Aristotle’s Way: How Ancient Wisdom Can Change Your Life by Edith Hall; Penguin Press, 231 pp., $27

Who knew that Melania Trump’s “Be Best” campaign was Aristotelian? As Edith Hall, a distinguished classicist at King’s College London, explains, “becoming the Best Possible You” is a core tenet of Aristotle’s “Project Happiness,” the pursuit of which is the subject of her new book, Aristotle’s Way. Intended as a practical guide to living well, as opposed to an academic treatise, the book belongs more in the genre of self-help manuals with titles like The Power of Habit and The Road Back to You, than, say, “The Meaning of Prohairesis in Aristotle’s Ethics.”

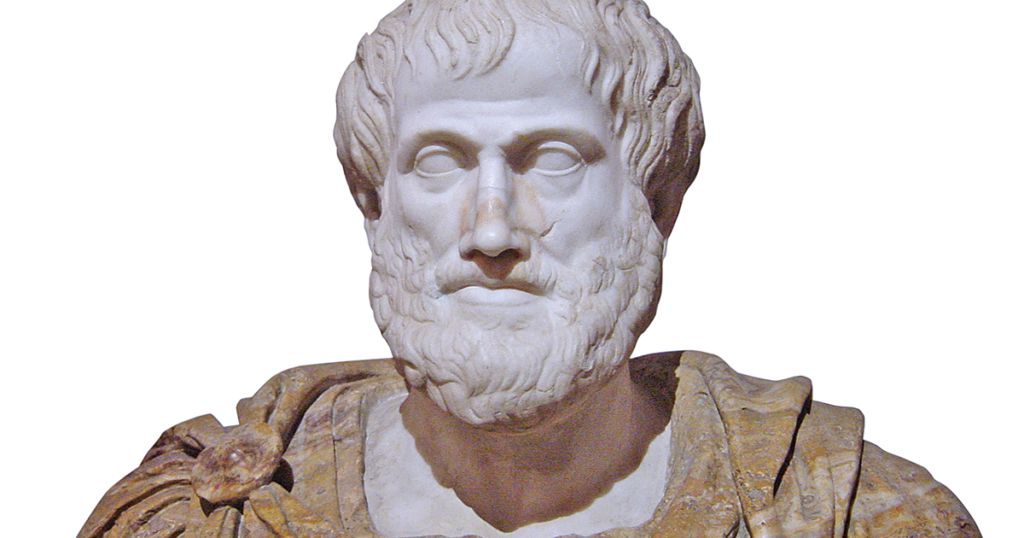

Aristotle himself was born in 384 B.C., in the small city-state of Stageira, set in the wooded, mountainous peninsula overlooking the Aegean in northern Greece. His father was personal physician to the king of Macedon, and his mother came from a property-owning family in the city of Chalkis. Both parents died when Aristotle was 13. His married sister’s family took him in, and a few years later, sent him to study at Plato’s Academy in Athens. It seems likely that had his father lived, Aristotle would have followed him into medicine, so this chance circumstance may have directed the course of Western intellectual history.

Aristotle would become the friend and tutor of kings, including most famously of Alexander the Great of Macedon, as well as the founder of his own academy in Athens, the Lyceum. Studying and pondering the world around him throughout all the ups and downs of his fortunes, Aristotle wrote some 200 treatises, of which 31 survive, examining all imaginable subjects that inform human experience. Shining among these are Aristotle’s work on ethics and, the subject of Hall’s book, human happiness. “If it is not god-sent,” Hall writes, summarizing the master, “then it comes as the result of goodness, along with a learning process, and effort.” A person can, then, work for happiness, acquire it through discipline and application, like a successful career.

The principles leading the way to happiness are dispersed among a range of treatises written in the style of lecture notes, which, as Hall states, makes them “often dense and strenuous.” She undertakes to explain them in an accessible and unstrenuous manner, organizing her discussion around broad themes—potential, self-knowledge, love, communication—and drawing upon such disparate works as the Nichomachean Ethics, Eudemian Ethics, Metaphysics, Rhetoric, Politics, Poetics, and even Meteorology and Generation of Animals.

In clear, patient language, Hall deftly weaves threads pulled from this daunting range of material into lessons that pertain directly to dilemmas of modern life. Aristotelian rules of rhetoric advocating clarity, brevity, and knowledge of one’s audience, for example, identify essential communication skills and give guidance for a modern job interview. Similarly, Aristotle was both a perceptive and compassionate observer of human nature, and his advice regarding the cultivation of virtuous qualities still speaks to those striving to “find themselves” and improve their character. We are told that Hall “first encountered Aristotle when she was twenty, and he changed her life forever”; one of the book’s strengths is her tone of unmistakable sincerity.

The book is marred, however, by a stream of clunky references to television shows and movies. Thus we are told that Aristotle did not accompany Alexander on his campaign east “despite what is claimed to have happened in Robert Rossen’s epic movie Alexander the Great (1956) starring Richard Burton”; “I felt like Antonius Block in Ingmar Bergman’s classic movie The Seventh Seal (1957)”; “Darren Aronofsky’s The Fountain (2006) reveals what it is like for a dying woman who wants her husband” to spend all time with her. The citations go on and on.

Hall’s decision to take this tack echoes Aristotle’s own: his works abound in references to the popular culture of his day. But it is one thing for Aristotle to draw upon fourth-century B.C. Greek culture to illustrate his thoughts, and quite another to draw on modern culture to illustrate Aristotle, especially as the plethora of modern citations overwhelms Aristotle’s own words. Hall’s occasional references to the philosopher’s power of expression only further tantalize. On the Poetics’ invaluable advice for writers, for example, she remarks that the “most important secrets are held in those incomparable chapters 6, 9, and 13,” but she does not quote from them. Similarly, Hall reports that Aristotle’s treatise On Memory and Recollection “is an enthralling read because of the intimacy which makes you relate to how it felt to be inside his own head,” but again offers nothing of his own words. This is unfortunate, for when she does let him speak, as in the very successful chapter on “Community,” Aristotle and his tireless, searching curiosity leap forth in vivid life.

Following a quotation of Aristotle’s about a hapless man possessed of no talent, Hall remarks that it is “unlikely that anyone who has chosen to read this book is quite as unwise as that.” Yet she does not seem to trust her readers’ acuity or patience, or the very idea that they might be as interested in Aristotle as they are in changing their lives. Circling back to an important Aristotelian observation: brevity and clarity this book has, but it does not take the measure of its intended audience.