Four years ago, I bought myself a paperback atlas—a floppy, glossy, 200-page edition quite unlike the hardback tome that had gathered dust on my shelf for decades. And this flimsy new atlas soon altered my grasp of reality in a way so elemental that I realized I’d obtained an essential tool of knowledge and power, all for a modest $14.95. For when I found it in my local bookshop, I vowed from that day on to look up every place I encountered in my reading, no matter what.

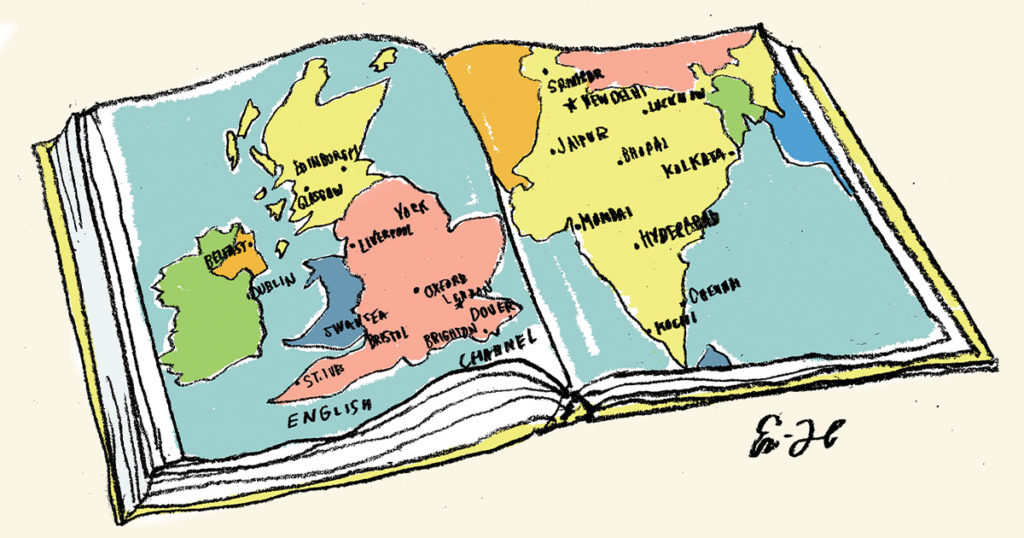

Previously, while reading, I would hear a voice in my head saying, Don’t get up. Stay on the page. You don’t really need to know where Ulan Bator or Burma or Lyme Regis is. You’ll lose the pleasure of the story … don’t go! That voice had sharply circumscribed my life, like the tiny pencil in my childhood compass, creating a neat, small world beyond which things at any distance became somewhat imaginary. Now I made good friends with that voice—and learned to ignore it. I doggedly forced myself to look up all the places I came across, as well as places I’d previously never bothered to check. El Salvador. Taganrog. The China Sea. The Chesapeake Bay. Ypres. Ohio. St. Petersburg. Palau. Kathmandu. Even when my eyes ached, I turned to my new atlas and squinted at the minuscule print in the dizzying key, then flipped to the specified page and scanned for the point on the grid where the lines would intersect. Then came the pang of shock as the inchoate snapped into proportion and actuality. Many things immediately made greater sense. Oh, Liverpool is on the coast! And on the River Mersey! (I knew both these things without knowing them.) It’s right across the Irish Sea from Dublin—no wonder it has vast shipyards and Paul McCartney has Irish charm!

It occurred to me that every student going off to college should be equipped with a paper atlas. With the Internet, a dictionary may no longer be essential—what can you discern about the meaning of the word franklin by seeing it surrounded by frankincense, Frankish, frangible, and frangipani? Nothing is lost by looking up the word online. Fine for it to float unmoored onscreen. But a paper-and-ink map delivers a story about location and place and, more important, converts the fantastical and amorphous into a precise location you can reach, filled with people you can help or hurt, contiguous with your own reality. I gave a compact softcover atlas to my friend Claire when she was leaving for college but extracted a promise: whenever you come across a place’s name, you will open the atlas and find it.

When I think about why it took me so long to do as much, I realize that for me, books had been a refuge rather than a resource. When I was a child, the entire nonfiction section of the library seemed tedious. Only fiction seemed real. Outside life was jagged and overwhelming. Inside a novel, progressing down the corridors of sentences, I felt both soothed and involved in something scintillating. I often kissed the inner stitched binding of a library volume, as I’d been taught to do before shutting a prayer book; I wanted to honor the intimate secret hinge. I was the youngest of four, my big sister domineering, my two brothers kinetic and loud. Our mother, meanwhile, was often depressed. Books had all the time in the world for me, and a glimmering, powerful clarity, and told me what it was like to be inside someone else—what it was really like. I didn’t think they needed supplementing.

If I didn’t know the meaning of a word, I didn’t check. If I came across a place name, the music of its syllables assured me that I understood enough to simply read on. In addition, I grew up at a time when girls and women were coaxed toward domesticity; our archetypal stories heroized the home. My brothers were encouraged and also pressured to educate themselves into a practical profession. One became an engineer, the other a doctor. My sister held down a position at a state employment agency but sang opera in the evening. I was allowed to become a writer. This was a double-edged blessing. I could maunder on in pleasurable realms, but without gaining purchase on outside reality.

When I got the cheap atlas, I scrawled notes in its margins and inked circles around important spots. When I found Treblinka on a map of Poland, the arrangement of the letters—their shape as recognizable and shocking as a face intentionally forgotten—seemed to declare: Yes, what you read is true. The same of Sevastopol, in Crimea. And even, in a different way, St. Ives, the Cornish seaside town where Virginia Woolf summered as a girl. It was as if each place name were a button stitched to the planet, and now instead of billowing indeterminacy, there was a tailored shape, an exact location, which seemed to reinvent me, or rather to sew an understanding deep within me. Locales emerged from the diaphanous fairytale realms of Narnia or Brigadoon, having attained a gritty particularity. The sensation was so exciting that I felt as if my fingers were being curled around a captain’s wheel of knowledge that could turn even the fate of continents. Not only that: the people who lived in these places accrued distinction. They were not ghosts; they were flesh-and-blood aunts and uncles, fathers and mothers and kids.

All of this is quite different from what happens with the answer box of the computer, which instantaneously supplies a map that swims in the same space as everything else on the Internet, accurate but evanescent.

The book of maps, and my determination to use it, ruptured a preference for immersion rather than information, and taught me how fully one supplements the other. Patti Smith’s Deptford, New Jersey, and Saidiya Hartman’s Accra, Ghana, have gravitas because I know where these places are. Satyajit Ray’s Bengal also exists for me, its location on the map bridging the distance to the black-and-white images I saw at the movies. Stitching mind to matter has grounded me in life. As Emerson wrote, “Let us treat … men and women well: treat them as if they were real: perhaps they are.” The map book is one way to make them so.

Piece by piece we assemble our world, some of us more quickly than others, and some of us in ways that make the far away seem real and the strangers quite possible to reach.