The Truth About Dallas

Looking back at the investigation of the Kennedy assassination and the controversies that dogged it from the start

More than half a century has passed since the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas and the months-long investigation by the Warren Commission. Those of us who served on the commission cannot forget those difficult, momentous times. Our conclusions seemed unassailable, yet ever since the commission’s report was released, we have constantly had to defend our findings. Critics and conspiracy theorists have questioned our competence and integrity, and even our commitment to finding the truth. On occasion, we have, either individually or together, responded to these challenges—in books, articles, and public lectures and debates. As the critical literature continues to grow, we would like to lay out one last time how we arrived at our conclusions, and why we are as confident as ever about what happened during those fateful days in Texas.

Because Jack Ruby murdered Lee Harvey Oswald two days after the November 22, 1963, assassination of President Kennedy, the prime suspect in the fourth presidential assassination in our history could not be publicly tried. That was not the case with those accused in the deaths of Presidents Lincoln, Garfield, and McKinley. The shocking nature of JFK’s murder, and the live national coverage that followed it, gave President Johnson little choice but to do something to address the intense public sorrow, anger, and curiosity that swirled through the nation and the world. He decided to appoint a prestigious, bipartisan presidential commission to determine the facts, in the hope that authorities in Texas and congressional committees would defer their own investigations. The president managed to persuade a reluctant Earl Warren, the Supreme Court’s chief justice, to lead the effort, and the famous commission bearing his name was born.

The members of the commission were Senators Richard B. Russell and John Sherman Cooper, Representatives Hale Boggs and Gerald R. Ford, former CIA director Allen W. Dulles, and diplomat and lawyer John J. McCloy. After reviewing preliminary reports from the FBI and other agencies in early December 1963, the commission decided that a substantial staff of lawyers had to be assembled as well. Ultimately, 22 lawyers were selected—including the two of us. J. Lee Rankin, a former U.S. solicitor general, was named the commission’s general counsel.

We staffers were anxious and determined and felt the weight of the task ahead of us. Regardless of age or background, all of us would later remember the enthusiasm and excitement of reporting for work at Washington’s VFW Memorial Building in early 1964. Many of us voiced our skepticism about the FBI’s view that Lee Harvey Oswald had acted alone and were determined to ferret out any conspiracy that the bureau had missed. At our first meeting with Chief Justice Warren on January 20, he told us of his reluctance to assume this nonjudicial responsibility, but went on to say that President Johnson expected the commission to find “the whole truth and nothing but the truth.” Warren, a former prosecutor, said emphatically, “That is what I intend to do.” He and Rankin would often remind us that “truth is our only client.”

The commission organized its investigation into six areas: the events on November 22, 1963; the evidence regarding the source of the shots; the identity of the assassin; the backgrounds of both Oswald and Ruby; the existence of any domestic or foreign conspiracy; and the policies and practices of the Secret Service, which was then under the auspices of the Treasury Department. Rankin insisted that the lawyers in each area analyze all the material provided by government agencies (principally the FBI, CIA, and Secret Service) or other sources before recommending witnesses who should appear before the commission or be questioned by its lawyers. We were uncertain early on about the commission’s readiness to conduct the extensive investigation that we thought was necessary. By the end of January, members of Congress and the media were increasingly critical about the apparent lack of progress.

The commission members wanted to hear first from Oswald’s wife, Marina, and scheduled her for February 3, 1964. She was obviously an important witness with unique knowledge about her husband’s defection to the Soviet Union in 1959, their life together in Minsk, and the circumstances under which they were allowed to travel to the United States in 1962. She had already lied to federal investigators on two important points—denying knowledge of her husband’s efforts to assassinate General Edwin Walker in Dallas in April 1963 and of his trip to Mexico seven weeks before the Kennedy assassination to get a visa to go to Cuba.

As Warren approached the VFW building on the morning of her appearance, the impatient reporters asked him, “Will her testimony be made public?” Yes, he responded, without hesitation, “but it might not be in your lifetime.” He went on to explain that national security concerns might require that some testimony not be immediately released, but the words “not in your lifetime” prompted public outrage and calls for Warren’s resignation. The commission’s response assuring full disclosure of the evidence it considered did not pacify these critics.

