The Gogol Notebook

Remembering Randall Jarrell’s passionate lectures on Russian literature and discovering the pangs of alienation that plagued the poet during his final years

Poet and critic Randall Jarrell, one of the most prominent American intellectuals of the mid-20th century, taught a seminar in Russian literature at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro in the fall of 1964. I was an MFA student in fiction at the time and a member of Jarrell’s class—the last he saw through to the end before his death at the age of 51. One night in October 1965, Jarrell was killed by a car when walking along a highway in Chapel Hill. Although the driver said Jarrell had “lunged” at the car, the coroner ruled the death an accident for lack of sufficient evidence to confirm suicide. (He also concluded that the driver was not at fault.) Jarrell’s wife, Mary, always maintained that his death had been accidental, but his friends were convinced that he had killed himself. Jarrell’s biographer William Pritchard has pointed out that although the circumstances of Jarrell’s death will always remain unclear, something in him evidently “gave way” during his final years.

I saw that giving way in Jarrell’s seminar. Though his lectures, most of them about Nikolai Gogol, were mesmerizing, he sometimes seemed agitated and depressed. He occasionally veered into obsessive talk about Johnny Unitas, the quarterback nicknamed the Golden Arm, who was leading the Baltimore Colts to the NFL championship game that year. Jarrell, an avid football fan, told us of a recent encounter with Unitas on an airplane. Jarrell greeted his hero rhapsodically, but—to his dismay—Unitas had never heard of him, one of America’s most celebrated poets. Otherwise Jarrell was focused on Gogol, the wildly inventive, tormented Russian genius who himself committed suicide during a crisis in his writing life.

I had known Jarrell since I was in high school—I thought of him as Randall then. He and Mary were friends of my writer parents (my father was a historian, my mother a journalist), and Mary’s daughter Beatrice was my friend. The Jarrells frequently visited our Greensboro home on summer afternoons for picnics and tennis, Randall, my mother, and my brother in tennis whites, my father pouring lemonade from a silver pitcher. Sometimes other friends from town joined them, drawn by my mother, a nationally ranked player in her youth. She and Randall—a former tennis coach at Kenyon College—were fierce competitors; in doubles they were always on opposite sides of the net. Privately my mother fumed that Randall “cheated” by stamping his feet during her service; my brother, whom our mother was grooming for tournament play, and who sometimes partnered Randall, said that Randall dominated their side of the court, sliding over for a shot with an “I got it.” But the play seemed cheerful, the hypnotic sound of long volleys punctuated by Randall’s cries of “Peachy shot!” Mary watched the play from the sidelines. Between points, she and Randall blew kisses to each other. “Hello, pussycat.” “Hello, pussycat.”

Randall was in his prime then as a writer, a star in the literary pantheon that included his friends Robert Lowell, Robert Penn Warren, John Berryman, and Peter Taylor. Just back from a year in Washington, D.C., where he had been poetry consultant to the Library of Congress (a position now referred to as poet laureate), he had published five volumes of verse, a brilliant collection of essays, Poetry and the Age, and a witty, acerbic novel, Pictures From an Institution, which drew on his year of teaching at Sarah Lawrence College. During the days of tennis and lemonade, he was working on The Woman at the Washington Zoo, a book of poems that would win him the National Book Award in 1961. He radiated self-confidence and joie de vivre.

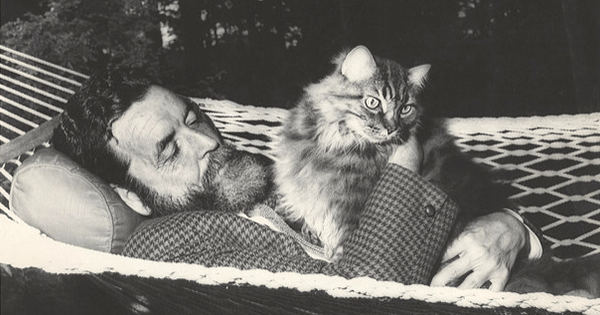

Randall was a person of rapturous enthusiasms. “Gee, that’s dandy!” he would frequently exclaim. He drove a white Mercedes sports car and, when not on the court, dressed in tailored Saville Row jackets, ascots, and wide-brimmed fedoras. He had a full beard (rare in those days)—black, daubed in front with white, as by a paintbrush—and he was slender and lithe. His interests were wide-ranging: my father’s unusual plants (marsh pennywort is one I remember), birds, the night sky, ice hockey, the Washington Redskins, stock-car racing, Freud (a bust of the father of psychoanalysis stood in his living room), Goethe (whom he was translating), Paolo Uccello, Ulysses S. Grant, the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm, England and Germany (where intellectuals hadn’t been banished from public life, as in America), and the TV show Gunsmoke (he and Mary made no engagements on Saturday nights, when it was playing).

