The Birth of the Egghead Paperback

How one very young man changed the course of publishing and intellectual life in America

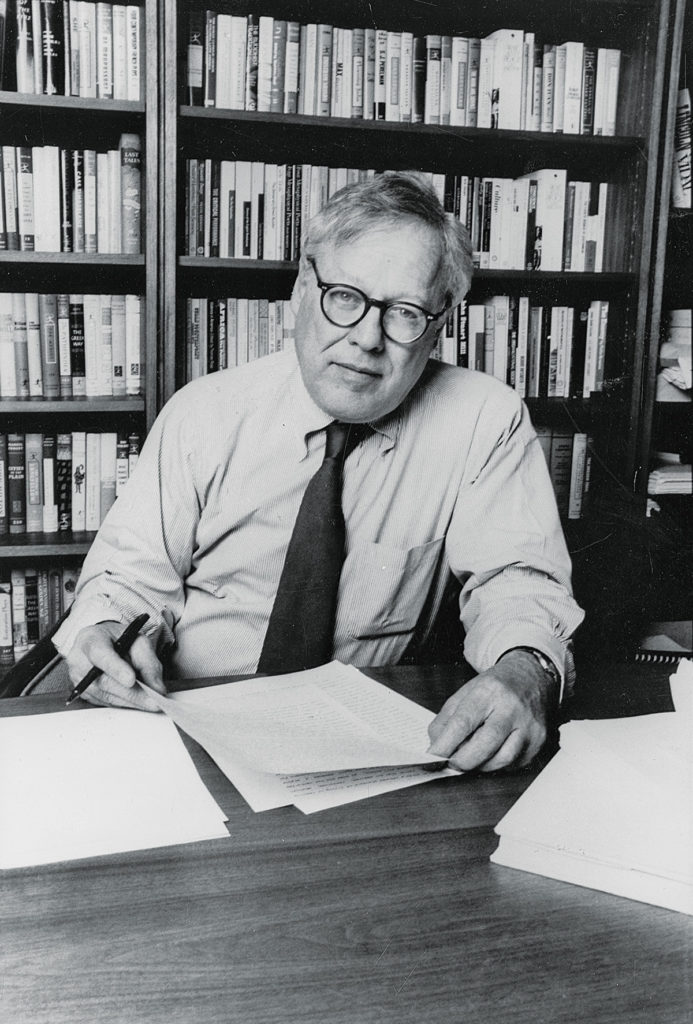

One day in the early 1950s, an editorial assistant at Doubleday was walking across Central Park with his boss when he asked whether the company couldn’t publish quality paperbacks to sell in bookstores. The young man, named Jason Epstein, had an idea for a new line of sturdy, affordable editions of “books of permanent value” in literature, history, religion, philosophy, and the arts, and he was confident that bookstore patrons would go for them.

“Wouldn’t it make more sense,” Epstein asked, “to sell twenty copies of The Sound and the Fury at a dollar than one hardcover copy at ten dollars?” His boss liked the idea.

“I had been working at Doubleday as a trainee,” Epstein, who died in February, wrote to me in an email in 2018, “when it occurred to me that my classmates at Columbia on the G.I. Bill and others like them who could not afford hard-covered editions would welcome inexpensive paperbacks of their required texts. I mentioned this opportunity to our chief editor, himself a veteran, and he said go ahead. So I did.”

Launched in April 1953 with a list of 12 titles in attractive covers and boosted by clever marketing, Anchor Books, the result of the plan, quickly found an avid readership. It also had a profound effect on book publishing, higher education, and the world of ideas in America and beyond. Its positive repercussions are still being felt today.

With the founding of Anchor Books, publishing in America would never be the same again. Although it didn’t take long for Anchor’s innovations to be appreciated by readers—and its profitability to be noticed and imitated by other publishers—its once-revolutionary approach and its cultural legacy have come to be taken for granted, forgotten, or in this digital age, largely dismissed as a vestige of “dead trees” print culture. But there was a time when an Anchor book was, so to speak, “the most interesting person in the room.”

