In 1939, when the British playwright Tom Stoppard (born Tomáš Sträussler) was a year and a half old, he and his family fled Moravia ahead of the Nazis. In January 1942, they fled again, this time from Singapore to escape Japanese troops. Unfortunately, as Hermione Lee narrates in her biography, Tom’s father, Eugen Sträussler, a doctor, could not leave with them. The ship he finally scrambled aboard two weeks later was bombed and sunk, killing everyone on board. Tom was not yet five years old.

Their own trip rerouted, Tom, his brother, and his mother ended up in India instead of Australia, as they’d intended. Toward the end of their four years there, Marta Sträussler married a British soldier named Kenneth Stoppard, and the family moved to England. Tom never felt close to his stepfather, but he did fall deeply in love with his adopted country, its language, and its ways. English freedom exhilarated him; he experienced himself as uncensored, able to create whatever he wanted—the opposite of what he would have faced had he returned to Eastern Europe. Although he attributed these virtues to a place, I suspect they might also have expressed the positive side of his fatherlessness: his feeling unconstrained by paternal authority, and not pinned down by tradition or demands for fidelity and obedience.

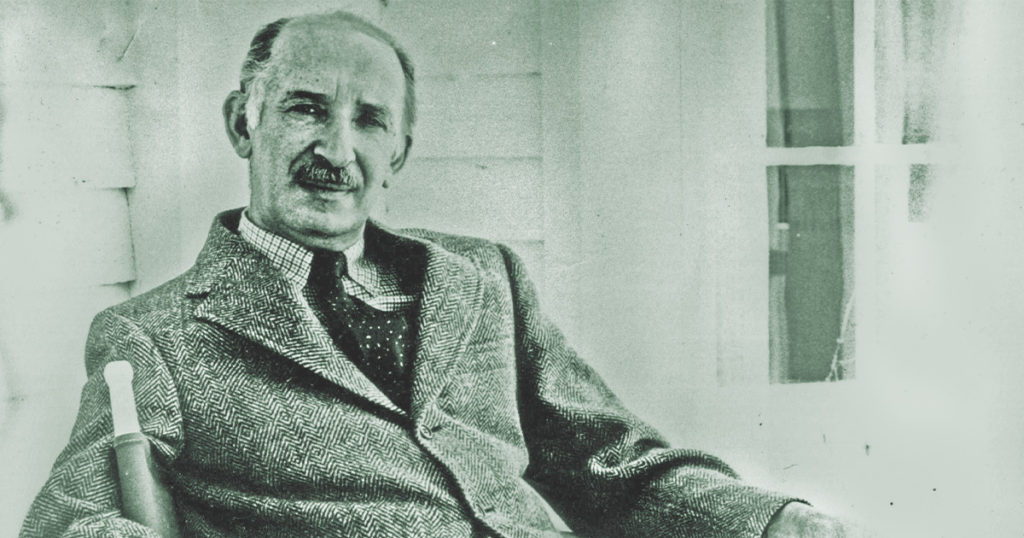

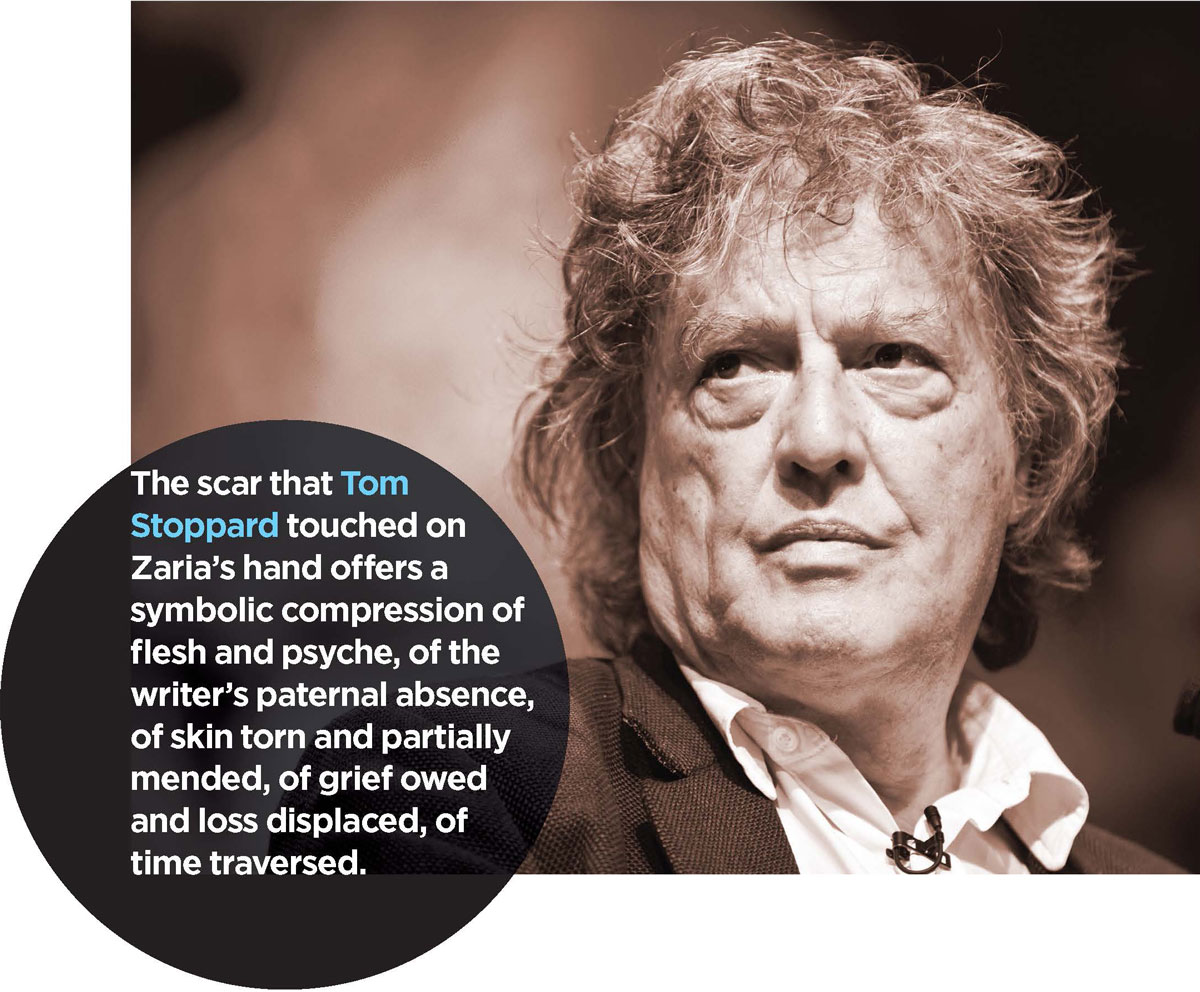

Almost a lifetime later, in 1998 and ’99, the playwright visited his old home in Moravia—now the Czech Republic—finally curious about his family past. While there, he spoke with a woman whose hand his father had stitched when she was a little girl. Stoppard wrote, “Zaria holds out her hand, which still shows the mark. I touch it. In that moment I am surprised by grief, a small catching-up of all the grief I owe. I have nothing that came from my father, nothing he owned or touched, but here is his trace, a small scar.”

Stoppard’s account resonated with a sentence I’ve long loved from a talk he gave in 1999. Describing the theater revolution embodied by Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter, he said about their work, “These plays, so unlike Shakespeare, did the thing that makes Shakespeare breathtaking and defines poetry—the simultaneous compression of language and expansion of meaning.”

The phrase captures one way literary craft guides the unconscious mind, allowing tight-wound—as in a spring, or perhaps tight-wound as in a scar—energy to fuel the creation of art. The scar that Stoppard, by then in his early 60s, touched on Zaria’s hand offers a symbolic compression of flesh and psyche, of the writer’s paternal absence, of skin torn and partially mended, of grief owed and loss displaced, of time traversed. It is also one source of creative energy, and a point of origin from which a discussion of writers and early parental loss might expand.