His house seemed enchanted because he felt that it was. He spoke of the chipmunks and squirrels and the mockingbird in his yard as if they were creatures in his private fairy tale. The bat family that lived on his porch was more interesting than other bats and inspired his elegant children’s book, The Bat-Poet. When a sprig of ivy poked through a wall into the Jarrells’ kitchen, we were invited over to see the horticultural miracle that could occur only in a poet’s house.

His chief passion was for books, and his friends rose and fell in his estimation depending on whether or not they shared his enthusiasm for a particular writer or book. You would feel you had disappointed him, his colleague Fred Chappell said, if you didn’t admire the same writer he did. Robert Lowell went further: you had to like not only the same writer, but also the same book and passage. And if you wrote something that seemed to Jarrell “a falling off,” Lowell said, “there was a coolness in all one’s relations with him. You felt that even your choice in neckties wounded him.”

As a reviewer and essayist, Jarrell could be generous, even ecstatic (his introduction to Christina Stead’s The Man Who Loved Children saved that novel from obscurity), and he wrote important, measured essays on Robert Frost and T. S. Eliot (his two major influences), as well as Wallace Stevens, Elizabeth Bishop, and Marianne Moore. But his reviews of new volumes of poetry for The Nation and The New Republic were noted, and feared, for their caustic wit. “He was a terror of a reviewer,” Berryman said. Lowell added that Jarrell was “immensely cruel, and the extraordinary thing about it was that he didn’t know that he was cruel. He had a deadly hand for killing what he despised.” In her memoir Poets in Their Youth, Berryman’s wife, Eileen Simpson, said that Jarrell was “a whip. … A whip looks benign when it’s standing in a corner, but once it’s cracked—watch out!” Jarrell had used the whip in a review of an early Berryman collection, in which he said the characters in the poems were “like statues talking like a book.”

As a child, I knew nothing about the reviews, and I’d never had an adult conversation with Randall. But I discerned that beneath his rapturous praise of whatever merited his attention—a fabric, a painting, the shape of a tree—was scorn for anything that was ordinary or imperfect. As a diffident teenager, I was painfully aware of my imperfections.

And now I was in the MFA program, which Jarrell disdained for its professionalism. He had no use for literary analysis of any kind; Lowell said he had never even heard Jarrell use the word metaphor. He summed up his feelings about literary critics in an essay titled “The Age of Criticism,” in which a group of critics at a bacon conference chide a pig that has tried to join the conversation: “Go away, pig! What do you know about bacon?”

I was nervous about being in Jarrell’s class, afraid I wouldn’t measure up to my smart parents. In fear of being called on, I sat in the back row with most of the other MFA students. A few brave souls (most likely undergraduates, of whom he was fonder) were scattered about in desks closer to Jarrell. Mary, who attended all her husband’s classes during this time, sat front and center, facing his desk.

When Jarrell entered that first day, I was surprised to see that he had shaved his beard. I thought his face looked vulnerable and sad. Until he began to teach. Jarrell’s classroom method was to read aloud, with such vivacity that he lifted the writing off the page. Along the way, he pointed out passages that were extraordinary or wonderfully odd. Chekhov, Turgenev, and Tolstoy were on the syllabus, but they received scant attention. That semester he was in love with Gogol.

He performed Gogol’s satirical play The Inspector General in its entirety, in his high-pitched marveling voice. He took all the parts, most memorably Khlestakov, whom some foolish townspeople mistake for an inspector come to find fault with their governance, and the hilarious yes-men, the fat, idiot twins Bobchinsky and Dobchinsky. (Jarrell was so taken with this pair that he and Mary began to call each other Bobchinsky and Dobchinsky, Mary wrote in her essay “A Group of Two”; previously their private nickname had been the Bobbsey Twins.)

