The Millionaire and the Bard: Henry Folger’s Obsessive Hunt for Shakespeare’s First Folio, by Andrea Mays, Simon & Schuster, 350 pp., $27

Henry Clay Folger (1857–1929) operated under the radar long before there was radar. Together with his wife, Emily, who shared his reverence for the Bard, he quietly assembled the collection that later formed the nucleus of the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C. The couple sought no biographer; the words chiseled above Christopher Wren’s tomb in St. Paul’s Cathedral fit them just as well: Lector, si monumentum requires, circumspice (“Reader, if you seek his monument, look around you.”). But recently, two authors have tried to hunt down this elusive prey.

In his assiduous yet accessible Collecting Shakespeare: The Story of Henry and Emily Folger, published last year, Stephen H. Grant offers a thorough account of the lives, collecting practices, and philanthropic goals of this austere, dedicated couple. Their financial records and correspondence with booksellers and agents provide glimpses of a close, purposeful marriage. Yet a kind of Yankee reticence obscures their inner lives. Grant nevertheless manages to show how these passionate Shakespeareans, working together without curators and advisers, competed effectively against far wealthier collectors.

Folger, a company lawyer who rose through the ranks to the presidency and then the chairmanship of the Standard Oil Company of New York, came from modest circumstances and had no interest in the trappings of wealth and power. Aside from his great loyalty to the firm and its founder, John D. Rockefeller, he cared exclusively for his wife and for Shakespeare, whom the couple saw as the most complete embodiment of America’s English heritage. Grant traces the evolution of their thinking and planning, from their early days as young collectors through their major acquisitions in the first and second decades of the 20th century, to the planning and creation of the great library that bears their name.

Now comes The Millionaire and the Bard. Andrea Mays, a lecturer in economics at the California State University at Long Beach, views Folger as a classic obsessive, driven to accumulate a “hoard”—the word is recurrent—of copies of the First Folio of Shakespeare’s plays. A successful business executive in the age of the robber barons, Folger, as she sees it, in both his vocation and his avocation was motivated by greed, a deep-seated psychological need to possess the objects of his interest. Consumed by this irrational impulse, she argues, Folger let nothing stand in his way.

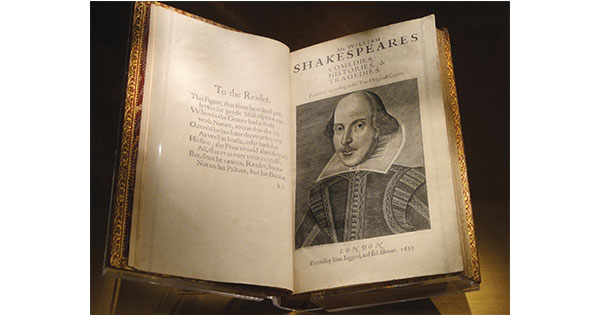

Mays organizes much of her book around the Folgers’ quest for multiple copies of the First Folio, the volume of Shakespeare’s plays published in 1623 by two members of his acting company. On the face of it, it seems puzzling that he would have felt a need to corner the market for this iconic book. Yet year after year and with great success, Folger sought to buy every copy he could find, including those that he and his agents, through persuasive letters and even personal visits, attempted to dislodge from owners often reluctant to sell. Strange, too, is that Folger was not a bibliophile. He had no particular interest in binding, provenance, condition, or any of the other aesthetic concerns that motivate most book collectors. Extremely price conscious, he would happily buy an inferior copy of a book that a scholar might someday want to consult, even if a fine one was readily available.

The Folgers bought First Folios regardless of their completeness, condition, or provenance, eventually ending up with 82 of the approximately 244 surviving copies. They were content to acquire fragments, individual plays, even odd sheets. Of one folio purchase, Mays remarks, “Only a man in Shakespeare’s thrall could have cherished this shabby relic.” That volume, therefore, like dozens of others, she sees as proof positive of Folger’s obsessiveness. She even compares him to the notorious Collyer brothers, found dead in their Harlem apartment in 1947 along with 180 tons of possessions. But to make the charge stick, Mays has to play down the reason the Folgers wanted all those copies, including very defective ones, of a not particularly rare book. She lets it slip a few times, though the reader might be forgiven for missing it amid her numerous characterizations of the Folgers’ senseless hoarding: the Folgers believed that a comprehensive study of the typographical variants in individual copies of the First Folio would reveal Shakespeare’s true intentions. Hence, in an era before widespread copying technology, it made sense to bring multiple copies together in a single location. The Folgers turned out to be mistaken about this, but there was method, not madness, in the quest.

Mays nevertheless asks us to believe that Folger “led a double life.” She places him within “the spectrum of sanity” (thanks!) but writes that “like Faust, he was a prisoner of a notion not his own.” For Mays, Folger belongs in the company of “other famous American pack rats.” Despite her attempts to cut Folger down to size, she can’t help admiring his achievement. In fact, Mays exaggerates it in stating, for example, that he left a collection of 256,000 books— a number that approximates the current size of the holdings after another 83 years of collecting by his library.

In her unwavering focus on Henry Folger’s supposed psychological motivation, Mays misses out on much of what Grant develops with sensitivity and insight—the remarkable and productive partnership between “the millionaire” (he was not always thus) and his learned and accomplished wife. For decades, they sat opposite each other at a partners’ desk as they opened the packages that poured in to their modest Brooklyn apartment. They had no children, but time and again, the literary and visual embodiments of Shakespeare, swaddled in tissue paper, cardboard, and twine, emerged into the world between them. No other ménage à trois has produced a comparable legacy.