Occasional tensions developed between the commission and its lawyers. One of the first disputes erupted when Warren decided that Rankin would be the only staff lawyer allowed in the room during the questioning of Marina Oswald. Several of us were extremely troubled by the exclusion of Norman Redlich, a New York University law professor on staff who had spent the better part of January preparing for her appearance. Howard Willens’s journal from the time reads,

I held my peace until after the day’s testimony when Mr. Redlich and I went to discuss the matter with Mr. Rankin. It was our first heated exchange with Mr. Rankin. Mr. Redlich’s personal status was involved so I took the lead in asserting the proposition that Mr. Redlich should be in the hearing room and that the testimony should be elicited in the way in which we had planned it. I urged very strongly to Mr. Rankin that any other course of proceeding would ensure a mediocre record.

Upon further reflection, Rankin agreed that Redlich should participate the following morning. He recognized that the interrogation of witnesses would be more efficient and productive if the most knowledgeable lawyers were present to assist him and the members. This practice was followed in all future commission hearings.

In early March, the commission approved a schedule of witnesses to appear before it and authorized extensive depositions by its lawyers. The staff considered this decision to be important. From Willens’s journal:

In my view the adoption of this schedule is perhaps a more significant event in the internal operations of the Commission than is generally realized. It marks the commitment by the Commission to taking a considerable amount of testimony from witnesses with relevant information and to frame conclusions based on this testimony independent of the investigation conducted previously by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and other investigative agencies.

This tentative schedule was subject to repeated modifications to meet the commission’s desires. After hearing four witnesses in early March

… the Chief Justice was expressing his opinion that more witnesses with significant testimony should be called before the Commission as quickly as possible. This was partly because the court was currently in recess. … He expressed his view that the medical witnesses were among the more important witnesses to be heard. … He indicated that he wanted to get our lawyers on the road as quickly as possible to interview witnesses. (Willens journal)

Needless to say, the schedule was changed to accommodate the chief justice’s priorities.

By the end of its investigation, the commission had heard 94 witnesses and considered the depositions of an additional 395—law enforcement authorities, ballistics and other experts, doctors, and lay witnesses—and examined more than 3,000 exhibits. As would be expected, witnesses had conflicting recollections, and the commission had to do what lawyers are regularly required to do: assess the credibility of each witness and evaluate all of the evidence. For example, many people who had been in Dealey Plaza at the time of President Kennedy’s assassination testified that they heard between two and six shots, with most hearing three shots. More than 150 of them were interviewed by the FBI or other agencies; many also testified before the commission or its lawyers. Based on different evidence (the three cartridges found on the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository, the bullet fragments found in the car, the wounds to President Kennedy and Governor John Connally, and the damage to the presidential vehicle), we concluded that three shots were fired. It was impossible to interview everyone who claimed to have been in Dealey Plaza on November 22, 1963, and over the decades, witnesses came forth who contended that they had heard more than three shots—and that they had not been interviewed or asked to testify.

The commission’s conclusion that a single bullet wounded both President Kennedy and Governor Connally resulted from a similar, although more controversial, evaluation of the evidence. Early on in the investigation, we found—contrary to the reports from the FBI—that one of the three shots from the book depository had missed the presidential vehicle and its occupants. After repeated viewings of the now-famous home movie shot by Abraham Zapruder and analysis of the medical testimony, we concluded tentatively that the first of the two other shots, after exiting the president’s throat, hit Connally, who was sitting in a jump seat in the limousine slightly below and to the left of the president. After wounding the president, the bullet retained considerable velocity, and there was no evidence that it hit any portion of the vehicle’s interior. Experts in the analysis of bullet wounds testified that the governor’s wounds would have been more damaging had he been hit by a pristine bullet.

We recognized that this “single-bullet theory” was likely to be controversial and recommended that a reenactment of the assassination be undertaken in Dallas to test its validity—something both the FBI and the Secret Service opposed. The subject was discussed in detail at a meeting on April 28, 1964, attended by representatives of both agencies.