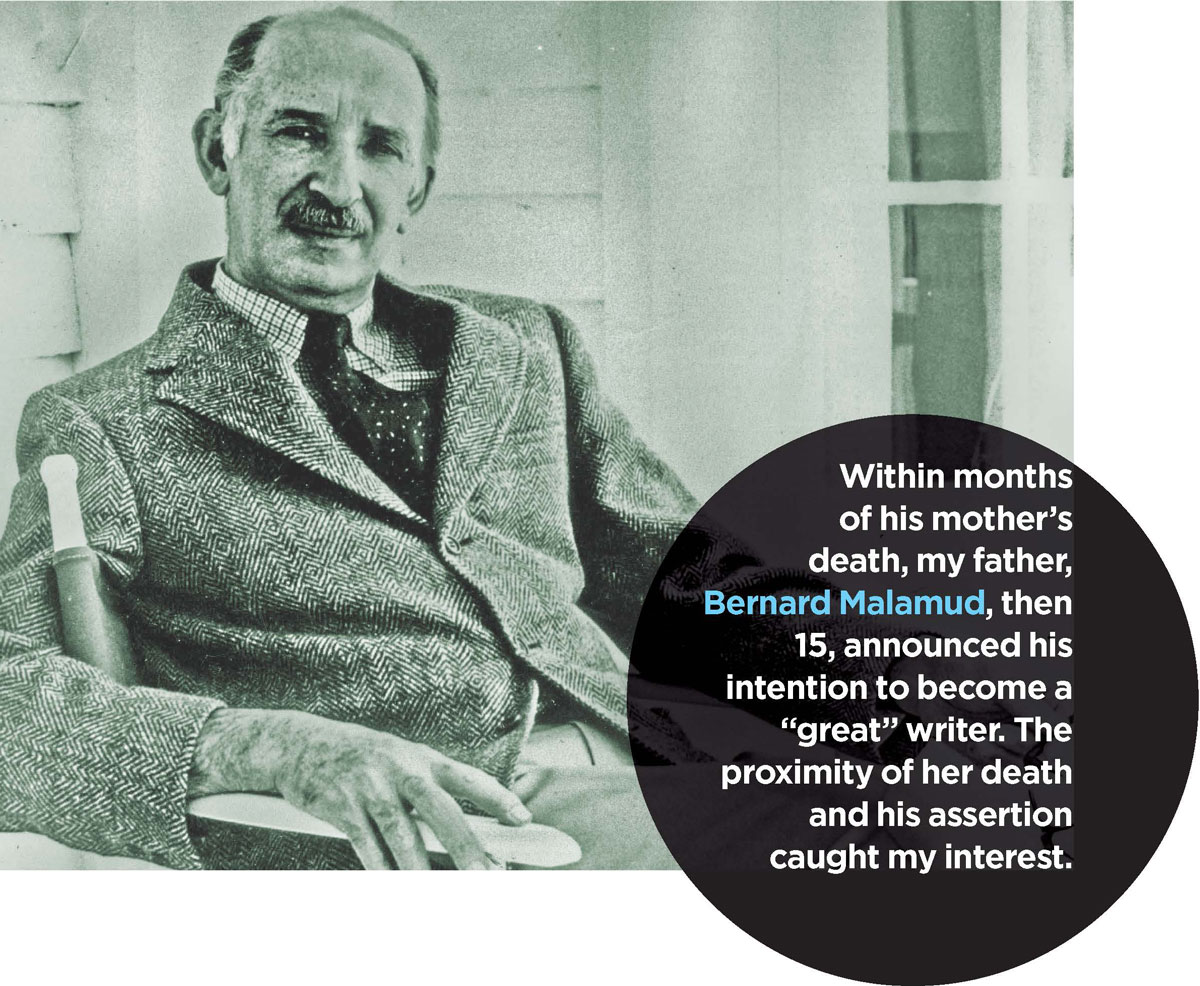

I first got interested in this question long ago, when I began contemplating the story of my grandmother’s death—which occurred in 1929, when my father, the writer Bernard Malamud, was barely 15. Bertha Fidelman had schizophrenia and died in an asylum at 43. Perhaps from pneumonia, perhaps from suicide, likely from a broken heart after being separated indefinitely from her husband and children, thanks to her untreatable illness and their poverty. Within months of her life’s ending, her older son had announced his intention to become a “great” writer. The proximity of her death and his assertion caught my interest.

Years later, writing a memoir, I corresponded with some of my father’s childhood friends. Several told me how, when “Bernie” spoke of his lofty ambition, they experienced him as some mix of irritating and pretentious. He was a poor immigrant kid who spoke no English until grade school, from a floundering family, someone whose only books at home were a set of the Book of Knowledge encyclopedias that his grocer father had scraped to buy Bernard when he was very ill with pneumonia. Lucky for him, he’d had teachers in grade school and high school who introduced him to poetry, stories, plays, and novels. Reading through his journals, I calculated that it took him more than 20 years of daily practice and intermittent despair before he wrote well enough to publish in 1952 his first novel, The Natural. Raw hunger, yes, and luck, but also stringent self-discipline and relentless practice helped him make his way. He was determined, driven really. A man running hard, sliding under fate’s menacing reach, trying to elude the tag.

I soon found myself noticing how often writers had lost a parent early. Yes, my sleuthing has been partial; most writers have not had a parent die; and across centuries, whether from disease, enslavement, oppression, poverty, war, or genocide, parents often died before their children grew up. But the list is still remarkable. And although death is the most absolute rupture, the physical and psychological variations of abandonment and loss are numerous, and similarly seem to lead some people to write.

Let me begin with an incomplete list of writers who came of age after their parents died. I have divided it into three groups—mothers, fathers, and both parents—but otherwise I have left it so it can tumble out: a gathered flock, released. Someone who read it called it a Kaddish. Okay.

Mothers

Emily Brontë was three when her mother died; her older sister Charlotte was five. Zora Neale Hurston was 13, as was Virginia Woolf. Amos Oz’s mother committed suicide when he was 12. Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s mother died nine days after he was born; Marguerite Yourcenar’s 10 days after she was born; and Mary Shelley was 11 days old when her mother died. Rabindranath Tagore, the youngest of 14 children, was 13. Stendhal’s mother died when he was seven, Molière’s when he was 10. Penelope Fitzgerald was 18. William Maxwell’s mother died during the 1918 flu epidemic when he was 10. Saul Bellow’s when he was 17. George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans) was 16 when her mother died, though Evans had boarded out for schooling starting when she was five. Stevie Smith’s father abandoned the family when she was tiny, and at five she was sent to a tuberculosis sanitarium for three years; her mother died when she was 17. Edward Gibbon’s mother died when he was nine, and all six of his siblings died in infancy. Voltaire was seven, Daniel Defoe most likely around the same age. Harriet Beecher Stowe, five. Henry Fielding, 10. Elizabeth Bowen, 13. John Bunyan, 15. William Cowper, six. A. E. Housman, 12. Stéphane Mallarmé, five. Pablo Neruda, two months. Katherine Anne Porter was two years old. Clarice Lispector was eight.

