The Viewing, Summer 1909, Constantinople

My grandfather walks down the long corridor to the room where Maria and the other two girls he has purchased are waiting to be viewed. Maria has not seen the other girls before; they are both 15, like she is. They have been brought from across the border in Batum, and like her, they have each been sequestered in a separate room for a week before this final viewing that will decide their fates.

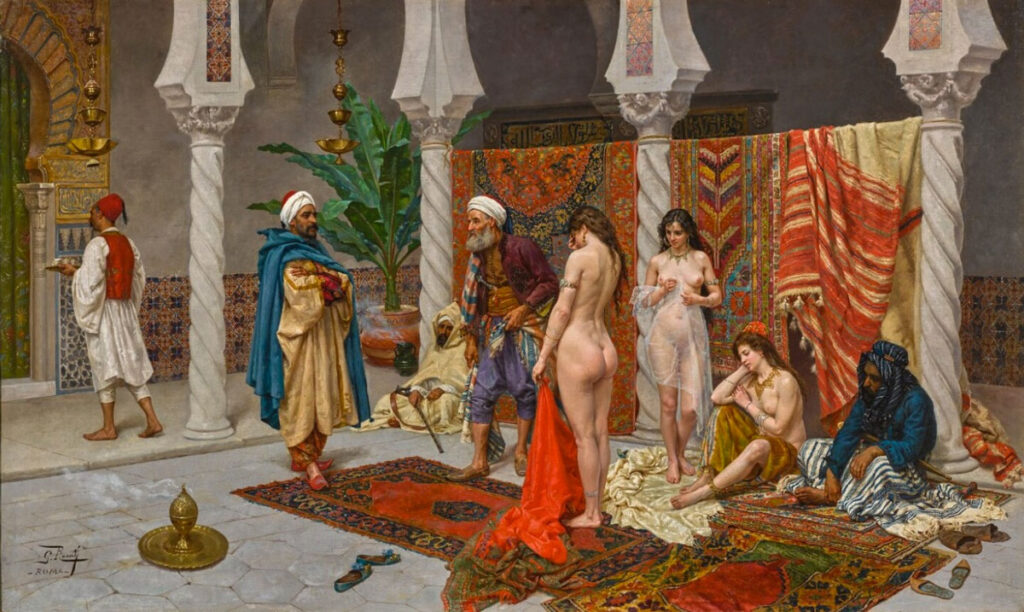

Despite the warm afternoon, my grandfather is in formal attire, a monocle that glints in the light, and white gloves fine enough for his rings to fit over the fingers. He is both a modern Ottoman and a conservative Muslim, so he considers the choosing of girls for his household a solemn occasion. It is now to be seen whether the girls will please him enough to stay on as concubines, please him only mildly and stay on as servants, or please him not at all and be sent away to be sold to other households. By the time my grandmother Maria entered his home, my grandfather had been purchasing girls for over 30 years, and during this time a fixed protocol had evolved. He and his first wife, Grandmother Zekiyé, whom he married when he was 20 and she was 16, review the girls together, each with a different set of priorities. Grandfather looks for beauty, grace, European features, a lean-but-busty line, a natural demureness, and what he calls a many-pronged wit—once a girl is accepted into his household as a concubine, she is there to stay, and within a decade her wit might be her only recourse against the fading of her charms. Grandmother Zekiyé views the purchased girls through a narrower prism: her eye probes torsos and thighs in search of imperfections a man might not immediately notice. If a girl is to be resold, it will have to be before Grandfather takes her virginity, so Zekiyé looks for any flaws that might dampen his interest after his initial excitement pales. She also has a knack for evaluating the durability of a teenage breast, chin, or hip. Slim at 13 does not mean slim at 18; one chin can turn into three. A girl might be prone to pimples, which is acceptable, even charming, but only if the pimples are not the kind that leave blemishes.

