me.

Sometime in the early ’90s, Parker and I had fallen out of contact. Why that happened, neither of us is sure. He has told me that he’s never read any of my novels and never will, for fear he will see a version of himself in one of my characters and “find out what you really think of me.” As for me, there was a time in my life when, even though I thought about him on a daily basis and always appreciated his having shown me what I could do if I remained committed to my goals, I convinced myself I had outgrown him. He had taught me history, and I blamed him for all the things he hadn’t told us, beginning with the fact of Emmett Till’s murder. Also, though I had no control over it, I was and am ashamed of having attended a segregation academy; I regard the establishment of that school and others like it, many of which still exist today, as a major source of the Delta’s poverty and racial inequity. I’d become estranged from nearly everybody I’d known at Indianola Academy.

Nevertheless, in 2014, after learning that Parker was seriously ill and might not recover, I had reached out to him through the head coach of our 1973 championship team. On October 16, I received the following email:

Steve,

You have lived a life of great accomplishments, and I am

extremely proud of you.I would like to hear from you.

Johnny Parker

We had countless warm exchanges over the next couple of years but hit a rough spot in the spring of 2016. A lifelong Republican, Parker expressed initial support for Donald Trump. Eventually, he became disenchanted enough not to vote for his party’s nominee, though he told me he simply could not cast his ballot for the Democratic candidate. Immediately after the election, he saw something on my Facebook page that he responded to with a certain amount of heat, and later that night, after one too many glasses of red wine, I wrote him an accusatory email. It took us all of five minutes, somewhere around three a.m., to get past that. The more he saw of the 45th president, the more appalled he became. He would later leave the GOP and become an independent.

The day we arrived in Tampa, Parker had to be hospitalized because of congestive heart failure. He refused to tell me the name of the hospital, saying he could not bear for one of his former players to see him in such a diminished state. I asked if he could imagine, say, Vince Lombardi refusing to see former players like Jerry Kramer or Paul Hornung under similar conditions. He chuckled, then said, “Nice try, but no cigar.” He talked his way out of the hospital the following morning, though, and drove to our hotel.

The man who appeared in the lobby was a bit breathless from having walked a hundred yards or so from the garage. Suffice it to say that neither Parker nor I have the bodies that used to be ours. He has suffered multiple bouts with cancer, undergone numerous surgical procedures, several of which led to infections, and experienced other maladies that he would not want me to write about. But his blue eyes were as lively as ever that afternoon, and the only curb on his enthusiasm was an occasional stretch of labored breathing.

Naturally, we went over old times for a few moments, talking about the guys from our championship team, several of whom were no longer alive. Then, correctly thinking I might want to see what a Super Bowl ring looked like, he pulled all three of his from his pocket and laid them beside me on the couch. I picked one up, admired it, then handed it to Ewa, who graciously examined it, even though my annual Super Bowl party is not, it’s fair to say, something she eagerly anticipates. Parker quickly turned his attention to her, asking her numerous questions about growing up in Poland during the Cold War, about her father’s World War II service in the Red Army under Marshal Rokossovsky, about Lech Wałęsa and her own participation in antigovernment protests while a member of the Solidarity trade union. He told her he’d traveled to the Soviet Union in 1983 and again in 1986 to study with their Olympic weightlifters, and he’d seen how a totalitarian state operated. He said he felt tremendous admiration for her courage. As always, Johnny Parker was about winning, and it did not take him long to win over my wife.

Our time with him was short because Ewa needed to get ready for her book event. She hugged him goodbye, and I walked him out to the garage. On the way, I told him again what a great influence he’d been on me, how while my first novel was being rejected by 43 publishers, I kept hearing his voice urging me on, reminding me that he’d seen me do hard things before and he knew I could do them again. He deflected the compliment, saying it had been an honor to know and coach me when I was young. He also told me that before each of the four Super Bowls he’d coached in, he had gone out onto the field a few hours prior to kickoff, sat down on a bench, closed his eyes and thought about me and all the other players on our 1973 high school championship team. “That team’s willingness to work hard and sacrifice was my inspiration,” he said. “Y’all made me look a lot better than I really was. I owed being in the Super Bowl to you and your teammates.”

By now, I know Johnny Parker better than I could possibly have known him when I played for him. The gap between us back then was as wide as our present bond is deep. I’d rather talk to him than just about anybody except my wife and daughters. We’re in touch every day or two and have been for several years. Our discussions range widely over history, politics, travel, music, and, of course, football.

I know he means it when he says that no player is more important to him than any other. But a name that kept coming up in our conversations after I told him I was going to write this piece was that of Bryant Young, who’d been a star defensive tackle for the San Francisco 49ers, the team I followed during the 21 years I lived in California. When Young was about to be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2022, he asked Parker to be his guest at the ceremony. Parker declined the invitation. “I was not going to let Bryant Young see me in a wheelchair,” he said. But he suggested more than once that I give Young a call.

Young—who is Black and grew up in Chicago Heights, Illinois, a town of 27,000 where people of color make up about 70 percent of the population, just as they did in the Indianola, Mississippi, of my youth—told me that when Parker coached him, from 2005 to 2007, both of them were nearing the ends of their careers. He’d lifted heavier weights under Parker’s coaching those last few years, he said, than at any other point during his time in the NFL. He said he found Parker to be “a no-nonsense guy” who was nevertheless eminently fair and consistent from one day to the next. “There’s a certain way,” he said, “that he wants to live his life, and he stays true to his beliefs. That’s a fine thing to see, a memorable thing to see. Knowing where he started, how hard he had to work to get to where he was, that was really inspirational. It’s something I took away from all our years together.”

We’d no sooner said goodbye than I began to wonder why I hadn’t asked Young what he meant when he used the phrase where he started. But it wasn’t long before I realized that I didn’t need to ask because I knew where Parker started. After all, I started there too.