In these days of social distancing and self-imposed isolation, I am noticing things in their absence—for instance, the absence of sports as a constant background presence and diversion: scores popping up on smartphones, the faint hum of a TV broadcasting some forgettable midseason affair, social media clips of yesterday’s poster-worthy dunks and wonder goals. All is quiet, much in the way Center Court at Wimbledon can go quiet in an instant, although in this case without the anticipation of impending drama. It is a silent spring of a new order: all the sporting crown jewels in the coming months have been canceled (any that haven’t yet are sure to be, even if the organizers of the Tokyo Olympics are still holding out hope). Opening day in baseball has been pushed back, at least until mid-May. The French Open has been rescheduled for late September, an announcement apparently made without player input and one that has prompted talk of a potential boycott by Rafael Nadal, who with his 12 titles has ruled over Roland Garros like a fiery Spanish god. The Masters will be rescheduled for October, according to the latest rumors, long after the azaleas have shed their final blossoms.

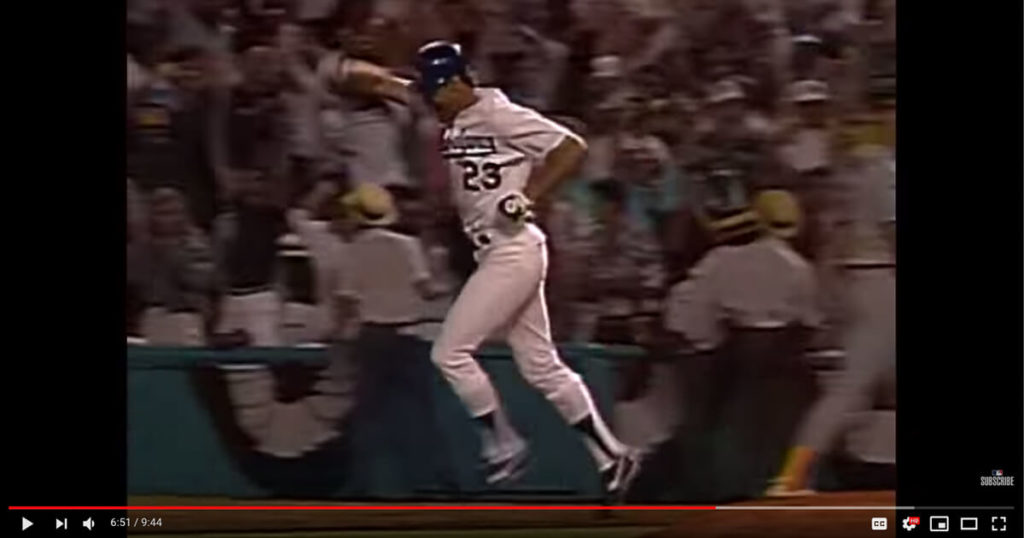

What’s a sports fan to do, except take a deep dive down the YouTube rabbit hole? Tiger Woods’s otherworldly chip on the 16th hole during the final round of the 2005 Masters; Diego Maradona’s “hand of God” finish against England in the 1986 World Cup; Nadia Comăneci’s remarkable succession of perfect 10s at the 1976 Olympics—they’re all just a few clicks away. Knock yourself out. Zip around long enough, and the algorithms may eventually offer up Kirk Gibson’s walk-off home run in Game 1 of the 1988 World Series, when Gibson, the Los Angeles Dodgers’ vaunted slugger, enfeebled by a balky left hamstring and bruised right knee, delivered a pinch-hit masterpiece that led to the Dodgers’ eventual triumph over the Oakland Athletics. It’s one of my favorite clips of sporting lore, in part because it offers up such a compelling mano a mano confrontation: the scrappy Gibson versus Dennis Eckersley, Oakland’s Hall of Fame closer. But mainly because, at about six minutes, the length of Gibson’s at bat, it hardly represents a big commitment while still managing to capture the ebb and flow of the game leading up to his heroics. Think of it as a sporting sugar rush, complete with the dulcet tones of Vin Scully, who gives a master class in broadcasting when he goes silent for more than a minute after Gibson hobbles around the bases, allowing viewers time to bask in the crowd noise, to revel in the moment, before he dispenses with this pitch-perfect summary: “In a year that has been so improbable, the impossible has happened.”

It’s a favorite clip of mine for another reason: it reminds me of my father. As a young boy in Leonia, New Jersey, my father was surrounded by Yankees fans, but because his middle name was Owen, and because the Brooklyn Dodgers’ catcher at the time—the early 1940s—happened to be Mickey Owen, he decided to swim against the prevailing tide. When the Dodgers decamped to Los Angeles after the 1957 season, my father maintained his rooting interest in the face of the betrayal, though the intensity of the flame, I imagine, must have been slightly diminished.

Fast forward to Game 1 of the ’88 Series. I was 12 at the time, and I had a paper route delivering the Trenton Times to my suburban development. In the mornings, my father would help me fold the papers, securing them with rubber bands, wrapping them in plastic bags when it was raining or snowing. As he always did, he sat on the stairs leading up from the hallway to the dining room of our split-level townhouse, holding court in his bathrobe, when he told me that he had gone to bed in the top of the ninth inning with the Dodgers trailing by a run, confident that with Eckersley taking the mound in the bottom of the inning, the game was surely over. As I got ready to embark on my route, I took a quick peek at the sports pages, where the news of Gibson’s heroics snapped me to attention. I remember holding up the headline for my dad in disbelief. I have no memory of his immediate reaction.

As I got older, the moment encapsulated what I believed to be an innate flaw in my father’s character—that he could never be spontaneous in the face of his daily routine, that when it was time to turn in, it was time to turn in, no matter what drama might be on deck. He wasn’t the only one who missed the fabled blow. In the YouTube clip, as the ball clears the stands, the brake lights come on from one solitary car that appears to be leaving the Dodger Stadium parking lot. I imagine a father telling his son that they should beat the rush, that the game is over, only to learn of his tragic error over the radio.

All these years later, now that my father is gone, I think less about his character flaws, especially now that my own have become so prominent, and instead think of how selfless he was to rise so early every morning to help me with the papers. For me at least, the YouTube rabbit hole offers up more than a sporting sugar rush. It helps me excavate memories, reminds me of the time my father and I spent a few moments together in the early morning darkness, and how, on that cold October morning, we marveled at how Gibson had managed to come through when all hope had seemed lost.

Watch Kirk Gibson hit his game-winning home run against Dennis Eckersley, in Game 1 of the 1988 World Series: