Late in the fall of 1996, shortly before leaving work for the day, I happened to walk past the office of a colleague of mine. He was standing with his back to me, gazing out at the leafless trees, in a stance so aimless and unguarded that he reminded me of those frozen characters in Edward Hopper’s paintings who are forever staring out the window at basically nothing at all. I chose to walk by without disturbing him. I knew that he’d been shaken by his father’s recent death, and he was, I was sure, thinking of his father now. But after slipping by his door, I took a few steps back and peered into his office. “You okay?” I finally asked. He turned to look at me, smiled, aware of my hesitation. “Me okay,” he replied. He had been keeping his sorrow largely to himself, but that afternoon, he started to tell me about his father, a conversation that continued when my colleague offered to drive me home. It was during the long ride up to 110th Street that he really opened up. I’ll never forget the story he told me.

After being married all his life, his widowed father found the courage one day to reach out to a woman he had loved in high school, more than 60 years before. She too had been recently widowed, which he knew, since all through their married lives each had kept secret tabs on the other. The two were not a whit less in love than when they were high school sweethearts. I asked my colleague whether he had known about his father’s first love. No, no one even suspected. The man had always been a devoted and faithful husband, the perfect family man, and a model Orthodox Jew. And yet, I said, he must have lived with this big, gaping hole in his heart, despite the wife he must have cherished, the children he loved, the circle of friends that had gathered around him, and the business he’d built up. All exemplary, he said. And yet … he added, without finishing his sentence.

The two needed to do a lot of catching up. Nevertheless, while a part of them might certainly have wished they’d stuck together and not been married to the wrong partners—and his mother was the wrong partner, as he later found out from his father’s letters and journals—another part, while grateful for their final reunion, was surely being reminded of the life they’d missed out on, of all the years spent apart, and of how impossible it would be now to even attempt to make up for lost time. Could one ever banish the thought of having led the wrong life? How could one be happy when faced with daily reminders of so many wasted years?

He mused on the matter awhile when he parked the car outside my home. They were like lovebirds together, he said. They were so grateful for this second go at life that they took what they could and enjoyed the present without regrets, because all they had was the present. No point thinking of the years left behind, and certainly no point thinking of the future. “But under those conditions,” I said, “I wouldn’t know how to live in the present only. My mind would be constantly tossing and turning back and forth in time like someone trying to fit into clothes he wore decades earlier, or trying on hand-me-downs worn by a very fat uncle. I’d probably end up ruining the small gift given me in my final years.”

My colleague smiled. “My father lived the wrong life, you see, yet I am the product of that wrong life.”

The candor with which he described his father’s life disturbed me. Was there such a thing as a wrong life? I asked.

He looked at me. Yes, there was, he said, and went no further. But if I was interested in reading about misspent lives, he added, perhaps I should pick up W. G. Sebald.

This was the first time I’d ever heard of Sebald. Had it not been for that car ride that evening, or for that conversation about my colleague’s father, chances are I would have discovered Sebald under entirely different circumstances and, in light of these circumstances, read him in a very different way.

I bought The Emigrants that same evening at the Barnes & Noble on the Upper West Side. Most people read Sebald in light of the Holocaust. I read him in the key of misspent lives.

