In the first episode of the TV series In Treatment, which aired on HBO from 2008 to 2010, a young woman named Laura tells her analyst how she met a stranger at a club the previous night and how, after a few drinks, the two of them headed to a bathroom stall, intent on a hasty hookup. What she and the man needed from each other was plain enough, and she spares the analyst none of the details: the man’s erect penis, the exchange of fluids, the sound of a man peeing in the next stall, and so on. Physical contact, casual or not, hardly scares the stunning-looking Laura. She can have any man she wants and knows it, which might perhaps explain why her relationship with her current boyfriend is on the rocks. Laura (played by Melissa George) is bold, frank, unabashed, and savvy enough to ask her therapist (Gabriel Byrne) whether her late-night episode in the stall repels him or turns him on. Though the bathroom encounter was a first for her, she then tells her analyst that he should not be shocked, since she has been unfaithful to her boyfriend for a whole year. Taken aback by the revelation, the therapist wonders why she had never mentioned this other lover during all of their previous sessions. “I think we have,” she replies, staring intensely in his face during an awkwardly long silence. “It’s been here all along.” The girl who had been quite voluble with the minutiae of bathroom sex suddenly begins to speak in riddles.

“I don’t follow what you mean,” says the therapist, seemingly stumped.

“You mean you don’t know?” No, he doesn’t know who this other man is, he replies. Finally, still gazing, she tells him: “It’s you. I’m in love with you.”

“Since when?”

“Since our very first session a year ago.”

In the Italian version, when confiding this, Laura changes from using the formal Lei form of address to the informal, more intimate tu. But this change of pronouns hardly shatters the wall between them.

It took Laura a year to let out her secret. She can confide the sordid details of physical contact, but speaking about what sits between her and her therapist is an entirely different affair and requires all manner of hesitation, innuendo, and subterfuge. Her admission may represent a groundbreaking moment in her psychotherapy, but it comes at a cost: from this there is no turning back. Which may be why she can’t keep herself from weeping as she clutches paper tissue after paper tissue while confessing the secret she has been cradling during an entire year. She experiences the terrifying thrill of finally letting down her guard, but she is also cast in the role of a dismayed, hapless, and vulnerable child who has no way of knowing whether the man she’s confiding in will embrace her or turn her out. She would have preferred a hug, but weeping is as physical as things get in this therapist’s office. What exists between them during this unnerving session is silence and speech, and both are unbearable and both leave her scuttled and totally bereft. “What will I do now? Where will I go?” she asks after her confession.

A passionate kiss would, of course, have defused the uneasy ambiguity in the shrink’s office. After all, it may be that, despite his professional conduct, the therapist feels no differently than she does. But a kiss is not an option, even if a first kiss after a disconsolate avowal like Laura’s is what happens in almost every film. Caught in the unforeseen lull, lovers in films fall silent, stare meaningfully into each other’s eyes, and in a tremulous crescendo, let go of whatever held them back and kiss. Such a moment cannot be planned or rehearsed; it needs to spring on them. Once their lips near, nothing can stop them. Qualms, doubts, shyness, and fears are brushed aside. This is when speech must unavoidably yield to passion. Talking about the kiss before it happens would ruin the spell and kill the surge of tension and desire. Silence must always trump speech, and the lovers must swoon into their kiss.

But the swoon is also how the lovers avoid asking many questions. How they feel, what they want, why their lives suddenly seem to hang on this moment, and what strange turn of events brought them to this pass—all these are summarily answered by the kiss. It is always much easier to initiate the first kiss than to ride through the terrifying silence that precedes it. More difficult yet is talking about desire without the option of swooning into it. Or Laura might love this moment between them more than she loves him. That she can finally unburden herself and speak to him about a love she believes is hopeless may be more important to her than any physical or emotional fulfillment.

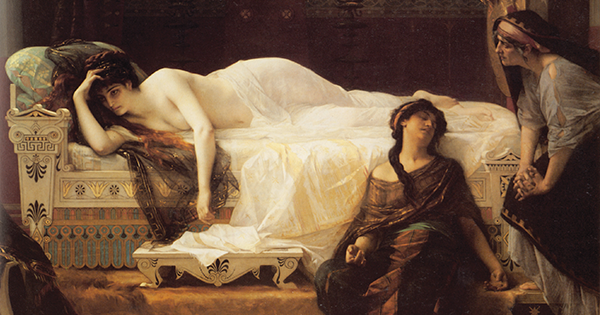

Enter Phaedra, wife of King Theseus and stepmother to Theseus’s son, Hippolytus. Phaedra is consumed by her love for Hippolytus but knows that what barely keeps her smoldering passion from erupting in full view is the guilt and shame of both incest and adultery. Meanwhile, depending on which version one reads, Hippolytus is either in love with someone else or sworn to chastity and is as horrified by his stepmother’s crime as is Oedipus on finding he has slept with his birth mother, Jocasta. For Phaedra, kissing Hippolytus is not an option. She must speak her passion. The risks are enormous—and tragic.

