The Affair Rekindled

Remembering the plight of Dreyfus and the effect it had on a young Marcel Proust

In 1896, Count Robert de Montesquiou, a first-rate dandy and second-rate poet, opened a letter sent by a friend. In an urgent tone, the friend wanted to explain his silence in response to remarks Montesquiou had made the previous day. Though he does not describe the remarks, it is clear they concerned Jews and Judaism. “If I am a Catholic like my brother and father,” observed Montesquiou’s friend, “my mother, on the other side, is Jewish. You understand that this is a strong enough reason to abstain from this type of discussion.”

The letter-writer was Marcel Proust. Not yet the author of À la recherche du temps perdu, Proust was instead a bit perdu himself: a 20-something aesthete and asthmatic who, uncertain of his vocation, spent his days penning essays for literary journals and his evenings polishing bon mots at literary salons. There was certainly no financial pressure to settle on a profession. His father, Adrien Proust, was a wildly successful and widely respected medical researcher. His mother, Jeanne Weil, hailed from a wealthy family of Jewish industrialists.

Jeanne refused to convert upon marrying Adrien. Although her two sons, Marcel and Robert, were raised as Catholics, Mme Proust, though nonobservant, remained Jewish. By the end of the century, however, prominent figures in France were challenging the very possibility of being both French and Jewish. A powerful tide of anti-Semitism had risen in France, posing an existential threat not just to the republic’s Jewish community, but to the republic itself. A century has passed since Proust’s death in 1922, and it is 151 years since his birth in 1871, and yet, that period is in many important respects not unlike our own.

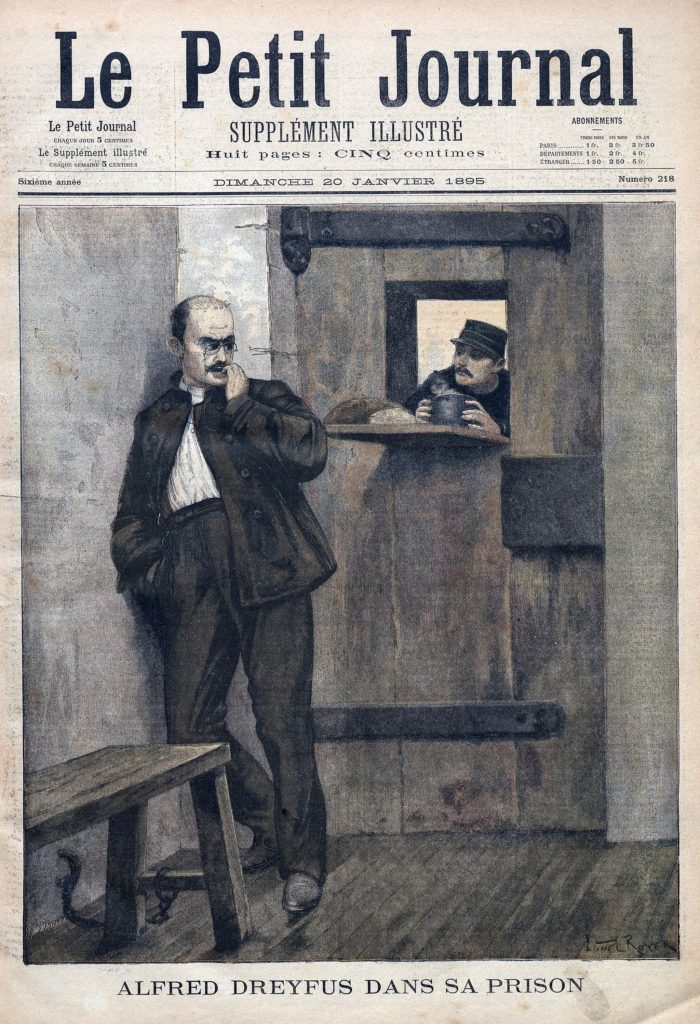

On October 15, 1894, Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a staff member of the French Army’s High Command, was ordered to report to the Ministry of War. Upon arriving there, the unsuspecting Dreyfus was accused of treason. The basis of the accusation was the infamous bordereau, a sheet of paper covered with French military plans, found by a French cleaning woman in the trash basket of the German military attaché. The hand that wrote the bordereau, the investigating officers believed, belonged to none other than Dreyfus. Any doubts they might have had were dissolved by the fact that Dreyfus was the only Jewish officer in the High Command.