An equally important purpose of Zekiyé’s inspection is to determine if a girl will fit into the inflexible hierarchy of the household. Is the newcomer a quick learner, clever enough to acquire elegant Turkish? Will she be good at taking direction? Will she manage to keep a pleasing individuality but still bow to the senior women of the harem? In the three decades that Grandmother Zekiyé has been running grandfather’s household, no wives, concubines, or maidservants have entered the harem without her approval. But her choices have always been right, and Grandfather has always been pleased with them. Many of Grandfather’s peers have found life at home a strain, their peace soured by ill-tempered wives and warring concubines. There is a growing trend in Constantinople and the larger towns of the Ottoman Empire for even the wealthiest men to turn their backs on the Islamic dispensation that allows them four wives and as many concubines as they can afford to keep, and instead to limit themselves to one wife and perhaps one or two women outside the house, women they keep in private villas and visit secretly. Zekiyé prefers the old ways that allow her to keep an eye on things. A well-run house can make its master’s life pleasant, and Grandfather has found himself able to avoid the drabness of marital monotony through the occasional introduction of fresh faces into his home.

The drawing-room door opens, and Grandfather enters. Zekiyé puts down the book she has been reading and hurries over to him. She, too, is dressed formally, in a floor-length evening gown. She holds her ostrich fan to her cheek, whispers something to Grandfather in French, and then points at the three girls, who are standing by the large window that opens out onto one of the harem gardens. Grandfather smiles and whispers something in reply, at which she pouts playfully and taps him on the shoulder with her fan. She hangs her arm in his, and they walk across the drawing room toward the frightened girls.

The girls, though unveiled, are dressed in long silk jackets that reach to the floor. Their first appearance before Grandfather is to be in the guise of modest Turkish maidens, the kind with which an Ottoman gentleman might wish to fill his household.

“They are an attractive assortment,” Grandmother Zekiyé says in French.

“That they are,” Grandfather replies.

“I am particularly pleased with the green-eyed one,” Zekiyé continues, pointing her fan at my grandmother Maria. “Shall we view her first?”

They walk up to Maria, who looks directly into Grandfather’s eyes and then slowly lowers her gaze, as Zekiyé told her to do when she prepared the girls for the viewing. Your future master will want to see your eyes, Zekiyé said, but only for an instant; a girl must not stare into a man’s eyes for too long, even if he is to be her master.

“She speaks a pretty Turkish,” Zekiyé says. “It’s strange, and un peu tartare, but it is pretty.”

“Greetings. I am Mehmet,” Grandfather says to Maria.

“Greetings. I am Maria,” Maria answers, looking up again, though she is not sure whether she is supposed to. His monocle catches her eye, and she is amazed that the round piece of glass can remain in place. He is older than she expected. There is silver in his hair. She had thought her future husband would perhaps be her brothers’ age, but now realizes how foolish that thought was: a great man, a grandee, would be one who has done many things in his life, not a boy. Still, Mr. Mehmet is too distinguished to be a bridegroom, she thinks, surmising that he must be her master’s father, the head of the household, who has come to view the girls who are to be the brides of his sons. This morning Zekiyé did not introduce herself to the girls—she just assembled them in a small chamber and with gestures and simple Turkish phrases told them what to do. So Maria believes Zekiyé might be her master’s mother. What if they don’t like me and send me away, she suddenly wonders in fear.

“Greetings, Maria,” Grandfather says, pronouncing her name in a strange and foreign way.

“Greetings. I am Maria,” she says, and then smiles, realizing she has just repeated herself. Grandfather smiles too.

“She has a pleasant voice,” he says to Zekiyé. “She does not mind looking me in the eye. Très vivace.”

With her fan, Zekiyé motions Maria to lower her eyes. Maria lowers them. There is gold everywhere in the room. Large vases stand in all the corners and on the tables; they are old, perhaps even ancient, but they look so clean and polished they might be new. Maria wants to raise her head and look around but knows that she must not. She rests her eyes on the lowest shelf of books lining the wall before her. She has never seen so many books. In her Greek village back in the Caucasus, the priest had a Bible and two thin volumes of Byzantine chants, and Black Melpo the Medicine Mixer had the piles of yellowed penny novels written in Pontic Greek. But Maria has never seen beautifully bound volumes like these, their spines covered with strange gold letters.

“She is thin, but in a good way,” Zekiyé says in Turkish. “Her thinness has not affected her breasts. And her hips will widen when the time is right.” She taps Maria’s hip. “She might well bear you some boys.”

