The Undertow: Scenes from a Slow Civil War by Jeff Sharlet; W. W. Norton, 352 pp., $28.95

Jeff Sharlet’s new book, The Undertow, plunged me into a vertiginous fever-dream. It induced a physiological response similar to the one I experienced while reading Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem. Both books are mood-altering, mind-altering odysseys; both set forth visions of a weird and roiling body politic. Didion’s title invokes an earlier account of disintegration, W. B. Yeats’s “The Second Coming,” to frame its anatomy of American chaos in the 1960s. “Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, / The blood-dimmed tide is loosed,” Yeats wrote in 1919. “And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,” he wonders in the poem’s final lines, “Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?” This is the question hovering behind Sharlet’s essay collection, which spans a period of approximately 10 years, ending in 2021—an era he describes, borrowing filmmaker Jeffrey Ruoff’s coinage, as “the Trumpocene.”

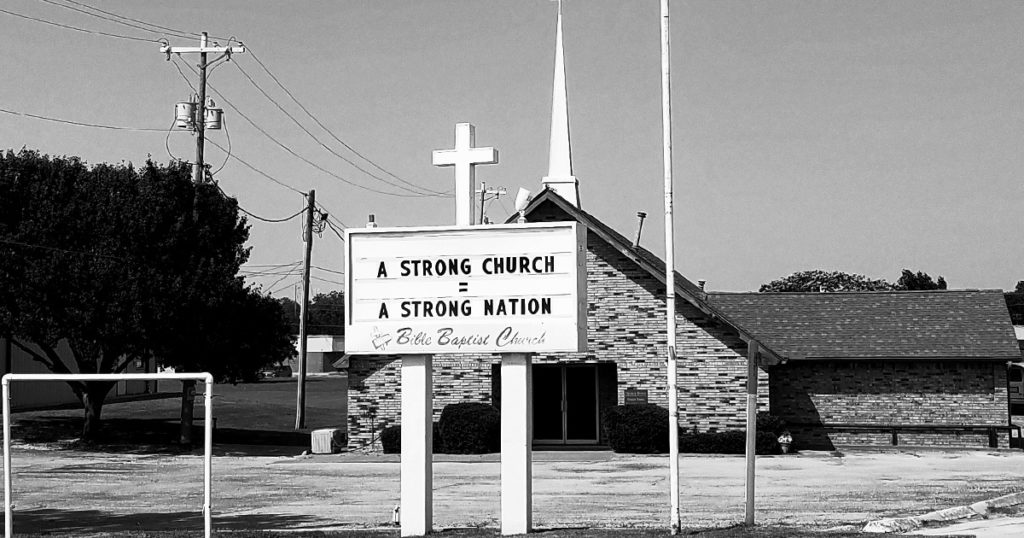

On finishing The Undertow, I realized the degree to which the revelatory terrors of Didion’s American surreal are mercifully muted for me because I am not old enough to have known them at first hand. But I live in Sharlet’s America, a world of apocalyptic pulsings and unnatural peril made all the more visceral by the author’s capacity for ventriloquizing the grief, rage, delusion, racism, misogyny, and bad-faith histrionics that he encounters on his journeys across the United States. The river of bile on which Sharlet fights to stay afloat courses from one end of the country to the other. He ushers us into the front yards and houses of radicalized private citizens, draws us into a conference for angry members of the “manosphere,” sweeps us from the violence of the Capitol steps on January 6 to the conspiratorial depths of QAnon. He immerses us in political rallies and megachurch services, which often sound very much the same in their embrace of a prosperity gospel derived from Norman Vincent Peale’s The Power of Positive Thinking (1952). The same association between faith and material success that makes the “church of Trump” appealing to so many infuses some of the actual churches Sharlet visits.