Found guilty of treason by a military tribunal, the bewildered Dreyfus was sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil’s Island, a malarial rock off the coast of French Guyana. His sentencing was followed by a terrifying ritual of public humiliation. Marched into the courtyard of the École militaire, Dreyfus stood at attention while a dense crowd erupted with calls of “Death to Judas” and “Jewish traitor!” As an officer preceded to snap Dreyfus’s sword—broken and soldered back with tin the night before to make the gesture seem effortless—over the knee and tear off his insignia, Drefyus insisted on his innocence.

Two years later, as Dreyfus wasted away in solitary confinement, forgotten by most everyone except his family and friends, this appalling miscarriage of justice burgeoned into what became known as “L’Affaire.” In early 1896, Colonel Georges Picquart, the newly appointed head of military intelligence, found that another missive about French military plans had ended up in the trash basket at the German Embassy. Moreover, the writing on this newly intercepted document, which matched that of the bordereau, also matched the hand of Ferdinand Esterhazy, a dissolute and indebted officer of dubious character.

Like most of his fellow officers, Picquart was anti-Semitic. But he was also committed to the truth. When his commanding general asked him why he cared if “this Jew remains on Devil’s Island,” Picquart blurted: “Because he is innocent!” When his reply earned him a sudden transfer to a desert outpost in Tunisia, Picquart vowed that he would not “carry this secret to my grave”—he told his story in late 1896 to his friend and lawyer, Louis Leblois.

Leblois soon decided to share his information with Auguste Scheurer-Kestner, a powerful politician famed for his probity and patriotism. In late 1897, finally overcoming his caution as well as his reluctance to, in his words, “Jewify” the affair, Scheurer-Kestner revealed Picquart’s discoveries in the Paris newspaper Le Temps. The open letter sent a shock wave across Paris, carrying as far as the study of Émile Zola.

Indeed, only when Zola, France’s most respected—or, for conservatives, most reviled—writer, entered the fray did the affair became the Affair. Dreyfus’s plight ignited both Zola’s patriotic outrage and artistic excitement. This story, he wrote to his wife, represented not just a “frightful judicial error,” but also a “gripping tragedy.” Who better to tell it than the author of the remarkable Rougon-Macquart series of novels? (Or, indeed, what better time to tell the story now that he had completed the 20-book epic?)

During the last weeks of 1897, he published a series of editorials in Le Figaro—the same newspaper that would carry Proust’s chatty columns on le tout Paris—affirming Dreyfus’s innocence. Zola’s call for a new trial deepened the nation’s fracture between two violently opposed camps. On one side were the Dreyfusards who defended reason and believed that France’s identity was defined by the abstract principles of equality and liberty. On the other side were the anti-Dreyfusards who deified unreason, convinced that France’s identity was rooted in la terre et les morts—the soil and the generations of dead buried in it. For the former, objective facts attested to Dreyfus’s innocence; for the latter, subjective convictions confirmed Dreyfus’s guilt.

Not for the last time in history, in short, alternate versions of reality faced off against one another. This epistemological and ethical divide was made manifest when Zola, incensed by Esterhazy’s acquittal by a military tribunal, published “J’Accuse” in the newspaper L’Aurore on January 13, 1898. In the cadence of the Bible and with the ire of one of its prophets, Zola indicted a long list of military and political figures for sentencing an innocent man to life imprisonment while allowing the guilty party to go free. His purpose, he concluded, was “to hasten the explosion of truth and justice.”