Maria looks up. She has understood Zekiyé’s words about bearing boys, and realizes that Mr. Mehmet is not her master’s father, but her master. She is so startled by this that she cannot tell if she is pleased or dismayed. Zekiyé does not notice that Maria has raised her eyes again. Grandfather steps back a few paces to view her from a distance. He smiles. She breathes in carefully so he will not think she is flustered. She looks at his face, then lowers her eyes again. So this is the face of the man who is to be her husband. He is clearly a good man, a kind man, she thinks, even if his eyes are difficult to read. He has smiled at her, which probably means that he is pleased; he has saved her family and all the others by sending them so many gold coins before even having met her. She doesn’t dare raise her head again but thinks she can feel his cool eyes on her. His eyes are a bright hazel and were the first thing she noticed about him when he entered the room. They are unusual eyes, she thinks.

Outside, in the harem garden, two little girls in frilly white dresses are chasing a boy of about 10 who is wearing a sailor suit and hat. Maria watches them out of the corner of her eye. The boy shouts shrilly as the taller of the two girls catches him and pushes him to the ground. Zekiyé opens the French doors that lead onto a terrace and waves her fan at the children. “You naughty things!” she calls out. “You are disturbing your Papa! Papa cannot hear himself think!”

The children run down the path past a pond and disappear among the trees beyond it.

Zekiyé closes the French doors and smiles apologetically at Grandfather, even though the children are not hers, but his third wife’s. She goes over to a large oil painting of a young shepherdess in a white and pink dress, stares up at it, and then glances at Grandfather, who is looking at Maria with thoughtful eyes. Maria looks at the painting, knowing she is expected to avoid his gaze. She notices that the shepherdess is holding a stringed instrument, its precious lacquered wood gleaming; there is a diadem of blossoms in her hair—a princess perhaps, dressed up as a shepherdess, Maria thinks, but then sees that the subject of the painting is undoubtedly Madame Zekiyé as she must have looked many years ago. Madame Zekiyé quickly walks toward Maria. “Pretty eyes, pretty complexion, good breasts, mon cher,” she says to Grandfather, reaching out and touching Maria’s chest with her forefinger. Maria steps back in alarm, holding her hand over her breasts. Zekiyé smiles and wags a finger at her, and Maria smiles back at her nervously.

Four Months Earlier, Spring 1909, in a Greek Settlement in the Caucasus

As they flee, the tea plantation below the village is burning. The great lady of the house, a Russian noblewoman, has been slaughtered along with her daughters and servants and all the guards. The village elder, who tried to hide in her stables, is murdered as well. The priest runs barefoot and sobbing through the muddy field, his cassock hitched above his knees, thorns and stones cutting his feet, but the men catch him at the line of trees at the end of the field, the tall ash trees blocking his escape. Their machetes hack at his hands and feet, and he tumbles into the mud, his blood pouring onto his murderers as he tries to crawl away. Platoons of marauders are dragging the wounded and dying out onto the burning field where the dead priest lies, tearing off their victims’ smocks and trousers and defiling them in unspeakable ways, guffawing and firing their rifles. They torch the grand house and its granaries and barns, throwing into the flames boxes of flaring cartridges, walls of fire stretching down into the valley beyond the plantation. The massacring horde comes swarming up toward the village, and with the church bells ringing, the villagers flee, dragging the old and the sick with them toward the forests. Maria’s father opens the sheds and the sheep pen under the house to let the animals escape; he slits grain sacks and tears open cupboards, cursing and shouting profanities. His fields and goods, Maria’s dowry, everything is lost, and his wife Heraclea runs at him, shrieking, beating his back with her fists, “We must go, we must go! They will cut our throats!” As she throws woolen smocks, shirts, and pantaloons into a bundle, he tries to set fire to the house so the marauders will find nothing, and Heraclea pulls him away, ripping his shirt in her frenzy. She grabs Maria by the hand and drags her out of the house, ready to abandon her husband to his fate, but he follows them, crying like a boy, holding his rifle and the bundle of clothes that Heraclea has thrown into an empty flour sack. “I will shoot anyone who comes here, I will shoot them all,” he weeps. There is a shelf above the door with a row of large round loaves of bread, and Maria, too short to reach it, throws her bundle at it, the loaves toppling onto the floor. “Run! Run!” her mother screams, her flailing hand hitting Maria across the cheek, but Maria snatches up two loaves, one falling and rolling into the ditch as she runs out of the house.

A swarm of refugees is descending from the raided Greek mountain villages of the Caucasus, trudging through the forests and over narrow mountain paths toward the borderlands of the Ottoman Empire. Fifteen-year-old Maria is among a group of villagers who have gathered from various burned-down settlements. More and more people join Maria and her parents as they make their way toward the border river. Some have been marching for two weeks, some for three, sleeping in the open, their campfires keeping forest dogs and wolves away. They are all hard people, having lived like their ancestors through generations of disaster, upheaval, and plague. The land once belonged to Colchis, to which Medea had brought shame and destruction; it has not been Greek for a thousand years, and although they continue to live there, their numbers are dwindling as the raids grow fiercer, the plagues more frequent.