This meeting was the culmination of many months of work by members of the staff … regarding the films and medical testimony. From the very beginning Mr. Rankin had been less persuaded than these [staff lawyers] that it was necessary to decide these problems with greater precision. Just prior to the meeting, however, Mr. Redlich had finally put his views into memorandum form which I believed persuaded Mr. Rankin that some effort was necessary if the Commission wanted to make assertions in its report which coincide with the physical facts. (Willens journal)

After this meeting and much further debate, the commission authorized a reenactment in May. With the cooperation of both the FBI and the Secret Service, this project provided convincing evidence that the single-bullet theory was the only supportable explanation of the wounds suffered by Kennedy and Connally before the final, and fatal, bullet to the president’s head. Notwithstanding this evidence, Governor Connally never accepted this explanation of his wounds.

Despite the lack of any contrary evidence, the single-bullet theory became one of the most challenged aspects of our findings, in part because the commission did not publish the x-rays and photographs underlying the report of the autopsy doctors. These doctors testified before the commission about their examination and the conclusions set forth in their report, but they did not have the images with them when they testified. Warren had earlier decided that the “horrible” photos should not be used by the autopsy doctors because of his earlier commitment to make public any material relied upon by commission witnesses. He believed that the publication of these images was unnecessary and would deeply offend the Kennedy family. Most of us regarded that decision, understandable at the time, as a mistake. The absence of detailed images prompted widespread criticism and debate about the nature of the wounds, the source of the shots, and the validity of the single-bullet theory.

By late May, with the facts accumulating and pointing toward tentative conclusions, Chief Justice Warren wanted to ensure that it was the commission—not the staff—that made the findings to be set forth in its report. Some of our drafts had contained proposed conclusions on issues that the commission’s members had not yet addressed—much to their chagrin. On a day when Rankin was in New York, the chief justice visited with three of us to implement his new approach.

At the beginning of our meeting the Chief Justice read off some 40 or so questions that he had prepared earlier that day. The questions pertained principally to the facts of the assassination and the identification of the assassin, and were quite detailed and appropriate. He asked us what we thought of his approach. We indicated that we thought this would be a useful way for the Commission to consider some of these questions. (Willens journal)

That, of course, is what any lawyer says when the chief justice of the United States has announced a firmly held view. We enlarged Warren’s list to 72 questions, and in late June and early July, the commission decided most of them, leaving several of the most difficult issues, such as evidence of possible conspiracies, for future deliberation.

On September 24, 1964, the commission delivered its report to President Johnson, who released it to the public three days later. Its principal conclusions were as follows:

- Oswald was the sole shooter who fired the bullets that wounded Connally and killed Kennedy on November 22, 1963.

- Ruby killed Oswald on November 24, 1963.

- There was no credible evidence that Oswald was part of a conspiracy.

- There was no credible evidence that Ruby was part of a conspiracy.

- The FBI should have referred Oswald’s name to the Secret Service before Kennedy arrived in Dallas.

- The Secret Service’s policies and practices needed substantial improvement to prevent future assassinations.

We all recognized that evidence might appear in the future regarding possible conspiracies involving Oswald and Ruby but emphasized that no such evidence had been developed during the course of what had been the most extensive criminal investigation ever undertaken in the United States.

At a meeting on April 30, 1964, the commission had unexpectedly decided not to publish, along with the final report, the transcripts of all the witnesses who testified.

Apparently the chief consideration was one of expense and there was not extensive consideration of the policy issues between members of the Commission who discussed the matter. I asked [Rankin] immediately how many of the Commission were present and voted on the issue. He replied that only three were present—the Chief Justice, Mr. Dulles and Mr. McCloy. I indicated to him quite briefly that this was a decision which could not be permitted to stand, and I could see that he felt very much the same way. The Commission members had indicated to Mr. Rankin that they would reverse themselves if the Congressional members of the Commission voted otherwise. (Willens journal)

This crisis was quickly resolved the next day, after Rankin talked to Senator Russell, who assured him that Congress would find the necessary funds. Consequently, the commission in November 1964 published 26 volumes containing transcripts and the exhibits and reports upon which the witnesses relied.