Epstein’s idea for quality paperbacks was simple: buy the rights (at low cost) for out-of-print hardcover classics and scholarly works of likely appeal to students and educated general readers—about 10 to 15 percent of the book-buying public, and a dependably steady customer base—and then republish them in affordable paperbound editions. Print them on durable paper with attractive cover designs and sell them in bookstores. If well chosen, the titles could sell respectably (or better) year after year in the backlist. As he would later remember:

When I became a publisher it was my undergraduate encounter with books that I wanted to share with the world. I believed and still do that the democratic ideal is a permanent and inconclusive Socratic seminar in which we all learn from one another. The publisher’s job is to supply the necessary readings. But in 1951, publishers were not performing this function well, and Anchor Books seemed to me an obvious corrective.

Epstein wanted authoritative editions on topics of perennial interest to students—the book to read if you’re interested in theater, say, or sociology, or Zen Buddhism—and accessible enough for college course adoptions year after year. Then Anchor would give booksellers a

40 percent trade discount, twice the cut that newsstands were offered for pulp paperbacks. At the time, most pocket books, as mass-market paperbacks were also known, were sold in drugstores and on newsstands and handled by magazine distributors. Epstein’s focus on selling through bookstores was a significant turning point: go to where your most appreciative audience is, with high-quality editions they can afford.

As Epstein recounts in his memoir, Book Business, after graduating from Columbia College in the class of ’49 and earning an MA the following year, almost every day after work he would visit the Eighth Street Bookstore near his apartment in Greenwich Village. The store, he wrote, was “a bibliographer’s paradise and an informal school for many fledgling publishers.” He spent hours among the shelves richly stocked with hardcover editions of Dostoyevsky, Melville, Yeats, and other classics. In those days you could easily buy a Mickey Spillane or Agatha Christie novel for a quarter at the corner drugstore, but try finding Proust or Woolf or Faulkner in paperback anywhere. It occurred to Epstein, and he suggested to the store’s owners, Eli and Ted Wilentz, that if offered in affordable paperback editions, such classic works would be popular with hungry young readers like himself. The Wilentz brothers agreed.

On that February afternoon in Central Park, Doubleday editor-in-chief Ken McCormick suggested that Epstein talk to the sales and production people. Doubleday’s production manager, Harry Downey, helped Epstein draw up a business plan, guiding him through the dollars-and-cents practicalities of determining the point at which a book breaks even. He must factor in the costs of paper, printing, binding, advertising, and authors’ royalties (or the purchase of reprint rights), and then subtract these from a title’s net revenues. They would need to sell about 20,000 copies of each title to begin making a profit.

The new imprint was called Anchor Books after one of the elements of the well-known dolphin-and-anchor colophon long used by Doubleday (an image originally designed by Venetian printer Aldus Manutius around 1500). The anchor, Epstein explained in a lecture at the Morgan Library in 1995, stands for depth or seriousness, while the dolphin represents playfulness: gravitas and levitas.