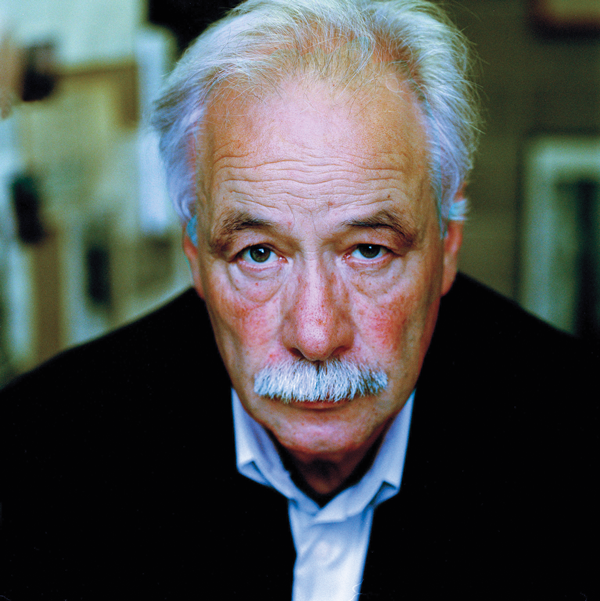

Sebald at his office at the University of East Anglia, shortly before he died in 2001. So much of his work concerns “lives that have been cast adrift, unlived.” (Eamonn McCabe)

Sebald at his office at the University of East Anglia, shortly before he died in 2001. So much of his work concerns “lives that have been cast adrift, unlived.” (Eamonn McCabe)

On finishing The Emigrants a few days later, I could not stop thinking of the last of the four tales that make up the book, each devoted to a single character. Here, the grown Max Ferber, who was shipped off to Manchester from Germany as a boy without his parents, has led a relatively successful life as an artist in England but is permanently scarred by what the Nazis had done to his mother. Life after the Holocaust was, as the French call it, not a vie, but a survie—not living, but surviving. The road originally intended was never traveled. What took its place was a makeshift path, which one would still have to call life, and maybe even a good life, but it was never going to be the real life. Cut short, this might-have-been life didn’t necessarily die or wither; it just lingered there, always unlived and beckoning. Stumps don’t always die, but they no longer thrive; the offshoots do the work of the tree.

The parallels between my colleague’s father and Max Ferber were no less compelling. Both men ended up living lives that always felt partially misspent: one with the wrong spouse, the other in the wrong country, speaking the wrong language, among the wrong people. Both made the best of what they were given. But the similarities with Sebald’s characters and his own life are equally striking. Sebald was himself a German who had been living and teaching university in England since the 1960s—not an exile but an expatriate who, in so many intangible ways, remained a displaced soul. He was not Jewish, but he seemed to write about individuals who were Jewish or had close ties to those Jews whose lives had been thrown off course by the war, loss, horror, exile, or, to use Sebald’s term, mere transplantation. So much so, that it was no longer clear to them not just where, or why, but how exactly they belonged on this loose bolide called planet Earth, or whether belongingheit could ever be applied to them again, because this too was true: they had no notion of where they stood vis-à-vis this ungraspable other thing called time. Was time fast-forwarding or turning back on them, or was it simply standing still, year after year after year, until it ran out? Or, to look at things differently, were they out of step with time, because time’s covenants, to use T. S. Eliot’s term, no longer held for them? These survivors, too, looked out of windows with despair and melancholy in their eyes, wearing that glazed and vacant stare that tells you that although still alive, they have in fact already died. They’re not ghosts, but they are not of us. “And so they are ever returning to us, the dead,” Sebald writes—words he repeats in one way or another in almost all of his books. It bespeaks his inability to understand how porous is the membrane between what might have been and might yet be, between how things never go away but aren’t coming back either, between life and that other thing we don’t know the first thing about. As Jacques Austerlitz in Sebald’s novel Austerlitz says,

I feel more and more as if time did not exist at all, only various spaces interlocking

according to the rules of a higher form of stereometry, between which the living and the dead can move back and forth as they like, and the longer I think about it the more it seems to me that we who are still alive are unreal in the eyes of the dead, that only occasionally, in certain lights and atmospheric conditions, do we appear in their field of vision. As far back as I can remember … I have always felt as if I had no place in reality, as if I were not there at all.