Fathers

Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre both lost their fathers as toddlers. Susan Sontag was five when her father died. Mary Gordon was seven, as was Octavia Butler. So too Elias Canetti. John Donne was four. Baudelaire’s father died when he was six. Lorraine Hansberry’s when she was 15. Mavis Gallant’s died when she was 10, and her mother then moved away. Lord Byron was three. Jan Morris was 12. Ralph Ellison, three. Theodore Roethke, 15. Fernando Pessoa, five. Sylvia Plath, eight. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, eight. Jonathan Swift’s father died before he was born. Émile Zola’s father died when he was six years old; so too James Agee’s, in a car accident. Ford Madox Ford, 15. Matthew Arnold, 19. Saint Augustine, 17. Ralph Waldo Emerson, seven. Bret Harte, nine. Nathaniel Hawthorne was four. George Herbert, three. Herman Melville was 12. Tobias Smollett, two. William Thackeray, four. Mark Twain, 11. Constantine Cavafy, seven. Stephen Crane, eight. E. M. Forster was one. Joseph Heller, five. Cesare Pavese, six. William Saroyan, three. Hans Christian Andersen, 11. John Berryman, 11. Delmore Schwartz, 17. Isak Dinesen, 10. Robert Frost was 11, as was André Gide. Thomas Mann was 15, as was Flannery O’Connor. Amy Tan’s father and brother both died of brain tumors when she was 15. Sean O’Casey’s father died when he was six. Malcolm X’s father died or was murdered when he was six; his mother was institutionalized when he was 14. Sybille Bedford was 14 or 15 when her father died of appendicitis.

Both Parents

Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s mother died when he was 15, his father two years later. Leo Tolstoy’s mother died when he was not quite two, his father when he was nine. Maxim Gorky was an orphan by 11. Both of Mary McCarthy’s parents died in the 1918 flu epidemic, when she was six. Frederick Douglass’s father was unknown to him, and he was separated from his mother at birth, visiting with her only a few times before she died when he was seven; he was taken away from the grandparents raising him at six. Joseph Conrad was eight when his mother died, 11 when he lost his father. Jean Toomer’s father died when he was nine, his mother when he was 12. J. R. R. Tolkien’s father died when he was four, his mother when he was 12. Edgar Allan Poe was parentless before he was three. William Wordsworth’s mother died when he was seven, his father when he was 13. John Keats was eight when his father died, 13 when he lost his mother. Jean Racine lost his mother at one and his father at three. When Conrad Aiken was 11, his father murdered his mother and committed suicide. Dante lost his mother at six and his father at 17. W. Somerset Maugham lost his mother at eight and his father at 10. Gertrude Stein’s mother died when she was 14, her father when she was 17. In a grim parallel, Elie Wiesel’s mother was murdered by the Nazis when he was 15, his father when he was 16.

As I started researching, it turned out I was not alone in my interest. In Parental Loss and Achievement, published in 1989, four researchers in the United States and Switzerland explored the phenomenon and made their own lists of successful “orphans”—writers, artists, philosophers, and political leaders—who had lost one or both parents early. They created metrics of accomplishment, examined encyclopedia entries, and gathered statistics. They concluded that parental loss before 21 was disproportionately represented among those with high levels of achievement. I can’t assess the methodology, but they believed that their findings were significant. (Someone has since counted 10 U.S. presidents—or nearly one fourth of the total—who had lost their fathers by or before age 16.)

The book’s authors did not explore them, but of course there are many ways for children to “lose” parents. Consider Pat Barker, born “fatherless,” and raised by her embarrassed young mother as a sister instead of a daughter. When Barker was seven, her mother married and left, and Barker chose to stay with her grandparents. Isabel Allende’s father left the family when she was three. Shortly after Gabriel García Márquez was born, his parents moved away, leaving him with his maternal grandparents until he was nine. Richard Wright’s father left the family when he was five years old, and they did not see each other for 25 years.

Or consider the 19th-century Italian novelist Alessandro Manzoni, who was immediately handed over to a wet nurse and then sent to religious boarding schools. He got to know his mother only in his 20s. Or John le Carré (David Cornwell), whose mother left him when he was five and didn’t contact him for 16 years. Or Lawrence Ferlinghetti, whose obituary in The Guardian recounts, “His father died before he was born and his mother was committed to a mental hospital, leaving him to be raised by his aunt. When he was seven, his aunt, then working as a governess for a wealthy family in Bronxville, abruptly ran off, leaving Ferlinghetti in the care of her employers.”

Some writers lived with parents who raised them but experienced them as deeply unavailable, or traumatizing. Shirley Hazzard was born in Sydney, Australia, to a mother ill with a bipolar disorder and an alcoholic father, before either condition was deemed treatable. She seemed to barely survive her childhood. James Baldwin’s mother left his father while she was pregnant with him and later married a man with whom she had eight children in rapid succession; her husband scapegoated and abused James. F. Scott Fitzgerald observed about his own life, “Well, three months before I was born my mother lost her other two children. … I think I started then to be a writer.”