When Warren learned in early 1965 that the National Archives was not processing the unpublished materials of the commission (including agency investigative reports) for release to the public, he complained to the White House. President Johnson promptly directed the National Archives to abandon its normal procedure for handling investigative materials and to start processing the commission’s materials.

Our work has been examined in thousands of books, articles, movies, TV productions, and conferences—with only a few of these supporting our conclusions. What the critics often forget, or ignore, is that since 1964, several government agencies have also looked at aspects of our work. These reviews included a 1968 Department of Justice reexamination of the autopsy materials; the Rockefeller Commission, appointed by President Ford in 1975 to explore various illegal practices by the CIA; congressional investigations in 1975 regarding the FBI’s performance in 1963–64; the Senate’s Church Committee investigation of the CIA and the FBI in 1976; the House Select Committee investigation in 1977–79 of President Kennedy’s assassination; and the work of the Assassination Records Review Board in implementing the JFK Records Act, a law enacted in 1992 that required public disclosure of all assassination-related documents. Vincent Bugliosi’s hefty, exhaustive 2007 book, Reclaiming History, based on 20 years of research, deserves special attention. An accomplished prosecutor for many years, Bugliosi not only examined the assassination and its aftermath but also analyzed (and rejected) multiple conspiracy theories, concluding that no prosecutor could proceed on any of the evidentiary bases for these popular theories.

Looking back on our work, we regret the Warren Commission’s failure to recommend meaningful changes to the policies and practices of the Secret Service. The deficiencies in the Secret Service’s performance, before and during the Dallas motorcade on November 22, 1963, were apparent to all of us. Significantly, several witnesses in Dealey Plaza—but not one Secret Service agent or Dallas policeman—saw a man with a rifle at the sixth-floor window of the depository. The chief justice and other members questioned the adequacy of the agency’s advance planning and challenged the Secret Service’s decision not to discipline the agents who were drinking alcoholic beverages the night before the motorcade—a clear violation of its regulations. Two members of the commission—Allen Dulles and Gerald Ford—argued vigorously over several months that the agency should be moved from the Treasury Department to the Department of Justice. But such a move was strongly opposed by Treasury Secretary C. Douglas Dillon and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover—both formidable and experienced bureaucrats—and it was considered by some commission members to be outside their mission. As a result, no major recommendations were made concerning the operation of the Secret Service. Its continued failures over the decades—the attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan, the consorting with prostitutes in Colombia, repeated violations of the alcohol policy, and recent breaches of White House security—reveal a serious lack of discipline and an inbred culture that will challenge the most aggressive efforts to reform the agency, now housed in the Department of Homeland Security.

Our conclusion that Oswald fired the shots that wounded Connally and killed Kennedy was, and is, firmly based on the available evidence. Oswald owned the rifle found on the sixth floor of the depository, and his palm print was on it. Ballistics experts testified that the bullets that hit the vehicle’s occupants and the three cartridges on the sixth floor came from that rifle. Oswald’s prints were found on several boxes around the window from which he fired the gun. Eyewitnesses saw a man with a rifle at this window. His previous assassination attempt on General Walker, his killing of Dallas patrolman J. D. Tippit (who stopped Oswald for questioning after he fled from the depository), his struggle to resist arrest when he was apprehended, and his many lies during police interrogation all supported the conclusion that he was the assassin. The House Select Committee, using some technology not available at the time of our work, agreed in its 1979 report that Oswald fired the shots that hit Connally and Kennedy. Both Warren and Bugliosi said later that this evidence would have resulted in Oswald’s conviction after a two- or three-day trial had the victim not been the president of the United States.

Contentions over the years that there was a second shooter—most commonly placed on the “grassy knoll”—have proved to be insupportable. The several examinations of the autopsy materials by forensics experts convened by Attorney General Ramsey Clark in 1968, the Rockefeller Commission in 1975, and the House Select Committee in 1977–79 have—without exception—confirmed the findings of the autopsy doctors (and the Warren Commission) that the two shots were fired from above and behind the presidential limousine. This means, of course, that any second shooter would have missed the presidential limousine entirely. But the facts are clear: no other person was seen with a rifle in Dealey Plaza that day; no second rifle, no bullet fragment from any rifle other than Oswald’s, no fourth cartridge—none of these was found anywhere near the assassination site. Notwithstanding this lack of tangible evidence, the House Select Committee (over the dissent of several members) concluded in late 1978 that a policeman’s radio recording contained four sound waves (not shot sounds), determined to have been caused by the three shots fired by Oswald and a fourth shot from the grassy knoll. This hasty and ill-advised conclusion was later found by a National Academy of Sciences committee to be utterly flawed—because the four sound waves occurred some 60 seconds after the assassination.