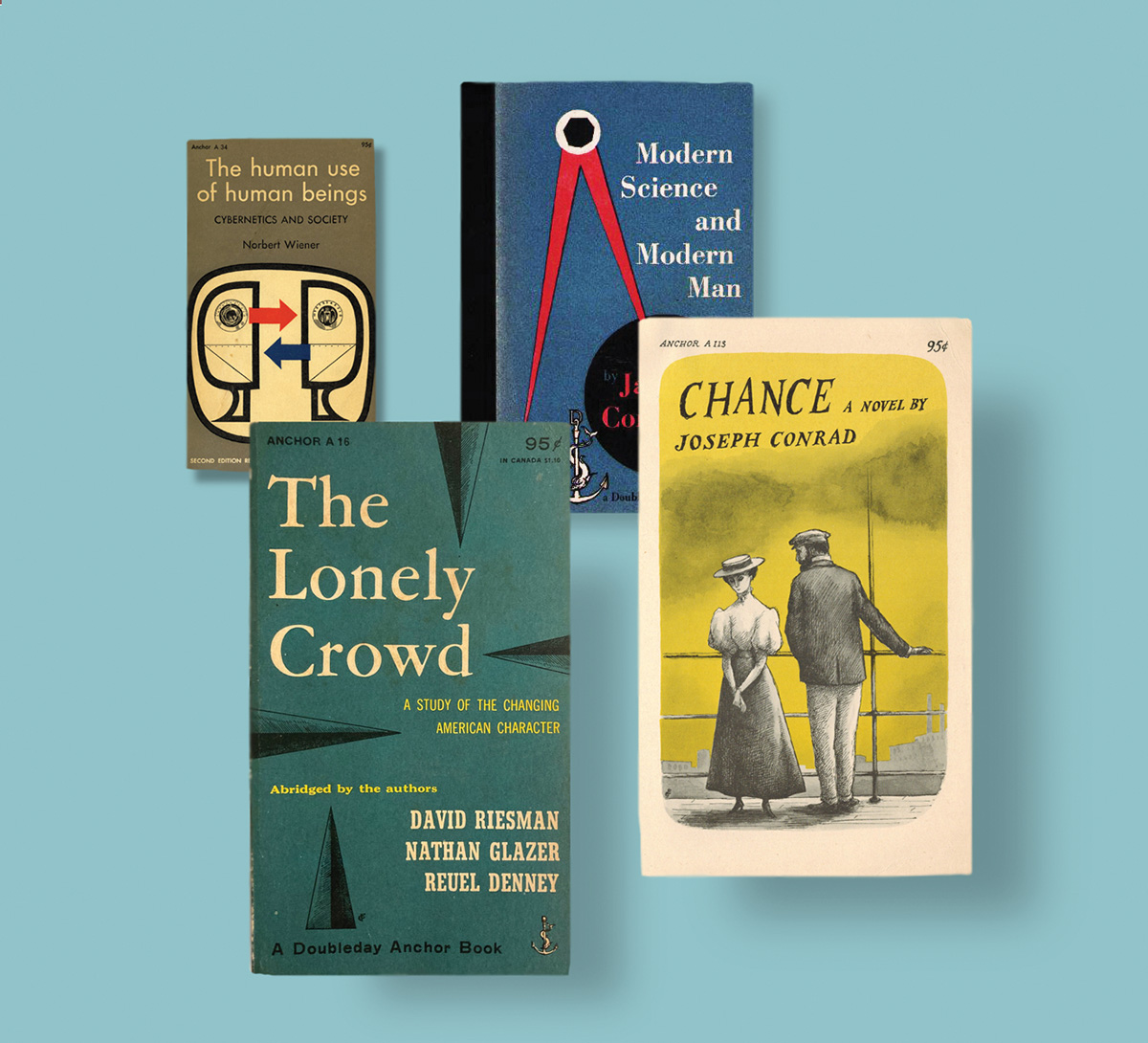

When Anchor Books debuted, the first dozen titles, bearing the tagline “For the Permanent Library of the Serious Reader,” were priced at 65 cents to $1.25 (or about $6.25 to $12 in today’s dollars). That first list was a mix of classic and contemporary, including novels by Joseph Conrad and André Gide and nonfiction by D. H. Lawrence and Edmund Wilson. The list would grow to include well-established classics from around the world, new works, and important but lesser-known titles that had gone out of print—books that were too good to let sink into oblivion.

Anchor’s first four titles sold 10,000 copies each within two weeks, according to publishing historian John Tebbel in Between Covers. By January 1955, not quite two years after its launch, Anchor had 43 titles in print and had sold 1.35 million copies. But Anchor’s success was not only in the numbers.

Hugh Van Dusen, an editor of Harper Torchbooks from that quality paperback line’s inception in 1956 until his retirement from HarperCollins in 2016, was a freshman in 1953 when he saw a display of brand-new, well-designed Anchor Books at the Harvard Coop in Harvard Square and then in bookstores all over Cambridge, face-up on a table in the front of the store. It is hard to imagine now, but at that time bookstore patrons were not accustomed to seeing paperbacks shown as premium merchandise. The display had an electrifying effect on him: “Anchor Books is the reason I went into publishing.”