Or the graphic novelist Alison Bechdel, who felt she had mothered her mother as a way to maintain a functioning parent. (Her father died when she was 19.) Throughout her graphic memoir Are You My Mother? she seeks both to understand her mother and to draw out roots of her own artistry within the psychological tangle of their relationship and their traumatic family life. Her early psychological loss of her mother seemingly marks a scar upon her soul.

What are we to make of this long list? Is it mostly a nod to human suffering, one more acknowledgment that pain often walks arm in arm with writing? I think it’s more than that.

I am not suggesting that writers’ creativity, the slapping freshness and originality of their best works, can be reduced to early trauma at the loss of father or mother—or anything else, even if some soils offer fertile seedbeds. Knowledge of the ways of the unconscious together with contemporary skepticism of gendered certainties suggest we not generalize too broadly about the meaning of maternal versus paternal loss. Much of what might help us understand why and how someone comes to write can only be learned from them, including through the exploration of their unconscious life. A person onto whom we project sorrow may mostly be feeling liberated or relieved.

It is also helpful to underscore the primacy of chance in the way any life unfolds. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, the play that made Stoppard famous before he was 30, opens with the two men on stage. Guildenstern repeatedly tosses a coin and repeatedly wins the toss—“Heads, heads, heads.” His run is impossible, and yet there it is. His purse fills with coins while Rosencrantz’s empties. As others have noted, the scene succinctly encapsulates the playwright’s keen awareness of how, no matter what we might wish or believe, chance ultimately rules us all. Like gulls somersaulted by gales, our lives are tossed by huge distant forces, tiny local circumstances, and unlikely landings. One ship carries you to safety though not on the continent you intended. The other sinks, killing your father, leaving you without explicit memories or mementos. Meanwhile, in your unconscious, the parental absence ferments into ambition to “become someone.” Yes, you’re smart, hungry, energetic, talented, disciplined, capable. But will chance offer you a chance?

It’s not surprising that ambition to achieve is one response to early loss. Might not such a wish naturally follow from glimpsing close up the finality of death? Or feeling the pain, diminishment, deprivation, chaos, and absence that trail after? The wish to grow very big, shine very bright, inhale pride; to insist “I exist,” “I am here,” “NOW”; the urgency to be remembered, to feel immortal and perhaps able to recursively bestow that immortality onto the dead parent through your accomplishments. Ambition labors like an injury lawyer for the soul, seeking compensation for immense violation. Nor is it hard to imagine dreams of achievement among the analgesic fantasies that trickle, drift, or flood into the heart’s empty spaces.

With uncanny relevance, Freud, in his essay “Creative Writers and Day-Dreaming,” uses the example of “a poor orphan boy” to illustrate the power of fantasy to sustain a child. In the essay, the fictional orphan is given the address of an “employer where he may perhaps find a job.” Freud describes the boy conjuring up daydreams—from being hired and gradually promoted, to marrying the boss’s daughter—as he heads toward the interview. Freud notes the restorative function of such stories, how they allow the orphan to regain what he “possessed in his happy childhood—the protecting house, the loving parents and the first objects of his affectionate feelings.”

I suggest we imagine such playful, serious, even agonized, dreaming as the molten glass from which “orphaned” writers—in this metaphor artists working in glass, blowpipes against lips—puff and craft glob after glob into distinctive creations. The process of shaping the glass can represent the child’s great wish to exercise some small bit of control over a mystifying cosmos.

The phrase poor orphan also suggests a pragmatic reason why writing might become the form chosen by someone in search of a sustaining craft and vehicle of achievement; that, until very recently with the flowering of MFA programs, there have been few institutional gatekeepers. Writing has been an art form you could teach yourself by reading and practicing, perhaps seeking out a mentor—although I do not mean to imply that everyone has equal access. As the Canadian writer Alistair MacLeod (whose father was a coal miner, and whose parents apparently did not die young) said to me once when I met him: To write, you “have to have a chair to sit in and time to sit”—something his early life did not readily provide.

Once there is a chair, the writer, in Freud’s words, can invest fantasy “with large amounts of emotion.” Emotion that buzzes like bees who have lost their hive. Mary Gordon illuminates the usefulness of such an investment to the bereft child. Gordon’s father was the parent who made her feel intensely loved and very special. In her memoir The Shadow Man: A Daughter’s Search for Her Father, Gordon writes how, after he died, she began telling herself stories, transforming the ordinary “into the sacred.” “I wrote my father’s history as one of the Lives of the Saints.”

“By doing this,” she continues, “I could see my father’s death not as something that could have happened to anybody, an expected consequence of living, and therefore without meaning. Loss, absence, the half-life of my life, weren’t ordinary or purposeless. My father’s life and death became part of something grand, enormous. And so mine did, too. … When he died, I was a child of seven. I didn’t know what I was doing. What I was doing was telling myself stories. They were richer, more colorful, and more enjoyable than the texture of my daily life, which was marked by wrongness and loss.”