When Jarrell read “The Overcoat,” the first short story in Western literature about an ordinary, alienated person, he displayed more empathy for its protagonist than he seemed capable of in ordinary life. Akaky Akayevich Bashmachkin, a poor clerk scorned and bullied by his fellow workers, shivers against the Russian winter in his threadbare overcoat. After months of penurious saving, he engages a tailor to make him a new coat, but before long, he is robbed of the coat and dies of grief. Part of the genius of the story lies in the absurd, bathetic details that Jarrell relished; I remember his calling attention to the tailor’s snuffbox, “adorned with the portrait of some general—just what general is unknown, for the place where the face had belonged had been rubbed through by the finger, and a square of paper had been pasted on.” But when Jarrell read aloud the line of great pathos that leaps from the heart of the story—“I am your brother”—his voice was full of sorrow.

A humorous, poignant, and less well known story is “Ivan Fyodorovich Shponka and His Aunt.” Shponka, a young man entirely lacking in confidence, has a tortured conversation with a woman to whom his aunt wishes him to propose. They sit in silence until, after a quarter of an hour, he manages to say, “There are a great many flies in the summer, ma’am.” “Yes,” she replies, “ever so many,” adding that her brother “made a flyflap of mother’s old slipper, but there are still lots of them.” Silence falls again. In his reading, Jarrell brought alive the suffering that lay beneath the surface of that banal conversation. It was my first instruction in how to write dialogue.

Jarrell began each class with a reading from a biography of Gogol that he had written in the pages of a student composition book. He sat at his desk, calmly turning the pages, as he recounted the particulars of Gogol’s early life, but when describing Gogol’s pain in the later years and the conflicts that led to his horrific demise, Jarrell rose and paced the floor.

I attended a recent convocation at UNC–Greensboro on Randall Jarrell and his students (one of three symposia on Jarrell arranged by poet-in-residence Stuart Dischell). Although I was not on the panel—no one was aware that I had been Jarrell’s student—I spoke from the floor about the Russian literature class and Jarrell’s infectious passion for Gogol. (I have taught Gogol to creative writing students throughout my career, pointing out many of the same details that Jarrell relished.) But at the time, I confessed to the group, I had been so intimidated by Jarrell that I had managed to avoid writing a paper or taking the final exam. When I went in, hangdog, at the end of the semester, Jarrell said, in a chipper voice, “All right, then, who’s the best writer, Gogol, Chekhov, or Turgenev?” Of course I knew the answer—Gogol—but was astonished when he said, “All right, you get an A for the course.” I never knew why he allowed me such an easy pass—his emphasis on taste? his friendship with my parents?—but I made the mistake of talking about it and was subsequently given an oral exam by the head of the department and Jarrell’s colleague, poet Robert Watson. (I still emerged with an A.)

I mentioned to the students, poets, and scholars convened in Greensboro the biography of Gogol that Jarrell had written for our class. I wondered aloud if it still existed. No one knew, though a while later, Jim Clark, head of the MFA program at UNC–Greensboro, called to tell me that he’d discovered the biography in Jarrell’s papers, in the university library’s manuscript collection. I sat at the table and caught my breath as the librarian placed before me the familiar, green-speckled composition book. On the front, in orange crayon, is written: Gogol. Roughly a quarter of the book—some 100 pages—is devoted to Gogol’s life and work, recorded in the elegant, precise handwriting I remember so well. The rest of the pages are blank. The text is not divided into lectures, resembling instead a continuous draft for an essay in progress. And I quickly saw in Jarrell’s anguished account of Gogol’s death an uncanny foreshadowing of his own.

As I began to read, the years fell away. Jarrell is telling Gogol’s story once again.

On the first page, Jarrell notes the facts of Gogol’s early life. Born in 1809 in Ukraine—the source of much colorful detail in his early work—he was a lonely child of unfortunate physiognomy, his face dominated by a long nose (the impetus no doubt for his absurdist story “The Nose,” in which a man wakes up without a nose, which is later found in the baker’s bread; in another iteration, the nose is seen getting out of a carriage, in the uniform of a state councilor). Gogol’s schoolmates ridiculed him, calling him “the mysterious dwarf.” As a young man, when he attempted to teach history—a subject about which he knew little—he was laughed out of the classroom. Often rejected by women (a fate he bestowed upon Ivan Fyodorovich Shponka), Gogol never found a wife. His only comfort was in writing.