The smart, clean packaging of the books had the aesthetic appeal of Apple products today. Each title was newly typeset and printed on bright, crisp paper. “I decided to print Anchor titles,” Epstein recalls in Book Business, “on a more expensive and durable acid-free sheet that retained its whiteness somewhat longer [than pulp, mass-market paperbacks] and print the covers on heavy stock in a matte finish.” (Indeed, the pages of Anchors printed in the ’50s still look fresh.) One of the first cover designers was the writer and artist Edward Gorey, who would serve as an art director for Anchor from 1953 to 1960—roughly the period when Anchor’s first 200 titles were published.

Geoffrey O’Brien, an author and former editor-in-chief of Library of America, says Epstein “thought in terms of marketing, opening up a new realm. Introductory studies for whole fields of study: this is the book you should read to get started on this subject.” H. D. F. Kitto’s Greek Tragedy, for example, or Eric Bentley’s anthology of modern drama. “The choices were so intelligent, and they had a very refined sense of the readers they were going after.”

Soon, instead of hanging out at the Eighth Street Bookstore, Epstein was visiting the subsidiary rights departments of Alfred A. Knopf and other publishers and poring through their catalogues, mining their backlists and buying paperback rights. Katherine Hourigan, now managing editor of Knopf Doubleday, who has been with Knopf since 1963, heard that Alfred Knopf himself noticed that this young man from Doubleday kept coming over and buying paperback rights for old or out-of-print Knopf titles. Hourigan recalls that Knopf wondered, “What’s going on here? What are we doing, selling these rights? We should be doing this ourselves.”

“The success of Anchor Books astounded the industry,” writes John Tebbel in Between Covers. “They became as much of a landmark in reprint publishing as the Modern Library had been in the thirties, and the list was distinguished.” Anchor’s achievement soon inspired the founding of Vintage Books at Alfred A. Knopf, Torchbooks at Harper & Brothers, Meridian Books at the Noonday Press, and other quality paperback lines, many of which are still going strong today. It also led to such distinguished trade paperback lines as Penguin’s Contemporary American Fiction and Vintage Contemporaries in the 1980s and New York Review Books in the 2000s.

The smart packaging of Anchor Books in the 1950s had the aesthetic appeal of Apple products today. (Photo-illustration by David Herbick)

Paperback publishing as we know it in the United States began in the late 1930s and early ’40s. Priced at 25 cents (roughly $4.50 in today’s dollars), mass-market titles—mysteries, romances, westerns—were printed on pulp paper and sold in train and bus stations as well as drugstores and on newsstands. Pocket Books, Avon Books, Popular Library, Dell, Bantam, and New American Library were among the most successful. In 1950, Pocket Books was the industry leader, with sales of 50 million books; Bantam was next, with 38 million; New American Library came in third, selling 30 million. By comparison, in 1950 hardcover books were sold at about $3 to $5 each, and the average total sale per title of trade books was 6,500 copies.

In Two-Bit Culture: The Paperbacking of America, Kenneth C. Davis observes that none of the pulp publishers “showed any inclination toward improving the intellectual atmosphere in America’s heartland.” Davis finds that despite helping to create a paperback readership, Pocket Books “had not always given that readership what it wanted. Anchor and Vintage quickly maneuvered to fill that void.”

Vintage Books was launched in 1954 to keep in print (and increase the profits from) the backlist, and Alfred A. “Pat” Knopf Jr. was in charge. At first, Vintage—so named, says Davis, because Alfred A. Knopf was “a great oenophile, and these books were the best from his ‘private stock’ ”—were drawn exclusively from the Knopf backlist, but after Random House’s purchase of Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., in 1960, Random House titles began to augment the list. Early Vintage authors included Paul Goodman, Richard Hofstadter, and Albert Camus.