In Euripides’s Hippolytus, Phaedra confesses her love to her nurse, who then relays it to Hippolytus. As expected, Hippolytus is appalled by what he hears from the nurse and rushes out. In Seneca’s Phaedra, things are more complex and may be based on another version of Euripides’s Hippolytus that is no longer extant. Phaedra first swoons, then begins to open up to the man she craves but speaks too haltingly, unable to say what she means:

The words start, but my mouth won’t let them pass.

A great force prompts my voice; a greater force

restrains it. Powers of heaven, I testify

before you: what I want I do not want.

Ingenuously, he prods her as would any therapist and urges her to tell him what troubles her. “Your mind desires something but cannot speak?” he asks, adding, “Trust your anxieties to me, mother.”

Finally, out comes her veiled, impassioned outburst. “Hippolytus, this then is how it is.” By virtue of not particularly delicate innuendos, she allows him to infer that it is he, Hippolytus, she loves, not Theseus, his father. Seeing his failure to react, she kneels before him: “Pity my love,” which is when he finally voices his horror and outrage.

But it is Racine’s Phèdre that allows us to sense how unsparingly difficult are avowals and how devastating their consequences. The French have a name for such a scene: la scène de l’aveu. Avowal is the irreversible denudement of one’s own identity; it leaves one crushed, humbled, and defenseless. Mustering the strength to speak one’s heart may demand the ultimate in love but also the ultimate in daring. Swooning is out of the question; between Phèdre and Hippolyte lies a scary ravine, and the suspense and shame are unbearable.

At first, Hippolyte is so unsettled by Phèdre’s declaration that he is convinced he must have misunderstood her, and he apologizes for giving her declaration a totally inappropriate spin. But Phèdre has gone too far to backtrack. With nothing left to lose, she lets him have it: “Know, then, Phèdre in all her fury!” she cries. One can forgive the loss of love, but loss of face is deadlier business. From the decorum of exchanges between Madame Phèdre and Seigneur Hippolyte, Phèdre resorts to the familiar tu pronoun, an insolent tu, a lover’s tu.

Phèdre’s avowal is not an opening, not a desperate pass at the person desired. It is an advance that already slams the door on words she at first has a good mind to take back. Such advances anticipate the worst. Phèdre’s avowal in Racine is hostile, toxic; it’s not a caress, it’s a curse. The actress in In Treatment is really saying: I love you, but please tell me it’s hopeless. Her shameless, in-your-face advances, both persuasive and seductive, cry out their despair, braided in anger and spite like love bites from Lady Macbeth.

What happens in the 1962 film version of Phaedra, directed by Jules Dassin, is thin gruel. At some point, Phaedra (played by Melina Mercouri) will tell Alexis, the Hippolytus figure (Anthony Perkins), that she loves him. Since stepson and stepmother haven’t been getting along, when she says, “I love you,” he is convinced she is mouthing a mere platitude and replies with a chill “Thank you.” She corrects him by saying, “I am in love with you.” No sooner said than they begin kissing and swooning. The protracted Phaedra moment belongs to another play.

But the movie gets one thing right: as in the television series, Hippolytus here—the therapist—may very well be in love with Phaedra. But this is not relevant. What is relevant is that the ever-protracted distance between them needs to remain insuperable.

In any work of art, whether a film, a play, a novel, or a painting, physical contact is how lovers eventually reveal their desire for each other. The hand that reaches out and holds another’s, the caress, the knees that touch, the elbows that happen to meet but then linger and won’t withdraw—this is what happens when two humans bridge the distance separating them. It reminds us that the entire history of mankind, and of human sexuality in particular, is nothing more than the chronicle of beings struggling to breach the distance between them. The social impediments may be daunting, but one way or another they are overcome. Either one is accepted, or one is rejected.

But in In Treatment, the therapist is a cypher, and because of his professional constraints, both he and his patient are trapped. If he wishes to fly away, he cannot: he’s her doctor. If she wishes to take things to the next step, she cannot: she’s his patient. They keep drawing closer and closer until it becomes obvious that theirs is an eternal asymptote of missed embraces, missed moments, missed opportunities. All of their impulses are frozen. As Laura says, every Monday she walks into her analyst’s office having resolved to speak her love and yet every Monday she leaves crestfallen, knowing she has yet again failed to keep her resolve. She will have to live an entire week now with harrowing reminders of that failure and with the flimsy hope of mustering the very resolve she already fears will elude her the following week.

It is a sign of a successful talking cure if Laura finally blurts out her secret. That she is in love with her therapist is a telltale sign of transference. What keeps the tension taut is not the time needed for the ice between them to melt but the perpetual tussle between transference and counter-transference. Everyone knows that, however much he denies it, the therapist is at least as much in love with Laura as she believes she is with him. Everyone also fears the worst: that the moment he lets down his guard she will lose interest. Yet we see enough to want them to move forward; they see enough to know that they will regret it. What keeps the whole thing going is not the gradual, unavoidable emergence of the truth but its perpetual deferral, its perpetual obstruction. This may not be good therapy. But it is great television.