It was not Max Ferber, however, but another character in The Emigrants, Dr. Henry Selwyn, who ignited something in my mind, and whose mesmerizing tale left a lasting impression on me. Here, the narrator remembers that years earlier, in 1970, he had befriended his English landlord Dr. Henry Selwyn and that, in the course of several conversations, the landlord had managed to reveal a number of facts about his earlier life: how, contrary to appearances, he was really not a Briton but a Lithuanian whose family had emigrated to England in 1899 when he was seven years old; how the ship on which the family sailed had ended up not in America, where it was originally destined to sail, but, by accident, in England; how, growing up in England, young Selwyn had felt the need to conceal his Jewish identity from everyone, including, for a while, his wife, from whom he is essentially estranged, though they continue to live under the same roof; and how, as a young man in 1913, he had met a 65-year-old Swiss mountain guide named Johannes Naegeli. This mountain guide died soon after Selwyn returned to England at the start of World War I and “was assumed … [to have] fallen into a crevasse in the Aare glacier.” Young Selwyn, fighting on the British side, was devastated by the news of Naegeli’s disappearance, for he seemed to have been exceptionally fond of the older man. Fifty-seven years later, in 1970, Selwyn tells his tenant, “It was as if I were buried under snow and ice.”

If the plot of this short story remains irreducibly simple, the situation grows increasingly complex when it becomes clear that the story is built on highly unstable plates representing different periods of time hurtling against each other like blocks of glacial debris. At one moment, one of these temporal plates may be buried deep underneath all the others; at another it bursts forth and buries everything else. Fifty-seven years later, the subject of the mountain guide suddenly erupts in the course of a dinner conversation; the guide, it would seem, is far more alive to Selwyn now than is his wife who shares his home.

Three aspects struck me in this story.

First, the Holocaust. Selwyn’s accidental migration to England took place long before the Holocaust, and therefore the Holocaust, as it affects Selwyn or his relatives in England, is irrelevant—except that the Holocaust, which hovers over the other three tales of The Emigrants, suddenly begins to cast a retrospective shadow over Selwyn’s tale and by implication over his entire life. It is as if the Holocaust were not absent from his life but was simply overlooked, as if it had been hinted at all along but we as readers had just failed to notice, because Selwyn as a character never quite sees things in light of the Holocaust either, because Sebald himself had never put the pieces together until he’d written the other three tales. To echo Selwyn’s own words, it is all as though the Holocaust were buried under ice, and no one sees it. The Holocaust is never brought up once in this first tale.

If Jacques Austerlitz eventually finds out that he is Jewish and, like Ferber, had arrived in England via Kindertransport, in The Emigrants no amnesia delays the discovery of Selwyn’s Jewish roots. Sebald simply does not mention his Jewishness except almost as an inadvertent aside, a slip. And yet the whole tale is written in the retrospective key of the Holocaust.

I look for hints of what happened in Selwyn’s life during World War II, but the subject has been perfectly elided and screened off; I comb the text for what it does not say, will not say, refuses to say, is too timid or too repressed or scared to say, but find nary a clue. Anyone seeing a film set in 1932 Berlin will automatically be filled with disquieting forebodings when watching two Jewish lovers kissing debonairly in a secluded spot in the Tiergarten. Something is about to happen or may indeed not happen to them, but watching the lovers without intimations of what lies ahead makes no sense and is critically flawed. The viewer nurses these disturbing feelings because he watches the goings-on of the lovers prospectively—and the film director, naturally, and without even suggesting the Holocaust, exploits and stokes these misgivings. Along the same lines, it is impossible today to read or say anything about Irène Némirovsky, the sharp-eyed, supremely Gallic novelist—born in Kiev and dead at Auschwitz—without invoking retrospectively the Holocaust.

Selwyn may have escaped the Holocaust, but on closing all four tales of The Emigrants, we sense that he lives with the “memory” of this event that never happened to him but would more than likely have happened had he never left Lithuania in 1899 as a child. But far, far more uncannily yet, we also feel that the Holocaust, despite his move to England, is not necessarily done with him. Retrospectively, the Shoah could come to exact its due in good time, for there is no statute of limitations on what hasn’t happened—and besides, the Shoah is in no hurry. This is not about past and present and future, but about what grammarians call irrealis time. It’s not about what did not or will not occur, but about what could still but might never occur. If time exists at all, it operates on several planes simultaneously where foresight and hindsight, prospection and retrospection are continuously coincident.