Although Gogol received mixed reviews from critics, Pushkin and Turgenev admired and were influenced by his work. (Later, Dostoevsky famously said, “We all come from Gogol’s Overcoat.”) Money was a problem, as was his lack of self-confidence, which expressed itself in peevishness and neurotic swings in behavior. His final published book was Dead Souls, a novel about the enterprising character Chichikov, who buys and sells the identities of dead souls (serfs) still listed as landowners’ property. Moscow’s censors were outraged. Jarrell summarized their reactions this way: “Soul immortal! Attack on serfdom! Others will start buying dead souls! Scare away tourists from Russia!” Gogol finally got around the censors by renaming his book The Adventures of Chichikov, or Dead Souls. But he was shaken.

Although he wrote a second volume of Dead Souls, and part of a third, he fell under the influence of religious fanatics who said he should not publish them on moral grounds. Such treatment of souls was so heretical that he was accused of being possessed by the devil. Two people in Gogol’s immediate circle, Count A. K. Tolstoy and the rabid priest Father Matthew Konstantinovsky, played a crucial role. The priest “continually threatened Gogol with hellfire and damnation if Gogol didn’t obey him” about destroying the manuscripts, Jarrell wrote. “Gogol is reported to have cried out, ‘Leave me alone. I can’t bear it any more. It’s too terrible!’ Gogol … insulted Father Matthew for his demands—then wrote asking forgiveness.” In desperation, he went to the lunatic asylum intending to talk to a well-known seer about his conflict, but after walking up and down in front of the gates, he left without going inside.

As Jarrell wrote, one February night Gogol prayed a long time. At three in the morning, he summoned his boy-servant Semyon, asking for his cloak, and from there, they proceeded to the drawing room. Gogol, “with lighted candle in hand,” asked the boy to retrieve his briefcase from the cupboard. The writer took a bundle of manuscripts, which contained the second part of Dead Souls, put the pages in the stove, and then lit it with the candle, ignoring Semyon’s protests. When the fire went out, with only the corners of the pages charred, Gogol untied the ribbon around them, separated the pages, and lit them. He then “sat down and watched his last ten years’ work burn. Then, crossing himself, [he] returned [to his] bedroom, kissed Semyon, sat on the sofa and wept.”

From that day forward, Gogol refused to eat. He committed suicide by starvation. If he could not write, he would not live.

That fall, Jarrell was taking Elavil for depression; the next spring, he was prescribed Thorazine, which he said made his mind feel so empty that he could not write. He wrote very little between 1963 and the time of his death in 1965; he was suffering from a creative paralysis himself when he wrote Gogol’s biography in 1964.

To this point in the biography, Jarrell’s script is clear and legible. In the final pages, as he describes Gogol’s death, the handwriting becomes urgent, the words larger, the sentences full of scratched-out phrases and tortured repetitions. I remember the class in which Jarrell told us about Gogol’s end. He was standing by the window, in my memory the sky appropriately overcast, his expression somber. The priest and Gogol’s doctor fought to keep him alive, given that suicide was a sin. They forced broth and calomel down his throat, gave him hot and cold baths, applied leeches to his nose, causing Gogol to scream: “ ‘Take off the leeches! Take them away from my mouth!’ But the doctors paid no attention to him and kept them on for a long time, pinning down his hands to prevent him from touching them. At 7 o’clock more doctors arrived. [They] ordered the application of more leeches as well as of mustard plasters to his legs and ice on his head, and forced him to swallow some medicine. They treated him like a lunatic, shouting at the top of their voices as if he were already dead. …

“But his breathing soon became heavy, his face grew thin, dark patches appeared under his eyes and his skin grew cold and clammy.” On the last night of Gogol’s life, the doctor, a professor of medicine at Moscow University, “spent several hours at [Gogol’s] bedside … giving him calomel and putting hot loaves of bread around his body, Gogol uttering piercing cries all the time. He died at 8 o’clock in the morning of February the 21st, a month before his forty-third birthday.” I remember Jarrell’s long pause. It seemed that he might weep.

Gogol’s body lay in state, a laurel wreath around his head. “All Moscow turned out for his funeral on Feb. 25th,” Jarrell wrote; the government was so alarmed by the public response that no mention of Gogol’s death was allowed in the newspapers. When Turgenev “managed to publish [a] short obituary in a Moscow newspaper, calling Gogol a great man, [he] was arrested and exiled to his estate.”