Gordon’s paragraph beautifully highlights what might be hypothesized as the increased draw of “transitional” space for children left alone after devastating losses. To say it another way, in the absence of a loved parent, the English pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott’s space of me/not-me, of reality/illusion, becomes more compelling, and as Gordon illustrates, more urgently necessary for comfort and psychic survival. The feelings that once went to a parent might there be offered a new hive or hideout, even an inviting quasi-erotic playground. In this space, you are Prospero. You hold the staff; you summon the storms that split ships.

Wordsworth wrote a sonnet about sonnet writing that speaks to the sanctuary offered within this transitional space. It begins:

Nuns fret not at their convent’s narrow room;

And hermits are contented with their cells;

And students with their pensive citadels;

Maids at the wheel, the weaver at his loom,

Sit blithe and happy …

A little later, he continues, “In truth the prison, into which we doom / Ourselves, no prison is …”

When children read, write, draw, daydream, and fantasize, they are practicing the nascent writer’s skills—telling stories, remembering, characterizing, closely observing those around them, while attending to their own internal worlds. The assertion of an “I” as narrator, of someone listening, together with the narrated fantasies, offer the weary psyche a spar on which to float.

In her extraordinary narrative, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Harriet Jacobs writes starkly about her experience of the before and after of parental loss, and one can conjecture something about the enduring sustenance for her of having felt loved and protected in her early years: “I was born a slave; but I never knew it till six years of happy childhood had passed away. … I was so fondly shielded that I never dreamed I was a piece of merchandise, trusted to [my parents] for safe keeping.” Jacobs’s mother died when she was six, her father when she was 13—although from six on, she lived in an owner’s house. As a teenager, Jacobs came to be owned through “inheritance” by a wealthy, married town doctor who tried to force sex with her. She resisted him ferociously, first by bearing children with another white man, finally by hiding in a tiny crawlspace in her grandmother’s attic for seven years before escaping north. She could hear her children and glimpse them through a peephole but not let them know she was alive nearby.

Many years later, when Jacobs published her memoir under the pseudonym Linda Brent, she acknowledged how a larger quest for justice allowed her to overcome her shame and write. “I have not written my experiences in order to attract attention to myself; on the contrary, it would have been more pleasant to me to have been silent about my own history. … But I do earnestly desire to arouse the women of the North to a realizing sense of the condition of two millions of women at the South, still in bondage, suffering what I suffered, and most of them far worse.”

How many stories must you have to tell yourself—and the world—to begin to make sense of such subjugation? For Jacobs, able to remember loving parents, a profound awareness of the aloneness, the torment, the erasing of happiness that followed on their loss appears as one psychic force driving her writing. So too, the urgency to seek witness, to offer her voice to assist others, to mitigate shame and seek restitution by becoming the one who tells the story, gradually impels her to put words to paper.

Although suffering drives some to silence, the internal pressure to narrate, the attempt to tame and contain chaos and pain, can also be an aftermath of loss. In “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” Coleridge begins, “It is an ancient Mariner, / And he stoppeth one of three.” The old sailor has to tell his bizarre tale to any stranger he can force to lend an ear. What if we imagine the mariner’s words tracing partly the nine-year-old fatherless Coleridge’s horror and loneliness, and, at the same time, the adult poet’s unconscious urgency to convey his experience, his own search for someone who will listen?

The mariner’s shipboard troubles turn deadly when he shoots an arrow that kills an albatross. That image is a reminder of many children’s fears of their own post-abandonment rage, together with the equally frightening unconscious, guilty question of whether they themselves might … perhaps … somehow … have been the parent’s murderer? Or at least are somehow culpable for badly messing up their own lives?

An ungraspable, existential mystery confronts a child after a parent has died or left. Here—gone; disappeared. The wounded psyche is left contemplating a crime that requires its own detective, someone as obsessed as Inspector Javert, willing to scour the scene, review the clues, and speculate. And then there is the tenuousness of subsequent relationships.

Coleridge’s poem shows how such nagging feelings are no small matter. Writing can be a search for certainty, for ink insistent on a page. The transition from done-to to doer creates power. Yet to invent original work, artists must route the affective turmoil toward their creative purposes. The process of writing, the search and placement of words, the mental turn and return sifting memory and fantasy, the discipline of craft, the satisfaction of the evolving story, the payment of guilt’s debt can all help to sublimate the arrow’s blood into art.