Selwyn was spared by accident; history could easily decide to rectify the mistake. Something that never happened and couldn’t have happened to him and had altogether stopped happening 30 years earlier continues to radiate, to pulsate, to reach into the 1970s like a defunct star millions of light years away whose light is still traveling in outer space and hasn’t even reached our beloved planet Earth yet.

This is not about the Holocaust happening all over again in the late 20th century; it is not about facts, or even about speculative facts, but about counterfactual—that is, irrealis—facts. It is about turning the clock back to 1899 while simultaneously living in the late 20th century. How historians explain time is one thing, but how we live time is quite another.

Freud understood this kind of counterfactual mechanism when he realized that with screen memories “there was no childhood memory, but only a phantasy put back into childhood.” The later intrudes upon the earlier. The later alters the earlier. The later and the earlier trade places. There is no earlier or later. There is no then and now.

The second striking aspect of Sebald’s tale is the failed migration to America. The promise of settling in New York was never realized for the Selwyns. They settled in England, made the best of things, and indeed prospered, but their prospective life in New York was neither realized nor expunged from their imagination. For them, even if they are dead now, things are still being worked out on some sort of parallel time warp, and the ship that made the mistaken stop in England may still eventually decide to leave England and cross the Atlantic with young Selwyn and his family aboard, even if he’s much older now than were his parents at the time, even if their ship ended up in a scrap-metal junkyard before the Second World War. The voyage out feels like a promissory note that has yet to come due but will never come due, like those bonds sold by the Tran-Siberian Railway Company at the turn of the 19th century that you can still buy for next to nothing at the stall of any bouquiniste along the Seine in Paris: these bonds are very real, but they cannot be realized. They have become irrealis bonds, the way their bearers are irrealis people, the way the voyage to America is irrealis, the way the Holocaust and its impact have no time markers and are therefore free floating on the spectrum of time.

And here lies the real tragedy. The dead don’t just die. Death may not be the ultimate undoing. There is an after omega. And it may be worse. “It truly seemed to me, and still does, as if the dead were coming back or as if we were on the point of joining them,” the narrator of the “Paul Bereyter” section of The Emigrants says. “We have already died once,” says the father of Göran Rosenberg, whose book A Brief Stop on the Road From Auschwitz describes an attempt to begin a new life after the Holocaust. But the rebirth, as the rebirth of the writers Paul Celan, Primo Levi, Bruno Bettelheim, Tadeusz Borowski, and Jean Améry proved to be, isn’t worth the price. Survival is too costly. In their case, the implacable Shoah has a persistent long reach and there are things that are worse than death. For what the Shoah does if it doesn’t kill you the first time around is to utterly demolish, in the words of Améry, your trust in the world. Without trust in the world, you are, like the dead, simply hovering in the twilight. There is no place to call home, and you will always keep getting off at the wrong station on the long road from Auschwitz, from Lithuania, or from wherever you came.

Sebald’s narrator in The Emigrants is deliberately silent on the subject of the Holocaust, just as he is opaque about the failed voyage to New York. I have no sense of why that is, and wonder if I may not be pushing my reading of this story. What becomes clear, once you collapse the book’s tales and have laid out the names of the temporal plates like suspects on a police station bulletin board, is that language lacks the correct verbal tense or the correct mood to convey the haunting and unwieldy counterfactual reality of a might have been that never really happened but isn’t unreal for not happening and might still happen though we know it cannot.

This is the very cynosure of counterfactual thinking. Call it retro-prospection collapsed into a single and unthinkable gesture. In the language of water dowsers, it is about water that may or may not be underground, that may have dried up or may be welling up, or both at the same time—water always working its way to the surface or disappearing farther underground. Dowsers call this phenomenon remanence: the retention of residual magnetism on an object long after the magnet force has been removed, the memory of water in the soil, the retention of so many emotions long after their cause is removed and possibly forgotten.

