Exactly how much does a giant redwood weigh—and why does it matter? Until recently, answering those questions required cutting down the tree to weigh its pieces—a difficult, not to mention destructive, task. Now forest ecologists are jumping on the big-data bandwagon by using terrestrial laser scanning, or TLS, a technique widely used in surveying and geological applications for a decade. Researchers like Mathias Disney, a forest ecologist at University College London, are using lasers to weigh trees to gauge their carbon content.

“If we measure lots of trees, we can start looking for patterns in these data,” Disney says, to answer questions like, “What’s the biggest tree you could possibly have and why?”

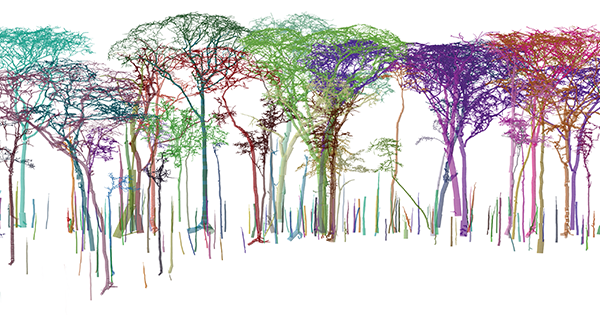

TLS resembles sonar but uses light rather than sound. A camera-like device sends out thousands of pulses of light per second, measures the return time of the light, and converts that time into distance. With enough pulses, scientists can create a “point cloud,” which they transform into a 3-D image of the forest floor. That image provides scientists with the exact measurement of the trees’ volume, which can be converted into mass and weight.

One of Disney’s next projects, in collaboration with NASA, is to digitally weigh the giant redwoods of California—something that’s never been done before. Because a tree is half carbon, knowing its exact mass allows scientists to more accurately determine carbon content and monitor how much carbon is released into the atmosphere when it is burned or decomposes. TLS may also allow a more accurate picture of how transforming a forest filled with giant trees into a forest of relatively small, faster-growing trees will affect the climate, a shift that some scientists predict will occur as the earth warms.

Today, most of the data on global forest carbon dynamics are extrapolated from a few thousand small trees that were cut down and weighed. But comparing trees of different sizes and species growing on different continents “seems to underestimate the amount of carbon there is in tropical forests quite significantly,” says Disney. His research indicates there’s more to be gained from saving tropical rainforests—and more to be lost if they’re destroyed.