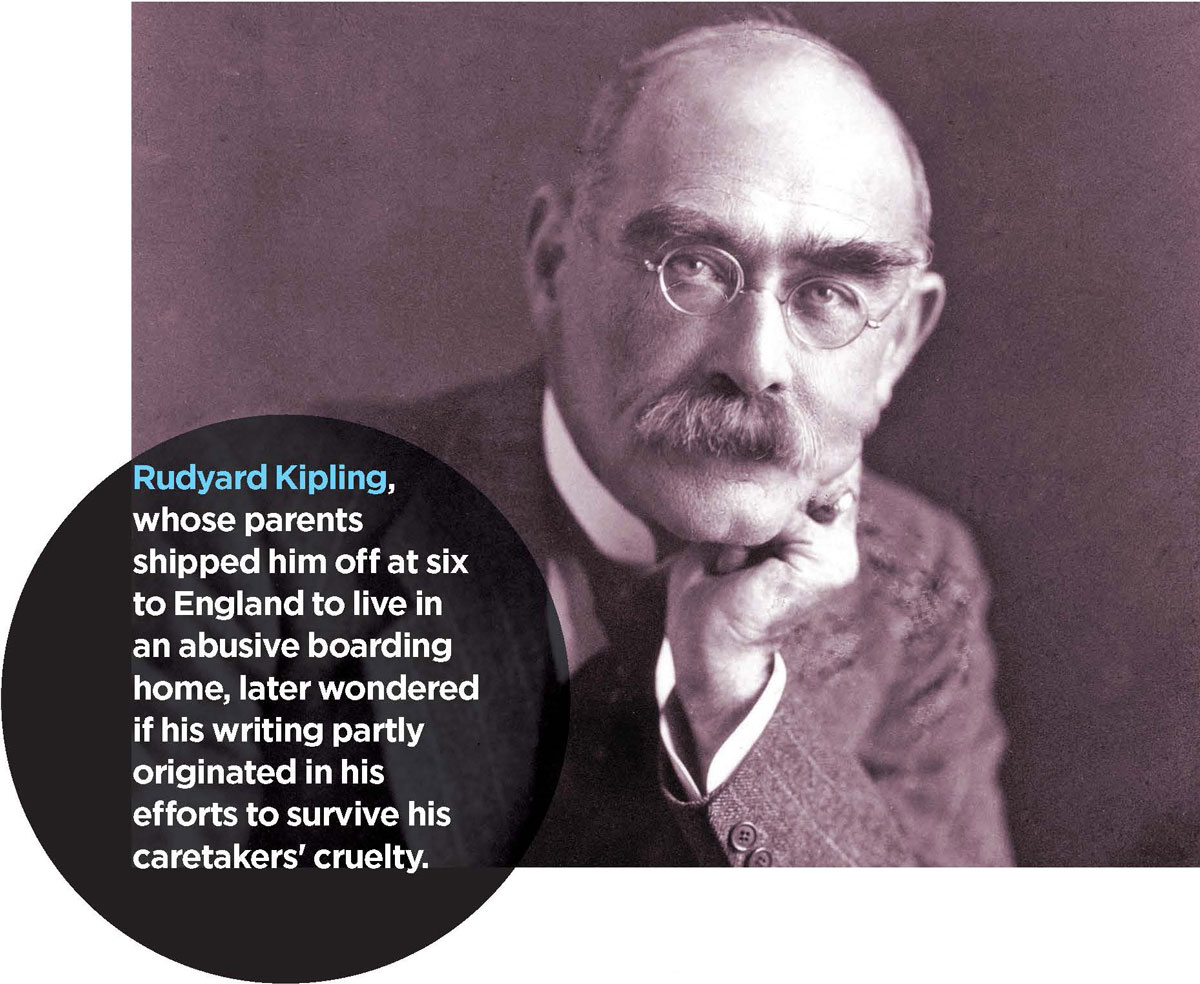

Rudyard Kipling, whose parents did not die prematurely, had to make sense of being intentionally cast away. Kipling’s mother and father shipped him and his sister from India to England to live in an abusive boarding home when Rudyard was six, his sister Alice, three. The parents appear not to have visited for half a dozen years and seemed indifferent to the children’s awful circumstances. Kipling later wrote, “I had never heard of Hell, so I was introduced to it in all its terrors.” A terror-filled hell. An incomprehensible change. The literary critic Edmund Wilson quotes Kipling’s sister, also a writer, who spells out the larger betrayal. “I think the real tragedy of our early days … sprang from our inability to understand why our parents had deserted us. We had had no preparation or explanation; it was like a double death, or rather, like an avalanche that had swept away everything happy and familiar.”

Kipling later wondered—a darker take on fantasy as a source of creativity—if his writing partly originated in his efforts to survive his caretakers’ cruelty. “[I]t made me give attention to the lies I soon found it necessary to tell: and this, I presume, is the foundation of literary effort.”

Intentionally lying, confabulating, fantasizing, and attempting to remember what is vague are cousins that share family features in spite of their different temperaments. And whereas Kipling emphasizes intention, young children’s distinctions among these states tend to be partial. Early parental loss might contribute to an ongoing difficulty differentiating lies from something else—as well as an ongoing compulsion to string together a story that will hold. Or, they might intuit that truth is an unaffordable luxury when survival is at stake. An older Polish writer I knew whose father and sister were murdered by the Nazis or their sympathizers used to castigate me for my naïveté: “So, Janna, if the Nazis knock on your door and want to know if you are hiding any Jews, you will tell them the truth?”