“Explosion” was an understatement. Zola’s insistence that “la vérité est en marche, et rien ne l’arrêtera”—“Truth is on the march and nothing will stop it”—galvanized both sides. The Dreyfusards, inspired by his bravery on behalf of the truth, called him a hero; the anti-Dreyfusards, outraged by his effrontery toward the army, called for his head. Within days thousands of anti-Dreyfusards, led by the street thugs of the Ligue antisémitique, chanting “Down with Zola” and “Death to the Jews,” battled the police and ransacked businesses in the Jewish quarter of Le Marais.

Rather than taking to the streets, the Dreyfusards followed Zola’s example and took to the press, publishing a series of manifestos. Just one day after L’Aurore published “J’Accuse,” the paper carried the “Petition of Intellectuals,” which echoed Zola’s call for a new trial. The word intellectual was new to most readers, as were the names of most of the intellectuals who signed the manifesto, including that of Marcel Proust.

“I was the first Dreyfusard,” Proust boasted later in life. His claim is thin on substance—resting on nothing more than having persuaded the writer Anatole France to sign the petition—but thick with significance. The Affair was a seismic event not just for France—the nation, not the novelist—but also for Proust. Benjamin Taylor, a recent biographer of Proust, notes that the writer became a Dreyfusard upon the publication of Scheurer-Kestner’s letter. But, Taylor adds, this was not because Proust felt Jewish. Instead, he “saw himself as what he was: the non-Jewish son of a Jewish mother.” It was Proust’s indignation over this “clear-cut miscarriage of justice” that alone explains his Dreyfusard conversion.

This claim makes much sense, but does it make full sense of either the man or his times? Doubts rise from two remarkable events framing this year of Proustian anniversaries: the publication of Antoine Compagnon’s book, Marcel Proust du côté juif (Marcel Proust’s Jewish Side), and an exhibit, “Marcel Proust. Du côté de la mère” (Marcel Proust: The Mother’s Side), at Paris’s Museum of Jewish Art and History. (Compagon served as an adviser for the exhibit.) Both reveal a side to Proust mirrored, in In Search of Lost Time, by the narrator’s mocking aside, apropos society Jews, “who believe themselves free from their race.”

As readers of Proust’s epic know, this is not the case for its tragic hero, Charles Swann. In a stunning elegy for the dying Swann, who finds that the Dreyfus Affair has, despite his intellectual and cultural refinement, made him Jewish, not French, in the eyes of his Gentile peers, the narrator writes: “Swann belonged to that stout Jewish race, in whose vital energy, its resistance to death, its individual members seem to share. Stricken severally by their own [traumas], as it is stricken by persecution, they continue indefinitely to struggle against terrible agonies which may be prolonged beyond every possible limit.”

Just like Swann, Proust never escaped—or for that matter, sought to escape—his Jewish inheritance. Though he abandoned Catholicism as a teen, his attachment to his mother’s religion remained fast. Proust attended several funerals for members of the Weil clan, including, most traumatically, his mother’s service in 1905, where a rabbi pronounced the kaddish. He evokes this inheritance when he alludes to his own mortality in a haunting draft of a letter to his friend Daniel Halévy: “There is no longer anyone, not even me, unable to leave bed, to visit the small Jewish cemetery on the rue du Repos, where my grandfather, obeying a ritual he did not understand, set a stone on his parents’ grave every year.”

Strikingly, when In Search of Time Lost (and its author’s life) came to completion, a young generation of French Jewish intellectuals set a very different stone on Proust’s achievement by claiming him as one of their own. During the interwar period, as both the Compagnon book and museum exhibit reveal, influential literary figures such as André Spire, who embraced Zionism, cited Proust’s epic as a reminder that French Jews could never become fully French. (In a paradoxical fashion, the subsequent events during the German occupation of France, when more than 70,000 French and foreign Jews were murdered in the Nazi death camps, both confirm and contest Spire’s warning.)

It is doubtful that Proust would have agreed with Spire’s assertion. Far less doubtful is the notion, embodied by Proust, that being French does not mean one can also be Jewish (or, for that matter, Muslim). The point for Proust—the point, perhaps, to Proust—is the importance of being fully open to the play of past and present in one’s life. And to continue to place stones even when you no longer know why the reason why.