Six Encounters with Lincoln: A President Confronts Democracy and Its Demons by Elizabeth Brown Pryor; Viking, 496 pp., $30

When Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in April 1865, a halo of retrospective sanctity quickly gathered around him. Lincoln was hailed as the Great Emancipator, the strong-principled, humane leader who had saved the nation during its worst crisis. The glow around Lincoln has never disappeared. Historians polled over the decades since World War II have consistently put Lincoln at or near the top of American presidents.

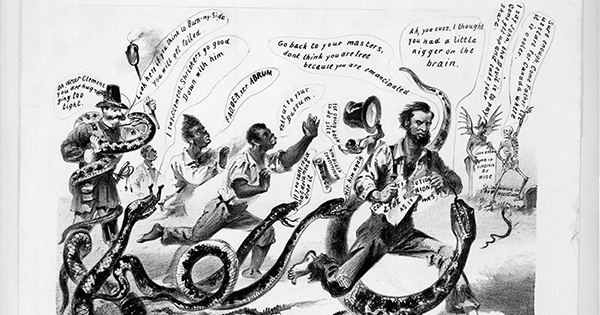

There is, however, an anti-Lincoln tradition. In Lincoln’s lifetime, proslavery Southerners rejected him, conservative Democrats disdained his antislavery stance, and Radical Republicans found him too cautious on slavery. Criticism of Lincoln has continued ever since. It has been charged that he was a crude jokester, a coldly manipulative politician, an egotist driven by overactive ambition, a tyrant who crushed civil liberties, or a racist.

All these critiques and more appear in Six Encounters with Lincoln, by the late Elizabeth Brown Pryor, an American diplomat and historian who died in a car accident in 2015. Pryor’s deeply researched book is more convincing than most others that take a predominantly negative view of the 16th president. But although Pryor provides some fresh information, a fuller contextualization of Lincoln would have created a more nuanced portrait.

The six encounters mentioned in Pryor’s title were meetings between Lincoln and individuals or groups that represent for Pryor various perceived weaknesses, including his ineptness as a military leader, his crudeness and levity, his tardiness on emancipation, his alleged racism and male chauvinism, and his lack of literary ability.

But how weak was Lincoln, really, in these areas? Pryor seems most accurate in her portrayal of Lincoln’s treatment of Native Americans. Not only was Lincoln patronizing to the natives who visited him in Washington, but he also did little to interfere with cruel actions taken against Western tribes. Pryor concludes, “By almost any measure, the Lincoln administration was catastrophic for Native Americans.” True, but Lincoln’s Indian policy was, alas, hardly new. It extended back to Jefferson, and it was carried out by virtually all other presidents, most notoriously Andrew Jackson. Lincoln’s continuation of this harsh policy was disappointing but not unsurprising in light of long-standing practices. An additional complication for Lincoln was that a few of the Western tribes owned slaves and in some cases fought for the Confederacy.

Pryor’s questioning of Lincoln on other issues strains credulity. She claims that there was little mutual respect between him and his generals, who were, she suggests, in the main unwisely chosen. His response to the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter was, she writes, “insultingly amateurish,” and “his encouragement of freelancing by men not authorized to conduct operations, hampered military effectiveness for the duration of the war.” Let’s recall, though, that the North won the war, largely due to Lincoln’s military shrewdness. He was a tyro at the start, but he endorsed attacking the enemy’s armies simultaneously in different arenas while occupying Southern locales when possible, a strategy that worked brilliantly when it was adopted by Grant and Sherman.

Pryor emphasizes that Lincoln was a shabby dresser, an inveterate teller of jokes and stories, and an indecisive man who lacked finesse. Pryor writes: “[S]uch uncertainty at the top of the hierarchical chain can infect an army, stifling nerve and zeal. For the next four years, the commander in chief would struggle to pro-

ject authority, never really understanding how spit and polish instilled confidence.” Pryor’s model of spit and polish is Robert E. Lee, with his “matinee-idol looks” and “easy, brilliant smile.” Pryor reports someone saying that “even God had to spit on his hands when he made Bob Lee.” Well, the spit-polished Bob Lee was roundly defeated in Virginia by the cigar-puffing, bibulous U. S. Grant, directed by the homely Old Abe, while the grizzled “Uncle Billy” Sherman overwhelmed other chivalrous Southern generals in Georgia.

Pryor describes Lincoln as a “reluctant emancipator,” comparing him unfavorably with Union sergeant Lucien P. Waters, an abolitionist who single-handedly spirited away slaves from the South. Pryor neglects to say that Lincoln had long been aware of such antislavery vigilantes, including John Brown, and shared their passion—so much so that he said, “I have always hated slavery, I think as much as any Abolitionist.” But he knew that individual war was futile, and it could disrupt the Union, which Lincoln was determined to preserve.

Pryor claims that Lincoln shrank from strong-minded women. She associates “Lincoln’s discomfort with accomplished women” with his awkward or impolite interaction with Harriet Beecher Stowe, Julia Ward Howe, Clara Barton, Sojourner Truth, and a few others. Actually, though, he was close to a number of women who were described by his friends as “intellectual” or “bold.” Also, Pryor misrepresents some of Lincoln’s encounters. His meeting with Stowe, which Pryor dismisses as frivolous, was actually a cordial one at which they discussed the Emancipation Proclamation. Pryor suggests that Lincoln alienated Truth with “some tactless remarks,” when in fact both parties felt the meeting was positive.

Pryor notes that Lincoln used the word nigger in front of one of his visitors. But virtually all white Americans of the time used the word, and far more often than he did. Also, several black people who knew him testified to his lack of racial prejudice. Truth said Lincoln was the least biased of any white person she had ever met. Frederick Douglass had the same response. “In all my interviews with Mr. Lincoln,” Douglass said, “I was impressed with his entire freedom from popular prejudice against the colored race.”

For Pryor, Lincoln’s advocacy of colonization—the plan to deport emancipated blacks —signaled his deep conservatism on slavery. But the removal of blacks from the country was among the most popular ideas of the era, one that many others had endorsed, including black reformers such as Martin Delany and Henry Highland Garnet, who called for the emigration of African Americans due to pervasive racial prejudice at home. When Lincoln made this argument to a black delegation in August 1862, he was most likely feigning conservativism to create a buffer against the shock he knew would come when he issued the Emancipation Proclamation. As soon as he signed the proclamation the following January, he deemphasized the colonization scheme.

Then there is Lincoln the stylist—a poor one, according to Pryor, who generalizes of his writings, “most are wooden documents, often clumsily written, unless highly polished for political purposes.” But “flexible” is a better way to describe Lincoln’s style, which is by turns terse, discursive, legalistic, and poetic. At his best, he was an unmatched stylist whose words redefined America and still inspire the world.