The elusive search for Oswald’s motive continues to this day. The chief justice did not want the commission to identify any single motive—probably for the simple reason that the members (and staff) had different views on the subject. The commission report listed several factors that may have influenced Oswald’s actions: his inability to establish meaningful relationships with other people, his dissatisfaction with the world around him, his hatred for the United States, his concept of himself as a “great man,” his commitment to Marxism and communism, and his support of the Castro regime. Some of our colleagues, particularly Jim Liebeler, argued strenuously that more weight should be given to the last two of these factors. Some observers have suggested that Oswald’s relationship with Marina may have had a significant influence, emphasizing her rejection on the night before the assassination of his proposal that they look for a place in Dallas where they could live. Bugliosi believed that Oswald, who expressed affection for Kennedy, nonetheless regarded the president as the leading “representative” of the American establishment that he hated. Some historic precedent exists for this view. As Oscar Collazo, one of the two Puerto Ricans who attempted to assassinate President Truman, explained, “Truman was … just a symbol of the system. You don’t attack the man, you attack the system.”

By comparison, there has been very little interest in and no real dispute about Jack Ruby, whose murder of Oswald was seen on television by millions. Ruby thought, with some justification, that he would be considered a hero for ridding the world of President Kennedy’s assassin. Instead, he was convicted and sentenced to death by a Dallas court in March 1964—a decision reversed by a Texas appeals court two years later. Ruby died of cancer in January 1967, a month before the scheduled retrial.

The commission did not uncover any credible evidence—and none has come to light during the past 52 years—that Ruby had conspired with anyone to kill Oswald. The Dallas authorities had announced that Oswald would be transferred to a more secure location on November 24 at 10 A.M. On that Sunday morning, a dancer at one of the strip clubs Ruby owned called him from Fort Worth to complain that his decision to close the club the previous night out of respect for the slain president had cost her $25. Ruby promised to send that amount by money order and left his house shortly before 11 A.M. to do so, his favorite dog in the car. He went to a Western Union office only a few blocks from the Dallas police department and waited in line until he purchased the money order at 11:17, as reflected on his receipt. Walking back to his car, he noticed that a crowd had gathered at the police department and headed over there. Inserting himself in the crowd of reporters and observers, Ruby shot Oswald four minutes later, at 11:21. If Ruby had intended to kill Oswald that Sunday, either on his own or as part of a conspiracy, he would have been at the police department long before 10 to secure the best possible position from which to shoot Oswald. The dog lovers among us were further convinced that he would not have brought his dog along if he had planned to commit murder.

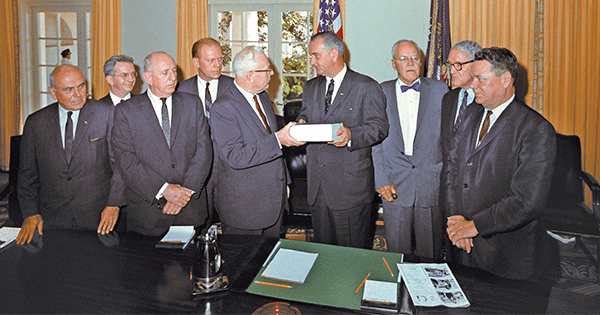

President Johnson receives the finished report from Chief Justice Warren and the commission members. The report went public three days later.