A consummate long-form journalist and a professor of creative writing at Dartmouth College, Sharlet is also the author of several books, including The Family: The Secret Fundamentalism at the Heart of American Power (2008) and C Street: The Fundamentalist Threat to American Democracy (2010), which together formed the basis of a Netflix documentary series. The evangelical Christian communities that Sharlet explored in those works feature in The Undertow as ecstatic, often paranoid, and usually armed. The book alludes to the long, sometimes violent history of American evangelism that stretches back to the Puritans—a history eloquently traversed several years ago by another intrepid journalist, Frances FitzGerald, in The Evangelicals (2017). Figures like Jonathan Edwards and John Brown make cameos in Sharlet’s book, but its focus is, emphatically, on the now. The Undertow, Sharlet advises readers, “is written from the middle of something, a season of coming apart.”

Sharlet is a kind of anthropologist of the Trumpocene, and the richness of his dispatches derives from his ability to inhabit a broad range of sensibilities and psychologies. Camping out in the “funk” of Lower Manhattan’s Zuccotti Park in 2011, for example, he tries to account for the oddness of the Occupy movement. “Occupations were literally about re-filling a hollowed-out public sphere with an actual public of breathing bodies,” he writes. The protesters made headlines, even as their agenda remained somewhat unclear. They were, he concludes, holy fools: they offered poetry instead of platforms and spoke “not truth to power but imagination to things as they are.”

Despite this interlude, Sharlet is interested primarily in the imagination of the right. In his telling, it assumes more sinister expression as cant, violent fantasy, and vengeful prayer, which combine to create an “alternate reality” bolstered by “the juxtaposition of the verifiable and the absurd, each vouching for the other.” The Steal, Pizzagate, the deep state, red-pilling, the Great Replacement Theory, the satanic Clintons—these are the “feverish dreams” coursing, in their various permutations, through the book. These are the descendants of dreams, Sharlet insists, that have been “twisting through the American mind since the beginning.”

Sharlet, who has attended services in all manner of places—“megachurches and chapels and compounds and covens”—visits several in The Undertow. An early essay features Miami’s slick, celebrity-linked VOUS Church, “born on an Oxygen reality show featuring beaches, bikinis, and screaming fans, called Rich in Faith.” Sharlet’s handlers are friendly, keen that he have “fun,” but he finds only emptiness: a gospel of “style and good feeling.” Later, he attends the more “militant” and considerably less hospitable West Omaha Baptist Church, where Pastor Hank singles him out as a journalist purveying lies: “Your sin will find you out.” What finds him out first, when he is talking with some worshippers in the parking lot after the service, is an obviously armed security guard and an usher, who persuades Sharlet to leave with a threatening question: “How do you know I don’t have a gun?” The incident raises Sharlet’s blood pressure and brings into focus the autobiographical story that threads through his narrative. He reveals that he has had two heart attacks, and so the heartsickness of the body politic finds its physical analogue and somber echo in the heart disease of its chronicler, as he is dragged, and we with him, into the undertow of a distinctively American kind of sorrow and hysteria.

In The Undertow’s title essay, Sharlet takes up the case of Ashli Babbitt, the January 6 rioter killed by a Capitol Police officer. For some, Babbitt has become a martyr, a harbinger, the “first casualty” of the “slow civil war” to which the book’s subtitle calls our attention. Her death, together with the swirling fictions about it that have now replaced the facts, becomes the emblem of a Yeatsian center that “cannot hold.” Yet the book’s first and final essays offer a counterpoint to the processes of disintegration and drowning in the portraits of two musicians and political activists: Harry Belafonte and Lee Hays (a founder of the folk group The Weavers). Sharlet restores the voices of these singers, whose “best songs” have been “forgotten or worn smooth and seemingly safe by time.” Rescuing their music from the distortions of history, he reveals these artists in all their lyrical splendor as mourners, elegists. Sharlet sees these men—one Black, the other white—as heroic singers of “a kind of secret code of resistance” to lies, delusions, and Trumpian “vulgarity masquerading as candor,” as well as to the violence such rhetoric summons.

Remember grieving Orpheus, torn limb from limb by the frenzied bacchantes, his head carried along the river, still afloat and singing. Nothing could drown out that voice.