Gary Fisketjon, a former fiction editor at Knopf and before that an editorial assistant to Epstein and managing editor of Vintage, recalls, “I was always partial to Vintage. … Since I’d been educated with ‘egghead paperbacks,’ I arrived in publishing convinced this was an essential format, cheaper editions that seemed nearly as good as hardcovers and, unlike mass-market paperbacks, were meant to last. Like many great ideas, this one was obvious from the start, in my view.”

Harper Torchbooks, begun in 1956, originally published religious works but quickly expanded into history, philosophy, sociology, and political science. Beacon Paperbacks, established in 1955, also built a strong scholarly and literary list, with works by Albert Schweitzer, Gandhi, the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., Gertrude Stein, and James Baldwin.

Another worthy line that was not often found in bookstores—or in the histories of paperbacks—was Hayward Cirker’s Dover Books, founded in 1941 as a paperback reprint house and sold mainly by mail order. Dover offered books on, among other topics, “physics, dollhouses, military history, classical music, fairy tales, 19th-century novels, cinema, [and] ancient Egypt,” according to Tom Reiss in The New York Times Book Review.

In January 1955, less than two years after its founding, Anchor Books was honored with the Carey-Thomas Award for creative publishing, the only paperback house to have won the honor at that time. In his acceptance speech, Doubleday President Douglas Black emphasized that “the editorial conception, the study and plan of publication, the market research, the organization and execution of the whole matter are Jason Epstein’s.”

A few months earlier, in a clear sign of the imprint’s growing cultural influence, one of Anchor’s authors was featured on the September 27 cover of Time magazine: social scientist David Riesman, principal author of The Lonely Crowd, a book originally published in hardcover by Yale University Press in 1950, with decent sales, but which as an Anchor paperback had already sold some 60,000 copies by late 1954.

The paperback revolution’s impact was evident in purchases for academic course adoptions, too: a seasonal surge in sales for each semester’s reading lists was seen in the publishers’ sales reports. Many of the titles had been specifically recommended by professors who remembered certain out-of-print gems that should be kept alive for new generations.

Anchor’s paperback editions brought some books to a wider public attention than they had ever enjoyed before. For example, only after its publication of Johan Huizinga’s The Waning of the Middle Ages (1954) did the book really begin to sell. Van Dusen recalls that The Waning had formerly been available only in hardcover as an import from London. “The Anchor edition was assigned in a social sciences course I took. … It remains to this day, all these years later, my favorite book. I never would have read it if Anchor hadn’t made it available. And, at that time, no other paperback line would have dreamt of publishing it. The paperback reprints made those courses richer because those editions were available. They changed the way many courses could be taught.”

In 1958, Jason Epstein left Doubleday for Random House, where by 1962 he was a vice president. He would help develop Vintage’s list; manage the venerable Modern Library (established in 1917), whose core audience he saw as similar to Anchor’s; and for the next four decades at Random House edit the works of W. H. Auden, Norman Mailer, Philip Roth, E. L. Doctorow, Jane Jacobs, Elaine Pagels, and other eminent writers. During the New York newspaper strike of 1963, he and his wife, Barbara Epstein, and friends Robert Silvers, Elizabeth Hardwick, and Robert Lowell cofounded The New York Review of Books, and in the early 1980s, he carried out the late, legendary critic Edmund Wilson’s vision of establishing Library of America, an elegant series of classics (mostly in hardcover) modeled on France’s Pléiade editions of national literary treasures.

Epstein’s Library of America colleague Geoffrey O’Brien makes the interesting observation that there was a kind of validating imprimatur about a book as designed and presented by Anchor Books: because Anchor published these books, they and their subjects entered the public discourse, “the marketplace of ideas.” In this way, Epstein’s imprint lived up to the gravitas signified by the anchor from the old Doubleday colophon.

“The list of books that Anchor assembled in its first few years of existence was astonishing in its breadth and quality,” says former executive editor of Doubleday Gerald Howard, “taken all together a shining artifact of the high intellectual culture we once had in the ’50s. For my generation of college students, the so-called egghead paperbacks that Anchor initiated were avatars of serious thought and culture.”