Although we knew that the FBI had originally opposed the creation of the Warren Commission and resented our burdensome investigative requests (J. Edgar Hoover was so angry with the commission’s work that he ordered investigations of commission staff members), we did not believe that the FBI would lie to us. In 1975, however, congressional investigations revealed that Hoover had not testified honestly when he told us in 1964 that the FBI’s investigation of Oswald since his 1962 return from the Soviet Union did not reveal any information requiring the agency to refer his name to the Secret Service before the Dallas trip. In December 1963, Hoover punished 17 agents and officials for conducting an inadequate investigation of Oswald and failing to supply his name to the Secret Service. Another congressional investigation in 1975 determined that Oswald was so offended by an FBI agent’s brief interview of his wife in early November 1963 that he delivered a note a week later (about November 12) threatening to blow up the FBI’s Dallas office or the Dallas police department if the FBI did not stop harassing her. Hoover was not aware of this note, which was destroyed on November 24 at the direction of the head of the Dallas FBI office. If this information had been disclosed to us, it most likely would have resulted in a more critical assessment of the FBI’s performance before the assassination. Of even more importance, it would have provided us with additional, and persuasive, evidence that Oswald acted alone in assassinating the president. It is unimaginable that a person committed to killing the president of the United States would have delivered such a note to the FBI 10 days earlier.

Notwithstanding this evidence, our critics continued to look for a conspiracy to kill President Kennedy—with renewed enthusiasm after congressional disclosures in 1976 that the CIA had been developing plans to assassinate Fidel Castro between the years 1960 and 1963. Disclosure of this information would have enlarged the scope of our investigation—to include a more aggressive examination of Oswald’s contacts with pro-Castro and anti-Castro groups or with persons familiar with such assassination plots. We were offended by the CIA contention, expressed by Director Richard Helms before the Church Committee, that the agency had not been obligated to provide us with information about these secret plots because we had never specifically asked for such information. Helms volunteered that we could have relied on public knowledge that the United States wanted “to get rid of Castro.”

After an extensive investigation, the House Select Committee in 1978–79 concluded that it had found no evidence that the Cuban government, the Soviet government, anti-Castro Cuban groups, organized crime, the CIA, the FBI, or the Secret Service was involved in the assassination of President Kennedy. In light of disclosures regarding the CIA assassination plots directed at Cuba, the select committee undertook a thorough examination of the pertinent CIA files about Oswald, his visit to Mexico seeking a Cuban visa seven weeks before the assassination, and the Cuban government’s knowledge about him. For example, the Mexican government had not permitted us in 1964 to interview Sylvia Duran, the Mexican clerk at the Cuban consulate in Mexico City who had dealt with Oswald. We were required, therefore, to rely on the official Mexican report of her interview by Mexican officials. She later expressed a willingness to testify before the commission, but Warren—mistakenly, we believe—rejected the offer. In 1978, however, Mexican authorities allowed the select committee staff to interview Duran for several hours, during which she provided no significant new information regarding her contacts with Oswald and denied hearing Oswald make any threat against President Kennedy.

On a sunny day in Washington last October, we joined six former Warren Commission colleagues—retired Defense Department historian Alfred Goldberg, retired Ohio judge Burt Griffin, retired New Jersey lawyer Murray Laulicht, Justice Stuart Pollak of the California Court of Appeal, retired law professor David Slawson, and Washington lawyer Sam Stern—to reflect on our investigation and the report we issued. We had been brought together by Todd Kwait, an independent filmmaker who is producing a movie about our work. Our venue was the VFW Building, where we had labored so intensely during those months in 1964.

We recognize that critics will continue to question the commission’s conclusions without regard to the subsequent investigations and the release over the years of virtually all of the government records relating to the Kennedy assassination. Next year, the relatively few documents still withheld at the National Archives will finally be released. Although distrust of government may be embedded in the American political system, we believe that widespread public distrust has grown over the past five decades—with assassinations and urban strife in the 1960s, the Vietnam conflict extending into the 1970s, Watergate and the Nixon resignation, the Iran-Contra conspiracy in the 1980s, and the protracted conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan in the 2000s leading to the present. The inability of our government institutions to function effectively—or even to discuss major issues facing the country constructively without partisan acrimony—also reduces public respect for government. We have lived through this history. Nonetheless, we are proud to have worked on the Warren Commission staff and believe that its conclusions have withstood, and will continue to withstand, the test of time.