Terrorism is as old as recorded history. Plutarch describes how ancient Spartans would ambush and kill a few enslaved helots every year to keep the rest in a state of terror. A few centuries later, according to Josephus, the Jewish Zealots earned the moniker sicarii, or dagger men, thanks to their practice of slitting the throats of Roman officials in crowded marketplaces. The dagger was also the weapon of choice for the Assassins, a medieval Shiite sect dedicated to the destruction of both the Sunnis and the Crusaders. For more than a millennium, a Hindu offshoot known as the Thuggees strangled unsuspected travelers as offerings to the goddess Kali.

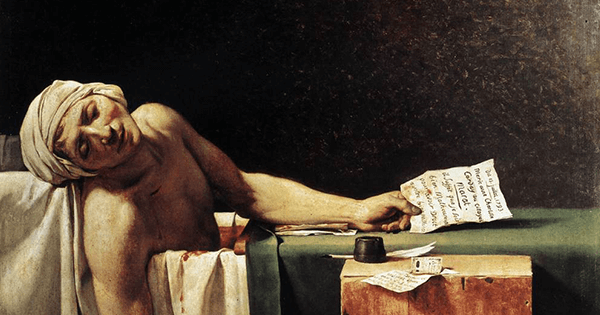

Fast forward to the modern age, when the French Revolution ushered in a century and a half of guillotines, gulags, and gas chambers. The defining trait of totalitarian states ever since, from Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy to Communist Russia and China, has been the systematic and sustained use of terror to maintain power. Whether used by states that capitalize on violence and repression, or by stateless movements that monopolize the attention of our media and governments (and justify wars), terror remains the order of the day.

Historians and sociologists, philosophers and political theorists have interpreted terrorism, adding a great deal to our knowledge, but less to our understanding. For the latter, perhaps we need to turn to novelists. Who better, really, to convey what Henry James called the “picture of the exposed and entangled state” of human events? And so, here is a short list of Western novels (along with a play and one work of nonfiction) on this bleak subject. Though most of these works deal with the long 20th century—stretching from the rash of nihilism and anarchism to the emergence of jihadism—they all speak to the awful timelessness of terrorism.

Ivan Turgenev, Fathers and Son

In Yevgeny Bazarov, Turgenev gave flesh and blood to the term “nihilist.” Published in 1862, the novel recounts the final months of Bazarov’s short and stunning life. He rebels against the deadweight of the Tsarist state by rejecting all of society’s values and ideals. “We repudiate,” Bazarov declares, “everything.” As for what should be built in its place, he shrugs: “That is not our affair … the ground must be cleared first.”

Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Possessed

Unlike his contemporary Turgenev, whose conflicting cosmopolitan manners and liberal politics drove him mad, Dostoevsky had firsthand knowledge of the terrorist mind. Imprisoned and sentenced to death in 1849 for participating in a revolutionary student group, he underwent a mock execution before being exiled to Siberia for several years—experiences that forever shaped his worldview. In The Possessed, Dostoevsky takes strands from a recent event—a few aspiring nihilists who, incited by their leader Sergey Nechayev, murder one of their own members—and weaves a tale of murderous mayhem on behalf of a dire ideal: “wholehearted destruction, continuous, unflagging, unslackening, until none of the existing social forms remains to be destroyed.”

Emile Zola, Germinal

Set during a miners’ strike in northern France, Zola’s novel teems with a cast of thousands: doomed lovers, evil capitalists, frenzied women, stout men, and a drowning horse. But it is Souvarine, the character who sets in motion the story’s tragic dénouement—he dynamites the mine while it is filled with miners—who is the most unsettling and unyielding. A Russian immigrant steeped in anarchist theory, Souvarine scorns the striking miners as much as he does the mine’s owners. When the novel’s hero, Étienne Lantier, asks him what he wants, Souvarine—dreamily pulling on a cigarette while stroking the fur of a pet rabbit—replies: “to destroy everything.”

Joseph Conrad, The Secret Agent

“The most ardent of revolutionaries,” Conrad wrote, “are perhaps doing no more but seeking for peace in common with the rest of mankind—the peace of soothed vanity, of satisfied appetites, or perhaps of appeased conscience.” This observation lies at the heart of The Secret Agent, based on the actual attempted bombing of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich in 1894. Placing this act in the dark milieu of foreign and native anarchists who had made London their home, Conrad created the memorable character of The Professor. Embittered by professional failure, The Professor supplies explosive material to all those dedicated to the destruction of the society that rejected him. “What happens to us as individuals,” he tells one associate, “is not of the least consequence.”

Joseph Conrad, Under Western Eyes

Under Western Eyes moves what Conrad calls the “terroristic wilderness” from the grimy slums of London to the bourgeois dullness of Geneva, home to a large and motley crew of revolutionary pamphleteers and bomb-makers, true believers and opportunists. In a note, Conrad observed how the “ferocity and imbecility of an autocratic rule … provokes the no less imbecile and ferocious answer of a purely Utopian revolutionism encompassing destruction by the first means to hand.” A century later, this observation serves as an epitaph for many Middle Eastern states and their jihadist progeny.

Albert Camus, The Just Assassins (Les Justes)

In 1905, Ivan Kaliayev, a young Russian student, assassinated the Grand Duke Sergei. But in Camus’ dramatic restaging of the event, Kaliayev and his fellow conspirators are terrorists unlike any other: they debate and agonize over their vocation. Though they limit their targets to Czarist officials, their doubts persist. But even their scruples, Camus suggests, do not absolve them of guilt. As he declared in his essay “The Rebel” our task is “to refute legitimate murder and assign a clear limit to its demented enterprises.”

Don DeLillo, Mao II

DeLillo’s novel captures the decisive role the crowd plays in our postmodern age—both as consumer and something to be consumed. A reclusive novelist, Bill Gray, finds himself drawn into a terrorist plot in the Middle East. There is, he realizes, a “curious knot that binds novelists and terrorists.” The latter had taken over the former’s traditional role in shaping and influencing minds. “Years ago I used to think it was possible for a novelist to alter the inner life of the culture. Now bomb-makers and gunmen have taken that territory. They make raids on human consciousness.”

Hilary Mantel, A Place of Greater Safety

On September 5, 1793, when France’s revolutionary National Convention announced terror was “the order of the day,” the modern age tilted on its axis. For the first, and far from the last time in history, a state had claimed terrorism as a tool of governance. While the revolutionaries’ justification for terror was reason—or, rather, Reason—and not religion, its character was as merciless and millenarian as the Crusades and the Inquisition. Long before she turned to the sporadic terror that marked Henry VIII’s reign in Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies, Mantel explored the nature of revolutionary terror with a Robespierre who is both tragic and terrifying.

Lawrence Wright, The Looming Tower

Wright’s history of the rise of Al-Qaeda and fall of the World Trade Center is not a novel, but it reads like the best of them. Thickened by hundreds of interviews, visits to key countries, and piles of primary sources, The Looming Tower has the same narrative tension and indelibly sketched characters as Balzac’s Human Comedy. Just as Balzac claimed to write the history of early 19th-century France, Wright has written the history of late 20th-century America and its role in the creation of a dizzying maze of international terrorism.

Michel Houellebecq, Submission

History rarely has shown itself more cunning: Houellebecq’s novel was released in France on the very day—January 7, 2015—that Islamist jihadists attacked the offices of Charlie Hebdo and a Jewish supermarket. The novel, set in 2012, imagines a dystopic future in which the right-wing Marine Le Pen vies with a Muslim contender for the presidency—and loses. Submission’s dizzying success derives, in part, from the great unease that many French feel about the place of Islam—an unease that will only deepen, and a scenario that will only become more plausible, due to the terrorist attacks that have since followed.