Part of Gogol’s legacy, according to Jarrell, was that in writings such as “The Overcoat,” The Inspector General, and Dead Souls, he “showed the tyranny and corruption of the Russian state, helped to convince Russian readers (and the Russian writers [influenced] by Gogol) that the Russian people must be saved from the Russian government. … [He] helped to free Russia, to give it a radical, secular salvation.” Equally important, in Jarrell’s view, was Gogol’s genius for characterization: “Nobody has ever expressed better the trivial, vulgar, inconsequential side of man, the wish-fantasy side of man’s nature—what Freud calls the pleasure principle, the primary principle that later is revised, ruled over, rationalized by the ego and superego; … Gogol takes [human] vanities—[the] word has two meanings here: (1) trivial inconsequential nothingness, (2) complacent conceitedness—and makes them into something at once absurd and sublime.”

At the end of the biography, Jarrell returns to Gogol’s play The Inspector General:

One of the most sublime assertions of human dignity, at a fundamental level, occurs at the moment when that short fat little twin, Peter Ivanovich Bobchinsky, said to Khlestakov, “I have, sir, I have a very humble request, sir.”

Khlestakov says, “What is it?”

And Bobchinsky answers: “I’d like to ask you, sir, when you go back to Petersburg, to say to all the grand gentlemen there—senators and admirals—that ‘You know, Your Highness, in such and such a town lives one Peter Ivanovich Bobchinsky.’ ”

Jarrell identified with this wish, projecting onto Bobchinsky his own longing to be known and remembered. His consternation in 1964 that Johnny Unitas didn’t recognize him was not just a slightly comic, narcissistic reaction; for Jarrell it was an indication—a point he had argued for years—that poetry didn’t matter to most Americans.

In “The Obscurity of the Poet” he wrote, “Any American poet under a certain age, a fairly advanced age … has inherited a situation in which no one looks at him and in which, consequently, everyone complains that he is invisible, for the corner into which no one looks is always dark.”

Jarrell tried to make this same point—tying it to the Unitas encounter—when he introduced Hannah Arendt, who gave a lecture in Greensboro in early 1965. Those of us in the audience remember that Jarrell went on for an incoherent, painful 40 minutes. Afterward, a friend of Jarrell’s told the English department head that Jarrell needed medical care, and he was taken—willingly—to the psychiatric ward at the university hospital in Chapel Hill.

In one of Jarrell’s final poems, “Next Day,” from his last book, The Lost World, the poet assumes the persona of an aging housewife who says plaintively that she wants the boy putting groceries in her car to see her. She isn’t noticed; she is vanishing. The day before, she had gone to the funeral of a friend who had told her how young she seemed. “I am exceptional,” she tells herself.

I think of all I have.

But really no one is exceptional,

No one has anything, I’m anybody,

I stand beside my grave

Confused with my life, that is commonplace and solitary.

Writing in The New York Times, Joseph Bennett gave The Lost World a savage review in April 1965, accusing Jarrell of “familiar, clanging vulgarity, corny clichés, cuteness and the terrible self-indulgence of his tear-jerking bourgeois sentimentality. … Folksy, pathetic, affected—there is no depth to which [Jarrell] will not sink, if shown the hole.”

Bennett’s motivation must certainly have been, at least in part, retaliation for Jarrell’s attacks on other poets. Regardless, the Times review marked the beginning of Jarrell’s final descent. A few weeks after it appeared, he slashed his left wrist with a knife, leading to another stay in the Chapel Hill psychiatric ward.

During the summer, Jarrell left the hospital but gradually became alienated from most of his friends and from his wife. He was back at the hospital, receiving physical therapy for his wrist, when he wrote to his friend the editor Michael di Capua that he and Mary were separated and would be divorced.

Jarrell was very much alone in Chapel Hill when he chose to walk at night along the dark highway—instead of on streets nearer the hospital—and was killed. Even if he did not deliberately step in front of the car, it seems clear that he was possessed, in Freud’s term, by a death wish.

At the end of the Gogol biography, after describing Bobchinsky’s request as “one of the most sublime assertions of human dignity, at a fundamental level,” Jarrell concluded with a paragraph in which one hears not only Bobchinsky’s desire for a legacy and Gogol’s right to it, but Jarrell’s yearning as well: “Beyond this [desire to be known] we cannot go: here man’s only claim on existence is his own existence, and he is satisfied with it: he was, he wants the world to know that he was, and that is all.”