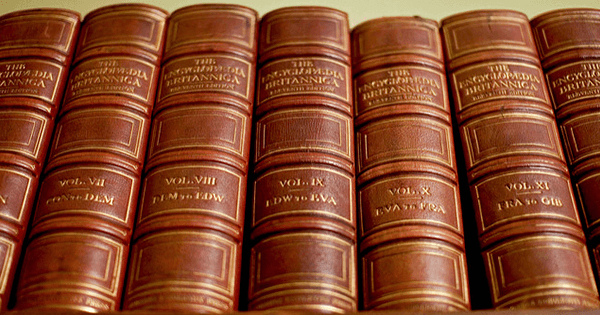

Everything Explained That Is Explainable: On the Creation of the Encyclopaedia Britannica’s Celebrated Eleventh Edition, 1910–1911 by Denis Boyles; Knopf, 464 pp., $30

Forty-four million words, 40,000 entries, and 28 volumes. More than 1,500 contributors shepherded by 64 editors, with an editorial budget in today’s money of $30 million. By any yardstick—and you’d need at least one to measure it on a bookshelf—the Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica was a beast. More than a century after its publication, it still casts a long intellectual shadow. With an author roster drawn from history’s Who’s Who—George Bernard Shaw, Ernest Rutherford, John Muir, and Bertrand Russell, to name but a few—it became the first encyclopedia to sell more than a million copies. Today, it lives on in countless printed anthologies and digital reproductions, and as feedstock for Wikipedia.

Less well known is the visionary hucksterism behind its birth. In Everything Explained That Is Explainable, Denis Boyles brings to life a rollicking saga of outlandish schemes, copyright theft, lawsuits, buyouts, and bankruptcies. The Eleventh is rightly hailed as the pinnacle of Edwardian learning. Yet as Boyles, a columnist for Men’s Health and the editorial director of Nova Media in San Francisco, makes clear, its proprietors also revolutionized publishing in the United States and Great Britain, with lessons that click through to the Internet Age.

The EB began in 1768 with three volumes published by the self-styled Society of Gentlemen in Scotland. By the second half of the 19th century, it was arguably first among equals in an expanding global universe of reference books. Rolled out from 1875 to 1889 in 24 volumes, its magisterial Ninth Edition, studded with authorities like Thomas Henry Huxley on evolution, James Clerk Maxwell on the physical sciences, and Prince Peter Kropotkin on Russia, won worldwide acclaim. But profits failed to meet expectations, not least because the United States, Britannica’s biggest market, remained the copyright equivalent of the Wild West. All told, more than a dozen pirated and Americanized versions sold four times as many copies as the legal original.

Yet even as the EB’s beleaguered British publishers increasingly saw it as an albatross—too out-of-date to sell more copies, and too expensive to update—one American bookseller named Horace Everett Hooper saw an opportunity.

In 1896, backed by his Chicago publisher, James Clarke, and his partner, Walter Montgomery Jackson, the head of the Grolier Society, which specialized in expensive reprints, Hooper bought the rights to the EB’s Ninth Edition, including 5,000 sets, the plates, and any remaindered stock. Hooper intended to contract with The Times of London, another British institution in parlous shape, and sell the EB under the venerable newspaper’s imprimatur.

It was as if an American freebooter in a rowboat were trying to board and capture Lord Nelson’s flagship. But Hooper had a few things in his favor. First, as Boyles notes, “Hooper understood that his business wasn’t just publishing reference books. It was monetizing authority.” And few things radiated more authority than the EB and The Times, which Hooper saw, in Boyles’s words, “as the great stone lions guarding the entrance to an edifice that was the product of applied Anglophilia.” Not only was the staid British publishing world ripe for disruption—book ads in The Times, for instance, were as sober as death notices—but Hooper could also deploy both his tested sales methods and the well-oiled pitching skills of a flamboyant Hearst newspaper journalist named Henry Haxton. Last but not least, the faltering Times, under siege from cheaper, sensationalist papers and burdened by a byzantine corporate structure, badly needed Hooper’s help.

The partnership first bore fruit in a sales proposition that would have made P. T. Barnum proud: the 1898 marketing in Britain, under The Times’s imprint but with no new content, of an encyclopedia whose first volume had come out two decades earlier. What was new was the bombastic full-page ads in The Times and other publications, the unprecedented installment plan, coupons, and gee-gaw premiums like a revolving oak bookcase for your spiffy new set. Notwithstanding jokes that “The Times was behind the encyclopedia, but the encyclopedia was behind the times,” the money poured in.

Over the next decade, the EB and The Times flourished in somewhat tumultuous symbiosis. Hooper, meanwhile, was fixated on bolstering the newspaper with racy new display ads for Rose’s lime juice and other consumer products. To increase circulation, he also hatched an innovative plan for a Times book club: those who purchased a Times subscription could borrow books and then buy them—much to the anger of British booksellers—at a discount.

These and other herculean marketing efforts both kept The Times alive and underwrote the daunting cost of creating a fresh Eleventh Edition from nearly the ground up. Rather than publish one volume at a time and use its profits to finance the next, Hooper and the Eleventh’s editor Hugh Chisholm conceived it as a unified project to be published in one swoop. No longer would a newer volume contradict or superannuate those that had come before it. The Eleventh’s great achievement would be to present a cohesive, unitary view of knowledge without much disturbing the individual styles and opinions of its distinguished contributors.

Yet it almost didn’t come to pass. In 1909, the year before the Eleventh’s debut, a rupture ensued between Hooper and his partner Jackson, who fretted over the former’s expensive ambitions. Out of money, Boyles writes, “the great Encyclopaedia Britannica ground to a halt.” Worse, the nasty publicity surrounding the legal spat cost Hooper his partnership with The Times. Undaunted, Hooper set out once again to “leverage one major ‘brand’ against another,” forging an agreement with Cambridge University. In return for lending its name to the project, one of Britain’s two greatest universities would get a five percent royalty on each set sold.

Published in December 1910, preceded by over-the-top ad campaigns and lavish launch parties, and greeted by overwhelmingly positive reviews, the Eleventh summed up the spirit of the age. As Boyles observes, “optimism was the logical conclusion to every line of inquiry, and proof of progress was everywhere you looked, on nearly every page.” (He rightly notes that spirit’s uglier side, in unabashedly racist entries on “Negro” and “Ku Klux Klan,” for instance.) In that respect, Boyles can be forgiven for the elegiac tone of his book’s ending. After all, barely four years later, the horrors of the First World War closed the book on Edwardian optimism. The conflict also crimped the Eleventh’s bright commercial prospects—not least because President Woodrow Wilson curtailed installment plan purchases as a frippery during war.

Yet long after Hooper’s death in 1922, the EB lived on. In 1943, William Benton, the head of the legendary New York ad agency Benton & Bowles and a future U.S. senator, teamed up with University of Chicago President Robert Maynard Hutchins to buy the EB, reviving its commercial and intellectual promise. (Full disclosure: my father, Frank Gibney, worked for EB for more than three decades.) In 1990, the company booked a record $650 million in revenues. That was the same year, unfortunately, that Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web. In 2012, 244 years after issuing its first set of volumes, the EB suspended paper publication—and therein hangs another business tale waiting to be told.