The refugees cross over the fast-flowing river and into Ottoman territory in leaky boats and climb up a winding mud trail in the rain, toward a place where, they have been told, there are some abandoned barracks. Maria’s father, Kostis, is leading the way, climbing over brambles and fallen branches. His rifle is slung over his shoulder, and on his back he is carrying the large flour sack filled with clothes and blankets, now wet and heavy in the rain. He beats at weeds and bushes with a stick to clear the way for the others. Camels graze among the trees by the side of the path, gaunt and skeletal animals that have barely survived the winter and are not worth shooting for a few strips of meat. A scent of eucalyptus and putrefaction hangs in the air. Since railway lines now cross Anatolia, the great caravans have been disbanded and the camels released to die in the wilderness. Kostis sees a deer and tries to take a shot at it, but the primer in his rifle is wet from the rain. They could have strung up the deer on a tree, out of the reach of the jackals and wolves, he says, and then come back for it once they had found the barracks. “No point wasting bullets now,” Heraclea tells him in a low voice, so that the others won’t hear her talking down to her husband.

Kostis turns and looks back at Maria, then looks away again. Her mother is walking some distance behind him, her feet slipping in the mud, a bundle in her arms as large as his but heavier, for as they fled, she scooped up a tin bowl that had been part of her dowry many years before, as well as three boxes of cartridges. Kostis in his confusion and rage was about to take the rifle with a single cartridge in it; had Heraclea’s mind not been as nimble as it was, he’d now be carrying a whole rifle for nothing, with just a single shot. The barracks to which they are heading, she knows, are in the middle of nowhere; the nearest settlement, the people at the river said, lies a day’s ride north. Heraclea has 10 rubles hidden in the hem of her skirt, but none of that must go for cartridges. She stares at the path in front of her feet, her lips moving as she counts every stone larger than her shoe; if someone were to give her a kopeck coin for every 10 stones, she might have a whole ruble by the time they reach the barracks, maybe more, and she imagines all the things she could buy. Maria knows it is best not to disturb her mother during these counting games in which she gathers imaginary coins for things she sees, people who cross her path, or the number of birdcalls she hears. Heraclea would get angry if she lost count. Maria walks sullenly behind her mother in the rain, careful where she steps because she is wearing the shoes she has previously worn only on Sundays and at church feasts, the pair in which she was to have been married and buried. Village girls like her spend their lives barefoot in summer and wearing straw sandals wrapped in fur in winter, but Maria had the foresight to snatch up these shoes as they fled their burning village. She wears them now, knowing that even a small cut on a sharp stone can fester into a gangrenous wound in these dangerous valleys.

“I see trouble ahead, lots of trouble,” Heraclea mutters.

Maria looks at her.

“What are we going to eat?” Heraclea says, wiping her wet sleeve across her face, her voice low enough that only Maria can hear. “Those dried-up camels that look more dead than alive? Nothing but mud and brambles since we crossed the river. We’ll starve before the week’s out.”

Maria looks at the junipers and oaks and alders just beyond the mud trail, the trees gathering into a dense forest deeper in the valley. There is much more than mud and brambles here, she thinks.

“We’ll starve before the week’s out,” Heraclea says again. “I’m hungry already.”

Maria says nothing. She knows her mother is not interested in a reply or an opinion. Her mother can’t be hungry: her father bought lamb shanks from a tribesman by the river yesterday; they ate some of the meat last night, half raw and bloody, and the rest this morning. The tribesman had demanded 15 kopecks. “If you want it, you buy it. If you don’t want it, you don’t buy it,” he had said. Kostis had managed to buy the meat for nine kopecks, pressing the battered coins into the man’s hand, but Heraclea saw the expensive transaction as a symbol of calamities to come. “It’s a harsh land,” Heraclea says. “Who’d think crossing a river you’d be in another world, just like that? You’d think both sides of a river would be the same. I wouldn’t have come here for 50 rubles if I’d had a choice, nor 60 neither.”

Kostis glances back, thinking Heraclea is speaking to him, but looks ahead again.