John le Carré, rather like Mary Gordon, presents storytelling as a way of burnishing an impoverished reality. Although le Carré believed that the phenomenon extended to all writers, we might initially locate it in his life—a mother who left when he was five, a sociopathic father who lied and lied. “We all reinvent our pasts … but writers are in a class of their own. Even when they know the truth, it’s never enough for them.”

A family crisis provoked by his father’s profligacy left Charles Dickens at 12 working in a factory and feeling a betrayal similar to what the Kiplings described. Making a comparison with his “happier childhood,” Dickens later wrote, “the sense I had of being utterly neglected and hopeless; of the shame I felt in my position; of the misery it was to my young heart to believe that, day by day, what I had learned, and thought, and delighted in … was passing away from me, never to be brought back any more, cannot be written.”

Let us pause to honor the elusive remnant that cannot be written, the suffering that remains as oppressive as it is ineffable, that refuses language and form, even after a prolific fiction writer fills thousands of pages with tales that grip legions of readers worldwide.

After Keats was orphaned at 13, he intuited that he would not live long enough to transcribe all that was in his mind, and indeed tuberculosis ended his life at 25. He famously laid out this awareness in a sonnet that begins,

When I have fears that I may cease to be

Before my pen has gleaned my teeming brain,

Before high-pilèd books, in charactery,

Hold like rich garners the full ripened grain …

Although Keats did not have time to stack reams of poems as he had wished, many writers do live to see their volumes on their shelves. It’s not hard to appreciate the desire: how books as objects might form a seawall against a surging tide, sturdy enough to keep an orphaned writer from washing away.

In a rich and complex essay about writing, “On Giving Birth to One’s Own Mother,” the novelist Jay Cantor discusses the abstract expressionist painter Arshile Gorky in a way that sheds light on an artist’s need for metabolizing trauma as a prelude to creating original work. Abandoned by his father, who fled the Armenian genocide and left his family behind, the 15-year-old Gorky held his mother in his arms as she died of starvation. Soon after, he and his sister emigrated to the United States. Cantor spotlights a 10-year period during which Gorky struggled to turn a photograph of himself with his mother into a finished portrait of them together—and failed because he could not get beyond painting her as “an icon, an adored Saint.” Cantor suggests a trajectory during which Gorky gradually broke free from depressive, frozen grief—and static representation—to painting with full energy, aliveness, and originality. He finally could “let his mother, in himself, be reborn as his creation.”

“To let his mother, in himself, be reborn as his creation”: what a gorgeous summary of artistic progression and long struggle.

In Creative States of Mind, the psychoanalyst and artist Patricia Townsend offers a complementary and striking insight into such feelings of aliveness by describing the link between the creative process and the artist’s sense of wholeness: she suggests that while working on a creative project, artists have an unconscious experience of being both themselves and the absent, mirroring other. Townsend discusses how some of the professional artists she interviewed reported feeling their most vivid sense of aliveness while they were in the process of creating an artwork. Referencing both Winnicott and the psychoanalyst Kenneth Wright, Townsend writes, “The artist acts on the developing work and that work responds by becoming more attuned to her experience, and it is this fluctuating relationship that makes the artist feel more alive.”

Large, unconscious shifts of feeling can also follow upon a work’s completion, in part because writing can be a form of grieving. Virginia Woolf felt a sense of release only after she finished To the Lighthouse. Woolf wrote, “When it was written, I ceased to be obsessed by my mother. I no longer hear her voice; I do not see her.

“I suppose that I did for myself what psycho-analysts do for their patients. I expressed some very long felt and deeply felt emotion. And in expressing it I explained it and then laid it to rest.”

As an adult grappling with her discovery of her father’s hidden past, his large lies and rabid hatreds, Mary Gordon struggled to make her peace: “Finally, it was only by turning my father into a fictional character after all, by understanding that I could never know him except as an invention of my own mind and heart, that I could make a place for him in my life.”

Isn’t that what we each do, writers or not, after much effort: make what peace we can by reinventing parents so that they can take their place in our lives, mold them to our purposes while we still live?

Perhaps Tom Stoppard’s jolt when he touched Zaria’s scar was not only grief and loss but also a whoosh of unbearable glee at having survived. Tomáš Sträussler did not die. He sailed safely on, surfaced, gulped air, began groping for words from which to spin tales and beget lives. Or as Calvin Cohn put it in my father’s novel God’s Grace, speaking, I believe, at this moment for my father: “Merciful God,” he said, “I am an old man. The Lord has let me live my life out.”

Like them, finally all orphaned, we cultivate our fictions, bury our dead before our own bells toll. Gripping hard the shovel, clumping the boot down, we slice deep into the soil, then, straining, gaping, toss high the earth-torn flash.

Photo credits: Tom Stoppard (Jeff Morgan 09/Alamy); Bernard Malamud (Interfoto/Alamy); Mary Gordon (Barbara Alper/Getty Images); Rudyard Kipling and Harriet Jacobs (Wikimedia Commons)