It is the script on the roads not taken and on lives that have been cast adrift, unlived, or misspent and are now marooned in space and time. The life we’re still owed or that fate dangles before us and that we project at every turn and feed upon and, like a virus or a suppressed gene, that gets passed on from one day to the other, from person to person, from one generation to the next, from author to reader, from memory to fiction, from time to desire and back to memory, fiction, and desire, and that never goes away because the life we’re still owed and cannot live transcends and outlasts everything, because it is part yearned for, part remembered, and part imagined, and it cannot die and it cannot go away because it never ever really was.

This script is ultimately what we leave behind, what still remains and still pulsates after we stop breathing—our Nachlass in time, our unfinished business, our ledgers left open, our accounts receivable, our unrealized fantasies and unlived minutes, the conversations still on hold, the unclaimed luggage in the cloakroom still holding out for us long after we’re gone for good.

This is Sebald’s universe. Supremely tactful, Sebald never brings up the Holocaust. The reader, meanwhile, can think of nothing else. Sebald barely mentions the accidental move to England, but I have no doubt that Selwyn has been living not just the unintended life, or the accidental life, but also the wrong life. The life he lives contends with a counterfactual life occurring in some sort of nebular, spectral, irrealis zone. This sense of having mislaid one’s true life, one’s real self, is finally formulated in Austerlitz, when the eponymous character tells the narrator: “At some time in the past, I thought, I must have made a mistake, and now I am living the wrong life.”

People may take their own lives when they realize they’ve been living the wrong life; or, as is the case with people whose lives have been devastated by loss and tragedy, they may outlive the course of their years precisely because they’re clinging on to encounter the life they’re still owed.

Hardly surprising, then, that while vacationing in France, Selwyn’s former tenant should hear that the good old doctor had finally closed the ledger and shot himself.

And here comes the third baffling aspect of Sebald’s tale. Selwyn’s business is by no means over even after he dies. In 1986, as the narrator is traveling by train through Switzerland, he begins to remember Selwyn. And as he thinks of Selwyn, he accidentally—actually, the adverb should be coincidentally—spots an article in that day’s newspaper reporting, Sebald writes, that “the remains of the Bernese alpine guide Johannes Naegeli, missing since summer 1914, had been released by the Oberaar glacier, seventy-two years later.”

The body that was lost during the summer of 1914, moments before World War I, has finally worked its way up to the surface, long after the war has become a hazy memory, long after its dead have decomposed, long after the bodies of those who lived through that war only to perish in the Holocaust have completely disappeared. No one who was old enough to be a soldier in 1914 is alive today, yet suddenly the frozen, undecomposed body of Johannes Naegeli is younger than Henry Selwyn, himself dead for 26 years now. When Rip Van Winkle returns, he is not only an anachronism, he also has every reason to believe, unless he looks in a mirror, that he is 20 years younger than those of his own generation. Meanwhile, Sebald’s narrator would have loved nothing better than to show the newspaper article to Henry Selwyn, to allow the older doctor to come to a reckoning with his younger self. But therein lies the stunning cruelty of time. A reconciliation, which would in theory have straightened so many things, cannot take place. Reconciliation, reckoning, reparation, restoration, redemption—these are, at best, paltry figures of speech—words—as are the concepts of “unfinished business” and “open ledgers” and being “indefinitely put on hold.” Time has no use for such words. Because no matter how crafty our grammarians are, we still don’t know how to think of time. Because time doesn’t really understand time the way we do. Because time couldn’t care less how we think of time. Because time is just a limp and rickety metaphor for how we think about life. Because ultimately it isn’t time that is wrong for us. Neither, for that matter, is it place that is ineradicably wrong. Life itself is wrong.